The year 2026 marks the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Cardinal News has embarked on a three-year project to tell the little-known stories of Virginia’s role in the march to independence. This project is supported, in part, by a grant from the Virginia American Revolution 250 Commission. You can sign up to receive a free monthly newsletter with updates. Find all our stories from this project on the Cardinal News 250 page.

As the American Revolution raged into its fifth year of fighting, the Redcoats were the least of Col. William Preston’s problems.

In the summer of 1780, with battles spreading from New England to the Deep South, Preston commanded a militia of Montgomery County men from his sprawling plantation called Smithfield, situated in the green hills of Drapers Meadow, near present-day Blacksburg. In the years since the Declaration of Independence had been signed and Patriots waged war for independence from Great Britain, Preston had learned disturbing facts about many of the men he led: a lot of them didn’t care much for this Revolution business.

How many Loyalists were there?

Historians estimate that 20% to 30% of colonial Americans remained loyal to the British crown. ” Loyalists were most numerous in the South, New York, and Pennsylvania, but they did not constitute a majority in any colony,” according to the Library of Congress. “New York was their stronghold and had more than any other colony. New England had fewer loyalists than any other section.”

About 23,000 New Yorkers signed up with the British army, more than all the other colonies combined, the Library of Congress says. Ultimately about 100,000 Loyalists fled into exile, mostly to modern-day Canada, the library says. That accounted for about 3% to 4% of the colonial population.

Montgomery County was a hotbed of Loyalism, filled with citizens who refused to swear oaths to the Patriotic cause and instead preferred things to remain as they were, with Virginia and the rest of the colonies part of the British empire. People of Southwest Virginia, located hundreds of miles from the seat of power in Williamsburg and even farther from the major battles of the Revolution, were considered part of the “backcountry,” planted along a western frontier where people worried more about Native American ambushes than British invasions.

Hundreds of people across the Southwest Virginia valleys and mountains openly opposed the Revolution and pledged their loyalty to British King George III. The reasons were as varied as the people themselves — some feared reprisals against the rebels should Britain prevail, many feared a British loss would give France more power in North America, while many others simply saw a future under Patriots no better than the current British rule. American colonists who sided with the British were frequently referred to as Loyalists or Tories, and others were called “disaffected,” which meant that they didn’t necessarily support either side in the war, but neither were they positively affected or persuaded by the calls for independence.

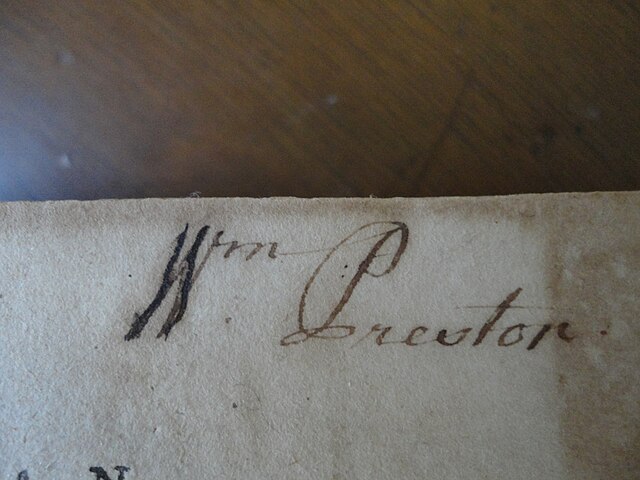

Loyalists caused tremendous headaches for Preston, a former member of the House of Burgesses and one of the largest landowners in western Virginia. Preston’s holdings ran from his Greenfield plantation in Botetourt County west into Montgomery County (which had only been formed a year after the war began when it was carved out of Botetourt County) and deeper into the widening frontier of present-day Kentucky. His status as a businessman and militia leader made him an inviting target for Loyalists, who frequently vowed to attack, scalp or kill him. Many of those who made threats were his very own Montgomery County neighbors and soldiers.

“You live in a rascaly county,” his friend Thomas Lewis of Rockingham County wrote to him. “A majority of Rascals will render any place Rascaly.”

Preston battled home-grown rascals for the entirety of the Revolution.

“The American Revolution was a nasty time in Southwest Virginia,” said Michael Hudson, executive director of Historic Smithfield, where Preston’s 1774 house still stands adjacent to the Virginia Tech campus.

“People look at the Civil War as the time when brother fought brother. If that’s true, then the Revolutionary War is a better example of that idea. The Civil War was generally fought along geographic lines, North versus South. The American Revolution was between neighbors and family members, many of whom suffered severe splits over the war.”

Trouble on the frontier

The Revolution was a wild, fascinating period in Southwest Virginia, even though the region’s stories are vastly overshadowed by history’s focus on the heroic names and adventures of Washington, Hamilton, Franklin and others, and the battles of Concord and Monmouth and Yorktown. The Fort Chiswell lead mines don’t exactly get the same in-depth coverage as Bunker Hill in the history books. Although it saw little direct fighting between Americans and British, Southwest Virginia was filled with acts of murder, terror, hangings, treason and spying throughout the war.

“People think Southwest Virginia had nothing to do with the American Revolution,” said Hudson, Smithfield’s director. “Nothing could be further from the truth.”

In the middle of it all was Preston, who tried to rally people to the Patriotic cause while placating disaffected neighbors. Preston spent much of the war trying mightily to strike a balance between diplomacy and vengeance to keep Loyalism under control in Southwest Virginia.

In 1779, when he learned of a plot by neighboring Loyalists to attack his stately home, where an arsenal of weapons was kept for the local militia, he invited his neighbors to Smithfield where they could talk “in the most neighborly manner,” according to letters written at the time.

Many of the disaffected men promised that they planned no harm to Preston or his large family, but threats persisted for the duration of the war.

“Preston wanted to smooth over disagreements with his neighbors by sitting down and talking things out,” Hudson said.

Preston’s attempts to appease Loyalists even brought allegations against him that he, too, was a British sympathizer. Only when fellow land baron Thomas McGavock, who owned much of present-day Fort Chiswell in Wythe County, vouched for him to Virginia’s ruling House of Burgesses were those allegations dropped.

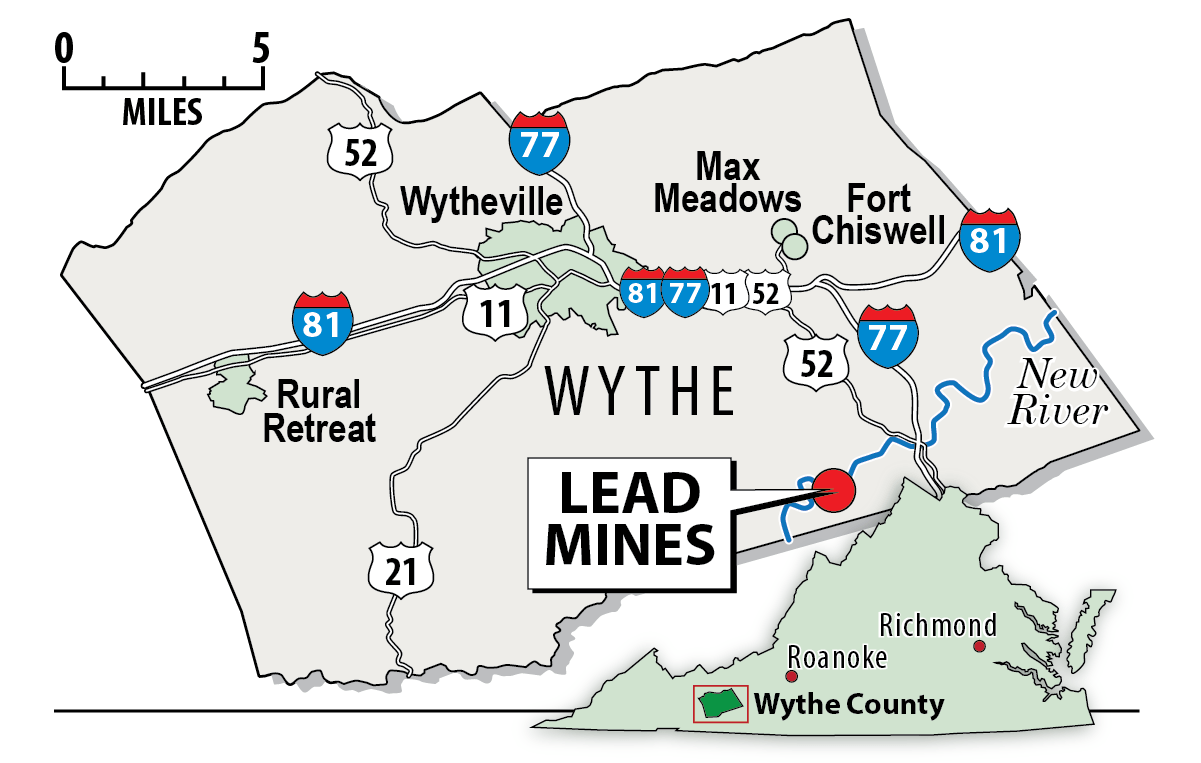

Diplomacy could only do so much, however, especially when armed bands of Loyalists threatened to attack the lead mines in modern-day Wythe County, which supplied materials to make ammunition for the Americans. According to historian Richard Osborn’s 1990 article in the Journal of Backcountry Studies, Loyalists bent on taking over the lead mines openly threatened Preston and McGavock, with main plotter Duncan O’Gullion threatening to scalp both men. Thomas Jefferson, then Virginia’s governor, ordered Preston to protect the lead mines at any cost. The loss of the mines could put the budding country’s future at risk.

Preston often relied on the fighting skills of Col. William Campbell and Col. Charles Lynch, neither of whom possessed Preston’s penchant for talk or appeasement. Campbell pressed his militia from Washington County near present-day Abingdon into Montgomery County, capturing Tories along the way, including a few who were hanged.

Hudson recalls a story during which Campbell even chased a Tory while on an outing with his wife, Betsy. Campbell captured the man near the Holston River, beat a confession out him, then wrapped a halter from the accused man’s own horse around his neck.

Campbell returned to his wife, who asked what had happened.

“Nothing, Betsy,” Hudson said in recounting the story. “We just hanged him.”

Lynch, meanwhile, poured out of Bedford County with 100 men to guard the lead mines near Fort Chiswell. While there, his militia arrested dozens of Loyalists, extracted confessions, freed some, tried others and meted out his own form of punishment, a frontier-style retribution that would eventually become known as “Lynch’s Law,” and later, simply “lynching.”

Lynch himself ominously wrote that, even though he freed some of the plotters who threatened the lead mines, others “may require they should be made Exampels [sic] of.”

(As a side note, during the Revolution, the term “lynching” did not yet have the racial connection with which it would become forever linked in the 19th and 20th centuries, when it most commonly described terrifying, illegal hangings of Black persons. In fact, as Smithfield historian Hudson points out, Col. Lynch “renounced his own slaveholding practices following the conclusion of the Revolutionary War.” That means, in a case of incredible historical irony, that the man for whom the hideous term “lynching” was named was, in fact, a man who freed enslaved African Americans.)

In the article “Trouble in the Backcountry: Disaffection in Southwest Virginia during the American Revolution” that appeared in the book “An Uncivil War: The Southern Backcountry during the American Revolution,” historian Emory G. Evans wrote: “It cannot be proved that Charles Lynch arbitrarily hanged suspected persons without trial, but posterity has attached the phrase ‘lynch law’ to such activity, probably with some reason.”

Loyalists feared ‘a king in every County‘

Loyalism wasn’t just isolated in Montgomery County. Tory sympathies spread along the New River Valley and west toward present-day Bristol and into Kentucky. Botetourt County, where Preston owned thousands of acres, was home to people who swore oaths to the Crown and who were frequently tried in court for disloyalty to the Patriot cause. Pockets of disaffected resistance existed in Southside Virginia. Basically, every rural area west of Virginia’s coastal plain, where the colony’s political and economic power resided, had its share of citizens who didn’t care much for the Revolution. Many county militias struggled to muster enough men because so many citizens were loyal to Britan, Evans wrote.

People stayed loyal to Britain for many reasons. Southwest Virginians have long been a fiercely independent, contrarian people, which is why so many rallied for the Patriot cause during the revolution. But that independent streak revealed itself in a wholly different way among those who defied the Revolution. Evans wrote that “a large percentage of them simply opposed independence on political grounds.” No solitary specific class of people fit the Tory profile. Disaffectedness ran through people of different socio-economic categories and backgrounds. Montgomery County was home to rich landowners, such as Preston, who were patriots, and others, such as Preston’s neighbor Michael Price, with suspected Tory leanings.

The hills and valleys of Western Virginia were also home to many new arrivals in America who traveled to the frontier to find land and their own brand of independence. Some were English, who still felt allegiances to their homeland. Many people had fought side-by-side with the British in the French and Indian War in the 1750s and had no desire to turn their guns toward their former allies a generation later. Many new Southwest Virginians who swore loyalty to England were Germans, who had no specific beefs with King George, but had real fears that a British defeat might allow the French, the Germans’ arch-enemy, to gain power in the West. Many other Southwest Virginians believed genuinely that the Patriots would prove no better rulers than the King had been — and he lived in a palace an ocean away.

Should the Patriots prevail against the British, there “would soon … be a king in every County,” said John McDonald, a Loyalist neighbor of Preston’s.

That insult probably stung Preston, a rich landowner and military leader who was perhaps the most powerful person for hundreds of miles. He was an Irish-born immigrant with Scottish roots whose family emigrated to America in 1738 when he was nine years old and soon found wealth in the quickly growing colony. He grew up in the Shenandoah Valley on land that had been granted by the Crown, and as a young man he excelled in surveying and land speculation.

By the time of the Revolution, Preston had already lived a life filled with adventure, money, power and violence. His work and military service often took him into the Blue Ridge Mountains, which included the future Montgomery County land that would become his home. In July 1755, when tensions with Native Americans were running high along the frontier during the French and Indian War, Preston was nearby when Shawnee warriors attacked Drapers Meadow and killed at least four people. During that attack, the Shawnee party captured a young woman named Mary Draper Ingles and her two sons and took them to their village some 800 miles away. Mary famously escaped her captors and retraced her journey by following the Ohio and New rivers toward home, which she reached in December 1755, becoming a Southwest Virginia legend.

Preston became a representative in Virginia’s House of Burgesses, then, in 1775, joined the committee that drafted the Fincastle Resolutions, a provocative proclamation in response to punitive laws newly enacted by Britain. The signers of the resolutions professed their loyalty to King George, but made plain that they would lay down their lives rather than surrender their “liberty or property to the power of a venal British parliament, or to the will of a corrupt Ministry.” The signers vowed that if Parliament trampled further upon the colonies’ rights “to reduce us to a state of slavery, we declare, that we are deliberately and resolutely determined never to surrender [those rights] to any power upon earth, but at the expense of our lives.”

Not everybody shared their Patriotic zeal.

Tories strike back

Although many Southwest Virginians were flush with Revolution fever, a backlash struck almost immediately after the Fincastle Resolutions were announced. A man named John Spratt “damned” the Fincastle committee and claimed “he could and would raise one Hundred men for the King to enforce the present measures.” He directly threatened the committee with fifteen loads of gunpowder, two of them just for Preston, according to historian Richard Osborn. Spratt never made good on the threats, though.

Preston’s plan to deal with Tories in court subdued some of the immediate unrest, but the numbers of disaffected people and threats grew for the rest of the war. Preston frequently claimed that half of the local population of Montgomery County were anti-Patriot, and he wrote to Jefferson that the region was “the most disaffected part of our State.” Drafting Loyalists into the local militia or punishing them by law were bad ideas because, Preston wrote, “they would either withdraw to the mountains, or … disturb the peace of the county.”

Instead of fighting the Redcoats in great, decisive battles, Preston was relegated mostly to waging the fight of Montgomery County.

“Numbers of people in the county have been so stupid and lost to their own interest as to be disaffected to the present government of the commonwealth ever since it took place,” Preston wrote to Virginia Gen. John Muhlenberg in 1780, his words dripping with palpable contempt and discouragement.

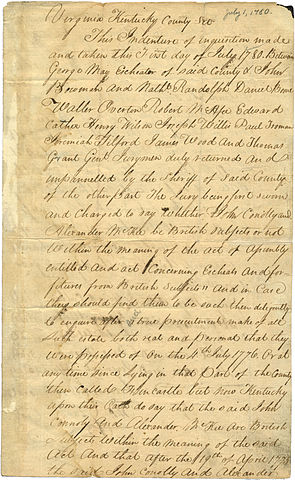

The peak of the Loyalist crisis in Southwest Virginia came in the summer of 1780, when a revolution within the Revolution became a real possibility. That’s when an American spy by the name of John Wyatt infiltrated Tory ranks and discovered their plot to capture the lead mines near present-day Austinville (spies in Wythe County, Tory plots — who said nothing exciting happened in Southwest Virginia during the Revolution?). Wyatt successfully persuaded the Tories to delay their plot and informed Preston about the planned attack, which then gave Lynch and Campbell enough time to march to the lead mines and enact frontier justice against the perpetrators.

Resistance persisted. McGavock, whose property near Fort Chiswell had been attacked a year earlier, resulting in the killing of seven sheep and the threat upon his own life, wrote to Preston that, “We seem but a handful in the Middle, and Surrounded by a Multitude.” A man named John McDonald, the same man who lamented that there might one day be “a king in every county,” told a court that he would pay “no taxes & if they were Inforced [sic] Col. Preston might take care of himself & if any harm followed he might blame himself.”

Preston’s preference for leniency and for talking peacefully to his Tory neighbors about their political differences waned, and he eventually took to calling the Loyalists “stupid Wretches.” Patriots seized and sold property of suspected Tories, and Campbell and Maj. Walter Crockett took justice into their own hands by capturing Tories and executing them, hanging 12 at one time during a raid through Wythe County.

Tories were criminally charged with increasing frequency during the final years of the war. In 1779 and 1780, according to Evans’ research, 168 Montgomery County citizens were charged with breaking anti-Patriot laws, the most of any Southwest Virginia county. People were charged in Bedford, Botetourt, Henry, Pittsylvania and Washington counties. Most of the men charged had been eligible for militia service.

A Patriot’s last stand

Preston’s inability to consistently maintain a fighting militia bedeviled him throughout the war. Following a resounding American victory at King’s Mountain in South Carolina, where bands of Appalachian Mountain men defeated British Loyalists, Preston was asked to take prisoners to the Fincastle courthouse, but he declined by saying the threat of local Tories made such a job untenable.

Preston was also in poor health during the twilight of the Revolution. Even though he was only in his early 50s, the stress of constantly battling local adversaries as well as staving off persistent threats of American Indian attacks had worn on him. Plus, he still ran businesses and farms, including raising hemp to make military products for the Americans, which proved enormously lucrative. He was also heavy and out of shape, which his daughter summed up by saying, “my father is given over to corpulency,” which is perhaps a more genteel 18th-century form of fat-shaming. When he got the chance to join the battle again in North Carolina, his friend John Floyd told the tired, heavy Preston, “I do not think it reasonable that you should stand in the fighting department.” Preston withdrew his militia back to Virginia, just prior to the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, which was fought to a draw but which laid the groundwork for climactic American victories ahead.

“Preston’s efforts to support Virginia’s cause during the rest of the Revolution were an embarrassment to him,” the historian Osborn wrote. He could never sustain a loyal fighting force from Montgomery County, and he was further distraught over the death of his 13-year-old daughter, Ann, possibly from smallpox, after the war ended.

But Preston deserves credit, Osborn wrote, for at least blunting the impact of Loyalist insurrections in Southwest Virginia, for protecting the lead mines and for limiting the fighting with Native Americans. He also saw his businesses succeed during a time of war, and from a family standpoint, except for Ann, his and his wife Susanna’s other 11 children lived to adulthood.

The specter of the Tories hung over him until his death in 1783, just two years after the war’s last major campaign. While inspecting a military muster on the property of his neighbor Michael Price on July 28, 1783, Preston fell ill with a headache and went to lie down. His condition worsened, and family members were summoned, including Susanna, pregnant with their 12th child. He held her hand, having lost the ability to speak, and soon died, possibly from the effects of a stroke.

He was only 53 years old when he died a Patriot, lying in the house of his neighbor Michael Price — a man believed to have been a Tory sympathizer.

Resources for this story included Richard Osborn’s work in the Journal of Backcountry Studies, Emory G. Evans’ “Trouble in the Backcountry: Disaffection in Southwest Virginia during the American Revolution” from the book “An Uncivil War: The Southern Backcountry during the American Revolution,” edited by Ronald Hoffman, Thad W. Tate and Peter J. Albert; interview with Michael Hudson, executive director of Historic Smithfield; and works of the late Patricia Givens Johnson and Jim Glanville.