The year 2026 marks the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Cardinal News has embarked on a three-year project to tell the little-known stories of Virginia’s role in the march to independence. As part of this, I will be writing monthly columns about the politics of the era, written the same way I’d write them today. The events described here took place in May 1765.

This project is supported, in part, by a grant from the Virginia American Revolution 250 Commission. You can sign up to receive a free monthly newsletter with updates.

I bring you shocking news from west of the mountains: Innocent blood has been shed and Augusta County has fallen to mob rule.

I refer to the brutal murder of five visiting Cherokees by a mob in Augusta County as they passed peacefully through the county — and the even more shocking riot that broke out when royal authorities attempted to bring the killers to justice. Augusta County may be a long way from Williamsburg and an even longer way from London, but it seems likely that this Native blood shed west of the mountains will eventually complicate life for our king across the water.

Allow me to relate these sad events, as reported by none other than Col. Andrew Lewis, who lately served in the French and Indian War and continued in military service since the conclusion of those hostilities.

In early May, a party of 10 Cherokees arrived in Staunton, led by Chachonante, the son of the former Cherokee chief Standing Turk. (Modern editor’s note: They most likely came from the Cherokee’s de facto capital in what today is Chota, Tennessee along the Tennessee-North Carolina border.) For those not familiar with the ways west of the Blue Ridge, it is not uncommon at all to see small parties of Native Americans passing through, although there is often much controversy as to whether this should be allowed. Those in Williamsburg may regard Augusta County as being out on the frontier, but those in Augusta believe the frontier is now farther west — and often resent the presence of even visiting Natives.

These Cherokees met with Lewis — “I was perfectly acquainted with some of them,” Lewis wrote in a letter to the governor — and told him their intention was to go on to Winchester and then turn west toward Fort Cumberland, where they intended to meet other Natives for the purpose of attacking Natives in the Ohio country.

Other dispatches in this series

Dispatch from 1763: King’s proclamation has united often opposing factions in Virginia (Opposition to the king’s proclamation forbidding western settlement.)

Dispatch from 1763: Despite cries of ‘treason!,’ Hanover County jury delivers rebuke to the church – and the crown. (The court case that made Patrick Henry a celebrity.)

“They requested passes and proper colors,” Lewis wrote in a letter to the governor. Lewis said “the want of an interpreter” made it difficult for him to impress upon the Cherokees that “travelling thro’ our country, even with a pass, where they might not be known, would be attended with danger on their part.” However, the Cherokees made it clear they were “determined to go,” so Lewis issued the Cherokees their requested passes and bid them on their way. The Cherokees went to John Anderson’s farm on Middle River where they spent several nights in an outbuilding on his property.

Virginia authorities in Williamsburg have generally tried to be cautious in their dealings with Natives, mindful that poor relations can lead to warfare. This was the spirit in which Lewis was acting when he granted safe passes to the Cherokees. Unfortunately, many ordinary subjects west of the Blue Ridge are not so discerning. They often regard any Native as a threat — and an obstacle to their goal of acquiring more land. This is where our king enters the conversation. His Proclamation of 1763 — which forbids settlement past a certain arbitrary line drawn through the mountains — remains extremely unpopular. While the king sees his restriction on western settlement as a way to reduce conflicts with the Natives, and thereby hold down security costs, those on the frontier see the king effectively siding with the Natives. That’s why what happened next holds political implications beyond Augusta County.

At dawn on May 8, a mob of about 20 to 30 white settlers — “a party of villainous bloody minded rascals,” Lewis called them — converged on Anderson’s farm and attacked the Cherokees “treacherously.” Five Cherokees were killed (including Chachonante), two others were wounded, three others escaped. One of the attackers, James Clendenning, was wounded by an arrow. Augusta authorities briefly arrested him but a mob of white settlers managed to free him before he could be taken to the jail. Another one of the killers, Patrick Duffy, was jailed for three nights.

On the fourth night, a mob of “not less than 100 armed men” surrounded the jail. “Then several entered the home of the jailer and demanded his keys to the prison,” Lewis writes. “When he refused to hand them over, they threatened him and then broke down the prison door with axes and carried off the prisoner Duffy, declaring they had the support of most of the county and they would never suffer a man to be confined or brought to justice for killing savages.”

Let me repeat this for those still trying to comprehend all this: An armed mob has risen up against royal authority and declared that it’s perfectly fine to murder the Natives.

Lewis promptly did two things. First, he sent a letter to the Cherokees informing them of the murders, begging them not to go to war (“take no rash steps”) and assuring them that the governor of Virginia will “undoubtedly take every just means to give them satisfaction by ordering the murderers to be apprehended and put to death.”

Having promised the Cherokees that the governor would take stern action, Lewis then wrote to Gov. Francis Fauquier to tell him what he’d just promised in his name — and requested arrest warrants be issued. When Lewis’ letter reached Williamsburg, Fauquier read it to the House of Burgesses, which was then in session. Fauquier described the legislators’ reaction was “shock” and told Lewis that the Burgesses expressed “abhorrence and detestation” at “so inhuman an action.” The governor said the legislators also “dread bad consequences” — another war with the Natives.

Fauquier seemed properly furious with the mob in Augusta. “If this is the conduct of your young men, with what face can they complain of Indians who are more than Indians themselves?” he wrote back to Lewis. “Can they produce greater instances of brutality and perfidy among the most barbarous Nations? Yet I imagine if any Indians should appear on our frontiers they would be among the first to call for protection, and by militia to put this Colony to the expence of twenty or thirty thousand pounds to defend them. I would ask themselves whether they deserve protection? and if hereafter they should be left to fight their own quarrels with the Indians without the lower parts of the Colony interfering in their disputes, they have no one to blame but themselves. I wish your County were made sensible of the risque they run of losing their property if not their lives by following and permitting these atrocious practices.”

The governor told Lewis to “spirit up” the magistrates in Augusta County to apprehend “these villains” and “to raise and arm as many men as you can safely depend upon, and as are necessary” to escort the suspects to Williamsburg, where they could be imprisoned more safely until they could be tried. The governor also told Lewis to tell Augusta County Sheriff Silas Hart to make sure he impanels a jury of “the Gentlemen of the County which are most distinguished by their property knowledge impartiality and integrity; and not leave it to the Under Sheriff, who may probably summon ignorant men who have little property or no property to lose, and of course have less reason to dread as they have less ability to foresee consequences.” For his part, the governor also sent his own emissary to tell the Cherokees he was dealing with the matter.

Augusta authorities have attempted to pursue a criminal investigation. We’ve been told that William Cunningham and John King have been identified as the ringleaders, with William Anderson, Charles Baskins, Hugh Baskins, Alexander Robertson and William Young joining Duffy and Clendenning as the principal associates. Depositions have been taken, and warrants sworn out but no one has yet to be arrested, much less transported to Williamsburg.

It looks now as if no one will be.

Tensions in Augusta County are still running high. A group has now formed calling itself the “Augusta Boys.” These vigilantes have now brazenly issued a “proclamation” in which they’ve offered 1,000 pounds to bring Lewis to justice! Mind you, this is the same Lewis who was renowned for his service in the late war. When Col. George Washington of Fairfax County was mistakenly informed that Lewis had fallen in battle, he issued a statement saying that Lewis’ death was “a great loss to the Regiment and is universally lamented.” Fortunately, that was a false report, and Lewis remains very much among us — except now he’s being vilified by his fellow countrymen for daring to try to arrest accused murderers! Those same Augusta Boys also issued a 500 pound reward for two of Lewis’ allies, Dr. William Fleming and Capt. William Crow, as well as mockingly offering pardons to Lts. Michael Thomas and Luke Bowyer if they provide “a string of beads” and quit the militia and “live as formerly without depending alone on the smiles of Col. Lewis.”

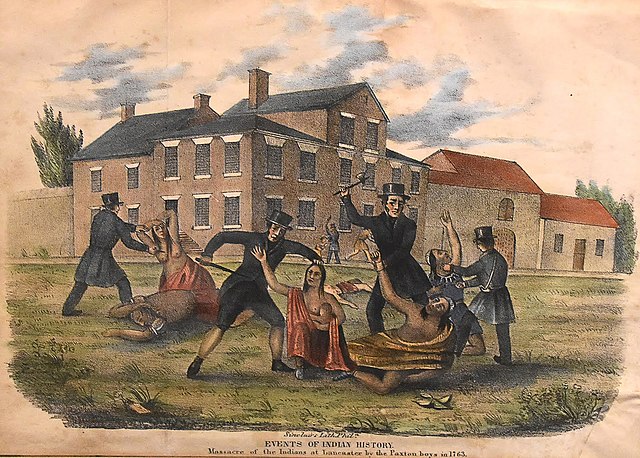

It’s worth noting that this isn’t the first time a mob of white settlers has wantonly murdered Natives. In Pennsylvania, the so-called Paxton Boys gang — 50 or so strong — murdered six members of the Conestoga tribe who had lived peacefully side-by-side with the colonists for years. Authorities gave 14 members of the tribe refuge in the local workhouse but about two weeks later the Paxton Boys showed up and killed them — even dismembering the bodies of Native women and children.

Who can forget the horrific account of eyewitness William Henry: “I saw a number of people running down the street towards the gaol, which enticed me and other lads to follow them. At about sixty or eighty yards from the gaol, we met from twenty-five to thirty men, well mounted on horses, and with rifles, tomahawks, and scalping knives, equipped for murder. I ran into the prison yard, and there, O what a horrid sight presented itself to my view! Near the back door of the prison, lay an old Indian and his women, particularly well known and esteemed by the people of the town, on account of his placid and friendly conduct. His name was Will Sock; across him and his Native women lay two children, of about the age of three years, whose heads were split with the tomahawk, and their scalps all taken off. Towards the middle of the gaol yard, along the west side of the wall, lay a stout Indian, whom I particularly noticed to have been shot in the breast, his legs were chopped with the tomahawk, his hands cut off, and finally a rifle ball discharged in his mouth; so that his head was blown to atoms, and the brains were splashed against, and yet hanging to the wall, for three or four feet around. This man’s hands and feet had also been chopped off with a tomahawk. In this manner lay the whole of them, men, women and children, spread about the prison yard: shot-scalped-hacked-and cut to pieces.”

Many of the Paxton Boys are of Scots-Irish heritage, prompting Benjamin Franklin of Philadelphia to write that the Conestoga people would have been safe “among any other people on earth, no matter how primitive, except ‘the Christian white savages’ of Peckstang and Donegall!”

I relate that Pennsylvania story because those same Pennsylvania vigilantes have now reached out to the Augusta Boys to form an alliance. Gov. Fauquier has confirmed this, saying that the Paxton Boys have told the Augusta Boys that if they are not strong enough to stand up to colonial authority, then the Paxtons will come help them. The governor has even written London to tell authorities there that it is “the wiser course” to be “extremely prudent rather than attempt vigorous action in Augusta County.”

Translation: The governor intends to do nothing.

Lewis has warned that if Virginia authorities don’t suppress this mob rule in Augusta, only bad things will happen when word about these killings get back to the Cherokee nation. “All thinking settlers,” especially those most acquainted with the Cherokees, Lewis wrote, “fear the consequences of the senseless murders.” Indeed, we’ve seen some tragic consequences already: “Several days after the murders, a poor unhappy blind man and his wife were killed by two Indians who made their escape,” Lewis wrote. However, it appears that most settlers in Augusta don’t live up to Lewis’ expectation of “thinking settlers” who seek good relations with the natives. Public opinion seems to be on the side of the vigilantes, and the governor would rather risk the unknown long-term consequences of inaction rather than the short-term consequences of trying to enforce the law in Augusta.

This may all seem some isolated incident in a turbulent west that’s often easy for those in the east to overlook, but I call your attention to this: What we’re seeing in Augusta County is essentially a class uprising against the gentry, both locally and beyond. It’s also ultimately an uprising against royal authority, brought on partly by resentment against the king’s Proclamation of 1763. If these mobs had their way, there’d be no Natives left anywhere, and every time they see a Cherokee party passing through the Great Valley they are reminded that the king won’t let them push the Natives farther west. The Augusta Boys profess that “our hearts are true unto our king” but their actions sure suggest otherwise.

Sources consulted include “Forced Founders: Indians, Debtors, Slaves And the Making of the American Revolution in Virginia” by Woody Holton, “Life Under Four Flags in the North River Basin of Virginia” by C.E. May, “Across the first divide: Frontiers of settlement and culture in Augusta County, Virginia, 1738-1770” by Nathaniel Turk McCleskey, the Native Heritage Project and Mount Vernon’s digital encyclopedia.