Take a whiff on me, that ain’t no rose

Roll up your window and hold your nose

You don’t have to look and you don’t have to see

‘Cause you can feel it in your olfactory

— Loudon Wainwright III, “Dead Skunk”

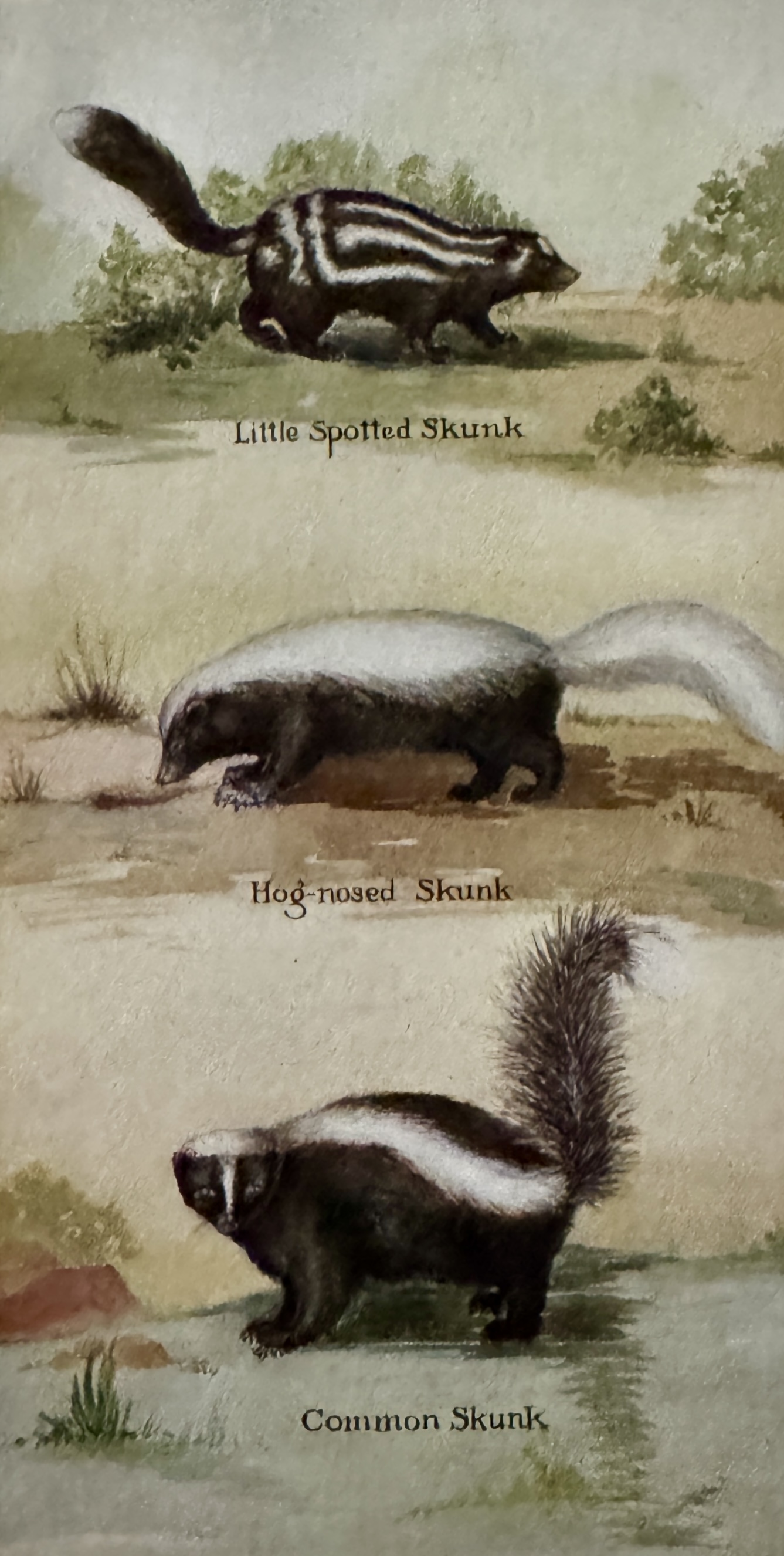

In theory, I like skunks. They’re cute little critters, distinctive, black with white stripes, and their fur is like an animal tuxedo. They never bother humans unless they are irritated, afraid, or dead. They have few natural predators due to “the unique weapon of defense possessed by Skunks and which once experienced will never be forgotten,” wrote H.E. Anthony in his Field Book of North American Mammals.

Unfortunately, I have had multiple encounters with them when they are irritated, afraid, or dead. I was reminded of this recently when, in the spirit of the season, I removed a dead one from a street in our neighborhood. It was at least my fifth attempt at skunk wrangling and/or damage control.

The scientific name for the common striped skunk is Mephitis mephitis. “Mephitis” is the Latin word for a foul odor coming from the earth. It was also the name of a minor pre-Roman goddess worshipped from the 7th century BC to the 2nd century AD and associated with the Aosta Valley in Northern Italy which, according to the poet Virgil, featured a swampy marsh that was the entrance to Hell. In modern times, this foamy marsh emits what one source claims is the highest CO2 emission rate ever measured on Earth. (The region is better known today for cheese, fondue and old manor houses.)

My dad and uncles mostly called Mephitis mephitis “polecats,” although a polecat is another critter altogether, like a weasel, native to Europe. The confusion dates to at least 1694, when John Clayton, an English naturalist, published a report on his trip to the Royal Colony of Virginia in the journal of the Royal Society of London, noting, “There are (in Virginia) several sorts of Wild Cats, and Poll-Cats.” (Much of his fascinating account of Virginia domestic and wild animals seems accurate, although he also believed raccoons were a type of monkey.)

The word “skunk” for the North American animal comes from an American Indian word “segankw,” according to the Oxford English Dictionary. The first reference in English to skunks is from 1634: “The beasts of offence be Squunckes, Ferrets, Foxes.” An 1831 reference noted that in New England, “skunked” was slang for failure to get a king in a game of checkers. My favorite reference is from Washington Irving in 1835, who wrote, “He was advised to wear the scalp of the skunk as the only trophy of his prowess.”

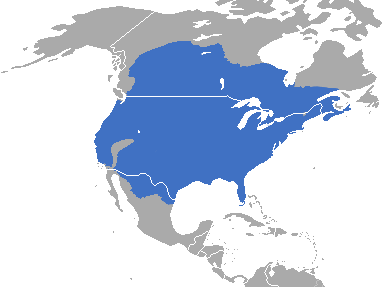

The common striped skunk still gets little respect, unlike its rarer, more reclusive cousin, the eastern spotted skunk (Spilogale putris — “stinking spotted weasel”). Spotted skunks live in the Virginia mountains and Blue Ridge foothills, as well as other states, but I’ve never seen one. Their numbers have been declining since the 1940s, according to the state Department of Wildlife Resources, which devotes an entire section to them on its website, including a photo of one standing upright on its front legs with tail in the air preparing to spray. Spotted skunks have been studied extensively by the Eastern Spotted Skunk Collaborative. A Virginia Tech researcher wrote her dissertation on them. Researchers with the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency have nicknamed some spotted skunks (Rowdy, Squirt), which they are tracking via radio collars.

So much for the fancy spotted skunks with cute nicknames doing handstands. This story is about the anonymous common striped skunks. Like everyone who grew up in rural Virginia, I am accustomed to their scent as long as it comes in small doses. It suggests the odor of strong, hot coffee. A gentle waft of skunk smell on the highway is a pleasant reminder of coming home from my grandmother’s house at night when I was a child.

But a close encounter with a dead skunk, as Loudon Wainwright III sang, is nothing less than repulsive. Such was the case recently when I passed a couple of black vultures dissecting a dead skunk in our suburban neighborhood in Lynchburg. The scent was so strong it lingered in my truck for at least 24 hours, and I assumed the skunk itself would be handled by some omniscient dead animal remover. Our neighborhood is a bit hidden in a semi-wooded area between Timberlake and Leesville roads, and I guess no one called the city, so that didn’t happen.

Two days later, we passed the deceased skunk again on the way home from Christmas shopping. By now it was in the middle of the street, but still reeked: time for direct action. I went home, got a shovel, and scooped up the carcass. Closer examination revealed the buzzards had managed to turn the poor little mammal inside out, leaving the pelt and I assume the twin scent glands in its rear end intact. I tossed it over into the woods but noticed a wet streak on the shovel, apparently pure skunk spray. I washed the shovel with water, rubbed it in dirt and dead leaves, and leaned it against a pine tree in the far corner of our back yard not too from where our late cat, Tom Stinnett, is buried.

Tom was a long-lived, pampered, indoor cat but he was not the smartest creature when it came to anything other than sleeping, eating or cozying up with us. Even though they were separated by a screen door, Tom managed to tangle with a skunk one summer evening. I heard him hissing and meow-growling, went to investigate and found him with all his fur on end and his tail poofed out. I picked him up, his fur was wet, I wondered how that happened, and a split-second later realized that a skunk had sprayed poor Tom through the screen. Pretty awful. I eventually got the scent off my hands, but Tom was another matter. We doused him in skunk odor remover and the scent got better but lingered for many months, apparently emerging from the layer of fat under his skin on hot days or if he became agitated.

You’d think we live in a wildlife refuge instead of a subdivision within the city limits. A nearly tame herd of deer roams the woods and backyards. If all the pecans squirrels buried in our yard sprout, we’ll be living in a forest ourselves. We have pileated woodpeckers, groundhogs, the occasional coyote, and this summer I saw a beautiful golden fox lope across the yard, pursued by crows. That followed the departure of two Cooper’s hawks who marauded around the area for a couple of weeks. While I was writing this, a small bird tried to nest in some of our outdoor Christmas greenery, and three bluebirds refreshed themselves from the icy bird bath. I love all the wildlife, but not too long after we moved here in the 1980s, a family of skunks joined the menagerie. We had young children, as well as two indoor/outdoor cats, and I wanted the skunks gone. I’m not proud of this, but I bought a BB gun, began zinging the skunks on their rumps for a week or two, and they disappeared. At some point after that, I noticed skunk smell coming from a window well at the back of the house. Turns out it was coming from a baby skunk — aka a “kit.” Kits can spray at eight days old, but I felt sorry for it and propped an old board and some sticks in the window well so it could climb out. Alas, it was dead by the next morning. I formed a window-well cover out of chicken wire held in place with tent stakes to avert future tragedies, and again the skunks seemed to vanish for a while.

I blame the squirrels for the next skunk incident. We’d learned to tolerate the squirrels swinging from the bird feeders, dashing under our cars, sharpening their teeth on the deck boards and digging up plants while burying and retrieving nuts. We generally enjoyed watching their antics but were not amused when Ellen’s car refused to start and all the dashboard lights began flashing. I finally got it running, and we drove it, slowly, to the dealership in Roanoke, which called the next day with bad news. A “rodent” apparently had chewed a small hole in the evaporation line from the gas tank. I’m no mechanic but the “evap” line is so important that the car’s sensors go nuts if there’s a problem or loss of pressure. And, as with all modern cars, many parts are connected, so we had to get a new gas tank as well. Further research revealed that some of the line insulation in modern cars contains recycled peanut hulls. Squirrels love peanuts, so I convicted the squirrels and sentenced them to banishment. I bought a humane squirrel trap, a flat wire cage marketed to catch only squirrels, not skunks, and baited it with peanuts, catching several squirrels which I relocated to some family land we own out in the country. (Not proud of this either, because relocation of wild animals can disorient and confuse them to the point that they don’t survive, but after this latest escalation by the squirrels we were on a wartime footing.)

One morning I went out to check the supposedly skunk-proof trap and found not a squirrel but an enraged skunk. Grabbing a rake, I tried to open the trap from a few feet away and we made eye contact. Big mistake: He ceased jumping around and instead began to watch me, raising his tail, getting ready to spray. I retreated to the house, got an old beach towel, and tossed it over the trap. He immediately let loose, soaking the grass and the towel which then contaminated my Crocs and old blue jeans. I figured that skunks need time to “reload” after their initial blast, so I hooked the rake into the cage, dragged it to the truck with the skunk inside, and covered it with an old blanket. I’ve since read that skunks can squirt multiple times but he had either used up his liquid ammo or lost interest in me, so no further spray. I also relocated him to our farm where I had a difficult time convincing him to leave the cage, but he eventually jumped out and ran off.

H.E. Anthony, who I quoted in the first paragraph, was curator of the Department of Mammals at the American Museum of Natural History nearly 100 years ago. He mentions that after their scent glands are removed, skunks could become playful pets, and noted that they could be caught in the wild if their tail was held down first. However, he added, “My own experience is that the element of of risk is so great, and the likelihood of some part of the scheme not developing (as planned), that I would class (this) as impractical for the layman.” No kidding.

Despite all this, I still like skunks and have a small stuffed-animal skunk I bought at a state park in my basement office. I just examined it and found it was made in Indonesia. Indonesia doesn’t have any Mephitis mephitis, but they do have stink badgers. Scientists reclassified them in the 1990s as skunks, not badgers, and they resemble skunks, so what can I say except welcome to the party. I haven’t been sprayed yet.

Stinnett is retired editor of The News & Advance and The Roanoke Times. He is a member of the Cardinal News Journalism Advisory Committee and lives in Lynchburg.