This is the second of a three-part series of stories written by students at Cumberland Middle School, who have researched and sponsored an historical markers related to the history of the Lucyville community.

Part 1 looked at the origin of the community and Scholar Athlete, Theodore T. Coleman.

Part 2 details the life of family of Shed Dungee, whose descendants included the first African American elected to the South Carolina state legislature in the 20th century and later the first African American state Supreme Court justice in that state. He eventually became chief justice.

Today is part 3. It was written collaboratively written by the 4th Block, U.S. History II class of Cumberland Middle School: Marlie Alvarez, Salonna Robertson, Jaleel Palmore, Mikayla Walton, William Trevillian, Coahen Trussell and Trevor Hurtt (Cody Maxey not pictured).

Last school year, the National Education Association Foundation awarded a grant to Cumberland Middle School to fund a Virginia Historical Roadside Marker. Seventh grade students in Power-Up (Enrichment Class) conducted research, completed primary source activities, collaboratively wrote the marker text, and fact checked the proposed Lucyville Historic Marker text with primary sources. It resulted in the seventh grade U.S. History II students’ successful application for the “Lucyville” Community. On June 15, 2023, the Virginia Department of Historic Resources formally approved the following historic marker text and location.

Sponsor: Cumberland Middle School

Locality: Cumberland County, VA

Proposed Location: Trents Mill Road (Route 622) at the intersection with Oak Hill Road

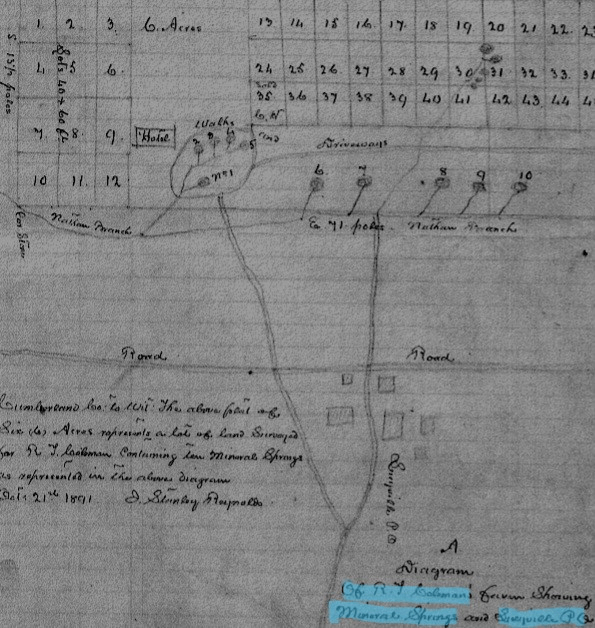

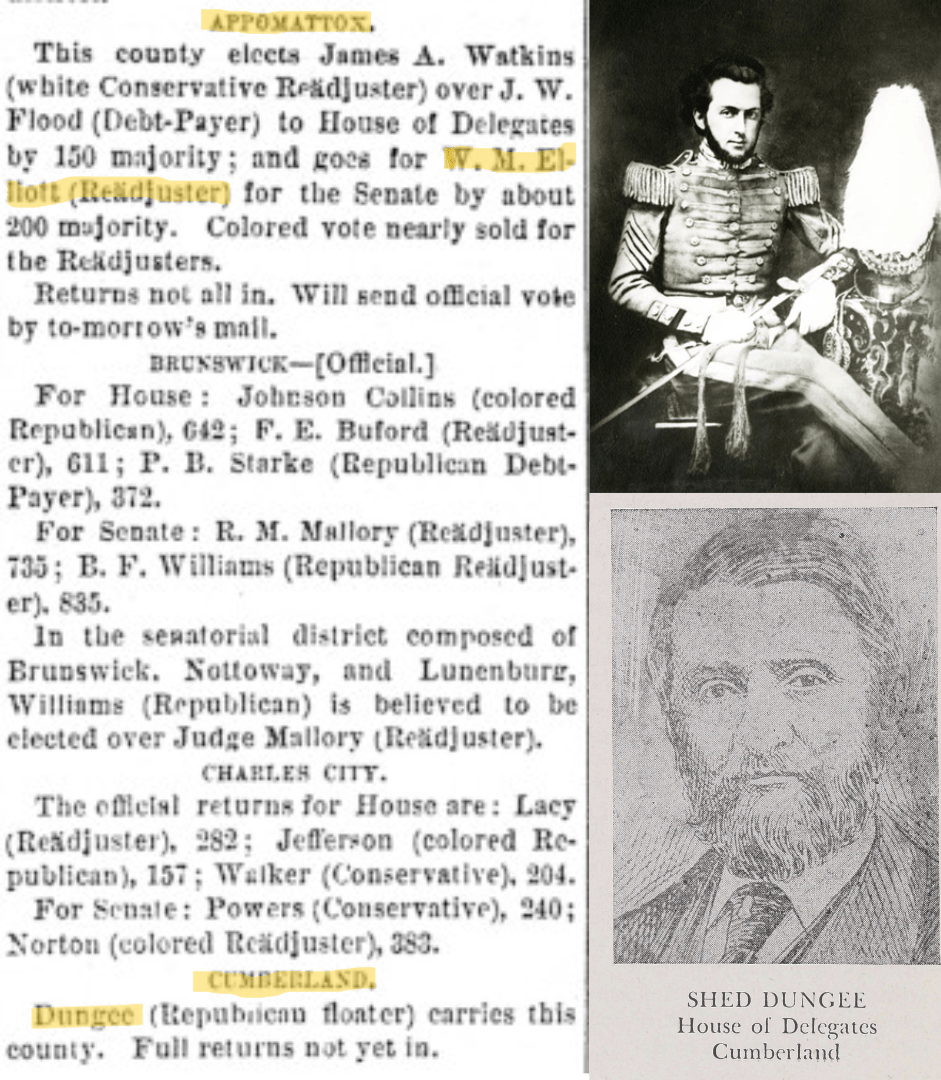

The Rev. Reuben T. Coleman, enslaved at birth, became an entrepreneur after the Civil War. About 1.5 miles north of here he established Lucyville, named for his daughter, which in the 1890s featured a bank, post office, newspaper, and mineral springs resort that drew visitors from afar. Coleman, who challenged segregation, was the pastor of Mount Olive Baptist Church and a local Republican leader and officeholder. His brother-in-law Shed Dungee, formerly enslaved, represented the area in the House of Delegates (1879-1882) and aligned with the Readjusters, a biracial coalition that achieved major reforms and supported public education. Many Lucyville residents left during the Great Migration.

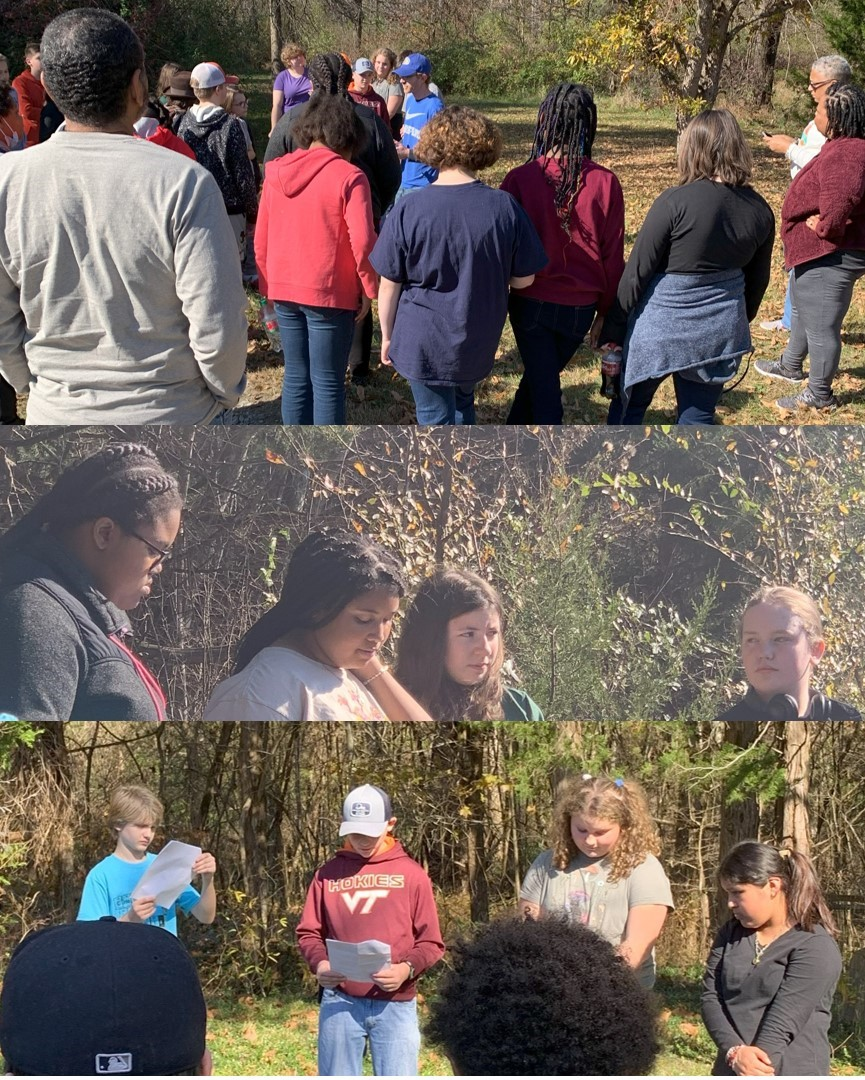

This school year, current seventh and eighth grade students are speaking at field trips and planning the Lucyville Historical Marker unveiling.

The following portion of the article is a summary of the third Story Map of the series, titled “James M. Hendrick Sr., the Confederate veteran laid to rest on Rev. Reuben T. Coleman’s property” is collaboratively written by (pictured from left to right) Marlie Alvarez, Salonna Robertson, Jaleel Palmore, Mikayla Walton, William Trevillian, Coahen Trussell and Trevor Hurtt (Cody Maxey not pictured).

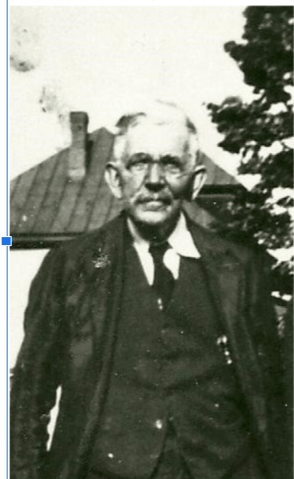

Pvt. James M. Hendrick Sr.

The Confederate veteran laid to rest on Rev. R.T. Coleman’s property.

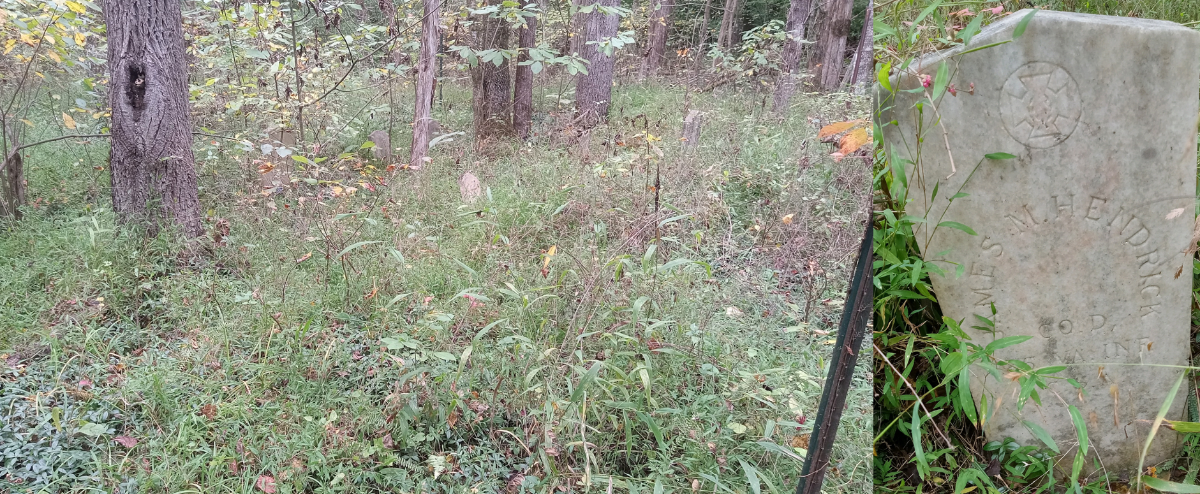

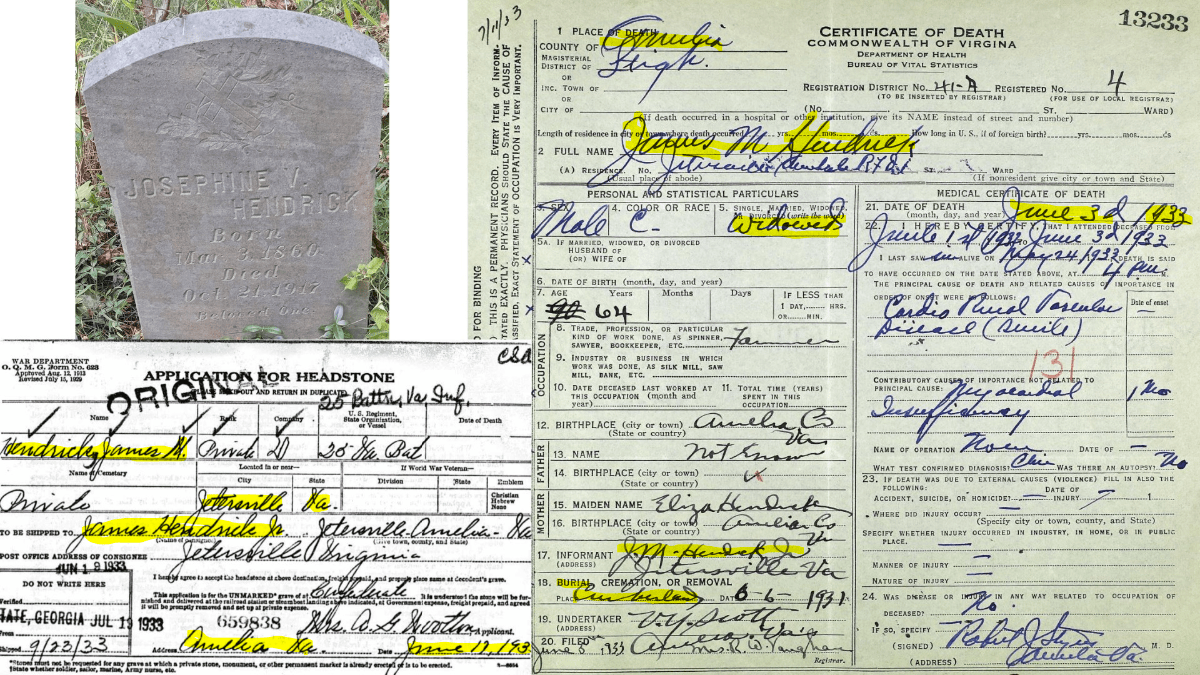

James M. Hendrick Sr., and his second wife, Josephine Whitlow Hendrick, are buried near the ruins of Reuben T. Coleman’s house and the former site of the Lucyville Post Office.

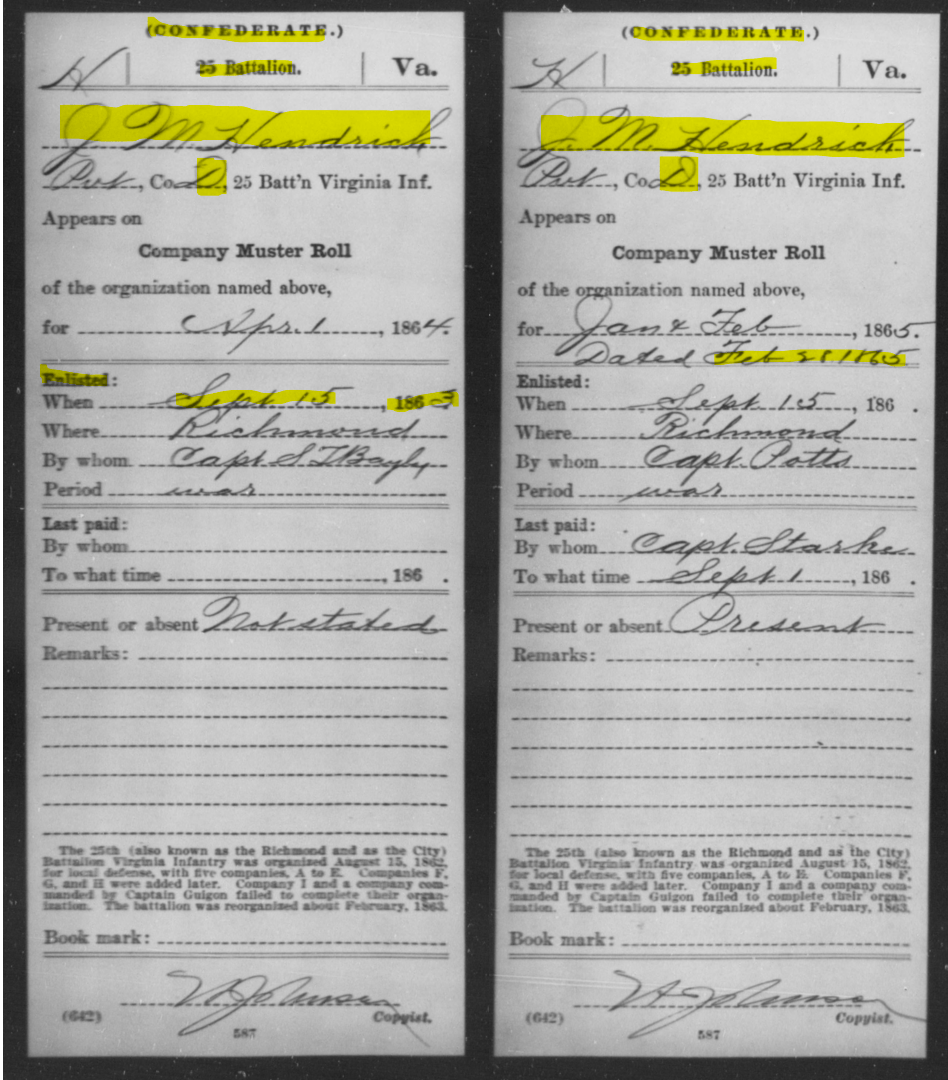

During the Civil War, Pvt. James M. Hendrick served in the 25th Virginia infantry “City Battalion,” Company D. It was established in Richmond on August 15, 1862, and Wyatt M. Elliot was the commander. James M. Hendrick Sr., enlisted on September 15, 1863. He remained with the “City Battalion” after February 28, 1865.

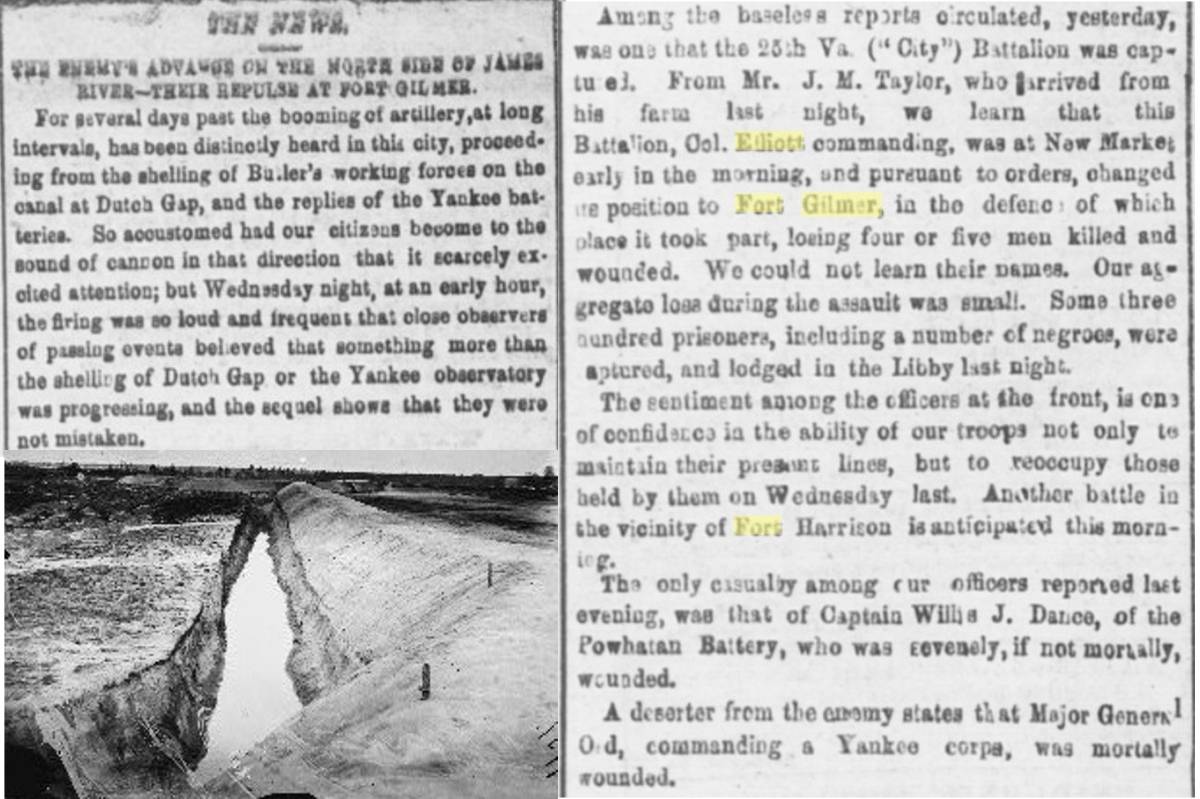

The 25th Virginia infantry, “City Battalion,” were active during the Petersburg Siege. On September 29, 1864, they defended Ft. Gilmer at the Battle of New Market Heights. The Union won the battle of New Market Heights but could not take Fort Gilmer. The Union also had the highest casualties with 4,150.

Many of the casualties came from African American units. Fourteen African American soldiers from the USCT received the medal of honor for their bravery.

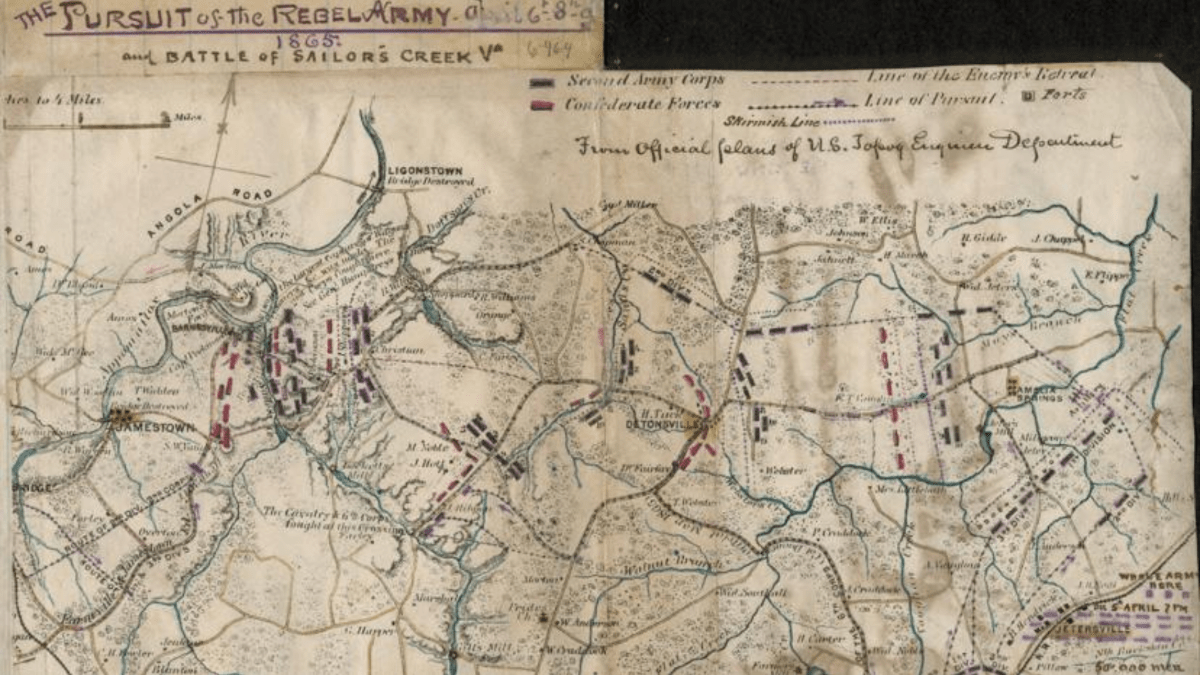

There is no record of James M. Hendrick Sr. being captured in battle or paroled at the end of the war. The commander of his unit, Wyatt M. Elliot, was one of 7,700 Confederates captured on April 6, 1865, at the battle of Sailor’s Creek. The Battle of Sailor’s Creek was fought in the area where the Hendricks lived. General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army surrendered to the Union on April 9, 1865.

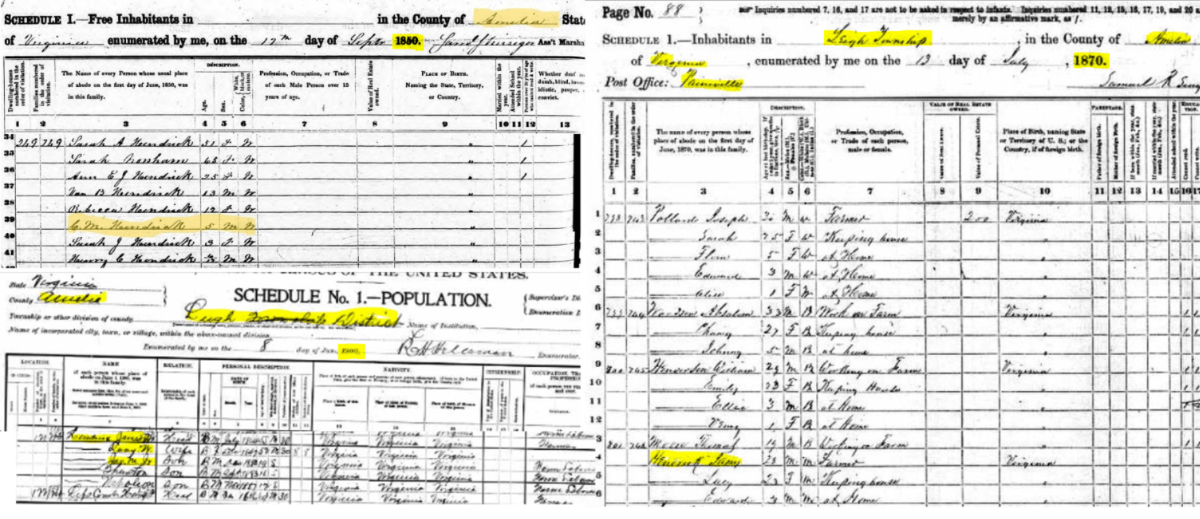

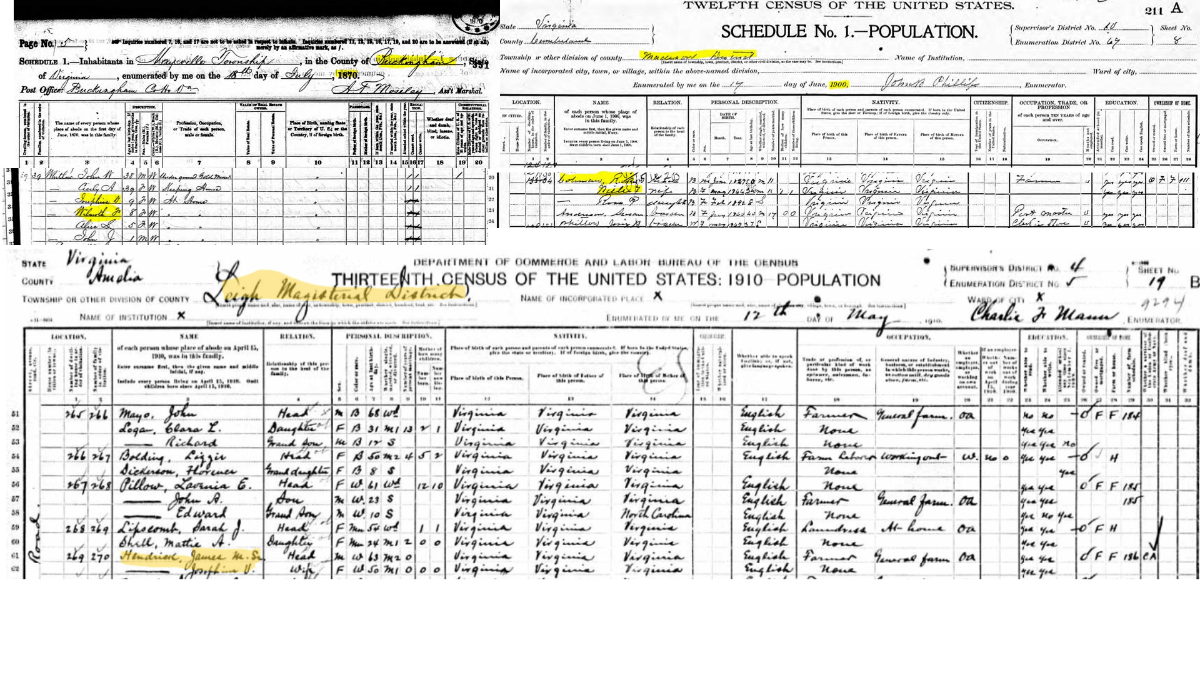

James M. Hendrick was first listed as a child in the 1850 census living in Amelia County. After the Civil War, the 1870 Census lists he and his wife Lucy, living in Amelia County, having both White and African American ancestry. In 1900, he and his family continued to live in Amelia County and were listed as African American.

James M. Hendrick’s first wife, Lucy Hendrick, passed away after the 1900 Census. After her death, he married Josephine Whitlow. Josephine Whitlow’s sister, Willie Whitlow, was married to Reuben T. Coleman. The 1910 Census listed James M. Hendrick and Josephine Hendrick as White living in Amelia County.

Rueben T. Coleman passed away in 1909 and was buried near his home. After his death, his wife, Willie Whitlow Coleman, continued to live in the area with her daughter, Rosa Pearl Coleman Lipscomb, and son-in-law Warren H. Lipscomb. Willie Whitlow Coleman’s sister, Josephine V. Whitlow Hendrick, died in 1917 and was buried in a small family cemetery behind R.T. Coleman’s home. In 1933, Pvt. James M. Hendrick passed away and was laid to rest beside his wife.

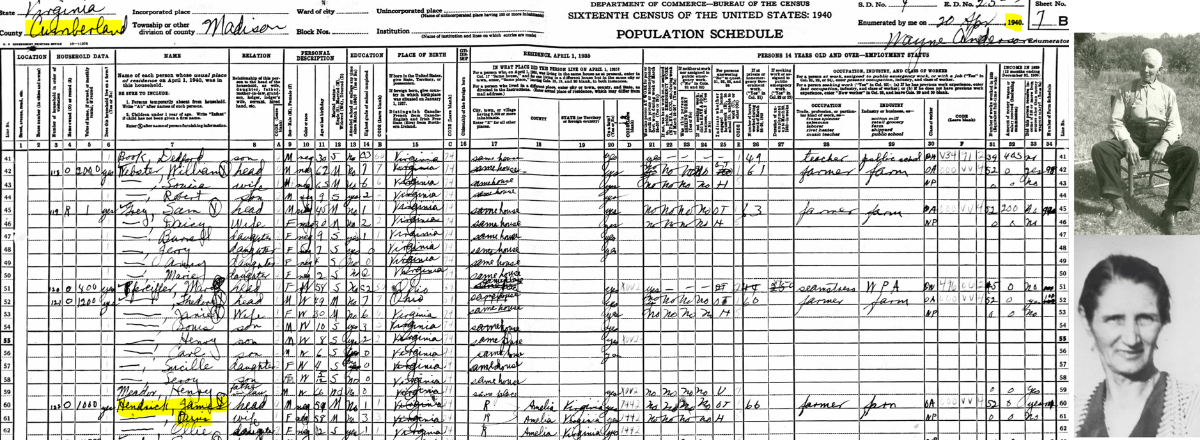

James M. Hendrick Jr. and his wife, Parrie Lee Robinson Hendrick, moved from Amelia County after the 1930 census. They moved into a home on Trent’s Mill Road in Cumberland County. Her father, J. Henry Robinson, was the second pastor of Mt. Olive Baptist Church, and her grandfather, John Lipscomb Robinson, represented Cumberland County in the Virginia Senate during Reconstruction.

After the Civil War, Wyatt M. Elliott was a publisher of the Richmond Whig and represented Appomattox County in the Virginia Senate. He was a member of the Conservative (Democratic) Party before joining the Readjuster Party. This biracial political coalition was led by William Mahone, a former Confederate General. The Readjusters wanted to fund public education by not paying the state debt in full. Appomattox County also elected James A. Watkins as a “Conservative Readjuster” to the House of Delegates. He was later criminally charged with accepting a bribe in exchange for a political appointment and left Virginia because he did not want to face criminal charges. Lucyville’s Shed Dungee, a member of the House of Delegates, was also in the Readjuster Party. He was a Republican before becoming a Readjuster.

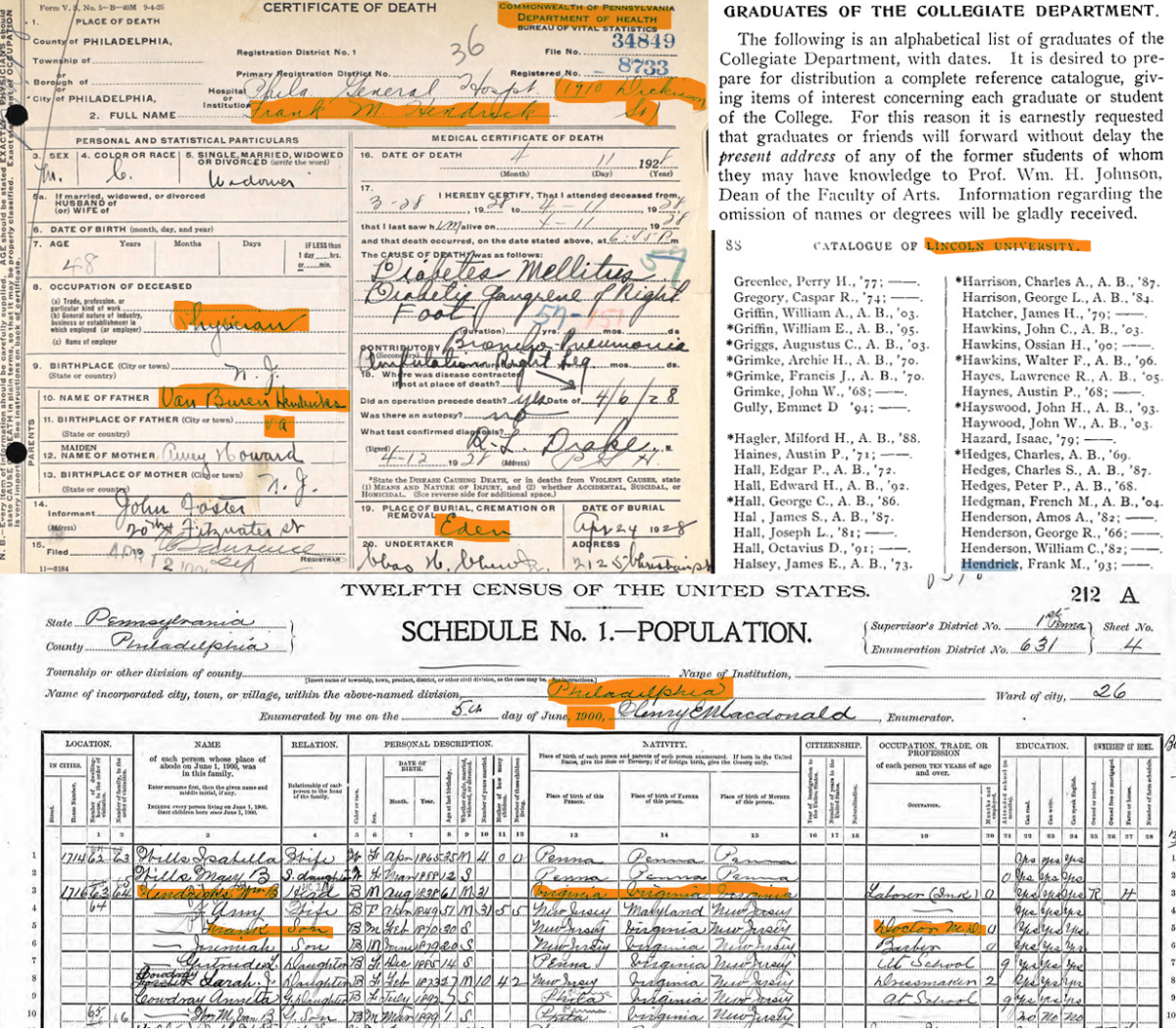

James M. Hendrick’s older brother William Van Burren Hendrick was named in the 1855-1865 Amelia County Free Negro Register. He moved to Woodstown, New Jersey, and then to Philadelphia. His son Frank M. Hendrick went to Lincoln University. Justice Thurgood Marshall and Langston Hughes also went to Lincoln University. Frank B. Hendrick became a medical doctor, and his office was on 1910 Dickinson St.

Union General Edward Ord did not die from wounds at Fort Harrison as stated in the above September 30, 1864, Richmond Whig article. In January 1865, he took command of the Army of the James for the Appomattox Campaign. After the Battle of Appomattox Court House, he was rumored to have paid the McLean family $40 (about $750 today adjusted for inflation) for the table that General Robert E. Lee signed the surrender papers on.

Bill Hendrick, one of many great-grandsons of Pvt. James M. Hendrick Sr. stated, “… it’s a mystery. …Why would someone with African American ancestry fight against freeing enslaved people.” Not every Hendrick in Amelia County fought for the Confederacy. Jordan Hendrick was listed as a free African American in the 1855-1865 register. Two of his sons were in the Union Army. James Powell Hendrick and Richard Hendrick enlisted in the 55th Massachusetts USCT Regiment. James Powell Hendrick died a few months after he enlisted. Richard Hendrick served through the end of the war.