The year 2026 marks the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Cardinal News has embarked on a three-year project to tell the little-known stories of Virginia’s role in the march to independence. This project is supported, in part, by a grant from the Virginia American Revolution 250 Commission. You can sign up to receive a free monthly newsletter with updates. Find all our stories from this project on the Cardinal News 250 page.

In the road to a divorce, sometimes there is a day when a change appears inevitable.

Such a day was June 1, 1774, which the members of the House of Burgesses, in defiance of Lord Dunmore, the royal governor, set aside a Day of Fasting, Humiliation and Prayer.

After meeting at the Williamsburg courthouse, the Burgesses solemnly proceeded down Duke of Gloucester Street to Bruton Parish Church. There, the Rev. Thomas Price implored God to change the minds of King George III and Parliament in order to avert the “calamity” of “civil war.”

June 1 wasn’t the end of Colonial government in Virginia, and the Burgesses still hoped to avoid violent revolution, said Robyn Schroeder, assistant director of the National Institute of American History & Democracy at William and Mary. But, in their determination to achieve “something like sovereignty,” the Day of Fasting, Humiliation and Prayer represented “a doorway that the Burgesses never walk back through.”

The observance 250 years ago was Virginia’s response to events in Massachusetts. On Dec. 16, 1773, Patriots disguised as American Indians threw 342 chests of tea into Boston Harbor to protest a tax on tea.

To punish the Colonists for the Boston Tea Party, Parliament passed — and King George III approved — the Boston Port Act, which closed the port to commerce, effective June 1, 1774, unless the Colonists paid for the ruined tea. The unintended consequence was to help unite the 13 Colonies against the British.

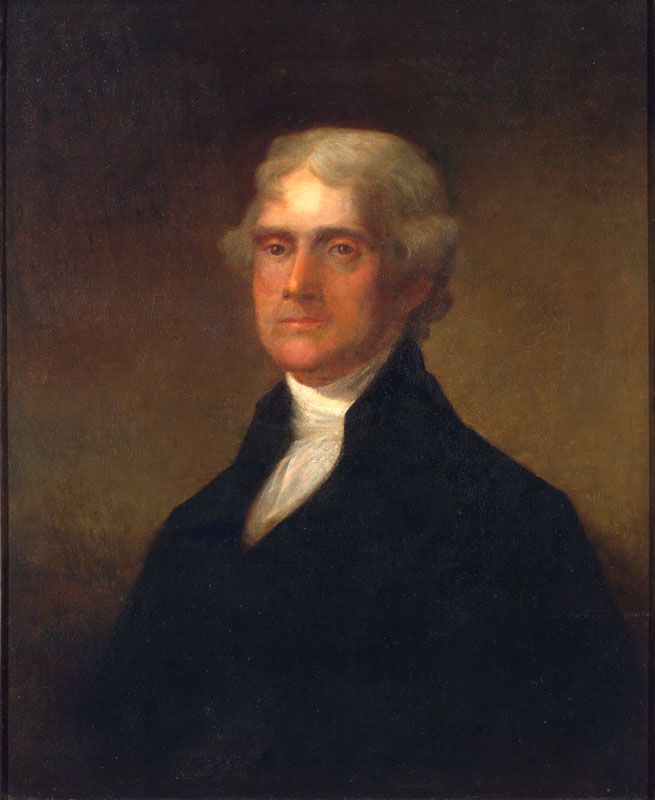

News of this “Intolerable Act” reached Virginia on May 19, 1774. Virginia’s Burgesses, meeting in Williamsburg, considered their response. According to Thomas Jefferson’s autobiography, the ringleaders were younger men: Jefferson, Patrick Henry, Richard Henry Lee and Francis Lightfoot Lee, all in their 20s or early 30s, and three or four others. They resolved to “boldly take an unequivocal stand in line with Massachusetts.”

They met in the Council Chamber of the Capitol to use the library there. Somewhat ominously, in light of later events, they pulled a volume on the English Civil War. A website of Colonial Williamsburg, ouramericanrevolution.org, describes John Rushworth’s “Historical Collections” as a “playbook for bringing down the entire English constitutional establishment — the monarchy, the House of Lords, and the Church of England …”

“With the help therefore of Rushworth,” Jefferson wrote, “whom we rummaged over for the revolutionary precedents and forms of the Puritans of that day … we cooked up a resolution, somewhat modernizing their phrases, for appointing the 1st day of June, on which the Port bill was to commence, for a day of fasting, humiliation and prayer, to implore heaven to avert us from the evils of civil war, to inspire us with firmness in support of our rights, and to turn the hearts of the King and parliament to moderation and justice.”

Cathy Hellier is senior historian at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

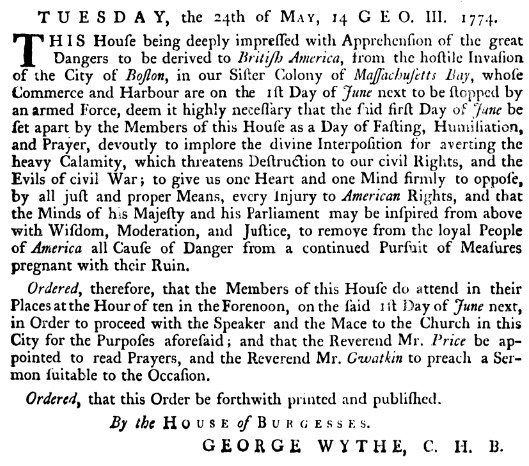

“They thought that a good person to introduce that bill would be a man named Robert Carter Nicholas, who was the treasurer of the colony, who was also known to be a religious man and a moderate,” Hellier said. The resolution was passed unanimously in the House of Burgesses on May 24.

Dunmore saw the printed proclamation on May 26. He viewed it as a “determined resolution to deny and oppose the authority of Parliament,” and believed it might lead to other resolutions that could “inflame the whole Country, and instigate the People to acts that might rouse the indignation of the Mother Country against them.” He summoned the Burgesses to the Council Chamber and dissolved the assembly.

The next day, 89 Burgesses met extralegally at the Raleigh Tavern. “They formed an association calling for essentially a boycott — that term wasn’t used then — of tea and all other goods imported by the East India Company, with the exception of saltpeter and spices,” Hellier said.

They called for a Continental Congress to consider the interests of united America and “declared that an attack on any one colony should be considered as an attack on the whole,” Jefferson wrote.

The Burgesses and others outside Massachusetts became concerned that if the port of Boston could be closed, so could other ports. “They could close off the Chesapeake Bay,” Hellier said.

And yet, it was still business as usual in some respects. The night of the Raleigh Tavern meeting, the Burgesses “gave a ball at the Capitol in honor of the arrival of the Governor’s wife,” Hellier said. “They had planned this, they didn’t cancel it, and all went on as planned.”

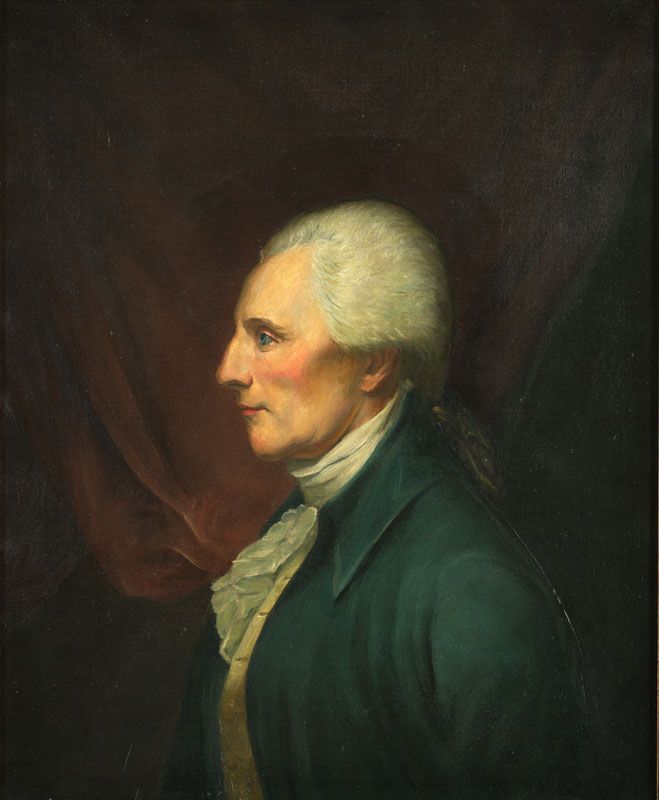

Among those angered by Dunmore’s action was George Washington. In a June letter to George William Fairfax, the future president wrote that “the Ministry may rely on it that Americans will never be tax’d without their own consent [and] that the cause of Boston … now is and ever will be considerd as the cause of America (not that we approve their cond[uc]t in destroyg the Tea) & that we shall not suffer ourselves to be sacrificed by piecemeal though god only knows what is to become of us, threatned as we are with so many hoverg evils as hang over us at present; having a cruel & blood thirsty Enemy upon our Backs, the Indians, between whom & our Frontier Inhabitants many Skirmishes have happend, & with who⟨m⟩ a general war is inevitable whilst those from whom we have a right to Seek protection are endeavouring by every piece of Art & despotism to fix the Shackles of Slavry upon us …”

It’s a rare glimpse of rage from a man famous for emotional control, and he wasn’t the only Burgess angered by the dissolution of the House. “I think it hurts their pride, and what you don’t want to do is hurt Virginians’ pride,” Schroeder said.

The Rev. Thomas Gwatkin, a minister and professor of the College of William and Mary, was appointed by the House to deliver the June 1 sermon.

He wrote it under a “cloud of secrecy,” Schroeder said. “He tells Dunmore to tell Parliament that even though the resolution itself names him as the person who will give the sermon and even though he secretly wrote the sermon for his friend [Rev. Thomas] Price to give, that he doesn’t really want to be associated with it. The ministers at William and Mary who are the schoolmasters are English-born, they almost all leave during the course of the Revolution. They are not Patriots with a capital P.”

At 10 a.m. on Wednesday, June 1, some of the Burgesses — those still in Williamsburg, including Washington — met at the courthouse, along with “every inhabitant of this city, and numbers from the country,” according to the Virginia Gazette. Led by Speaker Peyton Randolph, they proceeded down Duke of Gloucester Street “with the utmost decency and decorum” to the church. There, Price, chaplain of the House of Burgesses, prayed for God’s intervention and delivered a sermon based on Genesis 18:23, Abraham’s question to the Lord about the destruction of Sodom: “Wilt thou also destroy the righteous with the wicked?”

Whether any Black faces were present is not recorded. Enslaved persons sometimes attended Bruton Parish with their enslavers. Ann Wager, who taught African Americans, sometimes brought students. But Schroeder “instinctively” thinks the June 1 service was an “almost entirely white, if not entirely white meeting, because the notion of resistance of authority that is underlying the event being something they don’t want to transmit to slaves.”

Other Burgesses, including Jefferson, had returned to their home counties to organize local observances. “The effect of the day thro’ the whole colony was like a shock of electricity,” Jefferson recalled.

(Still, Dunmore and the House tried one more time to avert a divorce. The royal governor summoned the Burgesses in June 1775 to consider a conciliatory proposal by the Prime Minister, Lord North, but they rejected it.)

A protest march against perceived injustice is a familiar political event. What’s less familiar to modern readers is the religious aspect of June 1. In Colonial Virginia, government and religion were intertwined. George III was by law the head of the Anglican Church.

“Religious people do things for religious reasons,” Schroeder said. Many Colonials are “trying to decouple their sense of God and their sense of the King. We want God on our side, not on the King’s side.”

Some doubted the Burgesses’ religious sincerity. Edmund Randolph “subtly criticized the cynicism of the measure’s authors,” according to ouramericanhistory.org, describing it as “an allowable trick of political warfare.”

In any case, appeals for divine intervention failed to move King and Parliament. Less than a year after the Day of Fasting, Humiliation and Prayer, the Colonies and Crown were in a shooting war.

Many grievances on both sides led up to Lexington and Concord. But if British Colonial authorities had taken more notice of the Day of Fasting, Humiliation and Prayer, according to Edmund Randolph, they might well have interpreted it as the “seed of a revolution.”