Got questions about Virginia’s laws on weed? We’ve got answers in our FAQs on the state’s cannabis policies.

Two rival bills that would legalize the retail sale of marijuana are before the General Assembly. Both might fail, and both might get vetoed by Gov. Glenn Youngkin, who has made it clear he’s not just interested in cannabis. On the other hand, one of these might indeed pass and Youngkin might find himself having to sign it if he wants his deal to bring the NBA’s Washington Wizards and NHL’s Washington Capitals to Alexandria to go through.

The Washington Post recently quoted an anonymous Democratic legislator saying that the legislative price for their votes on the arena will be high: “We don’t just want a pound of flesh, we want a ton.”

Sen. Louise Lucas, D-Portsmouth and chair of the Senate Finance Committee, has made it clear that she wants tolls on the two tunnels that connect her city with Norfolk removed or reduced. At some point, every legislator whose support for the arena deal is in question might have a price. For a lot of those Democrats (including Lucas), that price might be Youngkin’s acquiescence to a cannabis bill. (While Youngkin has made it clear he doesn’t think retail cannabis is a good idea, it’s notable that he also hasn’t pledged to veto such a measure.)

With that in mind, let’s look at the two cannabis bills and see what, if anything, they mean for the parts of the state farthest from the arena: Southwest and Southside. Keep in mind that there are other differences between the two bills — who’s eligible for licenses, who gets them first, the role of large companies versus small ones, how much “social equity” fits into things. For those details, I refer you to the story that Cardinal’s Markus Schmidt wrote about cannabis legislation. Instead, I’ll focus more directly on the regional implications.

Finally, a clarification of sorts: I’ve referred to two bills. There are actually three. Sen. Adam Ebbin, D-Alexandria, and Del. Paul Krizek, D-Alexandria, have separately introduced the same bill: SB 423 in the Senate, HB 698 in the House. For our comparison purposes today, those are the same bill, even though they’ll be handled separately in each chamber. The other bill is by Sen. Aaron Rouse, D-Virginia Beach — SB 448.

How licenses (and jobs) would be distributed statewide

If left completely to the free market, the odds are high that most cannabis stores would go to metro areas — that’s where the people are — and the other parts of the cannabis supply chain, from cultivation facilities to processing facilities, would wind up nearby. Since that’s where most of the state’s people are, that’s also where most of the workforce is. Locating the supply chain near the customer base would also reduce transportation costs. That means if you’re looking at the bills in terms of what they’d mean for Southwest and Southside, the question is how much they try to enforce some kind of geographical distribution of cannabis jobs, which might be an important political point for any Republicans who can be persuaded to get on board.

The Ebbin-Krizek bill mandates specific quotes for how cannabis businesses be distributed around the state; the Rouse bill does not, although I’m told by lobbyist Greg Habeeb that the final version will direct the Cannabis Control Authority to manage a geographic distribution.

Otherwise, the Rouse bill simply spells out the number of licenses allowed: 450 cultivation facilities, 60 processing facilities, 50 transporters, 400 retail stores.

The Ebbin-Krizek bill doesn’t give specific numbers for the number of licenses, but it spells out how they should be distributed around the state: at least five cultivation licenses, five processing licenses, five wholesale licenses and eight retail store licenses in each state senatorial district.

Virginia has 40 state Senate districts, so that would mean at least 200 cultivation licenses, 200 processing licenses, 200 wholesale licenses and 320 retail scores overall. Here’s what that would be in practical terms. The state’s westernmost senatorial district — represented by Todd Pillion, R-Washington County — covers seven counties and two cities in the state’s southwestern corner, from Bristol and Washington County to the west. That district would get at least five cannabis cultivators, at least five processors, at least five wholesalers and at least eight stores.

By contrast, the state Senate district around the Roanoke Valley — represented by David Suetterlein, R-Roanoke County — covers Roanoke, Salem, most of Roanoke County and most of Montgomery County. The one around Lynchburg — represented by Mark Peake, R-Lynchburg — covers Lynchburg, Campbell County and most of Bedford County. Each of those metro areas would get at least five cannabis cultivators, at least five processors, at least five wholesalers and at least eight stores.

There is a provision in both bills for localities to opt out of either retail sales or the whole cannabis supply chain — more on that to come.

The big point here is that the Ebbin-Krizek bill would guarantee that some cannabis jobs wind up in all parts of the state; the Rouse bill delegates that to the Cannabis Control Authority.

How localities can opt out

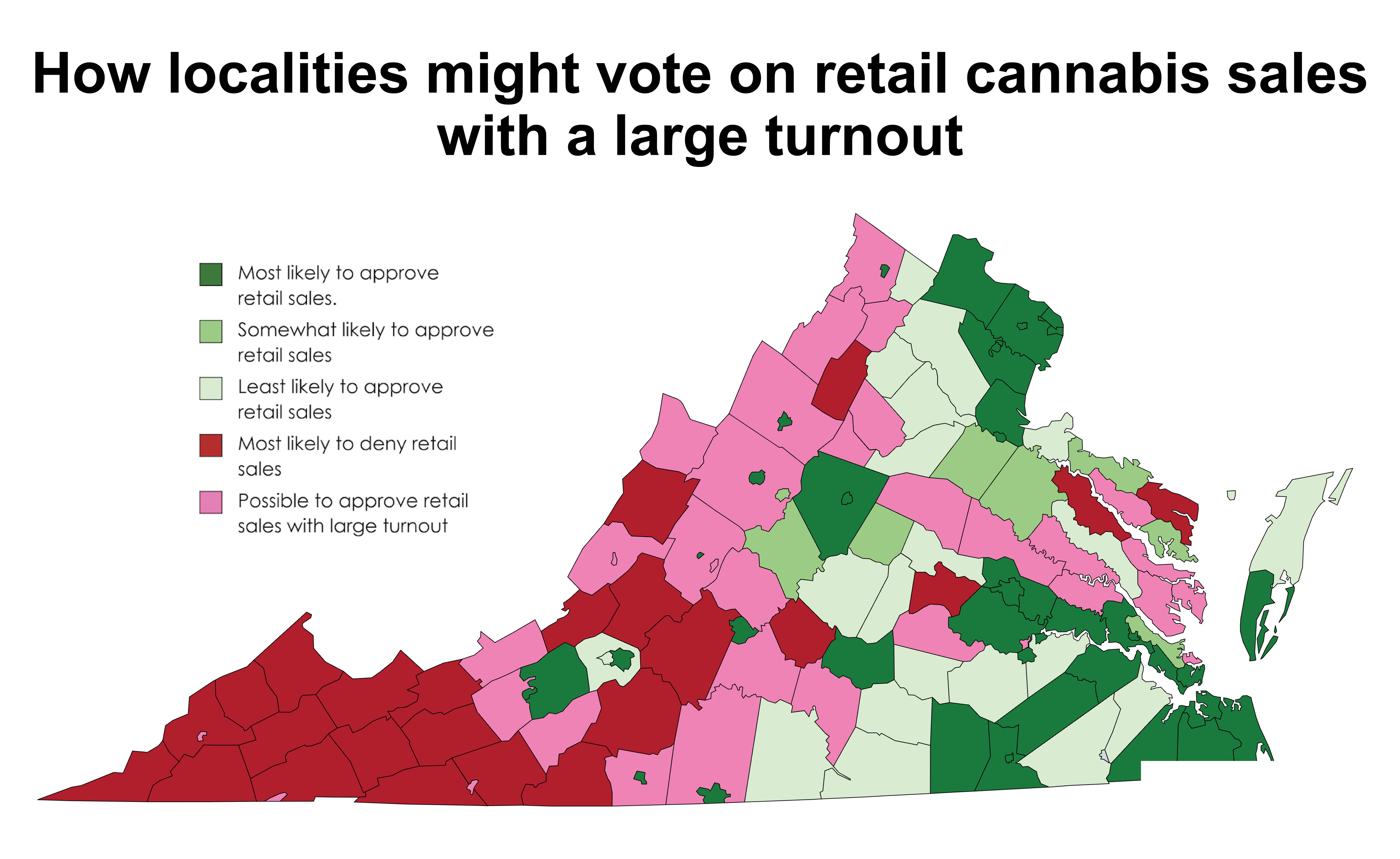

Both bills presume that cannabis businesses are allowed unless they’re banned via a local referendum. Both bills also require that such referendums be held in November 2024 — coinciding with our highest-turnout election, a presidential election. That’s a political advantage to pro-cannabis interests. In previous columns, I’ve looked at referendums in other states. In general, the higher the turnout, the better cannabis does. That would be significant in certain rural communities; I’ve tried to analyze before which localities would likely vote for cannabis, which ones would vote against, and which ones might go either way.

Both bills also say that such referendums on local prohibition are one-and-done deals. If a locality votes “no” to prohibition, and therefore allows cannabis, then cannabis is allowed forever — a locality can’t change its mind later. If a locality votes “yes,” and decides to ban cannabis, that ban can be undone in a future referendum.

The two bills differ, though, in terms of what can be banned.

The Rouse bill says that localities can only ban retail stores — not cultivation centers or processors. The Ebbin-Krizek bill allows localities to ban any “marijuana establishment.”

That’s where things get interesting: Under the Rouse bill, the campaign in some future local referendum will likely focus on how you feel about cannabis being more widely (or least more legally) available. Should we allow a pot store in our community? Nothing more, nothing less. A locality could nix stores but still land some cultivation and processing jobs, which might be the sweet spot for some queasy rural Republicans. Under the Ebbin-Krizek bill, those local referendums would also be about the entire cannabis supply-chain — and many of those cultivation and processing operations are where the best-paying jobs in the cannabis industry are. Sure, you may not want a store, but what about all the cultivation and processing jobs we might get? It’s akin to a liquor-by-the-drink referendum being not just about cocktails at a local restaurant, but about a potential brewery, as well. That creates a very different kind of campaign. On one side, those who think cannabis is bad. On the other side, those who say the measure is good for economic development.

I’ve tried to speculate before about which localities might approve retail weed, based on referendums in other states. Here’s my analysis that produced the map above after South Dakota’s vote in 2022, with a more recent analysis after Ohio’s vote in 2023, which suggests some of those red “no” counties in Southwest Virginia might actually vote yes.

Greenhouses or outdoor growing?

The Rouse bill allows for outdoor cultivation. The Ebbin-Krizek allows the Virginia Cannabis Control Authority to ban outdoor cultivation. It’s unclear how big a deal this difference is. In Colorado, one of the pioneers for legal weed, about 15% of legal cannabis is grown outdoors, according to New Frontier Data. The advantage of outdoors: It’s cheaper and connoisseurs contend it’s better quality. The advantage of indoors: The crop is more secure, isn’t subject to the vagaries of weather and can be grown year-round.

We’re seeing growth in indoor agriculture even without cannabis, so I wouldn’t bet much money on seeing any big weed farms even under the Rouse bill. That’s where the Ebbin-Krizek requirement that at least five cultivation licenses go to each senatorial district becomes important. We’re going to see cannabis in Virginia grown indoors, and if it’s grown indoors, there’s no reason for it to be in traditional agricultural areas; those indoor ag facilities could be in downtown Richmond. The Ebbin-Krizek provisions make sure that rural areas still get a share of the jobs — assuming that voters decide not to ban them.

So which bill is better? That’s a matter of taste. Some may not want either bill to pass. Some may prefer the free market deciding where the cannabis industry goes rather than having government dictate its distribution. Ironically, Republicans — who generally prefer free market solutions — are the ones whose rural districts would benefit most from the bill by two Northern Virginia Democrats that would make sure some of the cannabis jobs go to rural communities.