Sign up for our free weeky email weather newsletter, featuring weather journalist Kevin Myatt.

Never has more hinged on a weather forecast than during the Allied invasion of Normandy 80 years ago Thursday.

So much was riding on so little data. The British and American forecasters charged with determining if there would indeed be a suitable window with less wind and waves to allow such a momentous invasion possessed a minute fraction of the tools and information any amateur weather geek has with a few keystrokes today.

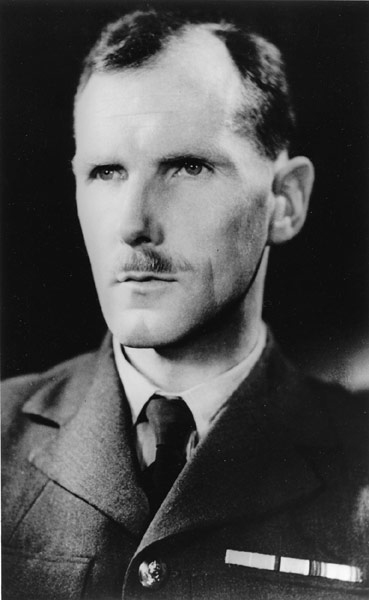

“The team of meteorologists would confer regularly and disagree about the forecast,” the Royal Meteorological Society says on a web page devoted to the narrative of weather forecasting for D-Day. “These meteorologists were operating without technology and equipment that today’s forecasters take for granted, such as satellites, weather radar, computer models and instant communications. Instead, they relied mainly on surface observations from military and civilian weather observers in Britain and in Western Europe and a few military observers at sea.”

See our special report on D-Day

Units from Emporia to Winchester were among the first ones to land in Normandy. Read the “after action” reports from those Virginia units where D-Day survivors described what they did that day.

- Hear Gov. Glenn Youngkin read an excerpt from the headquarters company.

- Hear Bedford County students read an excerpt from A Company from Bedford.

- Hear Sen. Mark Warner read an excerpt from B Company from Lynchburg.

- Hear Sen. Tim Kaine read an excerpt from D company from Roanoke.

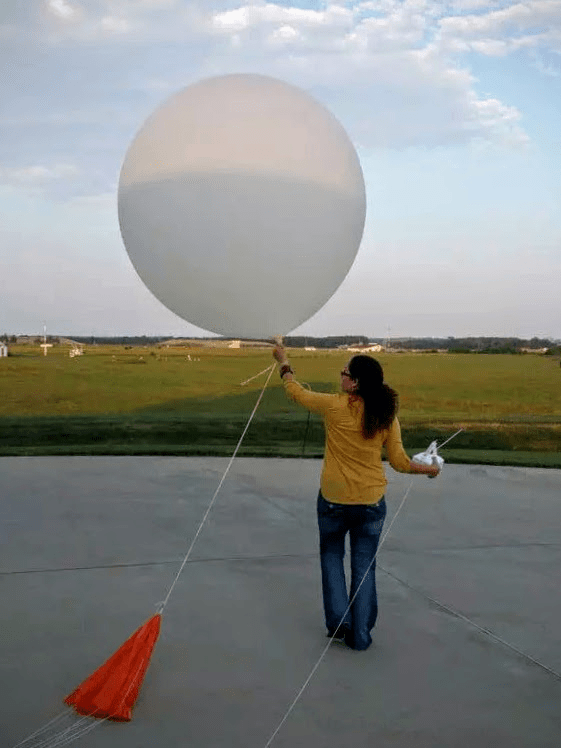

Meteorology in 2024 still suffers from a lack of data even with all of its vast improvements in the past 80 years. It is impossible to gather temperature, humidity, wind and barometric pressure for every cubic millimeter of the atmosphere 15 miles into the sky, so advanced computer modeling has to extrapolate educated guesses of all the missing parameters between surface observations, weather balloon instrumentation, sensors on ships and planes, and radar and satellite data.

What happens in the next few years with artificial intelligence and new information-gathering tools such as phased-array radar may make today’s forecasting seem as quaint by 2044 as the hand-drawn maps of 1944 seem today.

With 80 years’ hindsight and all but a tiny percentage of the survivors of D-Day having passed from their earthly existence, it can seem like almost a historical certainty to those of us born after World War II that the Allies would prevail at D-Day. But from the perspective of the days leading up to the invasion, there was a clear chance the invasion would not be successful, even if the Allies performed their mission expertly and valiantly. Allied Supreme Commander Gen. Dwight Eisenhower prepared a short speech ahead of time should the mission fail, focusing sole blame on himself if the Allied invasion was repelled by the Germans back into the raging seas.

Too much and too little can be made of the importance of meteorology in the Allied victory at D-Day.

The bulk of the credit for the success of the invasion goes to the service personnel who risked and gave their lives on the beaches of Normandy in indescribable horror that June morning and in subsequent days 80 years ago.

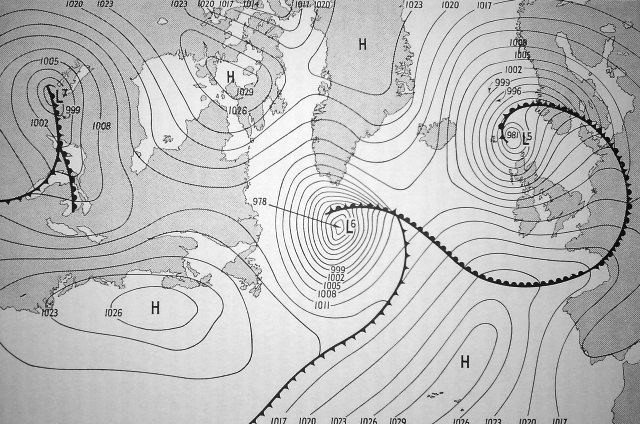

Conditions were still far from perfect for an amphibious landing at D-Day, and some elements of the forecast misfired, such as more clouds than expected over inland France, scrambling some drops of paratroopers. There has even been some analysis that the forecast, while getting the weather generally right for the D-Day landing, was incorrect in its meteorology with the track and evolution of a low-pressure system.

But as any military strategist knows, the slightest edge generated either by skill or fortune can make the difference in victory and defeat. In the case of weather, both skill in forecasting and fortune in conditions in the English Channel turning out as they did both played a role in enabling the invasion to occur a day later than originally planned on June 6, 1944, not having to wait several weeks for another opportunity at low tide with a full moon and striking when the enemy appeared to be doubtful.

In this case, the “observation from a single ship stationed six hundred miles west of Ireland reporting a rise in the barometric pressure” by lead meteorologist James Stagg, the Royal Meteorological Society reports, gave forecasters a clue that a low-pressure system would shift far enough eastward to allow at least somewhat better conditions for an amphibious assault at Normandy. Another account suggests the low-pressure system hung around a little longer than expected, with mixed results for early operations, but it at least delayed the arrival of a second low by a few days as Allied forces began advancing into northern France.

Fortune and skill, multiplied by bravery, were in play at D-Day.

Forecasting today

Weather forecasting in the 21st century is largely done with computers, not hand-drawn maps as they were in the 1940s.

This isn’t a matter of plugging data into a computer and it spitting out a forecast, but rather, information being supplied to several computer forecast models that use slightly different algorithms to come up with a variety of forecast outcomes, which are then analyzed and compared by human weather forecasters, using their own knowledge of atmospheric dynamics, to arrive at a forecast largely hinged on probabilities, not certainties.

Forecasters learn the various biases and common errors of particular forecast models, plus an understanding of the geographical quirks and meteorological history of the region for which they are forecasting.

We’ve retained much of the terminology and symbols that would have been used by forecasters at D-Day, much of which sprang from military planning during prior decades, as air masses were depicted moving along “fronts” much as ranks of soldiers would. Discussions between various meteorologists and forecast offices might still contain disagreements and different viewpoints on available data until a consensus is reached on how to communicate the forecast and any particular weather risks to the public.

But soon, the rise of artificial intelligence may revolutionize weather forecasting like nothing else since World War II.

Individual computer forecast models bantered about on social media and sometimes even displayed by your local television meteorologist are not “artificial intelligence.” Neither is your weather phone app, which often purports to give precise times for when the rain will start, but really doesn’t have any special capability beyond a crude portrayal of the shifting output of a forecast model.

Artificial intelligence, already in testing and limited use, will in the relatively near future enable rapid computations based on thousands of forecast models to calculate probabilities of particular weather outcomes for a given location.

The limitation will be the same as what it was in 1944, though not to the same magnitude, and that is precise data on the state of the atmosphere presently. By considering exponentially more slight variances in the state of the atmosphere and potential resulting weather outcomes, artificial intelligence is expected to have a greater ability to simulate likely weather developments, with human meteorologists still involved to make sure output matches reality and to communicate forecasts and warnings to the public.

The initial data limitation of forecasting was perhaps best described by Ted Ryan, a 20-year science and operations officer at the National Weather Service forecast office in Fort Worth, Texas, who used a portion of the final area forecast discussion he issued earlier this year before taking on a regional operational forecasting role exploring the use of AI, to give a self-described “ted talk” of sorts on the future of forecasting.

“The atmosphere is a nonlinear system, meaning that our ability to forecast it is extremely sensitive to knowing the exact condition of every single breath of air,” Ryan wrote. “We crudely sample the atmosphere directly with instruments that aren’t precise or numerous enough, and make even more approximations with remote sensing like satellites. And while computing power will no longer become the bottleneck in forecast information, the technology and ability to know the initial state of the atmosphere will continue to hold forecast accuracy back.”

Developing the means to collect more extensive and accurate initial data would improve the quality of weather forecasts. One development in radar could particularly assist with more accurate storm warnings.

The future of radar

Radar use for weather detection was taking its first wobbling steps during World War II, more commonly in use to detect enemy aircraft. In 1942, the Navy donated 25 surplus radar units to the U.S. Weather Bureau, the forerunner of the National Weather Service, and important upgrades advanced the radar network in the late 1950s and again in the late 1970s, before the NEXRAD Doppler radar system we know today began being developed in the late 1980s and implemented through the 1990s.

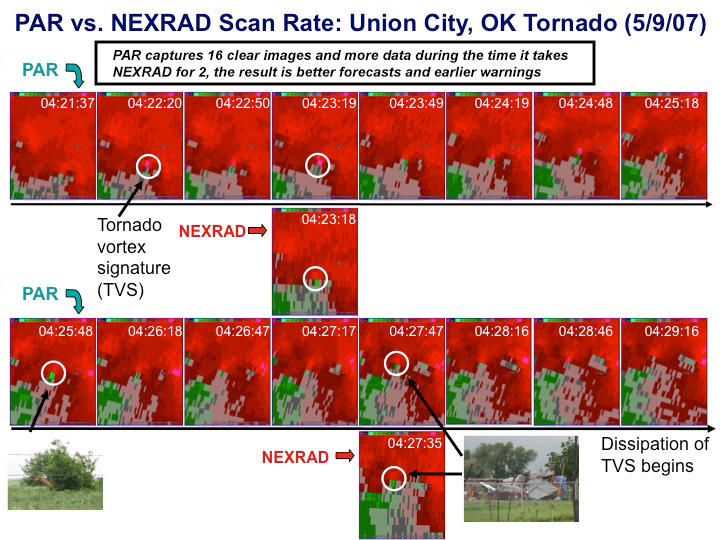

The current National Weather Service radar is called the WSR-88D, or “Weather Surveillance Radar-1988 Doppler.” It revolutionized severe storm warnings with its ability to detect wind motion of particles like raindrops and even lofted debris within storms, enabling forecasters to issue tornado warnings even without physical sightings. But it’s a system that is now nearly 40 years old with an obvious flaw: four to six minutes between scans of a particular storm. A tornado can form, destroy houses, and be gone in that time gap.

“It’s not the same radar as 1988, we’ve improved the components, we’ve done so much to keep it running,” Ken Graham, director of the National Weather Service, said in a visit to the weather service’s Blacksburg office last summer. “It’s not the same radar as it used to be, but it’s still a radar that’s been around a while.”

A technology upgrade that would fundamentally change radar data for storm tracking is called phased array. Rather than a radar dish rotating inside a large dome every four to six minutes, phased-array radar is a panel of antennas that remain in place while sending out radio waves that can be focused electronically wherever the operator wishes. So those radio waves can be focused on thunderstorms, quickly sending back a continuous stream of information, rather than needing four to six minutes for a new scan after turning 360 degrees through what is often mostly clear air back to the target.

Such a development might have helped meteorologists better detect the May 26 tornado at Salem, for instance, as the briefly intense circulation would not have occurred between scans that showed only relatively weak rotation, but could possibly have been detected with a more continuous stream of data.

Implementing such a new radar system will be a matter of political will and fiscal priorities in years ahead, something I dare not broach in this space.

“By around 2028, we’re going to have to make some sort of decision,” Graham said. “Are we going to continue to do upgrades on the components of the current radar, or do we want to replace the network?”

Probabilities, not certainties

Future weather forecasting will be more precise not so much in being deterministic — telling you exactly what time rain will begin and when it will end and how much to the hundredth of an inch will fall at your specific point on the map — but in more precisely detailing probabilities of weather outcomes.

“The role of the meteorologist will become one that communicates the probability outcomes that are important to the people they serve,” Ryan wrote in his discussion. “Some of the kinds of forecasts I think we’ll have in 10 years are the chance: a strong tornado hitting your city in 6 hours, a nearby river flooding your house next week, and a record cold snap or heat wave in 2 weeks, and so on. Monitoring and communicating these kind of probability predictions will help society to be ready for whatever Mother Nature throws at us.”

Preparedness and decision-making are based on probabilities, not certainties. You may choose a route to drive based on the best probability of not being stalled in traffic, with no certainty that something won’t develop as you are en route that will delay you anyway. You may choose a restaurant for an evening meal based on the best probability of not having a long wait, not realizing that a tour bus with 60 people will pull in five minutes before you arrive.

With weather, you weigh the probability of rain in deciding whether to take an umbrella to work or not. On a bigger scale, government and private contractors position various assets depending on the probability of particular weather outcomes, knowing full well those outcomes can vary upward or downward or shift location from the greatest projected probabilities.

This takes us back to D-Day. There were no guarantees meteorologists could give generals about how the weather would turn out, but they provided enough information and expertise to determine there would, in all probability, be a window the operation could move forward early on June 6, 1944. And the rest is history.

Journalist Kevin Myatt has been writing about weather for 20 years. His weekly column, appearing on Wednesdays, is sponsored by Oakey’s, a family-run, locally owned funeral home with locations throughout the Roanoke Valley.