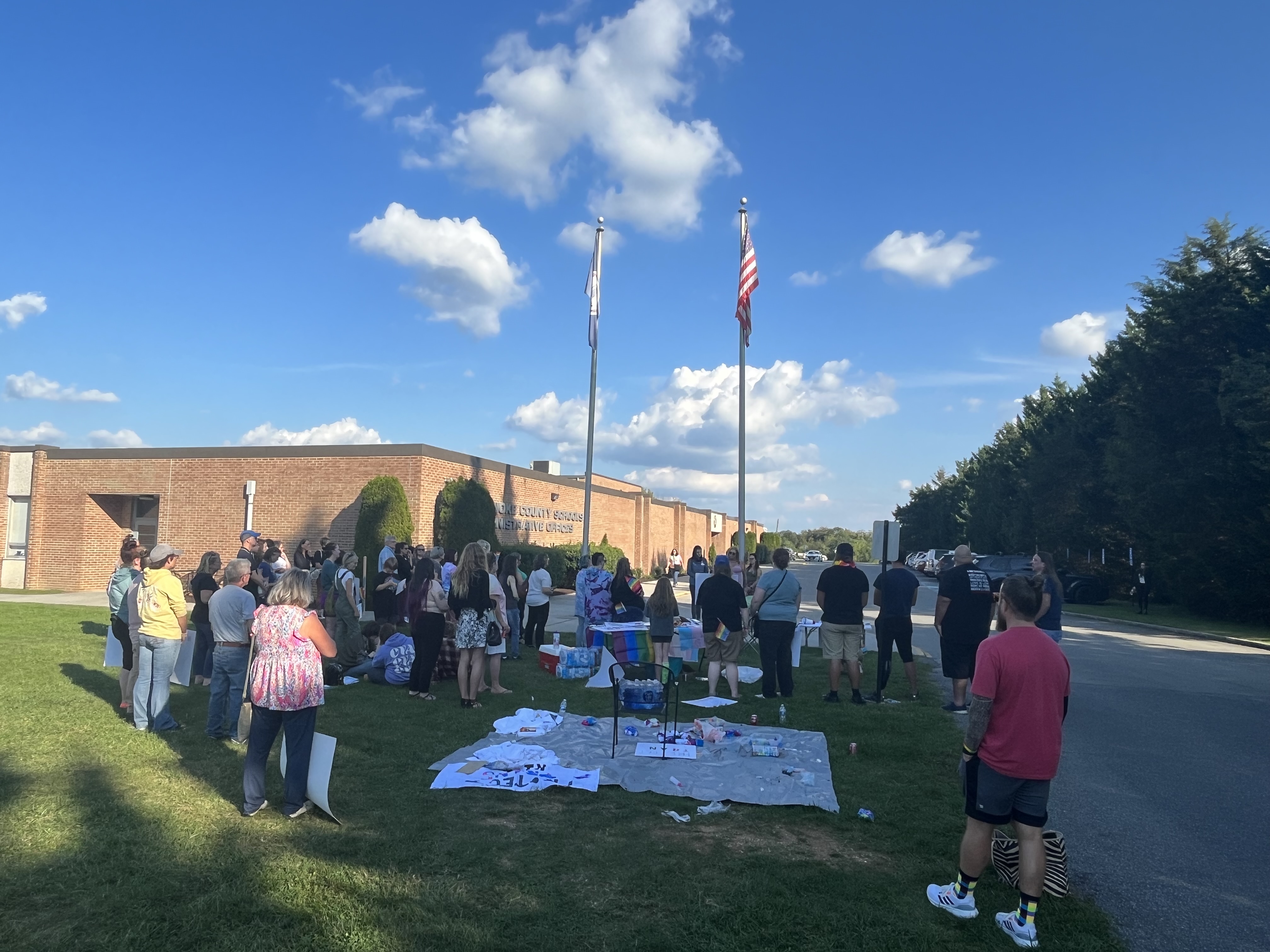

On a sunny Thursday evening in September, about a hundred people gathered on the wide lawn next the central office for Roanoke County Public Schools, some of them arriving hours ahead of the division’s monthly school board meeting.

About two-thirds of the early arrivals had gathered to show support for area transgender students, many holding homemade signs and rainbow flags. A football field’s length away, about 30 members of a local church formed a loose circle to praise the county’s five school board members, who had voted unanimously in August to adopt Gov. Glenn Youngkin’s model policies to limit accommodations for transgender students.

Supporters of the new model policies say it’s a win for parents’ rights; opponents, like the students who gathered with their signs, fear it will foster discrimination of transgender and nonbinary students.

The pastor leading the prayers for the Baptist church group wore a body camera on the lapel of his blazer, mentioning it several times as he stated his desire to avoid an altercation with the other group.

The dueling protests — the pastor with a microphone and portable speaker, the student organizer with a malfunctioning borrowed megaphone — each kept to its own area of the field. The school board meeting that followed that night was also relatively quiet: Although the room was full when it began, it was the first Roanoke County School Board meeting in three months where an audience member wasn’t arrested by officers on the premises for disorderly conduct or trespassing.

In Southwest Virginia and across the state, school boards have operated under the microscope during COVID mitigation and the rise of the parental rights movement.

School board elections are nonpartisan in 41 states, including Virginia, where 89% of school boards are elected. But in some areas, increasing polarization has made it nearly impossible to keep partisan politics off school boards.

The schisms are having effects far beyond hourslong school board meetings. They’re dampening morale in classrooms, teachers say, and in some places, longtime board members who have grown tired of the infighting have opted to not seek reelection.

Tense school board meetings are nothing new, but the attention that’s getting paid to those debates heightened over the past few years as school boards had to focus on COVID issues, said Verjeana McCotter-Jacobs, executive director and CEO of the National School Boards Association.

“The pandemic thrust everybody on high alert around policies in general,” McCotter-Jacobs said, not just regarding public schools. As school divisions made decisions about how to educate children safely during the pandemic, citizens — with their widely varying views on the pandemic’s severity — were paying attention.

That intense level of scrutiny hasn’t let up.

And then add the fact that political polarization has been on the rise for 30 years, said Amanda Wintersieck, associate professor and director of the Institute for Democracy, Pluralism and Community Empowerment at Virginia Commonwealth University. This guide includes select school divisions mentioned in this article. For more information on candidates and races in your area, visit the State Board of Elections. And see Cardinal’s voter guide to learn more about the General Assembly races that will be on the ballot next month. Bedford County Recent issues in the news: School board races: Montgomery County Recent issues in the news: School board races: Pulaski County Recent issues in the news: School board races: In 2019, all five candidates ran unopposed in their districts. This year, four incumbents have challengers and each district has two candidates. Roanoke County Recent issues in the news: School board races: Cardinal’s voter guide to school board races around the region

That polarization has increased primarily on a national level, but it also has trickled down into state legislatures and local governments.

“We used to say all politics are local,” Wintersieck said. “Today we’d say all politics are national.”

Prior to Barack Obama’s presidency, Wintersieck said, Democrats and Republicans looked a lot alike on a national level. But as the range of voices across American government has become more diverse, the two parties have moved further apart from their commonalities at the center. It’s more difficult to have those nonpartisan elections when the sides are closer to the poles, she explained.

The influence of political parties is hard to avoid in some so-called nonpartisan school board campaigns this fall.

In Montgomery County, for instance, two school board candidates, Lindsay Rich for District E and Mark Miear in District B, have been endorsed by the local Republican Party. Facebook “Policy Monday” features by Rich posted in August and September have exclusively discussed how the candidate would support the governor’s trans student policies. Rich and Miear are slated to host an event together at a local coffee shop, with the tagline “We’re not politicians, we’re parents” prominent on the flier.

In neighboring Roanoke County, the local Republican Party has endorsed Shelley Clemons for the open Cave Spring seat and incumbent Brent Hudson in the Catawba District. Both candidates count parental rights among their priorities. Hudson, who currently serves as board chair, is being challenged by Samantha Newell, a parent who launched a write-in campaign in August. Newell spoke at the student-led rally before the September school board meeting, and during public comment at several school board meetings over the summer, in support of LGBTQ+ students.

And as partisan politics come into play for school board elections, Wintersieck said one likely outcome is that more extreme candidates on either side of the aisle will run for — and win — elections.

One group backing some of those candidates is Moms for Liberty, a group that launched during the pandemic under the banner of parents’ rights and has espoused anti-LGBTQ+ and anti-diversity and inclusion rhetoric. Candidates endorsed by the group won 275 of the 500 races the organization promoted in 2022. Eventually, Moms for Liberty wants its chapters to serve as “watchdogs” for all 13,000 school districts across the country.

The Moms for Liberty chapter in Bedford County has already begun to gain influence on that school board. Last fall, Chris Daniels won a special election to finish the final year of a term in District 7, which was open due to a resignation. He listed parental involvement in children’s education as his primary issue, followed by a need to “get back to the fundamentals” of education, and he touted endorsements from the Bedford County GOP and the local chapter of Moms for Liberty. Tiffany Justice, one of the cofounders of Moms for Liberty, visited the county during early voting last November.

Daniels won with nearly 53% of the vote. In his first year on the board, Daniels was one of two members who pushed to update Bedford County’s policy for “teaching about controversial issues.” The policy update approved in June after several months of debate prohibits teachers from initiating discussions with students about sexual orientation or gender identity.

Daniels has been endorsed again by both groups as he runs this fall for a full term.

In Montgomery County, the Moms for Liberty chapter that launched earlier this year endorsed Miear, the former superintendent, in his race against Penny Franklin. Longtime incumbent Franklin was on the board when it made the unanimous call to fire Miear in 2022 after he allegedly shouted at a county schools employee for 45 minutes because he felt the county’s trans student policy violated his own rights as a parent. Miear is running on a “back to basics” platform focusing on academic achievement.

“The candidate must support parental rights,” said chair Ginny Perfater of the chapter’s criteria for endorsement. “After speaking with Mark, we believe his values align with ours.”

She said the decision among the group’s “roughly 20” members to endorse him was unanimous.

Polarization can lead to whiplash for school divisions

Education used to be an issue where almost everyone agreed on one key point: that children deserve high-quality public education, Wintersieck said. But in some places, it’s no longer easy to identify basic common ground among candidates. “The tone of the conversation has changed,” she said.

The issues being debated at these public meetings have become more visceral, Wintersieck said. They reveal not only what people think about the U.S. public education system, but also what they think about at the core of human identity.

“The guardrails have come off democracy in the way we discuss these issues, in what we put forward as facts,” Wintersieck said.

Kimberly Irvin, a special education teacher at Hidden Valley High School in Roanoke County, said she had never gotten up to speak in public before the May board meeting that split the community in two. At that May meeting, local parent and real estate agent Damon Gettier talked for nearly a minute and a half over the allotted three minutes per speaker, calling out four staffers by position who he claimed were “bent on indoctrinating our children on LGBTQA and not reading, writing and arithmetic.”

In response, the board passed a policy that said teachers can’t display classroom decor that promotes any political, socio-political or religious beliefs.

Gettier didn’t use names, but Irvin could tell who he was talking about. One of the people he called out for being a so-called groomer particularly shocked Irvin. “I was listening to my colleague, and a teacher my children adore, being openly abused verbally,” Irvin said. “And the people who employed this person, who should have protected them, didn’t step in. And that was the final straw for me,” she said. She’s spoken at almost every board meeting since, making a point to say that her views are her own as a parent and educator.

Irvin initially feared retaliation for her statements in support of LGBTQ+ students and teachers, but she says she hasn’t experienced any — though she was one of three teachers in her school recently asked to remove small rainbow decorations from personal property the day before a visit by a school board member. The teachers complied but are waiting for clarification from the administrator about whether they’ll be able to display the decorations again.

Irvin said she’s so fearful for the future of the Roanoke County School Board that for the first time, she’s volunteering for a political campaign. She’s backing Mary Wilson, who’s running for the open seat against Republican-backed Shelley Clemons.

And she said that she and her husband have discussed whether it could make sense to leave the school district where she works and her children attend if the school board continues to increase its conservative seats. “I could homeschool, but it’s not what I want to do or what I want for [my kids],” she said. “They love their school and I love teaching at my school.”

Meanwhile, she said discussion among teachers in the division who have considered leaving has escalated. “It used to be the county was the coveted teaching position.” Now, her colleagues are thinking about looking for work in Roanoke or Salem. Both neighboring divisions offer higher pay, she said. And both of them have school boards appointed by the city council.

The impact of school board members with viewpoints on far ends of the spectrum on the classroom climate for teachers may become more evident in the coming years.

Starting after the 2021-2022 school year, the Virginia Department of Education began collecting data from school divisions about why teachers and administrators chose to leave.

Only 63 of the more than 1,700 teachers who left their positions in summer 2022 said that “outside pressure from parents, community, social media” was among the top three reasons for their departure. Three of those 63 teachers had worked in Bedford County, where Moms for Liberty has an active presence.

Statewide data for the 2022-2023 school year isn’t yet available. Roanoke County shared the data it sent to the state this summer, which showed only one instance of a teacher leaving the division due in part to outside pressure; most of the 115 teachers who left reported that they took a job in another public school division or chose as their reason “family/personal considerations.”

Nor are top administrators immune to anxiety that can come from board politics.

In Radford, attendees packed the board room and overflow area in June for the last meeting with Superintendent Robert Graham, who had suddenly announced his resignation amid rumors that new conservative board members had forced him out. The livestream of the nearly four-hour meeting, which shows Graham holding back tears while receiving a standing ovation from the school board and the crowd, has more than 4,000 views on YouTube.

Two of the three new members elected to the board in fall 2022, Gloria Boyd and Chris Calfee, were endorsed by the Radford Republican Committee. Their influence was evident as soon as they attended their first board meeting, said Graham, who had been superintendent for eight years. Suddenly, several board members wanted to be involved in the day-to-day operations of the school division, which took up a lot of Graham’s time and energy, he said.

“The number one job [of a school board member] is policies and procedures,” he said, not day-to-day operations.

It took less than six months for Graham to resign, for what he has described as board member micromanagement of himself and of other teachers and administrators. As the relationship between Graham and the board soured and monthly meetings grew more tense, Graham said it became a distraction to what really mattered: focusing on the city’s children.

Graham, who was immediately hired as superintendent in neighboring Pulaski County, said some candidates who run for school board seats might be surprised by the duties involved. But if new board members are trying to push an agenda, the regular duties of the school board won’t really support that, Graham said.

In an interview with The Roanoke Times in June, Boyd, a retired teacher, said that the current board has worked within its authority but wouldn’t automatically approve policy proposals “without asking questions.”

School board Chair Jenny Riffe did not respond to an email request for comment for this story.

The turnover of school board members during election years is something superintendents worry about, Graham said. Administrators may know their current board members’ expectations and priorities, but “you don’t know what’s coming” once that board changes, he said. If administrators have to change their methods to meet dramatically different board expectations, for better or for worse, it’s likely there will be similar disruptions for teachers in the classroom as well.

McCotter-Jacobs of the National School Boards Association said a major challenge for modern school boards is centering conversations “around the best interests of children within the context of community.” Every community is different, which is why local decision-making is so important, she said. But those big decisions that often have ties to local finances come with a lot of responsibility.

“A single-issue candidate is going to learn really quick and realize there’s so much to be held accountable for,” she said.

Attendance at Radford School Board meetings has died down for now. No board seats are up for election this fall. But the battle lines have been drawn between liberal residents, some of whom are organizing a recall effort to try to remove the board’s conservative members, and more conservative residents who have largely been quiet at recent meetings.

In Pulaski County, Graham could find himself working with another divided board.

When the last board was elected in 2019, most candidates were incumbents and each ran unopposed. This year, each district’s race has two candidates, and the local Republican Party has endorsed a candidate in each one.

Social media makes campaigning easier for a job that’s always been hard

It’s easier to keep up with local school boards than ever before.

Many school divisions started livestreaming meetings during the pandemic, and school board members and candidates often operate Facebook pages to promote their work to constituents. That helps candidates reach voters at home on their devices. But it has also turned up the volume on the feedback that candidates and school board members get from the public.

In 2022, a public commenter at a Montgomery County School Board meeting showed Facebook photos of school board chair Sue Kass not wearing a mask indoors, which the speaker said was hypocritical of the county policy.

Kass, who said the photos were taken in a private setting with her “COVID pod,” stormed out of the meeting as the speaker, Alecia Vaught, warned, “We’re coming for your seats.”

Vaught, who runs an organization based in Christiansburg called Second Monday Constitution Group, repeated the statement during a segment on the Fox & Friends program on Fox News a few days later, saying, “We’re getting these liberals off of our school board.”

“I got death threats, thousands of emails, my husband and kids were threatened,” Kass said, after Vaught’s speech and her own reaction went viral.

She said politics hadn’t been a factor in her race for a school board seat in 2019. Up until that point, the former county teacher said the primary division on the school board had been over school funding and equal treatment of schools in the Blacksburg area, which has four seats on the board, versus the Christiansburg area, which has three.

Now, she said, it’s a battle of political parties. “COVID was the shift,” she said. “COVID exacerbated everything. It brought out the worst in everyone.”

The intensity of the political division in the school district has led to infighting on the school board, leaving the entire body frustrated and unable to focus, she said. Kass is finishing her four-year term on the board this fall. She’s not running again, partly because of demands at her day job, but also because she couldn’t fathom putting her family through another four years of it.

Years ago, the only way to get that kind of access to a school board member was to attend the often hourslong meetings in person.

Jerry Canada, who spent 25 years on the Roanoke County School Board representing the Hollins District, can recall when there wasn’t a time limit for speakers during public comment, causing some meetings to last until close to midnight.

“We almost never talked about politics. No one cared which way you leaned,” he said. “We never lost control.” But he admitted it’s a tough job to be on a school board — and it always has been.

When the board of supervisors changed the school board from appointed to elected in the mid-1990s, Canada decided he’d run to maintain his seat. He was never opposed in any of his reelection years until he chose not to run again in 2017.

In 2021, Canada ran again but lost to current board member David Linden. Canada said he found it difficult to come up with a clear platform. He knew it was hard to promise anything to voters, he said, when a three-person majority would be required to pass on the five-person board. “You can’t do anything unless you get two other people to agree with you,” he said.

Two new statewide groups have sprung up this year to support school board candidates and members. Both claim to be nonpartisan, but the School Board Member Alliance based in Forest is right-leaning, while the We the People for Education in Richmond leans left.

The School Board Member Alliance focuses on providing training about what school board members can do, rather than focusing on what they can’t, according to its website. It supports parental rights and educational freedom while encouraging discourse among school board members. That mission echoes a complaint held by some school board members that the Virginia School Boards Association, which was up until now the standard for guidance in the state and represented all school boards, is too liberal.

(The Virginia School Boards Association offers training and policy guidance along with limited legal consulting for member school divisions but is not a member of the National School Boards Association. It withdrew from the national association in 2022 after raising questions about that group’s governance.)

Cheryl Facciani, a member of the Roanoke County School Board, and Chris Daniels from the Bedford County School Board are directors for the School Board Member Alliance, which lists parents’ rights as one of its key priorities.

We the People for Education, meanwhile, lists “pushing back against political extremism” among its goals. Anne Holton, former Virginia secretary of education and current Virginia Board of Education member, is an advisory board member.

Either of these groups could win the loyalty of school board candidates or members who want to do things differently than in the past. In September, the Warren County School Board voted 4-1 to withdraw its VSBA membership, saying the association didn’t represent the interests of the school division.

These statewide groups have the potential to serve as proxies for political parties for school board hopefuls seeking to keep an appearance of nonpartisanship during election season. Others may prefer to have their name aligned with the local Democratic or Republican party to aid their name recognition when voters head to the polls.

With the new classroom decor and trans model policies now firmly in place in Roanoke County schools, it’s hard to tell when the crowds will subside. November election results could calm the discourse, or further stoke public disagreement.

All that’s truly clear for school board meetings throughout the region is that there’s a new normal for what qualifies as “business as usual.”