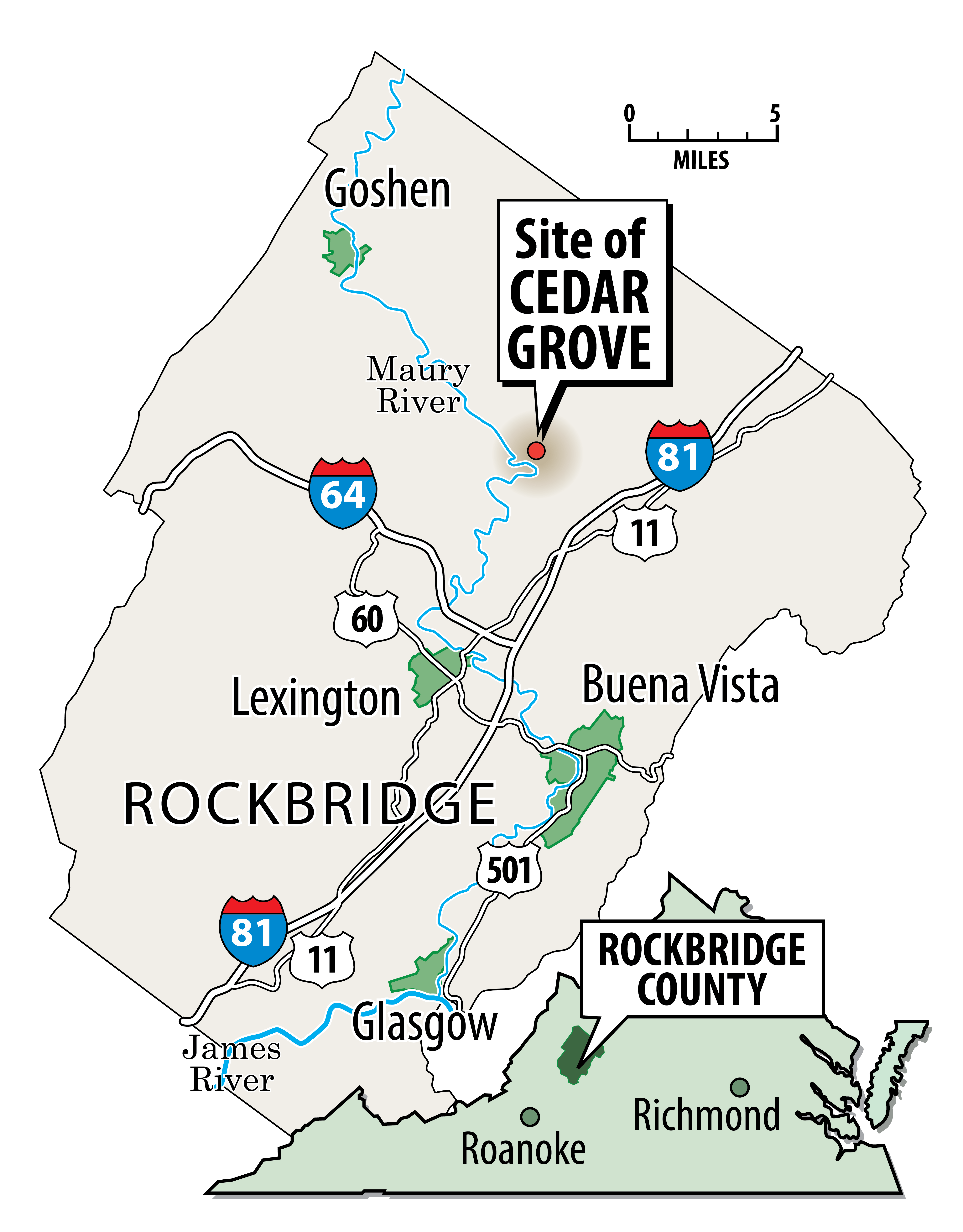

Southeast of Rockbridge Baths and southwest of Brownsburg, where Virginia 39 curves and runs parallel to the Maury River, there once was a town called Cedar Grove.

No buildings remain from the community, which reached its heyday between 1820 and 1860 before sinking into obscurity after the Civil War, according to historical records and project sponsor David Hopkins. Larry Spurgeon, president of the Rockbridge Historical Society’s board of directors, last found mention of Cedar Grove in records from the early 1900s, such as in a 1906 obituary published in the Lexington News-Gazette.

Once, there stood a saw mill, a post office, a boat yard, mercantile stores, a blacksmith and warehouses, among other fixtures, according to Hopkins’ review of historical records and maps. The community of Cedar Grove submitted a petition to become a voting precinct in 1852. Sixty men signed on.

Unlike other small historical communities in Rockbridge County, such as Rockbridge Baths and Brownsburg, Cedar Grove no longer has a place on the map, Spurgeon said. The only remnant left is Cedar Grove Branch, a creek that intersects with the Maury River near the site of the former town.

Now, a state highway marker sponsored by Hopkins and his wife, Diana, aims to clue residents into the story of Cedar Grove. The couple has lived in a home at the site of the old town since 2009.

The approved text for the marker, which will likely go up in the next year, tells the brief story of Cedar Grove. The community was the highest point of small-boat navigation on the Maury River, then called the North River, around the 1830s. Free and enslaved men rowed flat-bottomed, double-sided boats called batteaux to transport iron from local forges to as far as Richmond.

“The decline of the local iron industry later in the 1800s and disuse of the river for transportation led to the town’s abandonment,” the final line of the marker reads.

Cedar Grove’s patchy history

The Hopkins’ fascination with Cedar Grove started when a history-loving brother-in-law encouraged the couple to look into the history of their riverfront home. In 2022, the couple began applying for a highway marker.

In 2017, the Hopkins began assembling a binder filled with the few historical traces of Cedar Grove: deed transfers, wills, for-sale notices, obituaries, a voting petition submitted to Virginia’s General Assembly. Some 20th-century scholars also briefly mention Cedar Grove in works focused on Rockbridge County.

The first known document confirming Cedar Grove’s existence is a Rockbridge County freight record from February 1820. Much of Cedar Grove’s history has been discovered through records from the Rockbridge Historical Society and Washington and Lee University’s Special Collections, Hopkins said.

Catharine Gilliam, in her work “Jordan’s Point — Lexington, Virginia, A Site History,” describes Cedar Grove during its heyday as the “metropolis of Rockbridge.” But once the James River Canal, the primary waterway for shipping goods to Richmond, was expanded to Lexington, Gilliam writes, Cedar Grove was abandoned.

Meanwhile, former Virginia Military Institute Superintendent John W. Knapp also makes brief mention of Cedar Grove as “the head of navigation” in the county in his research article “Trade and Transportation in Rockbridge: The first Hundred Years.” He describes a “flourishing community,” which consisted of a gristmill, a sawmill, a blacksmith, tailor shop and a general store in the 1830s.

Hopkins has worked to fill in the blanks of Cedar Grove’s short existence. Two nearby iron forges likely provided much of the industry for the community: Gibraltar Forge, which was upstream from Cedar Grove by a mile, and Lebanon Forge.

Hopkins has a record from Gibraltar Forge that accounts for 1,120 pounds of bar iron sold in 1841. But historians have found no business records that would identify how many enslaved and free workers staffed the forges, Spurgeon said.

“For businesses [in 19th-century Rockbridge County], the only records you ever find are deeds and some tax records,” Spurgeon said. “But other than that, unless one of the owners just happened to leave account books behind. But businesses were not required to record things publicly besides real estate and taxes. And even then, those records are very minimal.”

In the 1850s and 1860s, roughly 25% of Rockbridge County was enslaved, according to census records cited by Spurgeon. He said it’s fair to assume that Cedar Grove’s population at least consisted of farmers and both free and enslaved forge workers.

A transcript of a 1944 address by Colonel Cole Davis to the Rockbridge Historical Society offers some clues as to how Cedar Grove declined so swiftly. After the Civil War, more valuable iron ore could be found elsewhere, making it unprofitable to continue operating near Cedar Grove, Davis suggests.

In 1856, the 185-acre Cedar Grove Mill was put up for sale and listed in the Richmond Enquirer, a former newspaper. The mill was again sold in 1885, according to newspaper records. The mill was still operational in 1917, Spurgeon’s review of records suggests.

Wiped from the map

What Hopkins and Spurgeon can be certain of is that Cedar Grove was wiped from the map in Rockbridge County.

An 1863 map by the Confederate Engineer Bureau shows Cedar Grove alongside the North (later Maury) River. But by the 20th century, Cedar Grove no longer appeared on maps, Hopkins said.

“Cedar Grove just evaporated. It vanished,” he said. “As much as it was a place for 30 to 40 years, it didn’t last.”

Spurgeon said he and Hopkins found enough information to fill a highway marker, and not much more. But the mystery of Cedar Grove is what makes it worth commemorating, he said.

“It’s almost like a ghost town right? And that is part of the purpose,” Spurgeon said. “My understanding for the marker is even people who live in that area were not aware that there was at one time a pretty important commercial transportation hub in that little tiny community.”

Hopkins suspects that the lumber that once formed buildings in Cedar Grove was repurposed, leaving no foundations behind.

A new highway marker

The Virginia Department of Historic Resources approves only 20 markers each year, and applications are competitive, Hopkins said. He said the statewide significance of Cedar Grove’s iron industry helped his marker get approved.

Rockbridge County currently has 21 highway markers, said Jennifer Loux, director of the state’s highway marker program. The state has erected about 2,600 since the marker program started in 1927.

The markers “help bring forgotten sites, such as Cedar Grove, back into the public memory,” Loux said.

Hopkins estimates that it may take 10 months before the highway marker gets posted. For now, a thin wooden post has been placed alongside Virginia 39, right beside the Hopkins’ house. In the Hopkins’ backyard on a wet January day, the murky-brown Maury River gushes by.