Want more news about Virginia’s changing demographics? We’ve collected all our demographics coverage in one place.

Henry County has a problem that most localities in Virginia have. Henry County just has it to a bigger degree. Whether Henry County can solve that problem will determine what kind of future the county has.

Henry County has too many people dying and too few babies being born.

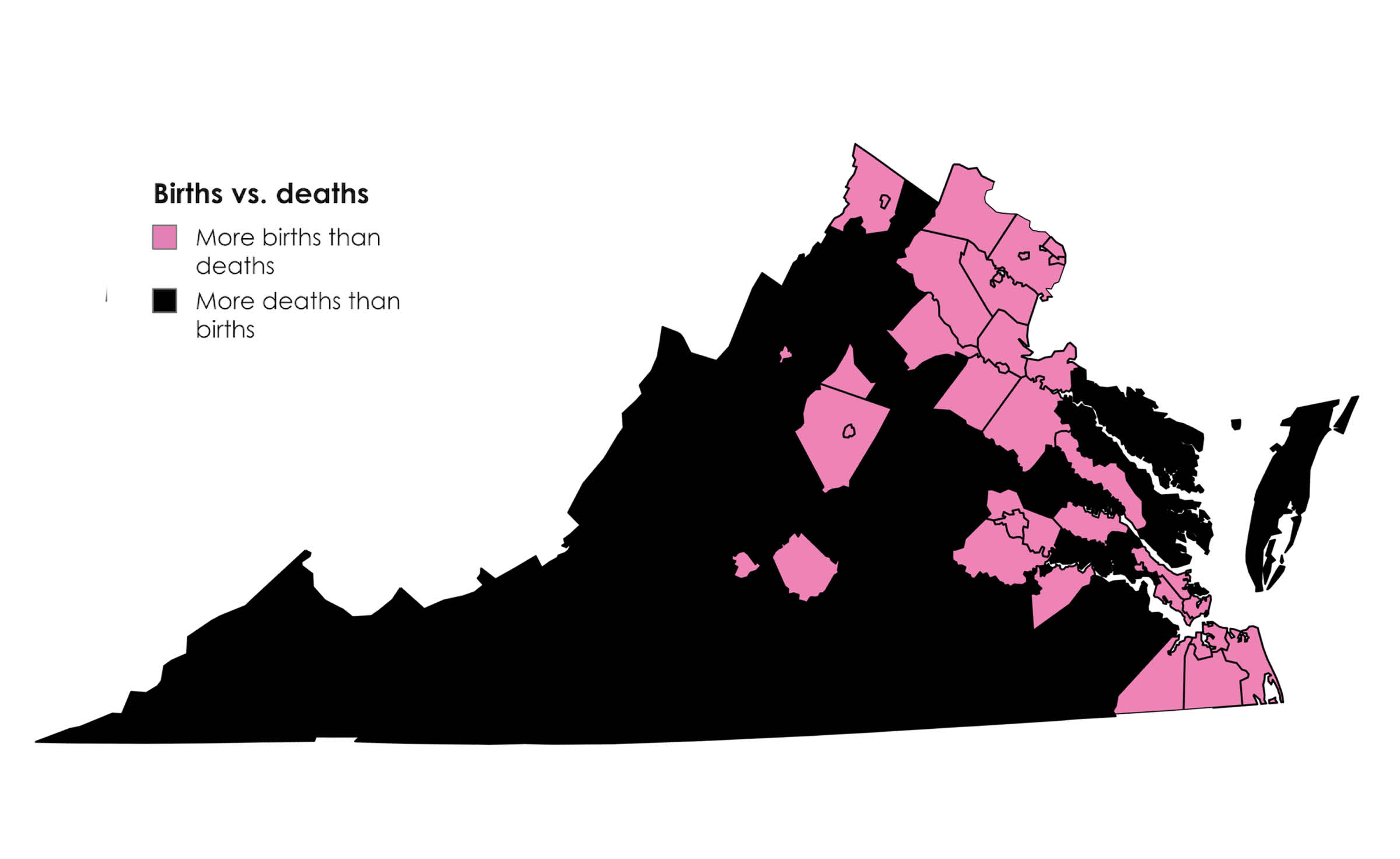

Most localities across Virginia are in the same situation — with an aging population and a declining birth rate, they have more deaths than births.

But no county has as big an imbalance as Henry County does. From 2000 to 2023, Henry County had 1,481 more deaths than births.

This isn’t new. Henry County has led the state in this dubious category for years now. What’s new is a new round of census estimates that underscore just how out of line Henry County is. To be fair, it’s not entirely Henry County, either.

While 94 cities and counties in Virginia have more deaths than births, only six have recorded an imbalance of 1,000 or more since the last census. Three of them are neighbors: Henry County, Pittsylvania County and Danville. (The other three are Roanoke County, Tazewell County and Washington County.)

That cluster of high deaths-over-births localities is no accident. What we’re seeing here is the demographic consequence of economics. This part of Southside saw the pillars of its economy collapse about a quarter-century ago — the sudden and traumatic implosion of the furniture and textile industries. Up until 2000, Henry County had been almost consistently gaining population with each census count. That year, Henry County’s population was numbered at 57,930, its highest ever.

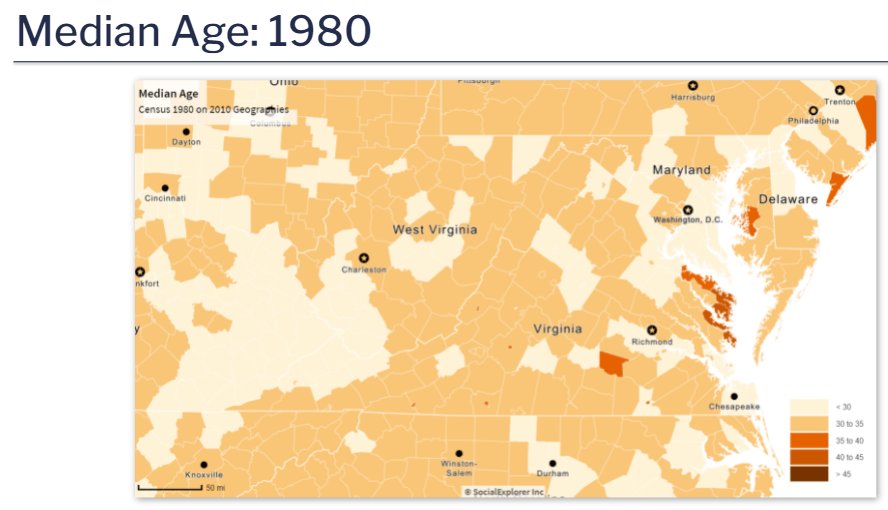

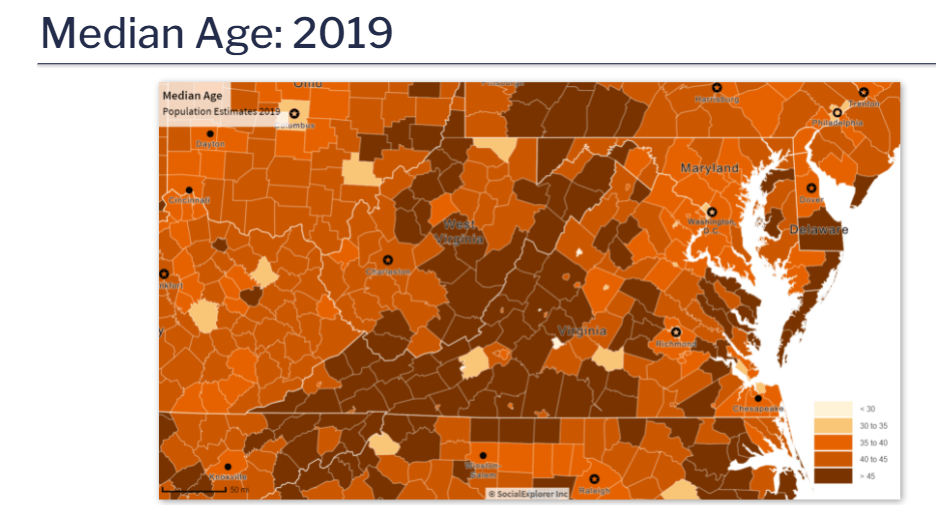

That was also the year that Tultex shut down, idling about 3,000 workers in and around Martinsville and Henry County. Over the next decade, furniture plants shut down. Not surprisingly, many people left the area in search of work elsewhere. That had the effect of both lowering the population and raising the median age of the population that remained. Given the overall aging of our society, the median age in Henry County would have risen anyway, but with the underlying demographic trends, it rose even more sharply.

In 1980, Henry County’s median age was 30.5, making it one of the youngest counties in the state. Now its median age is 48.3, one of the oldest in the state.

The latest population estimates, from the Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service at the University of Virginia, peg Henry County’s population at 48,568, returning the county to where it was more than a half-century ago.

Furthermore, Henry County is one of just 19 “double losers” in the state — localities that lost population two ways, by logging more deaths than births and more people moving out than moving in. You’ll see from the map above that those double losers tend to cluster in three parts of the state: the coal counties of Southwest Virginia, the former textile-and-furniture (and tobacco) counties of Southside and other more agricultural Southside counties farther east. (Roanoke is an outlier; I wrote about the Star City’s demographic challenges in a recent column.)

Henry County has company, but it still stands out for its elevated numbers. If there’s consolation here, it’s this: Henry County’s problem is no longer people moving out, it’s people dying.

The latest estimates show that since 2000, Henry County’s population is down by 2,380 people, or 4.7%. Of that decline, 62.2% is due to more people dying than being born.

That’s not much that anyone can do about the first part of that equation. There’s not much that local officials can do about the second part of that equation, either. Birth rates have been declining nationally since 1957, and with an older population, Henry County isn’t likely to produce all that many more babies even if the birth rate were higher. Given those parameters, the only thing local officials can do is to try to persuade more young adults to live in the county and wait for nature to take its course. Of course, virtually every locality in the state is trying to attract more young adults, so it’s not as if this is unique advice, or an easy task.

The main thing that attracts new residents is jobs, so that speaks to the overarching need of Henry County — like lots of other places — to build a new economy after the old one has quit working. On that score, Henry County seems to be doing pretty well. In October 2023, Henry County saw employment in the county hit 24,111, the highest it’s been since December 2007, almost 16 years ago. The Federal Reserve puts that in a larger context. The number of jobs in Henry County has been declining since 1990, a decade before Tultex. The Federal Reserve data, which goes back to 1990, shows that in those years Henry County’s job count peaked at 30,228 in June 1990. It had fallen to 25,883 even before Tultex. The furniture plant closings of the 2000s dropped the job count lower, until Henry County bottomed out in January 2011 at 19,559. Put another way, Henry County lost about one-third of its jobs between 1990 and 2011. Since then, however, Henry County has generally been seeing its job count increase. Before the pandemic, Henry County’s employment was back up to 22,846. The pandemic dropped that, but now Henry County has gained it all back, and then some. People in Henry County may not feel it because of inflation but, in terms of job counts, the recovery is well underway.

It’s hard to reconcile these job gains with Henry County’s continued net out-migration, but I can guarantee you that without those job gains, Henry County would surely have more net out-migration. Demographically speaking, Henry County simply needs more job growth to attract more people, ideally younger adults. Those high deaths-over-births numbers stand out, but what people in Henry County really ought to be paying attention to is reversing the net out-migration. Over the past three years, 899 more people moved out of Henry County than moved in. That’s high — not as high as Fairfax County, which saw a net out-migration of -33,553 — but higher than that of Henry County’s neighbors. The common assumption is that people likely moved out to find jobs elsewhere, and no doubt some did. However, consider this: A housing study last year found that every day 10,784 people from outside Martinsville and Henry County drive into those localities to work, some driving more than 50 miles. If Henry County wants to reverse those net out-migration trends, maybe what it needs is simply more housing so those workers don’t have to drive as far.

Franklin County to the north saw a net in-migration of 491 people, although Franklin has Smith Mountain Lake as a draw. Patrick County to the east saw a net out-migration of just -47 while Pittsylvania County to the east saw -219 — a smaller number than Henry even though Pittsylvania is bigger.

I mentioned early that Henry County is part of a cluster of counties in that part of Virginia that a) are losing population two ways but b) are mostly losing through a high deaths-over-births ratio. Patrick County, Pittsylvania County and Danville all have the same problem; I’ll address Danville specifically in a future column.

You’ll notice there’s one place near Henry County that I haven’t mentioned yet: Martinsville. Martinsville has obviously suffered the same economic trauma that Henry County has. And Martinsville is also losing population, just at a lower rate (-2% for Martinsville vs. -4.7% for Henry County). What makes Martinsville different from Henry County is that it’s seeing net in-migration. Ditto for Danville. The two cities in this part of Virginia are in the process of rebounding, Danville more dramatically. Virginia’s system of local government, with independent cities and counties, separates all these communities in terms of law, but the economy doesn’t see those distinctions at all. Martinsville ought to be Henry County’s best friend because the better Martinsville does, the better Henry County will do.

While most of the numbers I’ve cited in this column are grim — death tends to be that way — there are hopeful numbers, too. The fastest wage growth in the state over the past three years has come in Martinsville and Henry County, a result of a growing manufacturing sector and a tight labor pool. All those trend lines are pointing in Henry County’s favor (Martinsville’s, too), even if the hearses do continue to outnumber the baby carriages.

The 10 localities with the most deaths over births, 2000-2023

- Henry County 1,481

- Roanoke County 1,255

- Tazewell County 1192

- Danville 1,157

- Pittsylvania County 1,112

- Washington County 1,101

- Smyth County 885

- Wise County 834

- Mecklenburg County 821

- Bedford County 803 (This also is a factor in why Bedford is looking at closing a school, which I addressed in a previous column).

The 10 localities with the most births over deaths, 2000 to 2023

- Fairfax County 22,642

- Prince William County 11,782

- Loudoun County 9,941

- Alexandria 4,880

- Virginia Beach 4,760

- Arlington County 4,746

- Chesterfield County 3,339

- Stafford County 2,729

- Richmond 2,294

- Chesapeake 2,218