The year 2026 marks the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Cardinal News has embarked on a three-year project to tell the little-known stories of Virginia’s role in the march to independence. As part of this, I will be writing monthly columns about the politics of the era, written the same way I’d write them today. The events described here took place in 1769.

This project is supported, in part, by a grant from the Virginia American Revolution 250 Commission. You can sign up to receive a free monthly newsletter with updates.

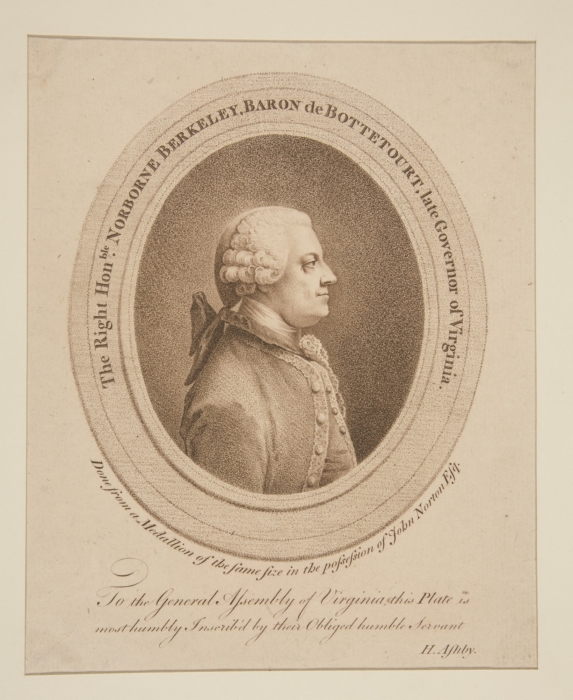

The recent ball held in honor of Governor Botetourt was, by all accounts, a spectacular affair that involved Virginia’s leading ladies and gentlemen parading in their finery.

That congenial evening of drinking and dancing would be unremarkable beyond the society pages were it not for two things:

The host of this soiree was the House of Burgesses — the very same House of Burgesses that the governor had dissolved only months before when it dared challenge London’s authority.

About 100 of the women in attendance wore homemade dresses, which was less a fashion statement and more of a political one — a visible demonstration of the colony-wide boycott in effect against British goods.

So, yes, the Burgesses feted the governor who sent them home, but their wives used the occasion to stage a protest to underscore the very point that the Burgesses had been making that the governor found so objectionable.

If the governor noticed, he didn’t say anything, likely because — the dissolution of the House of Burgesses notwithstanding — he’s an amiable, well-liked fellow who someday will probably have a county named after him.

Perhaps nothing symbolizes the difference between genteel Virginia and the more raucous colonies of the north than our differing responses to the outrages of the latest British attempt to tax the king’s subjects across the sea. In hot-headed Boston, there have been riots and threats of violent confrontations with the British military. Here in Virginia, we respond not with men shouting intemperate words but by women quietly and patiently pushing needles through cloth.

Let’s review how we got here.

After the late war, the one we call the French and Indian War, part of a global conflict known as the Seven Years’ War, Great Britain emerged victorious — and in debt. The king’s government in London took a series of actions to deal with this, all of which have been unpopular in the Colonies. The king forbade settlement west of a certain arbitrary line through our western mountains, which united both land-seekers and land speculators alike. He stationed a standing army in the Colonies, which has mostly served to annoy us rather than protect us. And parliament has set about trying to find even more novel ways to reach into the pockets of American taxpayers.

You’re familiar, of course, with the notorious Stamp Act, by which London attempted to force Americans to pay for tax stamps to affix to all manners of official documents and licenses. After a year of protest — which here in Virginia saw local militia parading through the streets of Tappahannock — parliament finally relented and repealed that odious law. The Colonies apparently made their complaint heard in London — that we on this side of the Atlantic retain the same rights that Englishmen on the other side do, namely that we may only be taxed by our duly-elected representatives. Since we elect no members to the House of Commons, that means our local House of Burgesses is the only body to levee a tax upon Virginians. Not all the British parliamentarians have accepted this concept in principle, but enough seem to have accepted it in practice. Instead of taxing the colonies directly, Parliament now has chosen to tax us indirectly — namely through the so-called Townshend Acts. Named after Chancellor of the Exchequer Charles Townshend, these acts tax our trade. Glass, lead, paint, paper, tea — anything that must be imported, it seems, is now subject to a tax.

This fine print of these laws is even more nefarious. Townshend aimed to use some of the revenue to pay the salaries of Colonial governors and judges. Previously, these officials had been paid by their home state legislatures. Townshend intended to use the power of the purse to sever their allegiance to the colonies they serve and put them in thrall to London paymasters. Townshend passed away not long after the acts were passed, but his laws and their motives have outlived him.

Townshend no doubt thought these laws would bring in a steady stream of revenue. Our gentry are seemingly addicted to imported finery from London; it is how they distinguish themselves from their less fortunate neighbors. Never mind that many of them are now deeply in debt; appearances must be upheld at all cost. Townshend surely did not anticipate that our gentry would do the unthinkable — and stop buying those imported goods because that might signify to all that his financial state had deteroriated. Better to go even deeper in debt than risk such social humiliation. The noted Fairfax County planter George Washington, who distinguished himself in the recent war, is said to have written to friends that any “alteration in the system of my living will create suspicions of a decay in my fortune and such a thought the world must not harbor.”

If Townshend thought he could extract revenue from the vanity of Virginians, he was right — until he was wrong. What he didn’t count on is that the Virginia gentry would band together — and jointly refuse to import British goods. This boycott has produced two salutary effects. First, it’s given the gentry a respectable excuse for no longer buying things they can’t afford. “A scheme of this sort will contribute more effectually than any other I can devise to immerge [sic] the country from the distress it at present labors under,” Washington wrote to fellow Fairfax County planter George Mason because it will give “the extravagant and expensive man” an excuse “to retrench his expenses.” Second, the boycott has delivered a financial blow against a rapacious London government.

Other dispatches

Dispatch from 1766: A sensational murder at Mosby’s Tavern highlights how much Virginia’s gentry is in debt to Britain.

Dispatch from 1766: In Tappahannock, the Stamp Act prompts threats of violence.

Dispatch from 1765: Augusta County mob murders Cherokees, defies royal authority.

Dispatch from 1763: Despite cries of ‘treason!,’ Hanover County jury delivers rebuke to the church – and the crown. (The court case that made Patrick Henry a celebrity.)

Dispatch from 1763: King’s proclamation has united often opposing factions in Virginia (Opposition to the king’s proclamation forbidding western settlement.)

In contrast to the Stamp Act, which fired protests up and down the coast, the Colonial opposition to the Townshend Acts has been slower to develop — but develop it has. Back in 1767, the Philadelphia lawyer John Dickenson circulated a series of essays in which he contended that there was no difference between the direct taxation of the Stamp Act and the indirect taxation of the Townshend Acts — that both were infringements on our English right of self-taxation and thus were unconstitutional. This was a radical interpretation that did not immediately take hold. Instead, more temperate Colonial governments — including ours in Virginia — sent petitions to London merely asking that the acts be repealed. Those requests went unheard, which only set off more vigorous protests.

Boston merchants organized the first boycott, in January 1768, and the enthusiasm for such a protest made its way south, to New York, to Philadelphia, and eventually to Virginia — where the Fairfax planters Washington and Mason have been at the forefront of promoting what’s being called “non-importation.”

Not surprisingly, hot-headed Boston also rioted, which prompted the Colonial secretary in London to order the Massachusetts governor to arrest the rioters as traitors — and send them to Britain for trial. The governor seemed surprised when no one would give evidence against their neighbors. Britain responded by sending more troops to Boston to police the rowdy and uncooperative populace.

By the time the boycott reached Virginia, it’s evolved from a practical response to a philosophical one, which has adopted Dickenson’s once-radical theories about the legality of taxation. That’s why the House of Burgesses chose to meet in secret when it took up Mason’s resolution, which declared “that the sole Right of imposing Taxes on the Inhabitants of this his Majesty’s Colony and Dominion of Virginia, is now, and ever hath been, legally and constitutionally vested in the House of Burgesses.” This resolution had been in the works for weeks, a collaboration with Washington and Richard Henry Lee of the influential Lee family from Westmoreland County.

When Governor Botetourt heard about this resolution, he was apoplectic — a Colonial legislature had just told Parliament it had no power in Virginia. This is the sort of thing that could get a royal governor recalled. He felt he had no choice but to dissolve the House. “I have heard of your Resolves, and augur ill of their Effect: You have made it my Duty to dissolve you; and you are dissolved accordingly.”

What the governor didn’t know is that the Burgesses had already made arrangements to have their resolution printed by Williamsburg printer William Rind, and the resolutions were soon broadcast across Virginia — and the other colonies, as well. The governor also found he had little control over the Burgesses, whether officially convened or not. Once dissolved, the Burgesses simply went to to the nearby Raleigh Tavern and proceeded to work out the details of a non-importation plan.

Even more remarkably, the plan seems to be working — by some accounts, British exports to the Colonies have declined 38%.

Let’s give credit where credit is due: This has only worked because of Virginia’s women: They are the ones who have been spinning the thread and sewing cloth that we now wear — and whose homemade fashions were put on display at the governor’s ball.

The Virginia Gazette wrote about how wonderful it would be “that all assemblies of American ladies would exhibit a like example of public virtue and private economy, so amiably united.”

None of us can tell where this impasse with London is headed, but best it be settled by needles and not by muskets.

Sources consulted include: “Forced Founders: Indians, Debtors, Slaves & The Making of the American Revolution in Virginia” by Woody Holton, Encyclopedia Virginia, Our American Revolution, the Library of Congress, and Colonial Williamsburg.