Want to read more about Virginia’s changing demographics? We’ve collected all our coverage in one place.

In Roanoke County, the school system has sold a 55-acre farm in Poages Mill that it bought in 2007 as the site for a new school that never happened after enrollment gains turned into enrollment declines.

In Lynchburg, the school system is closing schools because enrollment is declining even as the city’s overall population rises.

In Franklin County, enrollment declines — and a quirk of the state’s funding formula that has reduced state aid more than the county expected — have forced the county to contemplate the closure of up to five of its 12 elementary schools.

These are just three examples of how demographics, specifically declining birth rates, are driving public policy, often in uncomfortable ways. Of these, the Franklin County situation is the most dramatic and the most unexpected — and perhaps the most urgent. The Franklin County Board of Supervisors has called a special meeting for Thursday to discuss the situation.

In the past few weeks, the Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service at the University of Virginia released two different sets of data that help us better understand how our communities are changing: projected enrollment figures and population estimates. Let’s dive into those to see what we can find that might help both Franklin County officials and anyone else who wants to understand what’s going on.

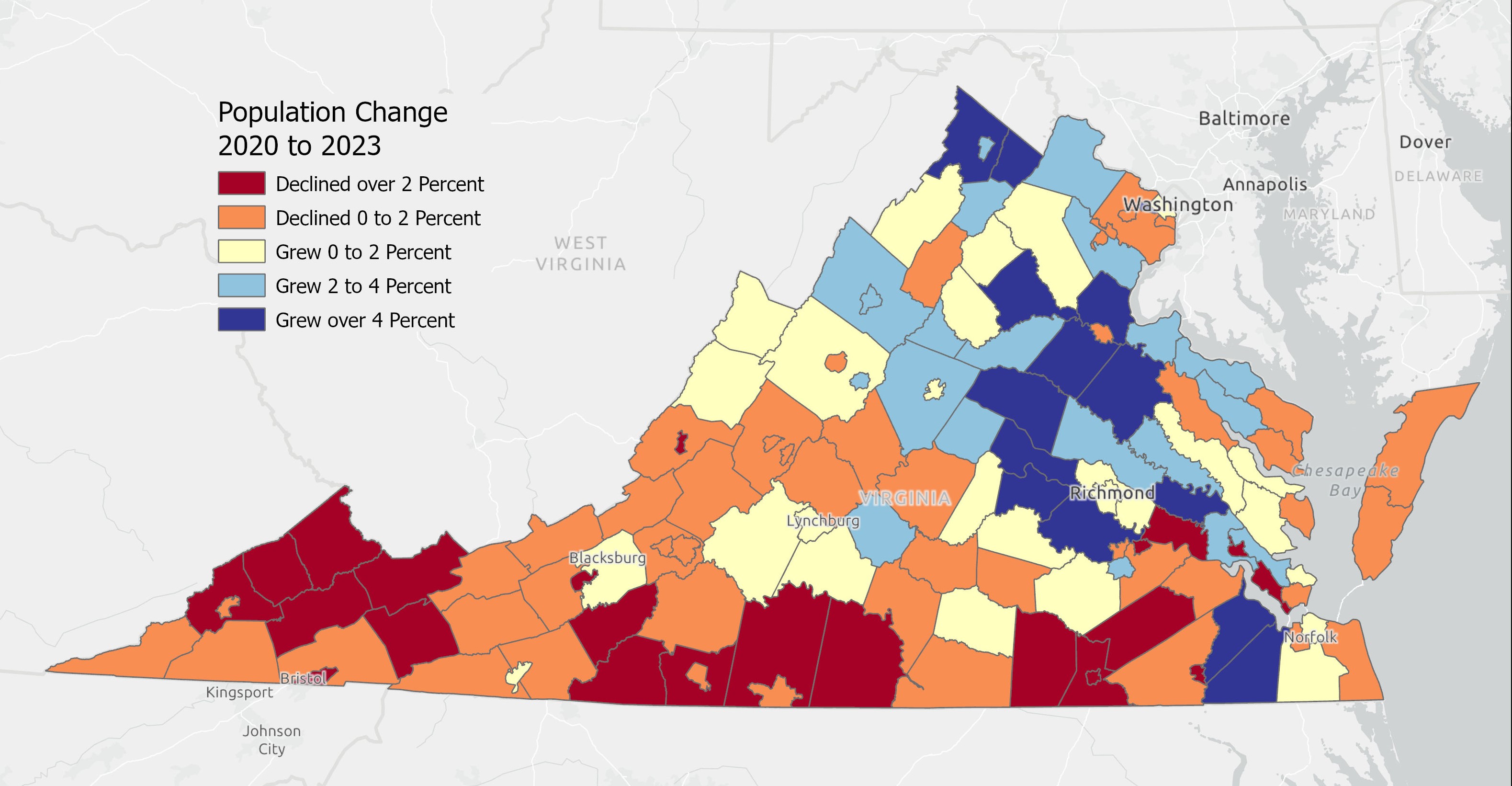

For those not familiar with Franklin County, this news about possibly closing almost half the county’s elementary schools is a shock because, while much of rural Virginia has been losing population for years, Franklin County has been until late one of the fastest-growing counties in the state. Why and how that’s changed so rapidly is potentially instructive for those beyond Franklin County.

For the first half of the 20th century, Franklin County was much like other rural counties in Virginia. Its population hit 26,480 in 1910 and then started declining as cities drew away farm workers, a reflection of an economy transitioning from the agricultural age to the industrial age. By 1950, Franklin County’s population had dropped to 24,560 — not a precipitous decline, but still a decline. It gained back some, but not all, of that lost population during the baby boom of the 1950s.

What really changed Franklin County — and neighboring Bedford County, too — came on April 26, 1960. That’s when the Federal Power Commission approved the hydroelectric project that became Smith Mountain Lake. On March 7, 1966, at 5:03 a.m., Franklin County changed again — that’s when the lake reached full pond and the 500 miles of shoreline began to turn into a brand new community and a magnet for retirees. From that point on, Franklin County’s population surged. During the 1970s, Franklin County’s population grew by 33.1%. For 50 years — half a century — Franklin County consistently posted double-digit growth rates, typically adding about 8,000 or 9,000 new residents every decade. By the 2010 census, Franklin County was home to 56,159 people, more than double what it had been when the lake was built. It looked as if Franklin County would keep growing forever — except it didn’t.

After posting an 18.8% growth rate in the 2010 census, the 2020 census found that Franklin County’s population growth hadn’t simply slowed, it had stopped, and the county was now losing population — down 3% to 54,477.

What happened?

Lots of things had happened — the recession of 2008, for instance, slowed housing. The biggest thing that happened, though, is that Franklin County simply aged out. That’s a gentle way to describe things.

Put more bluntly, those retirees who had flocked to lakefront property were dying off.

The latest Census Bureau estimates say that Franklin County has lost 0.5% of its population since 2020. There are certainly places that have lost population at a faster rate but this is obviously a marked contrast to the double-digit growth rate that Franklin County once had — and an indication that the 2020 census count wasn’t wrong.

When we look closer, we can see exactly how Franklin County’s population has shrunk: mostly through death. Over the past three years, deaths have outnumbered births. In demographic terms, Franklin County’s “natural decrease” — deaths over births — is -786.

Franklin County has more people moving in than moving out — it has a net in-migration of 491 — but that doesn’t make up for the 786 deaths-over-births number. Franklin County is gaining some people through moving vans but losing more through hearses.

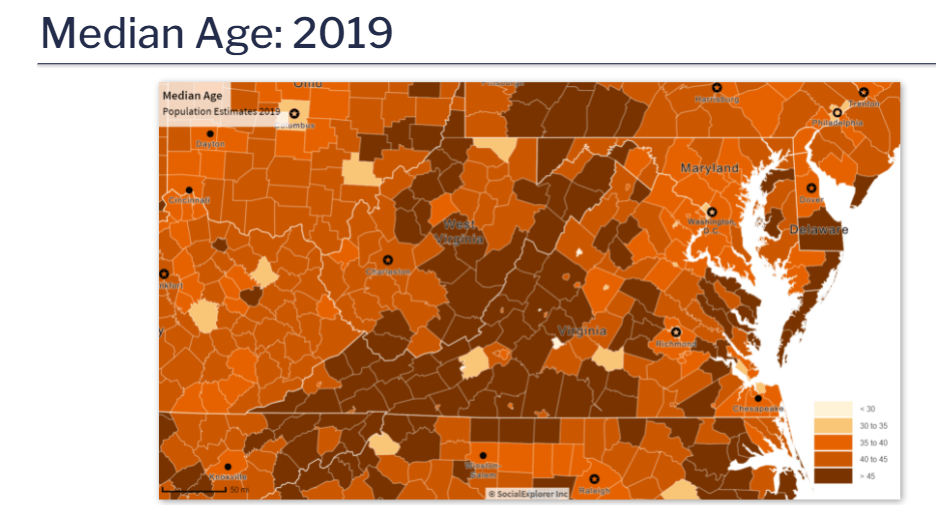

None of this should be surprising if you look at the statistics. In 1980, Franklin’s median age was 30.5, making it one of the youngest counties in Virginia. By 2022, its median age was put at 48.5, making it one of the oldest. To be fair, much of rural Virginia has seen median ages rise over the years, a combination of longer life spans and young adults moving out. Franklin’s shift is simply one of the more pronounced, skewed by Smith Mountain Lake. Franklin County’s population growth was once powered by retirees, but those retirees weren’t having children. And people who weren’t retirees weren’t having many. This is the inevitable result: a declining population overall and declining enrollment, in particular.

Even with Smith Mountain Lake, Franklin County is not unusual in its overall trends: Most localities in Virginia are facing enrollment declines, even some of those that are gaining population. Birth rates have been declining, almost constantly, since 1957. When lots of people are moving in, and bringing children with them, or having children, that helps make up for those declining birth rates. However, Franklin County isn’t seeing that much in-migration. The census numbers don’t tell us the age of those people moving into Franklin County — are they still people past childbearing years or not? — but even if they all were, those numbers are still fairly modest. By contrast, Bedford County’s net in-migration the past three years has been 2,100; that’s because Bedford has Lynchburg growth spilling out into the Forest area.

However, even with all that net in-migration, even Bedford County’s enrollment is projected to decline over the next five years — by 2%. Franklin County’s is projected to drop by 7%. That’s one of the largest projected decreases on this side of the state. To the east, Pittsylvania County’s enrollment is projected to decline by 4%. To the west, Roanoke County’s is expected to fall by 2%. Franklin County’s enrollment situation is more akin to Henry County to the south, where enrollment is projected to fall by 9%.

Things get even worse for Franklin County. (Sorry to be the bearer of bad news, but people in Franklin need to know these numbers so they can make good policy decisions based on facts and not emotion.) Virginia’s school funding formula penalizes Franklin County. I wrote some about this in a previous column and will have more to say in a future column but here’s the essence of it: The dreaded Local Composite Index relies heavily on property values to determine a locality’s ability to pay for its schools — the more ability it has, the less it gets from the state; the less ability it has, the more it gets from the state. That may work well in some instances but not for a county such as Franklin County; all that development around the lake makes Franklin County look as rich as Croesus, even though most of the county isn’t.

That funding formula also factors in enrollment — more students, more state funding; fewer students, less state funding. That makes sense, except that some costs don’t decline when enrollment does. You still need a first-grade teacher whether you have 20 students or 10; you still have to heat the building no matter how many students are in it; you still have to run bus routes over the same roads no matter how few students that bus is picking up.

Here’s how all that plays out in Franklin County: The Local Composite Index says that Franklin County, which has a median household income of $66,275 and a student poverty rate of 47.29%, is better able to pay for its schools than Prince William County, where the median household income is $123,193 and 32.69% of the students live in poverty.

All these things — an aging population, a declining birth rate, a relatively low net in-migration rate, a state funding formula rigged against it — conspire against Franklin County. This is why it’s facing the prospect of closing schools.

What can the county do about this? In the short term, it could close some schools and move on. Or it could raise taxes. Franklin County’s real estate rate is 61 cents per $100 of assessed value. Here in Botetourt County, I’m paying 79 cents. In Roanoke County, it’s $1.06. On the other hand, Bedford County’s rate is 41 cents. These are all choices communities have made about what level of services they’re willing to support. I hate to be the guy who says “just raise your taxes” because I don’t like paying taxes, either. I’m just pointing out one of two not-so-good immediate options. There aren’t many options to close these funding gaps — you either need to reduce expenses or raise revenues. Franklin County can either close schools or raise more revenue to keep them open. Which will it be? Yes, maybe the state will change its formula funding in a way that helps or at least doesn’t penalize Franklin County, but no one should wait on that, or you may be waiting a long time. Maybe there are some other funding choices the county can make — cutting something here to pay for schools over there — but those are also potentially painful choices and may not have a lasting impact.

The overarching policy question Franklin County residents need to wrestle with is how much do they value holding onto all the schools they do now. If they want to hold onto them — and nobody likes closing schools, either — they have some unpleasant immediate choices and some clearer but still difficult long-term options.

If Franklin County wants more students in its schools to justify keeping them all open, then Franklin County needs more people — and more younger people. That probably means Franklin County needs more housing — people have to live somewhere. It also probably means Franklin County needs more jobs, unless the county intends to rely completely on commuters into the Roanoke Valley. The Summit View Business Park was controversial when it was built, but all these things are connected — if you want more local jobs, they have to be somewhere, too. Yes, I realize all these things pose a challenge for a county that also wants to retain its rural character. Again, I’m just laying out the options.

Franklin County’s ability to attract some manufacturing jobs is currently limited by its lack of natural gas. Yes, natural gas pipelines are controversial, but the reality is that’s what a lot of manufacturers are looking for. I don’t make the economic rules; I just explain them. The Mountain Valley Pipeline says it will have a tap in Franklin County when it’s completed but it’s not completed yet. Maybe renewables are an option for some employers — they are certainly a preference for certain types of businesses — but Franklin County has also set limits to restrict the growth of solar farms. That certainly preserves some farmland, and some viewsheds (if you think solar panels are ugly, that is), but it also eliminates certain types of prospective employers. Maybe those employers would never come even if Franklin County paved over every inch of green space with solar panels, but all these decisions have consequences, both pro and con.

If Franklin County residents want to keep their schools open, they need to be clear-eyed about what it will take to do that: an economic development strategy geared toward attracting more young adults to the county, and that strategy may involve choices that some may not like. Which land will be developed? How will the county attract employers without certain energy options available? What quality of life amenities does the county need to develop at taxpayer expense? What should the tax rate be, so that it’s both affordable but also pays for the things the county values? If these weren’t the issues in the most recent supervisor races, they certainly ought to be in the next ones. For now, it’s simply how much is Franklin County willing to pay to keep all its schools open — knowing that closing some schools probably makes it less likely that the community involved will attract the young adults the county needs, but paying to keep them open may stress the landowners already there.

They say that demography is destiny and that’s true, but destinies can be changed. The question is what Franklin County is willing to do to change its demography.

Open house in Danville

Cardinal is kicking off a series of open houses around our coverage area. On Tuesday, we’ll be in Danville at Crema & Vine from 2 p.m. to 4 p.m. If you’re in the area, come by to meet some of the Cardinal team.