Want to read more on Virginia’s demographic trends? We’ve collected all our demographic coverage in one place.

Every governor I’ve ever known has compared Virginia to North Carolina. That’s our big economic rival.

I recently wrote about some new Census Bureau statistics on the growth of remote workers from pre-pandemic levels. Short version: They’re up, they’re up almost everywhere, and in some places they’re up a lot.

Today, let’s look at that data a different way — through the prism of how Virginia compares to North Carolina.

Let’s also assume that remote workers are a good thing. I’ll admit to some bias, since I’m a remote worker. Donors can rest assured that we’re a frugal operation that’s not spending your valued contributions on a fancy office suite. Those who own downtown office space may not feel so cheery about remote workers. However, I’m looking at this through the prism of rural economic development. Most rural counties want and need more people. Remote work is a way to either keep them there or attract them there. Granted, remote workers don’t bring a tax base for machine and tools taxes, but neither are they requiring industrial-level water and sewer. They do, though, bring their incomes that can be spent locally.

With those stipulations, let’s see what we can find:

Virginia beats North Carolina

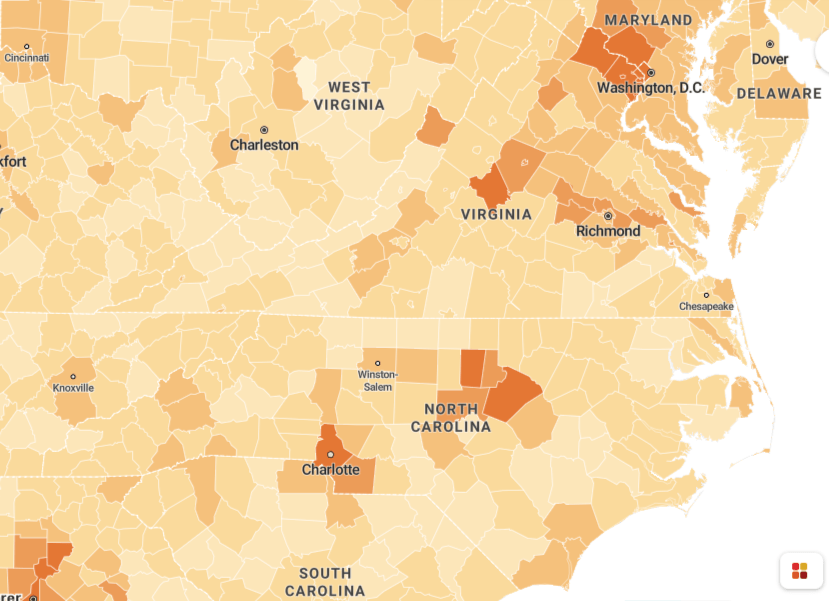

Let’s go to the bottom line first. Before the pandemic, North Carolina had a bigger share of its workforce working remotely than Virginia did: 6.7% of the North Carolina workforce, one of the highest percentages in the nation, compared to 5.8% for Virginia.

All that’s changed. Now Virginia has 18.2% of its workforce working remotely compared to 16.8% for North Carolina. North Carolina has more overall because it’s a more populous state, but on a percentage basis, Virginia is more invested in remote work.

That’s mostly because of the huge shift toward remote work in Northern Virginia, which has exceeded what has happened around North Carolina’s biggest metro areas in Raleigh and Charlotte. In Wake County, North Carolina (Raleigh), 22.36% of workers are now listed as remote workers. In Orange County, North Carolina (Hillsborough), 21.72%. In Mecklenburg County, North Carolina (Charlotte), 21.52%. Those are North Carolina’s three localities with the biggest share of remote workers, but the top one would rank fourth if it were in Virginia. In our Arlington County, 26.9% of workers working remotely in Falls Church, 26.81%, In Loudoun County, 23.51%; in Alexandria, 22.11%; in Fairfax County, 21.69%.

Of course, we do have this advantage: Northern Virginia has one of the highest concentrations of remote workers in the country. The numbers in the two biggest North Carolina metros are big, but ours are a little bigger.

Let’s dive deeper, then, to see how different parts of Virginia stack up against comparable locations in North Carolina.

The Roanoke Valley ranks behind Asheville

Roanoke has long had an inferiority complex about the largest city on the other end of the Blue Ridge Parkway. Ideally, beating Asheville for the Deschutes Brewery cured Roanoke of that, even though the brewery wound up never materializing. So how does the Roanoke Valley compare with Asheville as a destination for remote workers? Sorry, Asheville wins this comparison, although the Roanoke Valley is in the game.

Buncombe County, North Carolina — which under the Tar Heel system of governance includes Ashville — has 14.41% of its workforce working remotely. Virginia’s system of independent cities means we have to look separately at different localities. Roanoke County has the highest remote worker percentage in the Roanoke Valley, at 12.5%, with the city of Roanoke coming in at 9.7% and Salem at 8.51%.

The percentage for Roanoke County competes well with Buncombe County, but if you add up the total number of remote workers, the Roanoke Valley falls short. Buncombe County has 18,744. The Roanoke Valley has 11,374 — that’s 5,810 in Roanoke County, 4,512 in Roanoke, and 1,052 in Salem.

You’ll notice I’m leaving out Botetourt County. That’s so we can avoid double-counting when I compare Buncombe’s next-door neighbor, Madison County, with Botetourt County. Madison County has a slightly higher percentage (12.4%) than Botetourt County (10.15%), but Botetourt County has more remote workers — 1,607 to Madison’s 1,159.

If you step back and look more broadly, the general Asheville area has almost twice as many remote workers as the Roanoke area does. However, the number of remote workers in and around Roanoke is growing at a faster rate than in and around Asheville (Buncombe County was up 47.7% from 2019 to 2022, while Roanoke County was up 144.6% and Roanoke was up 124%).

If this makes anyone in the Roanoke Valley feel better, consider this comparison with the North Carolina Triad region. Our Roanoke County counts a workforce that’s 12.5% remote; Forsyth County, North Carolina (Winston-Salem) is at 10.57%. Guilford County, North Carolina (Greensboro) is at 10.25%.

Some of Virginia’s Blue Ridge Parkway counties top North Carolina’s parkway counties, some don’t.

Let’s look beyond the Roanoke Valley and the Asheville area to see how other counties along the Blue Ridge Parkway do in attracting remote workers. Between Asheville and the Virginia state line, four of the five North Carolina counties that the parkway runs through have between 7% and 9% of their workforce working remotely. The exception is Mitchell County, with 5%.

Virginia has four parkway counties south of the Roanoke Valley. Floyd County (10.14%) and Patrick County (9.74%) top their North Carolina counterparts. Two, though, don’t. Grayson County comes in at 4.8% while Carroll County comes in at just 3.47%.

The North Carolina counties are more consistent with their numbers. Virginia’s are more scattered. I’m not sure how fair it is to compare Virginia’s parkway counties north of Roanoke because the geography and demography changes so much, so I’ll stick to just the counties between Asheville and Roanoke.

The Chesapeake Bay tops the Outer Banks

Some of Virginia’s counties along the Chesapeake Bay were hotspots for remote workers even before the pandemic. Now they’re more so. The Outer Banks can’t compare. Middlesex County now has 16.97% of its workforce working remotely; other counties along the eastern side of the bay are generally in the mid-teens, with Mathews County at 14.5%, Lancaster County at 13.6%, Northumberland County at 13.2%.

By contrast, Dare County, North Carolina, comes in at 12.9%. New Hanover County, North Carolina, which includes Wilmington, comes in at 14.9%. It’s the only coastal county in North Carolina that tops most of our coastal counties.

Localities that demographers call “rural resort” communities have become magnets for remote workers, but our waterside counties generally beat North Carolina’s. Take that.

Virginia has an opportunity to pitch itself as a remote work capital

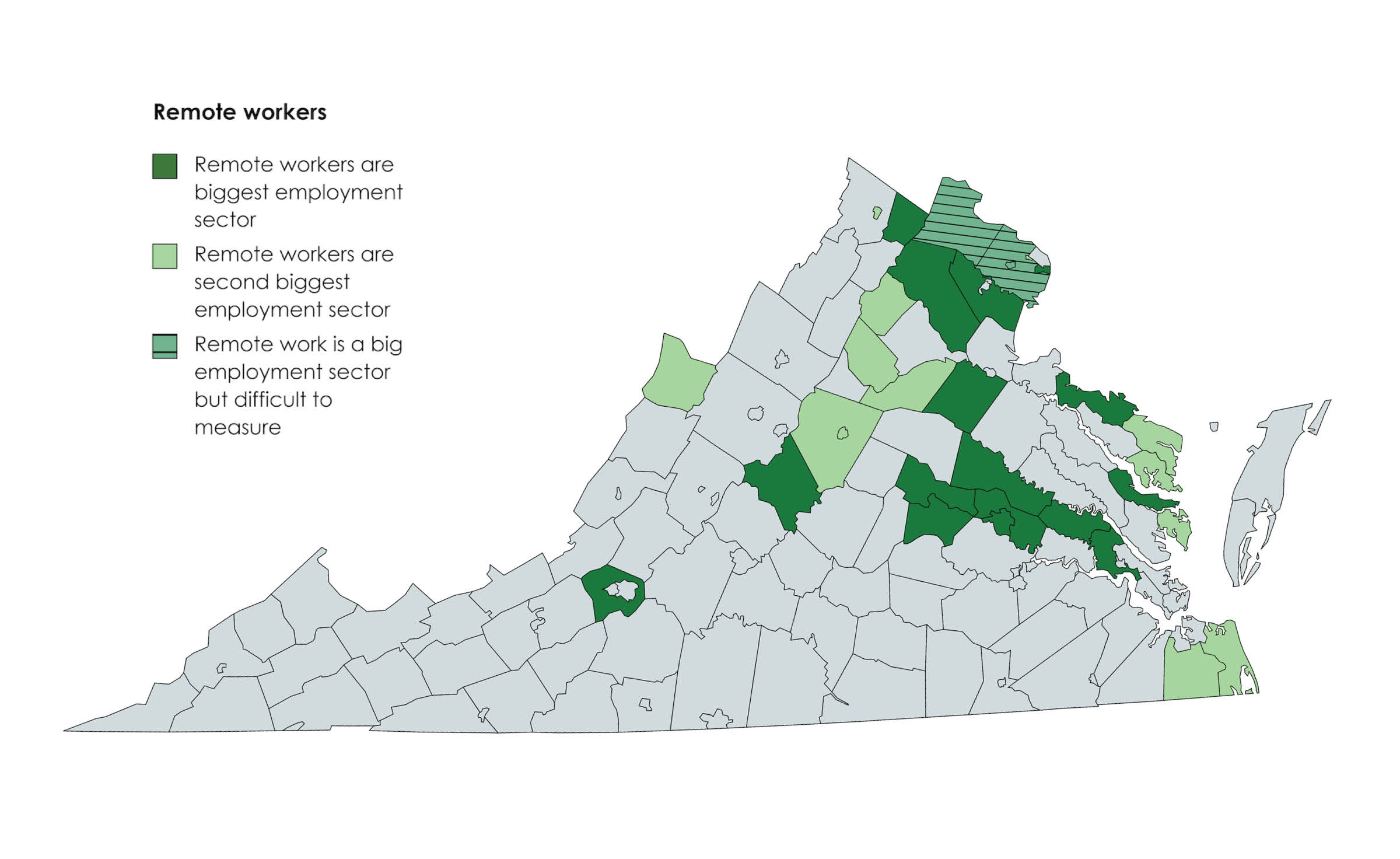

Here’s where all this is leading: These Census Bureau stats help show some interesting disparities, and not just the disparity between the large concentration of remote workers in Northern Virginia and the smaller number elsewhere, but disparities between certain rural areas. When we step back and look more broadly, we see some curious gaps.

Why are Floyd County and Patrick County becoming magnets for remote workers, but Carroll County, Galax and Grayson County aren’t? I don’t think it’s lack of broadband, because Broadbandnow.com shows Patrick County has a lower percentage of broadband coverage than Carroll and Grayson.

It’s not my place to tell counties where I don’t live what their economic development strategies should be, but it is curious to me that Carroll and Grayson, two of the most beautiful counties in the state, have benefited so little from remote workers when some of their neighbors have twice as many. The Census Bureau even shows that the raw number of remote workers has declined in Carroll County (from 433 to 418) while next door in Patrick County it’s nearly tripled (from 242 to 702). Galax also declined, from 168 to 127.

All three Census Bureau measures for Carroll, Galax and Grayson — percentage of workforce working remotely, the number of remote workers, and the percentage change in their numbers — are out of step with not just many of their neighbors in Virginia but also their counterparts across the line in North Carolina. Are those counties missing an economic development opportunity?