The year 2026 marks the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Cardinal News has embarked on a three-year project to tell the little-known stories of Virginia’s role in the march to independence. As part of this, I will be writing monthly columns about the politics of the era, written the same way I’d write them today. The events described here took place in May 1765.

This project is supported, in part, by a grant from the Virginia American Revolution 250 Commission. You can sign up to receive a free monthly newsletter with updates.

Virginia has now put itself crosswise with the crown, all thanks to a tiny stamp — and a big objection from a brand-new legislator who seems destined to make more trouble for London.

There were few members in the chamber in Williamsburg when newly elected Patrick Henry of Louisa County introduced his provocative “Virginia Resolves” against the Stamp Act that the British parliament has imposed on the colonies, but the House of Burgesses passed it anyway — temporarily, at least.

The subsequent repeal of the most confrontational measure may not matter; the colonial press has trumpeted the initial passage without much regard for the facts that followed. That detail may not matter as much as the principle that the legislature briefly declared — that Parliament in London has no right to tax its colonists — and the inflammatory language that Henry used to make his points.

The 29-year-old Henry was a legislator for just nine days when he prompted House Speaker John Robinson to accuse him of promoting treason, to which Henry boldly responded: “If this be treason, make the most of it.”

While Henry might be new in Williamsburg, this isn’t the first time he’s excited a crowd to shout “Treason!” against him. You’ll recall that about a year and a half ago, in December 1763, his legal arguments against royal authority in the so-called “Parson’s Cause” case in Hanover County over back pay for Anglican ministers elicited cries of “Treason!” in the courtroom — but also produced a verdict in favor of his anti-clerical clients. Not long afterward, Henry moved next door to Louisa County, got himself elected to an open seat in the House of Burgesses, and has now stirred up that body the same way he did the Hanover courtroom. This is clearly a man to keep our eyes on.

For now, let’s review the events that have brought us to this point, because they may wind up being more portentous than the meteoric rise of a new politician.

The French and Indian War has left Britain in debt.

What the Stamp Act covers

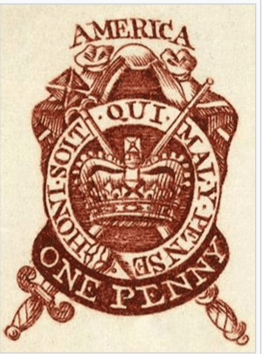

The Stamp Act requires an official stamp be affixed to a wide variety of documents. Filing a deed for land? You have to pay for a stamp. Getting married? You have to pay for a stamp. Recording a will? You have to pay for a stamp. Any kind of legal contract requires a stamp. So do newspapers and pamphlets. Printers, quite naturally, will simply pass those costs on to readers, so London is making it more expensive for colonists to stay abreast of news. Even playing cards and dice require a stamp, so London is now taxing our idle pleasures.

More worrisome for some is the requirement that stamps be affixed to law licenses and diplomas. Why does that matter, if most of us are not lawyers or college students? Some see this as an attempt by London to stifle the growth of a professional class in the colonies. They make the case that Britain would prefer to keep its colonists simply as fur-trappers and farmers to supply the mother country with goods; any attempt for the colonies to create their own economies runs afoul of London’s economic goals.

Worse yet, the Stamp Act requires that the stamps be paid for in hard currency, which is difficult to come by, and not the far more common paper money that circulates in the colonies.

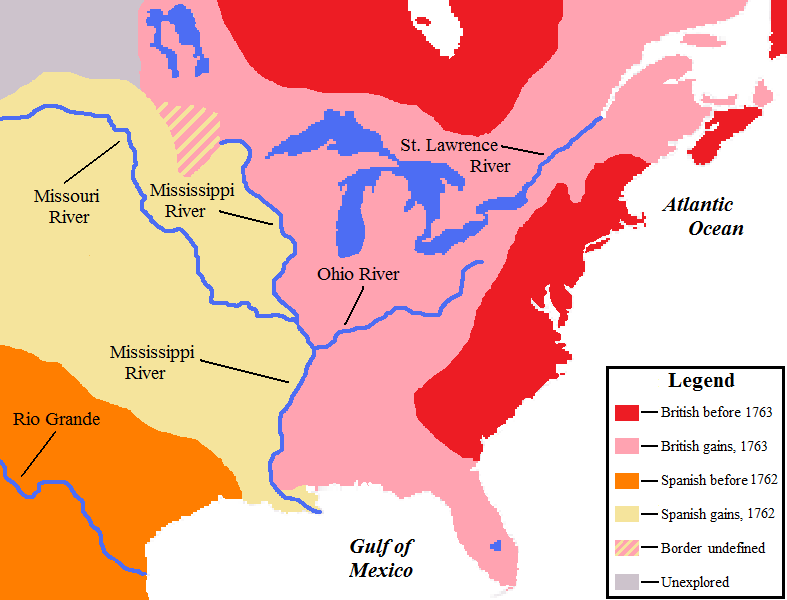

Those of us on this side of the Atlantic, particularly those of us living out here on the frontier — I write these words from Miller’s Mill in Augusta County (Editor’s note: modern-day Fincastle in Botetourt County) — think of Britain as a wealthy nation but that’s not how it sees itself. By some estimates, the recent war cost the British treasury 70 million pounds and doubled the national debt to 140 million pounds. When people say that wars are costly in terms of blood and treasure, this is the treasure part. From our point of view here in North America, that war ended with a tremendous victory: France had to cede its Quebec province to the British. Before the war, the French had designs on the Ohio country and all the land around the Great Lakes. Now the prospect of French expansion into the interior of the continent is eliminated, and Britain holds claim to lands all the way to the distant Mississippi River. True, there are still Native American tribes who vigorously dispute those claims, but those tribes no longer threaten Virginia.

However, ever since the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1763, Britain and its colonies have had very different views about how to proceed. Virginians, in particular, want to push westward and settle those lands. The king, though, is more intent on holding down security costs than helping his colonial subjects enrich themselves with land. He imposed his Proclamation of 1763, which forbids settlement west of an arbitrary line through the mountains. I’ve written before about how that proclamation has united two groups with often opposing views of the world: the land speculators among the eastern gentry with the poor farmers looking for more land. Now Britain has imposed the reviled Stamp Act on the colonies as a way to raise revenue, further provoking tensions. Irony: The conclusion of the late war should have brought about a window of opportunity and euphoria; instead, it’s only provoked conflict between Britain and its colonies.

London and its colonies disagree over who should pay for their defense.

Indeed, there’s an even deeper dispute over how much defense the colonies actually need. London was always more worried about the French than the colonists were. Colonists didn’t want the French moving into the Ohio country, but we never worried about them actually invading the British colonies. In any case, Britain has now decided to do something it’s never done before — to station a standing army in the colonies. Why do we need a standing army when the French have been defeated and chased from North America? The British still see a threat from the French-speaking Quebeckers who are now under a British flag and the Spanish who own lands west of the Mississippi, but its colonists do not. While some of the soldiers are out on the frontier fighting the native tribes, most of these British soldiers seem to be lolling about in seaboard cities, from what we can tell.

Furthermore, there aren’t sufficient barracks for all these soldiers. Parliament has passed the Quartering Act that requires colonists to provide lodging for these soldiers in inns, ale houses and even the public houses of those who serve food to visitors. (Editor’s note: This is what led to the Third Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which says “No Soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the Owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.”) Some colonists have resented this Quartering Act as much as they have the more infamous Stamp Act. There have been dark suggestions that the only reason the British are keeping an army here at all is to provide patronage for certain well-connected career officers who otherwise would have no jobs at home after the war — except now London is trying to foist those costs onto us. The Massachusetts lawyer John Adams has summed things this way: “Revenue is still demanded from America, and appropriated to the maintenance of swarms of officers and pensioners in idleness and luxury.”

London sees the colonies as easier to tax than subjects in Britain.

Prime Minister Bute is gone — remember the short-lived administration of John Stuart, Third Earl of Bute, who lasted less than a year from 1762-1763 — but the memory of his tenure is seared into British memory. He was initially popular because he presided over the end of what London calls the Seven Years’ War (our French and Indian War was only part of a global conflict) but soon became unpopular because he tried to make the British pay down that war debt. He proposed a tax on cider in Britain, which incited rioting among the cider-loving populace. Those riots helped bring down Bute’s government. His successor, George Grenville, pushed through the measure anyway but then quickly resolved to shift future taxation to the distant colonies, which is what has brought us the Quartering Act, which requires colonists to pay for soldiers, and the Stamp Act, which creates a wider range of taxes. We are farther away, so apparently any rioting we engage in won’t matter as much. There’s also this salient fact: We colonists don’t get to vote for Parliament, the way some of those rioters in Britain do. As Shakespeare wrote in “Hamlet”: “Aye, there’s the rub.”

Who has the right to tax colonists?

While some are focused on the practicalities of the stamp tax (which applies even to playing cards!), the most serious objection is a philosophical one. That’s why what Henry did in the House of Burgesses is so important — he has called the question clearer than anyone else.

Let’s review: When news arrived in Virginia that Parliament was considering the Stamp Act, the House of Burgesses instructed its agent in London, Edward Montague, to oppose the measure. So did legislatures in other colonies. Some in the colonies raised an alarm, but let’s face it, newspapers are always raising an alarm about something. Politicians were often more muted. Even the noted Benjamin Franklin, who represents Pennsylvania in London, did not see this storm coming — he actually recommended some possible tax collectors to the Grenville administration. That was surprising because as far back as 1754 Franklin had more quietly suggested what Henry has now done more loudly: “It is suppos’d an undoubted Right of Englishmen not to be taxed but by their own Consent given thro’ their Representatives,” Franklin wrote then. “The Colonies have no Representatives in Parliament.”

In Virginia, the House of Burgesses seemed so little concerned and saw so little business to be conducted that many of the legislators simply went home. The House remained in session, however. To preserve a quorum, the more eastern members of the legislature instructed its western members to stay in Williamsburg. (This highlights a profound regional divide in Virginia that might grow only wider in coming years, but I digress.) One of those western-most members was a new legislator who had just arrived, fresh from winning a special election to fill a vacancy in Louisa County: the aforementioned Henry. This proved to be a mistake by those in the eastern gentry with less radical tendencies and an opportunity for the young — and rash — Henry.

Henry rode into Williamsburg on May 20 to take his seat. By May 28, only 39 of the 116 Burgesses were still in town, the lowest attendance ever seen. That day, though, a ship arrived bearing news from Montague in London that Parliament had, indeed, approved the Stamp Act two months earlier. Henry swung into action. The next day he introduced his five resolutions collectively known as the Virginia Resolves. They never mention the Stamp Act at all. Rather, they lay out the philosophical arguments that could, in theory, if carried to the extreme, break the bonds between Virginia and the British Parliament.

The first asserted that “the first adventurers and settlers of His Majesty’s colony and dominion of Virginia” brought with them “all the liberties, privileges, franchises, and immunities that have at any time been held, enjoyed, and possessed by the people of Great Britain.”

The second said that principle was reiterated by two royal charters for the colony.

The third asserted that the principle that only an elected legislature can tax the people is “the distinguishing characteristic of British freedom.”

The fourth said this principle “has never been forfeited or yielded up, but has been constantly recognized by the kings and people of Great Britain.”

That civics lesson led up to the more controversial fifth resolution: that only the elected legislature of Virginia has the power to tax Virginians and that “every Attempt to vest such Power in any person or persons whatsoever other than the General Assembly aforesaid has a manifest Tendency to destroy British as well as American Freedom.”

Other dispatches in this series

Dispatch from 1765: Augusta County mob murders Cherokees, defies royal authority.

Dispatch from 1763: Despite cries of ‘treason!,’ Hanover County jury delivers rebuke to the church – and the crown. (The court case that made Patrick Henry a celebrity.)

Dispatch from 1763: King’s proclamation has united often opposing factions in Virginia. (Opposition to the king’s proclamation forbidding western settlement.)

In other words, the Parliament in London can’t tax Virginia — or, by implication, any of the North American colonies — and therefore the Stamp Act or any other is invalid. This stands in direct contradiction not simply to British power but British philosophy — that the colonists are “virtually” represented in Parliament in the same way that those in Britain who can’t vote (such as men who don’t hold property, or women) are “virtually” represented. These are two diametrically opposed theories of government.

While Henry acted quickly, he did not act alone. He worked in concert with two other legislators, John Fleming of Cumberland County and George Johnston of Fairfax County.

Henry and his cohort benefited from the poor attendance in the legislature. I mentioned the long-standing political divide between those in the tidewater lowlands and the more western legislators west of the fall line. Those easternmost legislators tend to be the most cautious; those from the west are often seen much like their country itself, wild and raucous — and now, with the arrival of Henry, radical.

Henry seems eager to cultivate that image. He’s said to have arrived in Williamsburg not in finery but in “very coarse apparel” and did not make a good impression on the establishment figures inhabiting the legislature. They recall “an ill-dressed young man sauntering in the lobby” whom they didn’t know. They soon would.

The absence of most of the eastern legislators gave an advantage to Henry and other westerners.

Henry’s first four resolutions passed 22-17, a surprisingly thin margin for pronouncements that are really just recitations of history. Have we come to the point that now we can’t even agree on historical facts? Perhaps the dissenters saw where Henry was headed with his fifth resolution. That’s the one that set off the most debate. Here is where the freshman legislator showed off the oratorical skills that have helped him win over juries.

There is some dispute about what, exactly, Henry said. There is no written record of remarks, so we must rely on secondhand accounts. By some of those, Henry rose “in a voice of thunder and with the look of a god” as he railed against not just Parliament but, most shockingly, King George III himself — and referenced the assassinations and executions of dictators through history: “Tarquin and Caesar had each his Brutus, Charles the First his Cromwell and George the Third —” Henry paused for dramatic effect and was shouted down by Speaker Robinson: “Treason!” Others in the chamber joined with their own cries of “Treason!” Henry seemed unconcerned. He is said to have stared right at the speaker and continued: “— may profit from their example.” Henry then added, defiantly: “If this be treason, make the most of it.”

Two students from the College of William & Mary were standing in a doorway, witnessing the drama unfold. They don’t remember the invocations of Caesar and Cromwell but do confirm that the speech was incendiary. Thomas Jefferson of Albemarle County writes that Henry was “all tongue.” Jefferson did not seem particularly impressed by Henry: “He said the strongest things in the finest language, but without logic, without arrangement.” John Tyler of Charles City County (Editor’s note: He was later governor of Virginia and father of future President John Tyler) was more sympathetic. He called the session one of “the trying moments which is decisive of character.”

Henry’s fifth resolution passed 20-19. Burgess Peyton Randolph of Williamsburg stormed out of the chamber, declaring: “By God, I would have given one hundred guineas for a single vote.”

Curiously, Henry did not stick around. He left town the next day, again dressed in frontier garb. It’s unclear whether Henry’s fashion choices are personal preference or a political statement. He’s hardly a rustic; his father is a judge in Hanover County, his mother is said to be “woman of recognized mental power and an unusual command of language” who is said to have schooled her son by questioning him about the sermons they attended at a Presbyterian church. In any case, that’s not what matters here. What matters is this: Alarmed by what had just happened, more cautious burgesses rushed back to Williamsburg and didn’t just repeal that controversial fifth resolution, they expunged it from the record altogether — an official rewriting of history, as it were. Furthermore, Gov. Francis Fauquier forbade the colony’s official newspaper, the Virginia Gazette, from publishing any reference to the resolution. Fortunately, Ye Olde Cardinal News does not depend on any government subsidy; we rely instead on the generosity of our readers, so we are free to relay this news.

The power of the press has amplified Henry’s resolution.

The colonial press is noted for its vigor, but not always for its accuracy. Newspapers through the colonies — starting with the Newport Mercury in Rhode Island — began reporting that Virginia had adopted a resolution declaring that Parliament had no power to tax the colonies. They either didn’t get word, or didn’t care, that Virginia had quickly done away with that resolution. Furthermore, some papers printed two more resolutions that Virginia never passed — and which Henry may never have actually written. The supposed sixth resolution declared that colonies “are not bound to yield obedience to any law or ordinance whatsoever” that their own legislature didn’t pass. The seventh, more radical yet, declared anyone asserting that some other body than the House of Burgesses had the right to tax Virginians — i.e., Parliament — “shall be deemed an enemy.”

Some newspapers that published those last two resolutions didn’t report that they’d never been voted on, making Virginia’s action look more radical than it really was. We’re told now that other colonies are contemplating their own resolutions against the Stamp Act, and also plan to assert the argument of “no taxation without representation.” As a matter of law, Virginia’s repudiation of Parliament’s right to tax Virginians lasted only a day or so. However, no one expects this to be the last we’ve heard of this proposition. This argument will likely go on as long as the Stamp Act remains in force — or, perhaps even longer.

Breaking news: Virginia voters deliver rebuke to governor, British Parliament

Gov. Fauquier thought he’d quell popular dissent by dissolving the House of Burgesses and calling new elections, hoping calmer heads would prevail in the election. Instead, just the opposite happened: The election saw more moderate members of the legislature voted out, replaced by anti-Stamp Act members. Faced with this unpleasant political reality, the governor has responded by not calling the newly elected legislature into session. What we need is a system of government where the legislature meets regularly, whether the chief executive wants it to or not.

Sources consulted include “Forced Founders: Indians, Debtors, Slaves and the Making of the American Revolution in Virginia” by Woody Holton, “Virginia: The New Dominion” by Virginius Dabney, and Encyclopedia Virginia.