Perhaps Billy Wagner should have carried a map of Virginia with him in the Major Leagues.

Whenever one of baseball’s all-time great relief pitchers opened his mouth in the cosmopolitan world of the modern professional game, and that Southwest Virginia twang came out, Wagner knew what the follow-up question would be.

“Where are you from?” the reporters would ask, often with a hint of astonishment.

Tazewell County was an easy one to explain, Wagner said. It’s in the mountains they pull all that coal out of.

But Ferrum College? That was another thing entirely.

“Well, it’s between Endicott and Callaway,” Wagner explained in his matter-of-fact tone, like any old reporter from Houston or New York would be familiar with Franklin County’s geography.

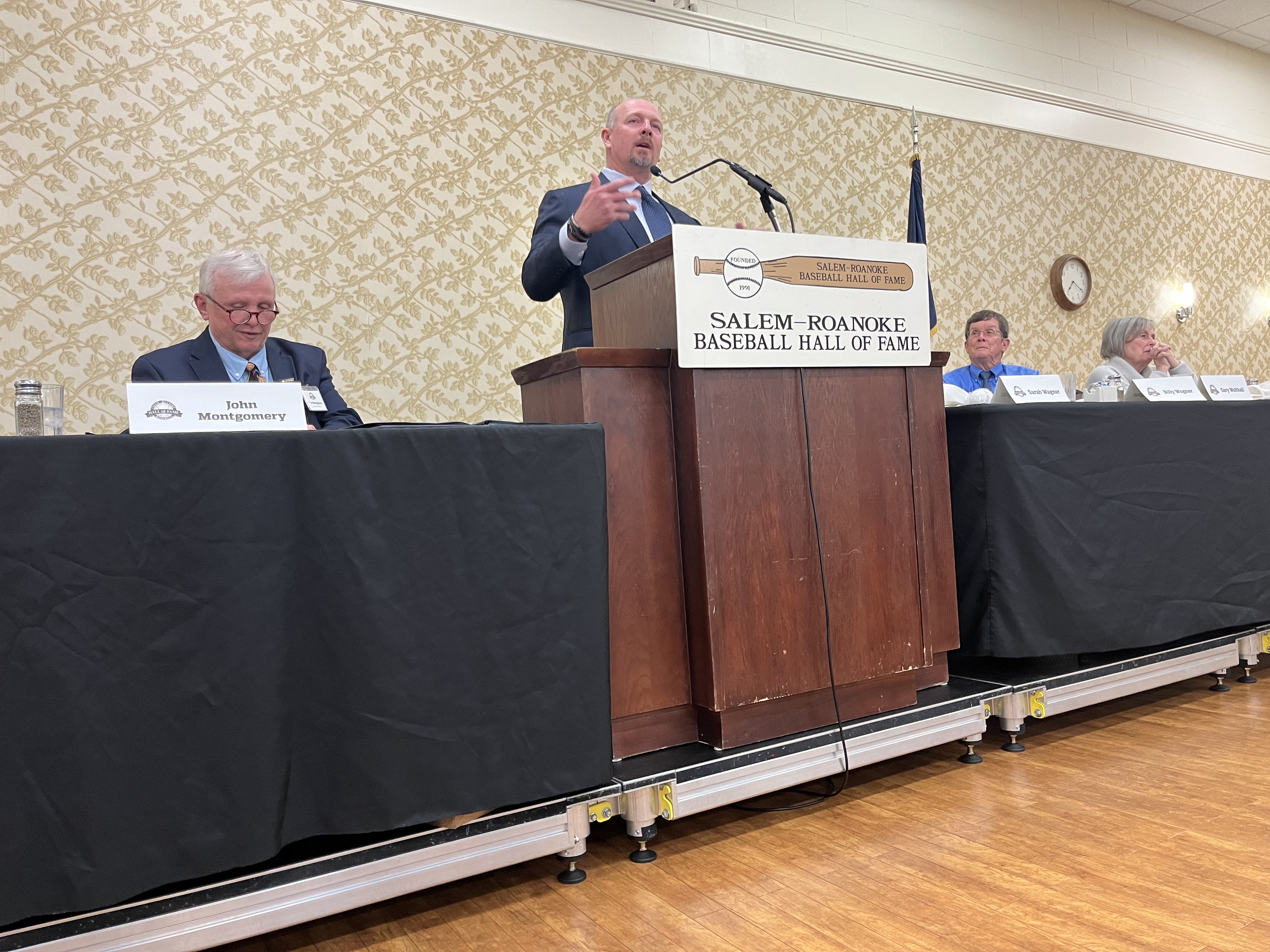

Wagner visited his old stomping grounds in the Roanoke Valley on Sunday as the keynote speaker for the Salem-Roanoke Baseball Hall of Fame induction ceremony, regaling a crowd at the Salem Civic Center with stories of his days in baseball from Tazewell County to Ferrum College to the Major Leagues.

He spoke emotionally about his days at Tazewell and Ferrum — especially moved in remembering a mentor in former Major Leaguer and Franklin County legend Ron Hodges, who died in November — and laid a message to the many coaches in the room about the lives they influence through the sport.

One of the greatest relief pitchers in the history of baseball, Wagner has been at the spotlight of the sport’s national coverage in recent years as voters review his case for the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. He garnered 73.8 percent of the vote from the writers this year, just five votes shy of the 75 percent he needed for enshrinement; 2025 will be his 10th and final year on the ballot. No one who has ever come that close to being voted into the hall has failed to make it in a subsequent year.

But for Wagner, it’s been the people along the way who defined his story, both in baseball and life outside the national pastime.

It started with family. Wagner grew up in a large one, and his uncles and cousins were Tazewell athletics royalty. Sports were always in season. In the fall it was football, and in the spring and summer, baseball. And Wagner had football to thank for unlocking the secret that would earn him millions and establish him as one of the great closers (a relief pitcher who specializes in getting the final outs of close ballgames) in the history of the game.

Naturally right-handed, a 7-year-old Wagner was playing football in his grandmother’s yard when another boy landed on his right arm and broke it. Not long after the injury healed, Wagner broke the arm again on the playground. So with his dominant arm castbound, he began to throw left-handed.

But Wagner was quick to admit he wasn’t the best player on those Little League diamonds.

“I was the guy peeing on myself or grabbing flowers, whatever,” he said with a laugh. “I was that kid. I wasn’t interested.”

But Wagner’s father and grandfather coached his teams growing up, a constant reminder to live up to the family name.

“If I wouldn’t have had those people as the bar-setters, I would not have known how to push, to fight,” he said.

At Tazewell High, he played for the late Lou Peery. One of the first Black student-athletes at Emory & Henry College, Peery coached the Bulldogs from 1979 to 2013 and won more than 400 games. The secret sauce, Wagner said, was in the way Peery treated folks.

“What he taught me was that everybody was the same,” the pitcher said. “He didn’t treat me any different than he did anybody else.”

That, and baseball was never more important than people. Even after Wagner made the Major Leagues and became one of the game’s elite relief pitchers, he said he’d hear from his high school coach.

“He would call me during times I wasn’t doing very well and have a conversation, and nothing would be about baseball,” Wagner remembered. “He would always talk about my family.”

Wagner shined as a high school star at Tazewell, the hardest thrower in the region by far, but the combination of a small school and his small stature resulted in a lack of attention from the country’s top collegiate baseball programs. He passed on some walk-on offers at bigger schools and chose Ferrum, where he had the opportunity to play both football and baseball. But after a year of football, the diamond won out. Wagner played on some of the most talented NCAA Division III baseball teams of the 1990s, advancing to three NCAA tournaments and winning a pair of Dixie Conference titles with the Panthers. But years in the rearview, it’s the people his stories return to.

“You can’t appreciate it unless you’ve been there. That’s what I always tell them,” Wagner said. “People coming out of the hills and sitting on the bank with a jug. You just can’t enjoy it unless you see that.”

And people like Abe Naff, the longtime Ferrum coach and athletic director. He remembered Naff’s steady hand as Ferrum took on a scholarship program, University of Pittsburgh, in Wagner’s first collegiate game. Ferrum, vastly outmatched on paper by the scholarshipped players in the other dugout, beat Pitt with the intensity and confidence his coach instilled in the talented team. It was never personal, Wagner said, and it was always about doing what was best for the team to win.

“Me and him would just be seizing at each other … and then after the game was over, not a thing,” Wagner said.

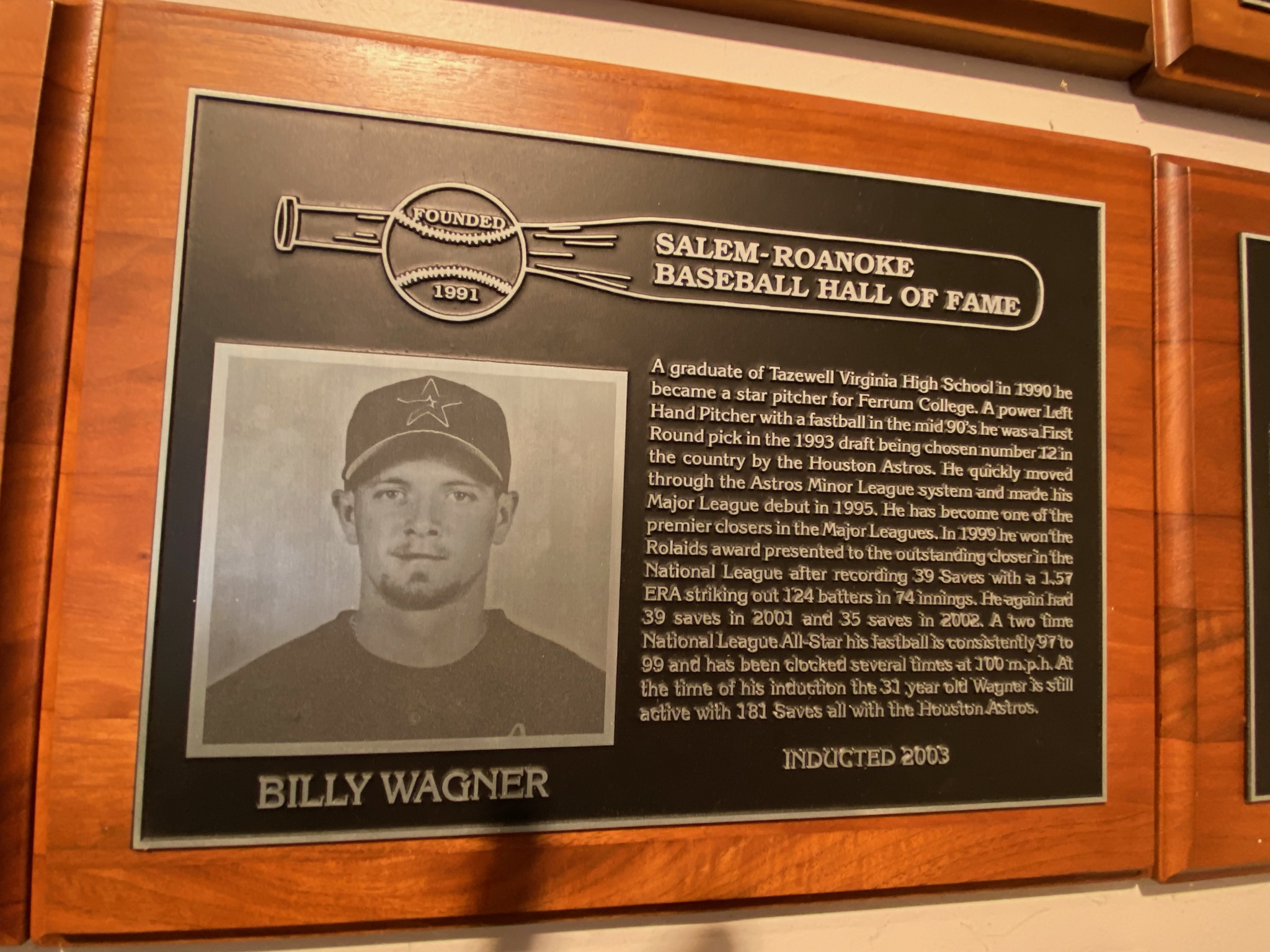

He went on to greatness in three years pitching for Ferrum, setting career Division III records for strikeouts per nine innings and fewest hits allowed per nine innings, and was drafted 12th overall in the 1993 MLB Amateur Draft by the Houston Astros.

Wagner made his MLB debut in 1995 and spent 16 years in the majors, pitching for the Houston Astros, Philadelphia Phillies, New York Mets, Boston Red Sox and Atlanta Braves. He was selected to five all-star teams and amassed the sixth-most saves, 422, in the history of the game. (A relief pitcher earns a save by entering the game with a lead of three runs or fewer and finishing that game with the lead intact or by pitching the final three or more innings of a game without relinquishing the lead.) Wagner’s 11.9 strikeouts per nine innings remains the highest for any MLB pitcher with at least 900 innings since 1900.

Even in the Major Leagues, though, it remained about people. People like Charlie Manuel, the Buena Vista native who managed Wagner in Philadelphia.

“They don’t talk like us,” Wagner remembered warning Manuel when the latter was offered the job as the Phillies manager.

And people like Jimy Williams, his manager for two seasons in Houston who passed away last week.

“I would have pitched ‘til my arm fell off for that man,” the lefty said. “I felt like he truly cared about me as a player. … He wanted to win as much as I wanted to win, and I wanted to win for him.”

Wagner retired after the 2010 season still at the top of his game; Wagner pitched to a 1.43 earned-run average and totaled 37 saves for Atlanta in his final campaign.

“Truly it was about my kids,” Wagner said. “After the sacrifice my wife had made and the kids had made to follow me everywhere. … Whatever people want to make of it, I was happier being home.”

Career stats and facts

Earned run average: 2.13

Saves: 422

Strike-outs: 1,196

First Major League game: Sept. 12, 1995 for the Houston Astros

Final Major League regular season game: Oct. 3, 2010 for the Atlanta Braves. Struck out the last three batters he faced.

Final Major League game: Oct. 8, 2010, for the Atlanta Braves in Game 2 of the National League Division Series.

So home Wagner went, raising his four children beside college sweetheart Sarah. Eventually he landed in the Charlottesville area as the baseball coach at Miller School, a private school where he has guided the Mavericks to three state titles in 10 seasons and continues to coach in the styles he learned from people like Peery and Naff.

His children have thrived athletically in Wagner’s post-playing days as well. His oldest son, Will, starred at Liberty University and reached AAA, the highest level of Minor League Baseball, last season. His second son, Jeremy, plays baseball at Towson University, and daughter, Olivia, is on the basketball team at Radford University. The youngest son, Kason, plays for his father at Miller.

“It was a big blessing,” Wagner said of seeing his children play sports. “I don’t try to give them a lot of advice and stuff like that, but it’s good to be there to see it, be the sounding board.”

And so while his Cooperstown case may dictate the Billy Wagner narrative in the national media, the account in his own mind is settled.

“Whether Hall of Fame is ever mentioned on my name,” he said, “I think it’s just one of those things that I’ve been so blessed that I could never be upset or angry about where I’m at.”