Want to read more on Virginia’s demographic trends? We’ve collected all our demographic coverage in one place.

Bedford County has now joined the list of localities that are looking at closing schools.

Franklin County has floated the prospect of closing two elementary schools this summer.

Lynchburg has already moved to close one elementary school and possibly close another.

Once again, we must ask the question: Why is this happening, especially in a county that’s been gaining population for half a century, and a county that has been one of the fastest-growing in the state?

The answer, once again, comes back to the same one we’ve had in Lynchburg and Franklin County: demographics. Specifically, a declining birth rate.

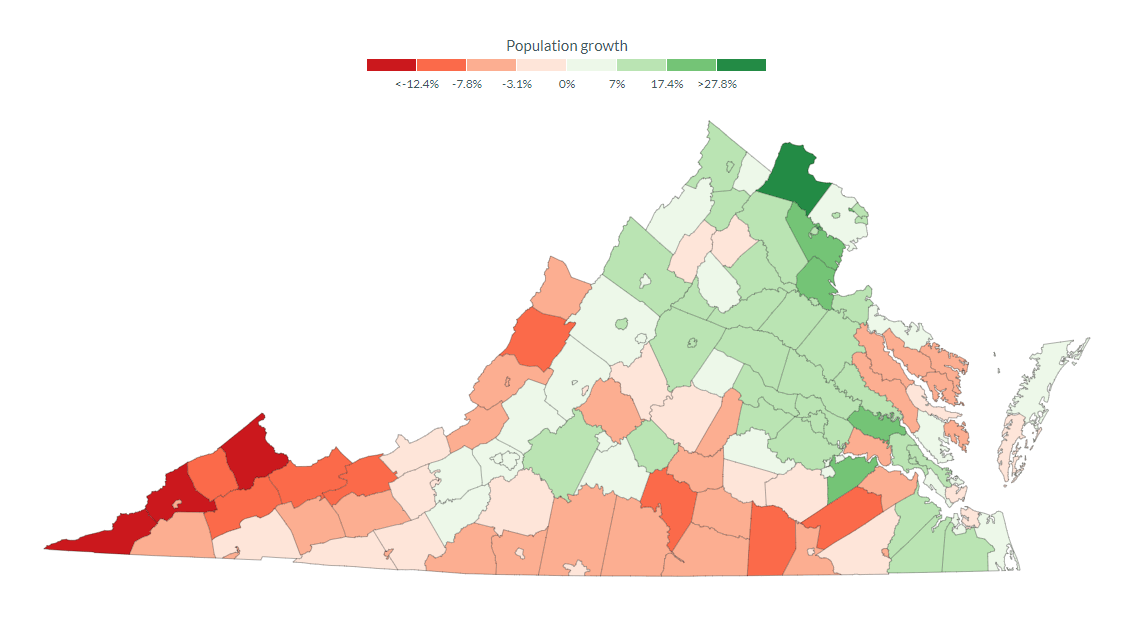

Bedford’s population has grown 21% since 2000 (this accounts for the consolidation with the former city of Bedford) but its school enrollment has declined 16%, according to the Virginia Department of Education. Bedford’s enrollment is projected to decline further even as the population continues to increase, according to recent figures from the Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service at the University of Virginia.

The migration of public school students to private schools and home schools accounts for some of this decline, but not all. The basic driver is that Bedford’s population may be growing, but it’s aging, and those who are having children aren’t having as many as they used to. This isn’t the first time that Bedford has closed schools. Body Camp Elementary and Thaxton Elementary were shuttered in 2015. Now Stewartsville Elementary has been singled out for closing as part of four “efficiency” options before the school board. There are some specific factors that put Stewartsville, as opposed to some other school, on the chopping block, but before we get to that, let’s review the overall trends because they are ones that touch places beyond Bedford.

Bedford’s population peaked in 1890, then, like many rural counties, it saw its population decline in fits and starts as the industrial age drew people away from agricultural areas. A high of 31,213 in 1890 fell to a population of 26,738 in 1970. Since then, Bedford’s population has risen rapidly — to 79,462 in the most recent census, with a population of 80,759 in the most recent Weldon Cooper estimates. For five straight decades, Bedford has logged double-digit population growth, clocking in at 15.7% in the 2020 census. That made Bedford the fastest-growing locality west of the urban crescent — and faster-growing than even many of the localities in the urban crescent.

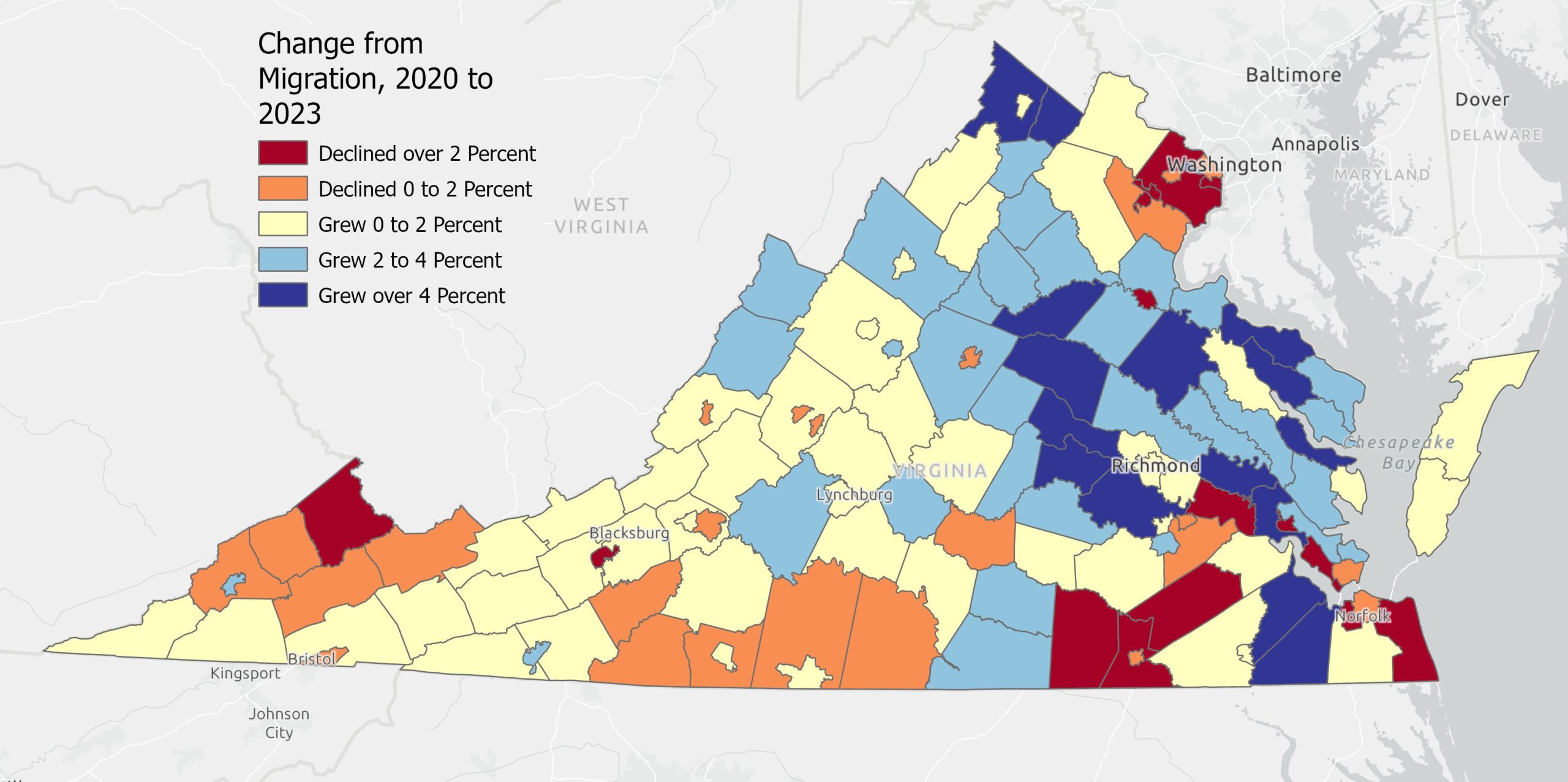

Three things have historically driven Bedford’s growth: Smith Mountain Lake from the south, Lynchburg’s suburban growth from the east and Roanoke’s exurban growth from the west, with the first two of those being the most important. Now there’s a fourth one: New population figures show growth in many rural areas since the pandemic so in the case of Bedford, that Zoom-era migration gets layered over the other population drivers.

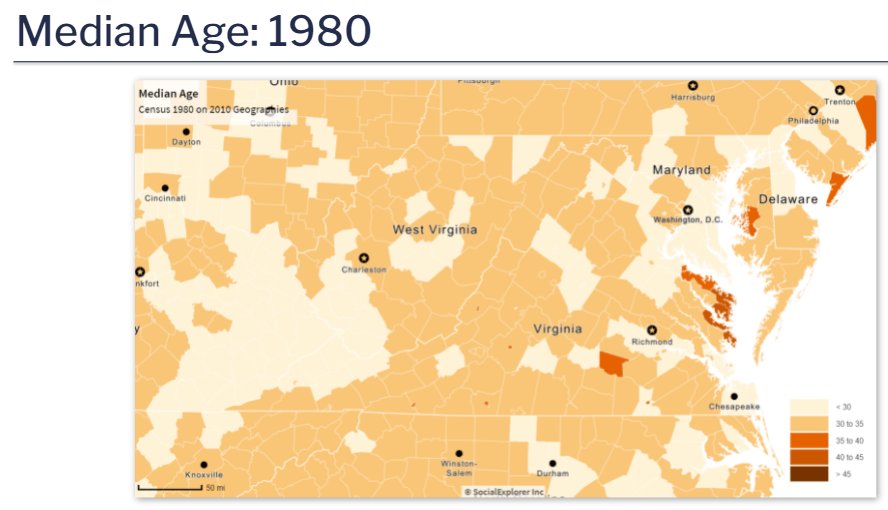

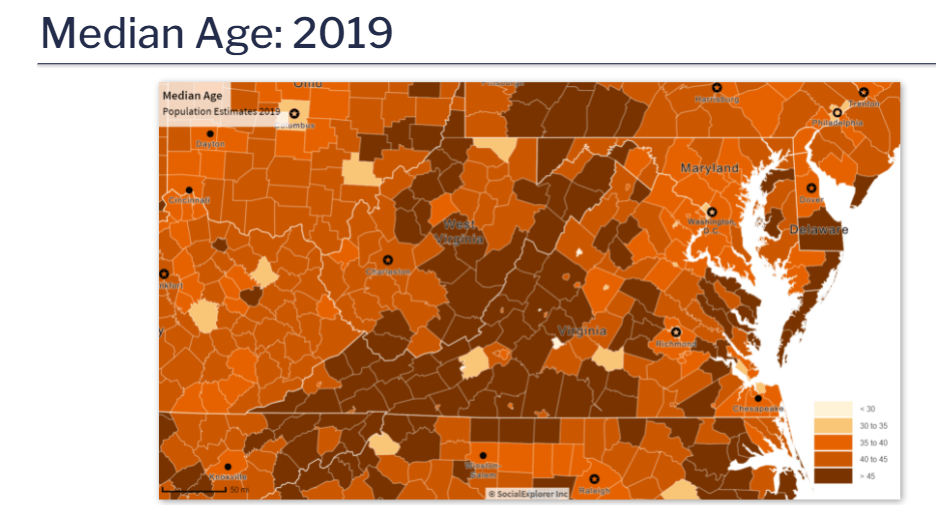

However, Bedford has also grown substantially older. Some of that is the general aging of our society, some of that is due to retirees moving to Smith Mountain Lake or rural areas in general. In 1980, Bedford County had a median age of 31.8, just slightly older than the national median of 30. By 2021, Bedford’s median age was 47.8, nearly a decade older than the national median age of 38.8.

Even if the nation’s birth rate weren’t declining, we shouldn’t be surprised that an aging population has left Bedford with fewer students. However, the nation’s birth rate is declining, so Bedford finds itself hit two ways. Given those two trends — an aging population, and a declining birth rate — Bedford would have to see even more population growth than it’s presently seeing if it wanted simply to maintain the students it has (8,837) rather than see its school enrollment decline to a projected 8,603 in 2028-29. I suspect most in Bedford would like to see the county retain its rural character — but, demographically speaking, if they want to keep their school population big enough to keep all the schools open, they’ll need more development.

Bedford’s population growth is also not evenly distributed, which causes a particular problem for Stewartsville. The census tracts that overlap the Stewartsville school zone contain a population that’s older than much of an already old Bedford County population — in one, the median age is 51. It’s also a population that, not surprisingly, is not having many babies. In all of the Stewartsville-related census tracts, the birth rate is lower than in Bedford as a whole. How low? About one-quarter of Bedford’s overall birth rate in one tract, topping out at two-thirds in another. This is why Stewartsville Elementary is at only 56% capacity. Meanwhile, three schools in the Forest area are at or near capacity.

The demographic fix is straightforward: The Stewartsville section of the county needs more families with children. Who in Stewartsville would like to see more development to help attract those young families?

The Stewartsville situation is complicated by the fact that its school is 112 years old. Superintendent Marc Bergin has said it would cost $20 million to $30 million to renovate the school.

Are Bedford taxpayers in a mood to spend that kind of money to renovate a school in a part of the county that, relatively speaking, doesn’t have many students?

Bedford may find ways to stave off the closure of Stewartsville Elementary for a while, but certain facts can’t be negotiated away: The building is old and is said to need a new roof and HVAC system.

This isn’t unique, either. More than a decade ago, as Gov. Bob McDonnell was leaving office, his administration calculated that Virginia had about $25 billion worth of school construction needs. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ inflation calculator, that would be more than $33 billion today.

School construction has historically been a local responsibility, not a state one, although there have been periodic attempts to change that, particularly as the costs soar higher than rural localities can afford. In 2019, state Sen. Bill Stanley, R-Franklin County, pushed for an advisory referendum on a $4 billion statewide bond issue for school construction. That was defeated 14-2 by a bipartisan coalition in the Senate Finance Committee.

In 2022, the General Assembly approved a school construction fund — pushed by Del. Israel O’Quinn, R-Washington County, and then-state Sen. (now U.S. Rep.) Jennifer McClellan, D-Richmond — to create a $1.25 billion school construction fund that, when coupled with local spending, could leverage up to $3.1 billion in school construction. That was historic in scope, but $3.1 billion isn’t $25 billion or $33 billion — and it also requires some local participation. Again, is Bedford County willing to spend that kind of money?

It could — if it wanted to raise taxes. Bedford’s tax rate of 41 cents per $100 of assessed value is one of the lowest around. In Franklin County, the rate is 61 cents. In Botetourt County, it’s 79 cents. In Lynchburg, it’s 89 cents. I doubt if anyone in Bedford wants to see their taxes raised, but this is just the math. Of course, raising the tax rate would also make Bedford a more expensive place to live, and that would likely make it harder for the county to attract the younger adults it needs, particularly in the Stewartsville school zone, and the larger Staunton River High School school zone.

There is potentially another option. There’s legislation moving through the General Assembly — sponsored by Del. Sam Rasoul, D-Roanoke, in the House and state Sen. Jeremy McPike, D-Prince William County in the Senate — that would give localities the power to hold referendums on whether to raise the local sales tax, with the revenue going to school construction.

All the legislators representing Bedford — Dels. Tim Griffin, R-Bedford County, and Eric Zehr, R-Campbell County, in the House, and state Sen. Mark Peake, R-Lynchburg — voted against those bills.

The advantage of such a sales tax is that some of the cost is borne by people passing through the county, but there are disadvantages as well. Some don’t like that the sales tax is a regressive tax. Some don’t like opening the door to any tax increases. Some don’t like the idea that this would give Virginia a patchwork of tax rates (although nine localities already have this power, so we already have a patchwork). There may be lots of reasons to oppose the local sales tax measure, but if it gets signed into law, that would be an option Bedford could consider. Yes, Bedford is a conservative county, but it’s notable that so are seven of the nine localities that have already passed such referendums — and, based on the last gubernatorial election, Bedford is not quite as conservative as Patrick County, which approved such a tax.

These are the demographics that have put Stewartsville Elementary on the edge of closure and these are the policy choices that could save it — if enough people in Bedford County are willing to pay that price.

Town hall meetings

The Bedford County School Board has scheduled three community meetings to receive public input on the superintendent search. A statement from Bedford County says school board members “would also welcome feedback at these sessions regarding the four efficiency options” — all of which include the closure of Stewartsville Elementary. All the meetings are from 4:30 to 8 p.m.

Thursday, Feb. 29: Liberty High School

Tuesday, March 5: Jefferson Forest High School

Tuesday, March 19: Staunton River High School

Cardinal News is holding an open house Wednesday in Blacksburg from 2 p.m. to 4 p.m. Come meet some of the Cardinal team. We have other open houses coming up in Bristol and Lynchburg.