Standing in the middle of a busy courtroom, people walking and talking all around him, Tom Jackson uttered a question that only a condemned man can ask.

“Do they sing when I get executed or when Claude does?”

To be clear, Jackson wasn’t expecting any choir of angels waiting to serenade him while he is strapped to an electric chair. He asked while rehearsing a scene in a real-life courtroom drama in which he stars as the leading man convicted in one of the most notorious acts of violence in Southwest Virginia history.

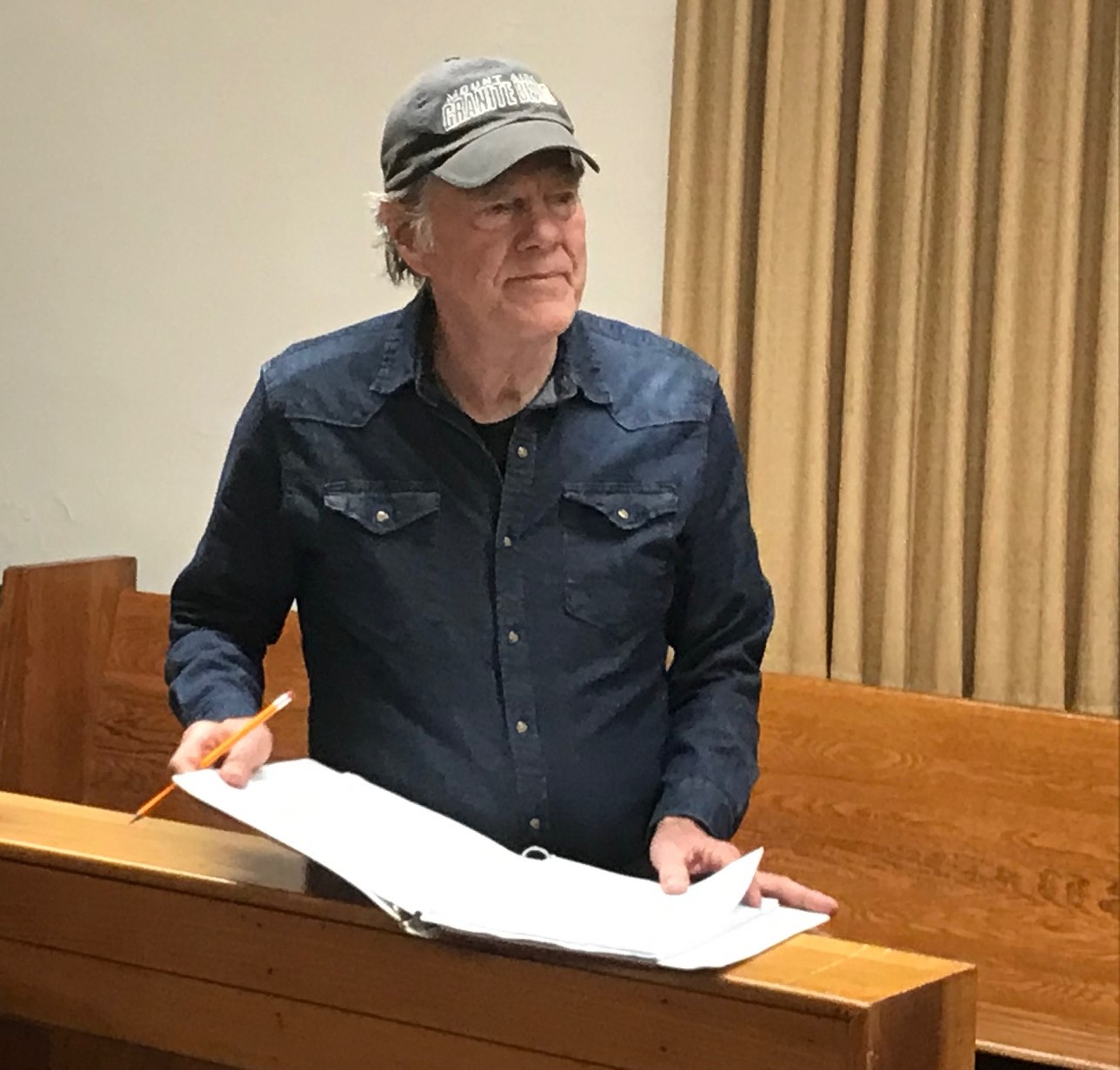

Jackson, a Hillsville lawyer and a former state delegate now turned amateur actor, plays Floyd Allen, one of the principal protagonists in a local play that tells the sad, old story that’s echoed throughout these parts for more than a century: the story of the 1912 shootout inside the Carroll County Courthouse that left five people dead.

“Thunder in the Hills,” a play written more than a decade ago by Carroll County playwright/author/orchardist Frank Levering, is being staged for perhaps the final time in April. Starring a mostly nonprofessional cast of mechanics, attorneys, plumbers, teachers, banjoists, farmers and other local folks, the play was first performed in 2012 as part of the shootout’s 100th anniversary commemoration that included speakers, symposiums, memorial tributes and other events that sought to analyze, deconstruct and publicly reckon with what happened that terrible day.

Performed inside the historic 1873 courthouse where the actual shootout took place, “Thunder in the Hills” became an off-Main Street hit. Tickets for the intended 12-show run sold out quickly in the 120-seat courtroom, prompting two more shows to be added that first year. The same cast and crew gathered for additional performances in 2016, 2018 and 2019 before the pandemic brought down the lights. Heading into April’s 12-show run, the play has been performed more than 50 times to nearly 6,000 people. Proceeds from ticket sales have supported the Carroll County Historical Society’s efforts to save and renovate what locals call the Sidna Allen house in Fancy Gap, another physical link to the tragic events of 1912.

Now, though, the curtain might be closing for good on the play (that is, if the courthouse had a curtain). Most of the local actors are well older than the characters they play, and the demands of rehearsing five nights a week for a month and then performing four weekends are more grueling than they were a decade ago.

Still, the local people who have been involved with this play since the beginning are ready to give “Thunder in the Hills” one more day in court.

“The shadow of this being the last time is falling over the experience,” Levering, the play’s writer and director, said just before a rehearsal in mid-March. “There’s a retrospective mood to some degree. We want to do this reasonably well and put all the pieces together one final time. I think everybody involved in this really loves doing it.”

‘A Greek tragedy’

Some people didn’t think having a play about a terrible tragedy was appropriate.

Generations of Carroll Countians grew up knowing about the shootout, which is often referred around the county as “The Courthouse Massacre” or “The Courthouse Tragedy,” but few knew much beyond the shootout’s broad strokes and familiar names. For decades, a countywide code of silence seemed to grip Carroll County, as blame for the shootout shifted back and forth like the old weather vane that used to rise atop Sidna Allen’s wind-kissed home.

“Carroll County public schools forbade this from being discussed in a school setting,” said Jackson, a longtime attorney who served as a Democrat in Virginia’s House of Delegates from 1988 until 2001. “Emotions ran high 50 years later. People would get red-faced enraged if you wanted to go back and talk about it.”

The story of the courthouse murders is complicated and winds over a more-than-two-year period from late 1910, when a fight between young men set tragic events in motion, until March 1913, when a father and a son died in the electric chair in Richmond. But the story really begins before that and, as already stated, still lives more than a century later.

To summarize: The Hillsville shootout occurred March 14, 1912, when spectators packed the courtroom to hear the verdict in the trial of Floyd Allen, a businessman, alleged bootlegger, occasional lawman and infamous tough guy well-acquainted with using fists and guns to get what he wanted. Allen, who was 55 years old at the time, was on trial for interfering with the arrest of two of his nephews who had been charged in connection with a fight in late 1910. As Carroll County deputies returned with the boys from North Carolina, where they had hidden out, Allen accosted and allegedly beat at least one officer as he freed the boys.

Allen took his kin to jail himself a few days later, but he was charged with obstructing the officers. Months passed before his hearing was held. After a two-day jury trial, Allen was convicted and sentenced to a year in jail. As his lawyer explained to him that they’d appeal the conviction, and as Sheriff Lewis Webb approached to escort him to jail, Allen stood and said, “Gentlemen, I just ain’t a-goin’,” or words to that effect.

A single shot blasted the tension of the courtroom, followed immediately by dozens more fired from all corners. Allen, the defendant, was armed, as were several of his brothers and his son, Claude. People stormed out of the courtroom’s two doors and jumped out of the tall windows. Courthouse employees, who included Clerk of Court Dexter Goad, fired in return as the shootout spilled outside into the street.

When the gun smoke cleared, at least 57 shots had been fired and four people lay dead, and a fifth would die the next day. In the end, Judge Thornton Massie, Commonwealth’s Attorney William Foster, Sheriff Webb, a juror named Augustus Fowler and witness Betty Ayers, who was shot while fleeing and died later, were killed. Most of the “Allen clan” escaped but were eventually captured.

One year after the shootout, Floyd Allen and his 23-year-old son Claude were executed in the same electric chair inside the Virginia State Penitentiary in Richmond. Other Allens and their cohorts were sentenced to prison, but eventually were pardoned by Virginia governors.

Anger simmered for decades as the survivors, the convicted, their descendants, friends and neighbors battled — with words instead of guns — over who caused the shootout. Had the lawless Allens murdered an entire court? Or had they been set up by political adversaries who provoked them into a bloodbath? People staked out territory on both sides as the decades rolled like a never-ending stream down a mountain.

“There are so many pieces to the story,” Jackson said. “It’s one of the most amazing stories I’ve been associated with. It has an overarching theme like a Greek tragedy. Extreme egotism leads to the fall, the tragedy. We’re supposed to learn from that, which is what the Greeks call catharsis.”

The story was ready-made to be turned into a play, but who would dare write it?

Story bears fruit

Frank Levering, now 71, grew up in a farming family in the Wards Gap section of Cana, a community in southern Carroll County wedged hard between the foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains and the state line. The son of Quaker parents who grew apples and other tree fruits, Levering attended Wesleyan University in Connecticut to play football in the early 1970s before later enrolling in Yale Divinity School.

He left divinity school and moved to Los Angeles to become a writer, finding newspaper work and other gigs while he tried his hand at screenwriting. He co-wrote the script for a low-budget, 3-D horror movie called “Parasite,” which came out in 1982 and starred a teenage Demi Moore. (The movie is not to be confused with the 2019 Oscar-winning South Korean movie of the same name.) The movie earned $5.5 million on an $800,000 budget, but garnered bad reviews and Levering struggled to bring another script to the big screen.

When his father fell sick back in Virginia, Levering and his then-wife Wanda Urbanska, herself a writer and journalist, left Los Angeles and moved to the family orchard — where the West Coast city slickers were shocked to discover they were happy and contented with the slower pace of life in the country. The couple’s 1992 book, “Simple Living: One Couple’s Search for a Better Life,” landed them on the bestseller list, earned them a guest spot on Oprah Winfrey’s talk show and placed them at the vanguard of a movement where people found satisfaction in spiritual and simple things, rather than in possessions or career advancement.

Life in the country also gave Levering time and clarity of mind to write. In 1999, he began producing his own plays among the cherry trees in his pick-your-own orchard. This summer, the Cherry Orchard Theatre will begin its 26th season, right after most of the cherries have been picked.

“Thunder in the Hills” has probably become his most popular local production. He had always been intrigued by the shootout story, and the generational mysteries that lingered. In the 1990s, when Levering was president of the local chamber of commerce, Hillsville Mayor Ivan Taylor used to pester him about writing a drama about the courthouse tragedy, which would possibly lure visitors to the area. Levering considered the idea for years, until the approaching centennial of the shootout inspired him to write.

He researched the history, interviewed a few folks, and drew much inspiration from local historian Ron Hall’s book, considered one of the most accurate and balanced accounts of the shootout and the events that preceded and came after it.

“To be honest, I started writing the play out of a sense of responsibility,” Levering said, mentioning how his peace-loving Quaker parents always made public service part of their family tradition.

“This was one thing I thought I could do that could benefit the county.”

Cutting up in the courthouse

During rehearsal on March 14, which was the 112th anniversary of the shootout, the courtroom was filled with laughter instead of the smoke from pistols.

Jackson and Joey Haynes, two attorneys and friends who work in the same office, needled each other in their adversarial roles of Floyd Allen and Dexter Goad, two men who fired bullets at one another outside the courthouse. The wooden steps leading to the courtroom still bear two bullet holes, the final shots Floyd Allen fired toward Goad.

“You’re the man who got me killed,” Jackson called to Haynes. “I’m gonna shoot you the bird!”

“That’s Floyd Allen for you,” Haynes said. “You can’t believe a word he says.”

(Just to be clear, these are not actual lines from the play. Allen didn’t shoot Goad the bird, he shot him with a pistol.)

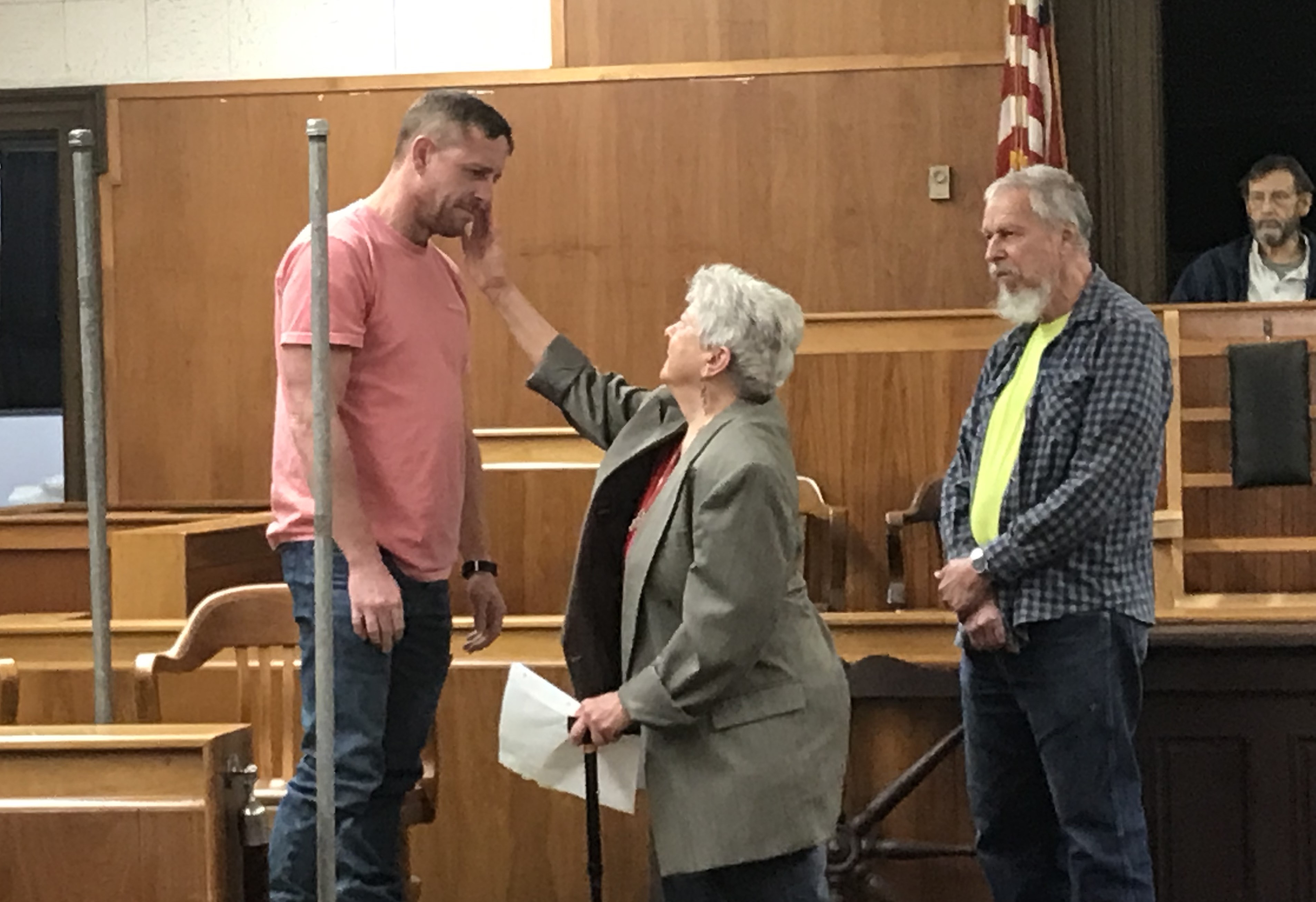

Levity helps cut through some of the tense scenes, which hint at the bloodshed to come. Kay Cox, who plays Sidna Allen’s wife, Bettie, laughed when recounting how a friend vowed to donate money to the historical society if she slapped an unexpecting Haynes in the face during a scene in the play.

“I said, ‘Consider him slapped,’” Cox said. “I slapped the tar out of him.”

She obliged, and the Carroll County Historical Society got its hundred bucks.

Show dates and ticket info

“Thunder in the Hills,” a play about the 1912 Carroll County Courthouse shootout and its aftermath, will be performed 12 times in April inside the historic courthouse at 515 N. Main St., Hillsville.

Tickets are $30 each. A portion of the ticket money goes to the J. Sidna Allen House Restoration project.

Tickets can be purchased in person or by telephone at 276-728-4113 or email at carrollmuseum@yahoo. com. Checks or cash accepted. No credit cards. Checks should be made to Courthouse Productions and mailed to P. O. Box 937, Hillsville, VA 24343.

Shows are:

Friday, April 5 at 7 p.m.

Saturday, April 6 at 2 p.m.

Sunday, April 7 at 2 p.m.

Friday, April 12 at 7 p.m.

Saturday, April 13 at 7 p.m.

Sunday, April 14 at 2 p.m.

Friday, April 19 at 7 p.m.

Saturday, April 20 at 2 p.m.

Sunday, April 21 at 2 p.m.

Friday, April 26 at 7 p.m.

Saturday, April 27 at 7 p.m.

Sunday, April 28 at 2 p.m.

Some performances may already be sold out.

The two-act play runs for about three hours and doesn’t feature a whole lot of light moments, although there are few funny lines to soften the mood. The show recreates the shootout with vintage guns (not loaded with live ammo, fortunately) and follows Floyd and Claude to the gallows.

Jackson is 66 now, having outlived his condemned character by a decade. His portrayals have not endeared him much to Floyd Allen, whom he has begun to see as a prideful, violent man who could have kept the whole powderkeg from exploding had he just swallowed that pride and let the system do its work.

“The older I get, I see him less kindly,” Jackson said. “I think he navigated relationships through intimidation. I anticipate playing him with more of a cutting edge. But in fairness, there was a good side to him that people liked. Thousands of people came to his house in Cana when his body was brought back. Thousands of signatures [on petitions asking for clemency for Floyd and Claude] were sent to the governor. There’s a side to him that people liked. It’s a difficult role to play.”

The role has earned some renown for Jackson that perhaps exceeds the recognition he received as a lawyer and a state legislator. In the 12 years since the play was first staged, Jackson said perhaps 20 people have come up to him and asked if he’s the guy who played Floyd Allen, at places ranging from the Moss Center for the Arts at Virginia Tech to a Pulaski minor-league baseball game to a Tech softball game.

“It shocks me,” Jackson said of the recognition.

Back at rehearsal, Haynes recited a speech his character gives at the grave of one of the victims, prosecutor William Foster. Haynes said that, while delivering the lines, he thinks about his own father who died two decades ago.

“That’s how I do my crying jag,” Haynes explained to his fellow cast members.

“I’m sold,” Levering said. “Nothing like a method actor.”

A county’s catharsis

Back in 2012, as rehearsals started for the play’s initial run, some of the cast members worried that local citizens might consider the play disrespectful, or descendants of the real-life people involved would be angered.

In fact, on opening night in March 2012, some historical society members were so nervous about the possibility of a ruckus, they requested that two sheriff’s deputies be stationed at the courtroom door in case things got ugly.

The deputies were there “for authenticity,” joked Shelby Puckett, a local historian and retired public school teacher who has devoted much of her life to telling Carroll County’s history and the Allen story to the public.

No violence ever occurred, other than the pretend shootout at the end of Act One. Nobody got mad, the families didn’t protest the depictions of their relatives, the citizens didn’t lash out. The play was a smash, which is why they kept bringing it back. The play even spawned shorter spinoffs from Levering’s pen that included “Sidna Allen’s Dream” and “To Catch the Allens,” which was about the Baldwin-Felts detectives’ efforts to hunt the Allens down.

Most of the original cast is still involved. Matthew Utt was 22 when he first played the doomed Claude Allen, the same age as the real man was when the shootout happened. Now, Utt will be 34 when the final run begins, a father who owns a plumbing company and a fellow who also works a third-shift job after rehearsals.

“The county really got behind this play,” Utt said before leaving for work. “It’s been good for the people of this county. You couldn’t have asked for a better cast to do it all these years.”

The play probably helped ease some of the tensions that still hung in the air like Fancy Gap fog for a century. People who had lived all their lives in Carroll County told Puckett, the historian and former teacher, that they never knew much about what happened that day in 1912 because nobody would ever talk about it.

If the story, as Jackson explained it, truly is a tragedy that leads to catharsis, then the play — as well as other centennial events such as visits to the victims’ graves and wreath-layings — allowed the county and its citizens to go through their own catharsis about a tragedy that’s hung over the mountains for generations.

“The wall was torn down,” Jackson said. “The story was told.”

The play gets at something in the hearts of people that a lecture, book or symposium does not, said Puckett.

“In the play, you get the emotions of everything … the anger, the bad feelings that led to it,” said Puckett, who has spent much of the past decade to this play, by answering phones at the historical society, taking ticket orders, attending rehearsals and watching every performance.

“There’s an emotional component that people react to, more than just listening to somebody talk about political differences. We’re not out to commercialize it. We’re telling something really tragic that happened in our county. Maybe there are lessons to be learned from everything that went on.”

And maybe some healing can happen.

Before opening night in 2012, the historical society held a closed dress rehearsal for relatives of the those who were involved, which included families of the Allens and of the Baldwin-Felts detectives who hunted the woods for the Allens. Puckett said that Allen family members watched the rehearsal from one side of the courtroom, the Baldwin-Felts relatives sat on the other side. Nobody spoke a word during the rehearsals.

“The next day they all went out to lunch together,” Puckett said.

The story lives on.