A Virginia Tech student is on trial in Belarus, charged with plotting to overthrow the government.

Fortunately for her, she’s not there.

Katsiaryna Shmatsina, a doctoral student at Tech, is one of 20 Belarusian political analysts — all now outside the country — who are being tried in absentia as part of what the Associated Press calls a “yearslong crackdown on dissent in the country” that started first with political activists and now has spread to scholars who comment on politics.

Shmatsina is lucky to be living in Alexandria and not sitting in a prison cell in Minsk: She fled the country on a few hours’ notice and wasn’t completely sure she’d make it until she walked out of the airport in Kyiv, Ukraine, with nothing more than a carry-on bag, an extra pair of shoes and no plan for what to do next.

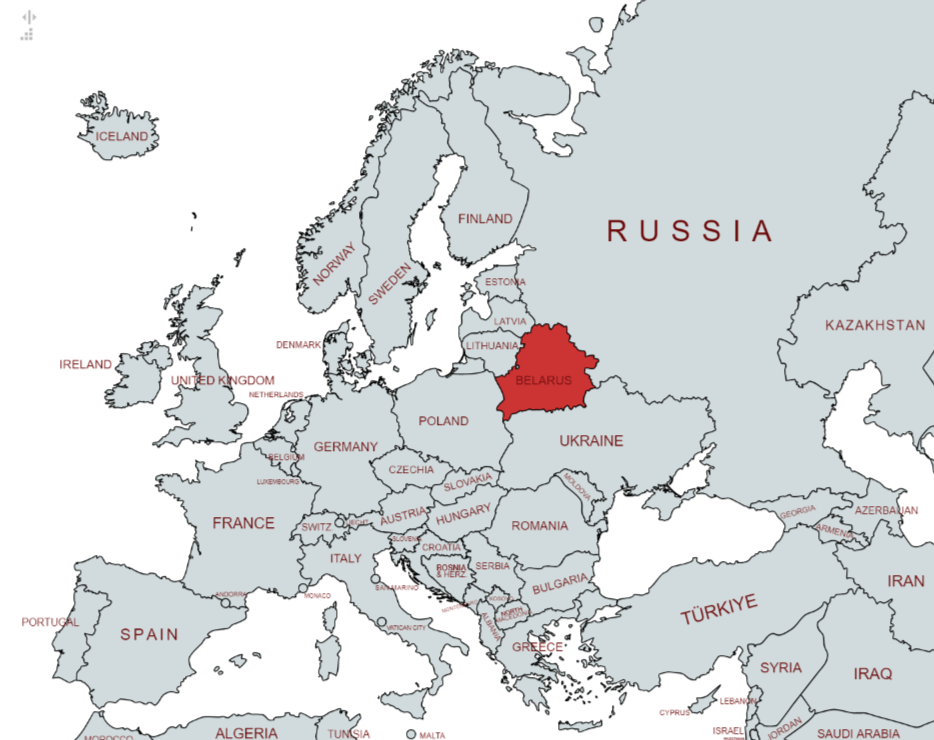

Her story highlights how the methods of the old Soviet regime remain in place in Belarus, a nation of 9.1 million people between Russia and Poland that is essentially a Russian satellite state governed for the past 30 years by Alexander Lukashenko — often called “Europe’s last dictator.”

When I interviewed Shmatsina recently, she was surprisingly good-humored about her situation for someone who literally can’t go home again. “I think it’s pretty good to be wanted by two states,” she said — on trial in her native Belarus and on a wanted list in Russia, as well.

Shmatsina, now 32, grew up in the capital of Minsk and eventually went on to study law at Belarusian State University. Her goal was to be a corporate lawyer. She also says she wasn’t particularly politically minded until she began her law studies and saw how ideological the courses were. “We could see that some courses were eliminated from the curriculum, like human rights. It was a lot of preparing people to be government officials who don’t question the president. You could see this ideology all over the place. At some point, you’re not learning the law, or how to question it. You’re learning just to be part of this authoritarian system. … It’s very much the Soviet legacy. In every group there was someone working with the dean’s office and the dean’s office was working with the KGB,” which remains the acronym for the state intelligence service.

Shmatsina had different ideas. She started volunteering with opposition groups — something guaranteed to attract the eye of authorities. She also insisted on speaking her native Belarusian, a Slavic language similar to, but different from, Russian. “The Belarusian identity is very much repressed by the Lukashenko regime. When I was trying to speak Belarusian in law school, I did not get in trouble but had a few conversations with the dean’s office. They were trying to speak to me about switching to Russian.” Under Lukashenko, the government has made Russian the language of government, and education in the Belarusian language has nearly disappeared.

After law school, Shmatsina went to work for a law firm in Minsk that did a lot of international work. This was at a time when Russia was pushing for more economic integration with Belarus. However, many of the firm’s clients were in the European Union, and Shmatsina could see firsthand how different EU law was from Belarusian law. That proved to be another eye-opening experience.

“Maybe I’m a very sensitive person,” Shmatsina said. She then began her journey into policy work, starting first with the International Republican Committee, a U.S. nonprofit that promotes democracy worldwide. “Idealistic as it sounds, I could not see my country pulled into this Russian sphere of influence,” she said.

That was 2014.

Eventually, she wound up at Syracuse University, where she earned a master’s degree in international relations. While it no doubt enhanced her resume, it also marked her in the eyes of the Belarusian government as tainted with Western influences. She also worked for a time with the American Bar Association on programs dealing with international law. When she returned to Belarus, and continued a lot of her policy work — including volunteering with the World Bank and serving on the board of the Belarusian Organization of Working Women — she began to attract the government’s attention in other ways.

“I knew that the KGB were gathering information and had an interest in my activity for a long time,” she said. “I knew I was on their radar. I was attracting unwanted attention.” She also felt that she and other political analysts were “relatively safe” at the time. “There was no substantial repression against political analysis. The expert community was safe, like the politicians.” Still, there were challenges. “Working independently, not tied to the regime, was a separate adventure,” she wrote in an article for The Lawfare Institute. “It required being cautious. Something as simple as receiving an honorarium for an op-ed was a conundrum: Is it safe to just wire the money to a Belarusian account?” She worried that “listing income from a visiting fellowship in Berlin (which is part of the ‘evil West’) would trigger unwanted attention from the KGB.”

Then came the 2020 elections, where Lukashenko sought a sixth term — although the outcome was never in doubt. His main opponent, Sergei Tikhanovsky, was arrested two days after he announced his candidacy and remains in prison today. Other opposition leaders and political activists were also rounded up.

“Some of my colleagues moved abroad,” Shmatsina said. “I was hoping to stay, planning to stay.”

Then she heard about a Belarusian student who had been studying in the U.S. who returned home to visit his family. “Police broke into his house at 2 a.m. and dragged him out,” she said. “It was a miracle he wasn’t actually held a long time.” She heard of other people being “beaten, tortured, guns pointed at their head.”

For a long time, Shmatsina said she felt she was safe because she wasn’t important enough to be of interest to the government. That began to change. “I was among those people who were visible internationally,” she said. “There were some unpleasant experiences when I knew I was being watched” — such as the mysterious van, likely a police van, that parked outside her house. She also began to realize that while she might now have a high enough profile to interest the government, she wasn’t so prominent that foreign governments would pressure for her release if she were arrested. “I don’t want to be a martyr,” she said. “I’m not ready to go through the [judicial] system.”

About Katsiaryna Shmatsina

Here’s what Michael Cicere, a senior policy advisor at the United States Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe, says about Shmatsina and the situation in Belarus generally:

Katsiaryna is very well known in the Belarusian security and political analysis world, as well as in the context of the human rights and democracy promotion communities that are paying attention to the much deteriorated situation there. Her writing, analysis, and outspokenness on the strategic implications of Russia’s soft annexation of Belarus, the dreadful domestic political crackdown on the population in Belarus, and the role of Belarus in the context of Russia’s imperial war on Ukraine is well known and received in U.S. government circles focused on the region, and the wider community. Our commission interacts to a great extent with various Belarusian dissident and political activist communities, including recently hosting Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, who is widely recognized as the leader of the Belarusian political opposition, and Katsiaryna’s work is well known in that broader context.

The Lukashenka regime, and the Kremlin by extension, has made stamping out Belarusian domestic opposition of any kind a priority in large part because they recognize there are existential implications. Mass protests following fraudulent elections demonstrated that the Belarusian population was not content to be a personal fiefdom of Lukashenka and his kleptocratic, authoritarian system, or a peripheral province of Russia’s revanchist imperial project. As such, crushing all forms of dissent within Belarusian borders and even threatening and in some cases attacking Belarusian dissidents abroad is seen as critical to the regime’s survival, given that it has such little real popular support — instead relying on a local police state backed by Russian forces. Targeting courageous and outspoken dissidents like Katsiaryna should be seen in this context.

Like Ukraine, Vladimir Putin has subordinated Belarus and its people as a kind of sub-ethne that can only exist insofar that it is a branch of a greater Russian identity. These pseudo-ethnic ideations have deep roots that go back to Russian ideological identity formation during the Tsarist period and continued in varying expressions in the Soviet era, as Russian chauvinists sought to appropriate the history and pedigree of Kievan Rus (in present day Ukraine) and suborn Ukrainian and Belarusian peoples/cultures into a manufactured narrative that centers on Moscow. This is both a persistently imperial prism for seeing the region and the world, and explains the Kremlin’s ideological obsession with dominating both Ukraine and Belarus that has persisted for centuries.

As such, while Belarus doesn’t get as much attention, it is an important theater in the struggle for European security. Unlike Ukraine, it has been de facto annexed by Russia and Russian forces who use it as both a staging area for its attacks on Ukraine but also for basing missiles to threaten the rest of Europe, including nuclear arms (in stark violation of its nonproliferation agreements, among other international obligations). People like Katsiaryna are able to clearly and effectively articulate the reality of Belarusian popular dissent against Russia’s takeover there, and represent a reality that the Lukashenka government is illegitimate and a hand puppet for Russian imperium, which is intolerable to both the authorities in Minsk and Moscow.

One day Shmatsina was in a cafe in Minsk when she got word that a policy analyst colleague who was coming from overseas to meet with her had been detained while trying to enter Belarus. Authorities had seized his phone. She knew that she was one of the contacts listed on his phone, and that his calendar would show an upcoming meeting with her.

“Long story short, I had to flee,” Shmatsina said.

She spent the night at someone else’s house. She scrubbed all data from her electronic devices, then intentionally left them behind so they wouldn’t attract attention as she went through customs — if she could get that far. She caught a ride to the airport through a local ride-sharing service similar to our Uber, except that the drivers are presumed to be government informants.

The driver, she said, “didn’t behave like one. He was asking where I was going, how many people I was meeting, why I was leaving the city during a time of protests. It was not a typical chat.”

Shmatsina wasn’t sure she’d be able to leave the country but if she was going to get arrested, she wanted it to be “on my own terms,” she said. “I will show up at the airport rather than someone showing up and getting me in my pajamas.” She bought a plane ticket to Kyiv — that was a place she could fly without needing a visa.

Each step of the process was nerve-wracking. “I wasn’t sure if I could make it past the border control in Minsk airport,” she said. She did. “I was literally still worried when the plane was taking off in Minsk although the boarding was complete.” It wasn’t until she was on the ground in Ukraine — and able to disappear into the city — that she felt safe. “This could sound like overthinking,” she said. “Yet looking back at the Ryanair plane interception in 2021, it doesn’t.” That’s a reference to something that happened a year after she got away. A Belarusian journalist was flying on a Ryanair flight from Greece to Lithuania — over Belarusian airspace — when authorities ordered the plane to land. The journalist, Roman Protasevich, was arrested and later sentenced to prison. He’s since been released but is prohibited from leaving the country.

Shmatsina eventually wound up working for various think tanks in Europe, mostly for the Belarusian Institute for Strategic Studies based in Lithuania. She’s also lectured at a university in Germany and served as a visiting fellow for the European Values Center for Security Policy in the Czech Republic and the German Marshall Fund for the United States.

“Katsiaryna is very well known in the Belarusian security and political analysis world, as well as in the context of the human rights and democracy promotion communities that are paying attention to the much deteriorated situation there,” said Michael Cicere, a senior policy advisor at the U.S. Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe, also known as the U.S. Helsinki Commission, by email. “Her writing, analysis, and outspokenness on the strategic implications of Russia’s soft annexation of Belarus, the dreadful domestic political crackdown on the population in Belarus, and the role of Belarus in the context of Russia’s imperial war on Ukraine is well known and received in U.S. government circles focused on the region, and the wider community.”

Given her growing prominence, Shmatsina thought it logical that she obtain a Ph.D. “I already had experience in D.C. when I did my master’s,” she said. “I thought that was the next logical step. D.C. is a good place for foreign policy.” At one of the many conferences she attended, she met someone from Virginia Tech, and that’s how she wound up a Hokie. She’s currently on sabbatical; her name turns up as author of policy articles in multiple think tank publications (although many aren’t in English, since they’re aimed at a different audience). She’s been interviewed on C-SPAN, EuroNews, The Guardian and the BBC. She also co-hosts a popular podcast, “In the Bunker with Darth Podcast,” and a YouTube channel about Belarus.

Shmatsina, like others in the group of 20 scholars on trial, learned of the charges accidentally — by routine monitoring of Belarusian news sources. “Some of us didn’t even know each other before we heard about the criminal investigation, although the prosecution claims that we, scholars and journalists, were ‘plotting’ as a group to overthrow the regime,” she said. “I was just doing my work as a policy analyst — producing policy papers, conducting research, and using open sources. Doing the typical work a think-tanker would do in D.C., for example.”

Articles by Katsiaryna Shmatsina

Carnegie Endowment: “On the Front Lines: Women’s Mobilization for Democracy in an Era of Backsliding.”

Lawfare: “Watching My Trial for Seditious Conspiracy.”

EU Observer: “In Belarus, the other victims of Putin’s war.”

Podcasts: “In the Bunker with Darth.”

Her reaction when she learned she was on trial back home? “I am relieved to get the news about the trial,” she said. Before, she’d tell people that the government was after her and was afraid that people would think she was being overly dramatic. “There’s a fine line between paranoid and just being cautious,” she said.

To call the proceedings in Minsk a “trial” does an injustice to the word. “None of us have access to the case materials,” she said. “Each of the 20 defendants has pro bono lawyers assigned by the state, but these lawyers avoid contacting us and ignore our emails and calls. Non-pro-government lawyers, who actually dare to represent and defend clients in politically motivated cases, lose their licenses quickly and sometimes end up facing criminal charges themselves. We also couldn’t find a volunteer who could be willing to attend a trial, since it is not uncommon that attendees could get in trouble as well.”

All that is confirmed in a recent article in The Conversation, an Australian-based news site that published an account of the charges and the general political climate in Belarus. The author, Canadian historian David Roger Marples, describes the purpose of the trial this way: “Having silenced critics at home, Lukashenko is now seeking to do so abroad,” he writes, and is specifically targeting younger Belarusian scholars overseas as a way to cut off the next generation of thought leaders from their homeland and make it impossible for them to return. Shmatsina says she couldn’t go home for her grandmother’s funeral, for instance. Even before these charges, “those who return home face arrest if they are known to have protested against or criticized the regime,” Marples writes. “A protest is defined as anything from carrying a placard to liking a critical comment on Facebook.”

Those on trial face up to 12 years in prison if convicted, although since none are in Belarus, that’s a moot point. However, there are potential consequences if these scholars are convicted, Marples writes. “A guilty sentence renders any of the 20 susceptible to arrest by Interpol, the international police organization, in other countries” — so Shmatsina has to be careful where she travels. She’s skeptical they’d actually be wanted by Interpol. Still, “when I was in the EU, I was very cautious about traveling, especially outside the EU.”

Meanwhile, there are other complications: “I’ve been living on short visas here and there,” she said. She’s now applied for political asylum in the United States.

After she learned she was on trial in Belarus, Shmatsina also discovered she’s on a wanted list in Russia. “Not all of 20 researchers in [the] Belarusian criminal case are included on the Russian list — just a few of them,” she said. “So, I don’t quite understand the logic. Could be related to my analyses I wrote on Russian disinformation in Belarus or other commentaries on Kremlin’s ambitions in the region. I am in good company, though: for example, Estonian Prime Minister Kaja Kallas is on the list, too.”

Want more political news and analysis?

I write a free weekly political newsletter that goes out every Friday afternoon —West of the Capital. You can sign up for that or any of our other free newsletters: