The year 2026 marks the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Cardinal News has embarked on a three-year project to tell the little-known stories of Virginia’s role in the march to independence. As part of this, I will be writing monthly columns about the politics of the era, written the same way I’d write them today. The events described here took place in 1772.

This project is supported, in part, by a grant from the Virginia American Revolution 250 Commission. You can sign up to receive a free monthly newsletter with updates.

The House of Burgesses has cast a landmark vote: It has voted to shut down the transatlantic slave trade.

The king’s government in London has cast a landmark vote of its own: It has blocked the measure.

Make no mistake: This has nothing to do with the liberty or well-being of those poor men, women and children who were captured in Africa, shackled in irons, crammed into slave ships and then transported across the ocean to be bought and sold like livestock.

Instead, it has everything to do with the financial security — and in some cases personal security — of Virginia’s eastern gentry.

London’s rejection of this House measure is now added to a long list of grievances that have been stacking up since the end in 1763 of the conflict that we call the French and Indian War.

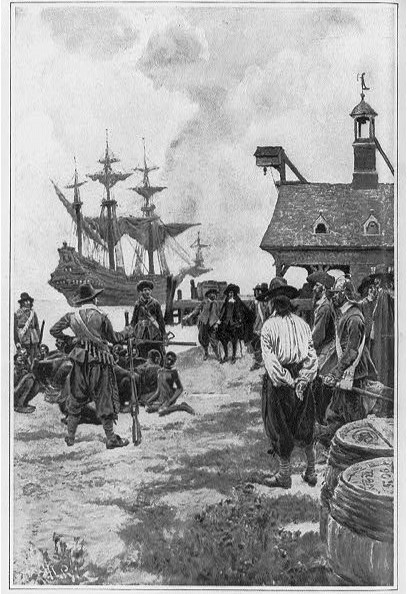

The Spanish had been bringing enslaved Africans to this hemisphere since the 1500s, long before there was a Virginia. However, almost as soon as there was, that practice became rooted here. We all know the story: The White Lion, an English privateer sailing under a Dutch letter of marque giving it the right to plunder Spanish ships at will, intercepted a Portuguese slave ship bound for the colonial Spanish port of Veracruz (modern editor’s note: this is in Mexico) and relieved the captain of his human cargo. The White Lion promptly set sail for Virginia, where the captain sold the “20 and odd” captives for food. Virginia at the time had no laws defining slavery, although that did not stop our forebears from practicing that institution anyway.

Over the years, the flow of enslaved Africans continued, and Virginia enacted a series of laws to govern them. By using a workforce of slaves, plantation owners were able to profit mightily from their free and enforced labor, mostly in the great tobacco fields. However, the presence of slaves has also complicated Virginia society in ways that no one foresaw.

A few Virginians — but for now, only a few — have come to regard enslaving fellow human beings as a moral blot on their character. Up north, Quakers have become known for their opposition to slavery, but when the New Jersey abolitionist John Woolman traveled through the Shenandoah Valley in 1747 he found fellow Quakers not reluctant at all to own their fellow man. He wrote that his congregants told him: “it was the design of Providence they should be slaves.” More recently, some of our leading citizens have begun to express misgivings about the practice, but they also admit they could not maintain their easy way of life otherwise. The radical legislator Patrick Henry is among those to express such conflicted feelings. These soft voices have no impact upon policy.

Let us cut to the chase: What has led some burgesses to want to block the transatlantic trade is fear. In 1700, less than 10% of Virginia’s population was enslaved. By today, it’s about 40%, and that figure is larger in some places. As long ago as 1736, William Byrd II of Charles City County urged Britain to end the importation of slaves or risk a “servile war” between enslaved and free. In some Tidewater counties, the population of the enslaved now exceeds that of the free. Arthur Lee, from the famous Lee family of Stratford Hall in Westmoreland County, has warned: “Would this not be fearful odds should they ever be excited to rebellion?” Indeed, there have been occasional uprisings — small in number, but large in memory.

What has led other burgesses to the same viewpoint is desire — a desire for money. Our enslaved population is increasing mostly through the ways of nature — children are being born into slavery. From a purely economic point of view — which is how many of Virginia’s leading citizens view the matter — we no longer need to import any enslaved labor, we can simply grow our own. More economic matters: As Virginia’s population pushes ever more inland, and even crosses the mighty Blue Ridge Mountains, the market for slaves goes with it. The small farmer in the Piedmont or the valley may not need as many enslaved workers as his more affluent Tidewater counterpart, but he would like some. This is where the law of supply and demand kicks in: For the plantation owner with many slaves at his command, these inland farmers constitute a market to which he might sell his human chattel — but the market price is depressed if the plantation owner must compete with the captain of the newly arrived slave ship. If the transatlantic slave trade were ended, that Tidewater slave master might ease his worries about an imminent slave rebellion — and also fatten his wallet through the sale of some of his laborers.

What we have here is an economic conflict: The Tidewater plantation owners want to end the slave trade to keep the price of slaves high; the Piedmont and western farmers want the slave trade to remain to keep the price of slaves low.

Other dispatches:

Dispatch from 1769: Governor dissolves House of Burgesses; Virginia vows boycott of British goods

Dispatch from 1766: A sensational murder at Mosby’s Tavern highlights how much Virginia’s gentry is in debt to Britain.

Dispatch from 1766: In Tappahannock, the Stamp Act prompts threats of violence.

Dispatch from 1765: Augusta County mob murders Cherokees, defies royal authority.

Dispatch from 1763: Despite cries of ‘treason!,’ Hanover County jury delivers rebuke to the church – and the crown. (The court case that made Patrick Henry a celebrity.)

Dispatch from 1763: King’s proclamation has united often opposing factions in Virginia (Opposition to the king’s proclamation forbidding western settlement.)

This has led to political fights over import duties on these humans in chains. At one point earlier in this century the import duty on a slave was 30% of his or her sale price. During the late war, the Piedmont farmers pressured the House of Burgesses to reduce the import duty to just 10%. Francis Fauquier was governor then and he observed with great clarity that this was a struggle “between the old settlers who have bred [a] great quantity of slaves, and would make a monopoly of them by a duty which they hope would amount to a prohibition; and the rising generation who want slaves and don’t care to pay the monopolists for them at the price they have lately bore which was exceedingly high.”

The gentry, though, typically hold greater sway in the halls of power. Accordingly, the House of Burgesses has voted twice in recent years — in 1767 and 1769 — to double the import duty on slaves and even sent a petition to the Privy Council in London requesting that it ban the slave trade altogether. Both times the Privy Council vetoed the measure — and sent instructions to Virginia’s governors that they should not allow the House of Burgesses to pass such legislation ever again.

The conflict in Virginia is between the large slave owners and the small ones, but it’s also with the slave traders of Britain. The great ports of Bristol and Liverpool do a booming trade in humans. It’s said that between a third and a half of Liverpool’s trade is with Africa and the Caribbean. Many of the city’s leading figures profit from the slave trade. Money talks.

On April 1, 1772, the House of Burgesses again voted — unanimously, it should be noted — to jack up the import duty on slaves to levels that would shut down the pernicious business. The House also sent a special plea to the king: “The Importation of Slaves into the Colonies from the Coast of Africa hath long been considered as a Trade of great Inhumanity, and, under its present Encouragement, we have too much reason to fear will endanger the very Existence of your Majesty’s American Dominions,” the House begged. “We are sensible that some of your Majesty’s Subjects in Great Britain may reap Emoluments from this Sort of Traffick, but when we consider that it greatly retards the Settlement of the Colonies with more useful Inhabitants, and may in Time, have the most destructive Influence, we presume to hope that the Interest of a few will be disregarded when placed in Competition with the Security and Happiness of such Numbers of your Majesty’s dutiful and loyal Subjects.”

The king disregarded the plea and the Board of Trade vetoed the measure. “Such is the influence of a few African merchants,” Arthur Lee said. It seems quite clear the king pays more heed to them than he does anyone on this side of the ocean.

Sources consulted include:

“Forced Founders: Indians, Debtors, Slaves & The Making of the American Revolution in Virginia” by Woody Holton; the Journal of the American Revolution, Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Places, National Museums Liverpool, American Battlefield Trust.