The year 2026 marks the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Cardinal News has embarked on a three-year project to tell the little-known stories of Virginia’s role in the march to independence. As part of this, I will be writing monthly columns about the politics of the era, written the same way I’d write them today. The events described here took place in 1774.

If a thief breaks into your home, you’d understandably grab your musket to confront the criminal.

So what recourse do we have when a thief steals our land? Particularly when that thief is none other than the Parliament in London?

Over the course of the past year, Virginia and her sister Colonies have chafed under a series of measures Parliament has passed to crack down on Colonial protests in the wake of tea dumping in Boston Harbor in December 1773. Together, those four acts have come to be known simply as the Intolerable Acts. To their number, we must now add a fifth: “An Act for making more effectual Provision for the Government of the Province of Quebec in North America,” more popularly known as The Quebec Act. Or should I say, unpopularly?

Britain — and, to be honest, most of us American Colonists — have never known what to make of the French-speaking province to our north, although its fate has come to be tied with ours in ways we heretofore could not imagine.

Ostensibly, this act is simply to regularize British government of a Colony of French-speaking Catholics who do not adhere to the Church of England, although it contains many provisions that English-speaking Colonists from New Hampshire to Georgia have found threatening to their own interests — because the Quebec Act makes no provision for an elected assembly, which raises the prospect that London might like to strip us of those rights to elect our own representatives.

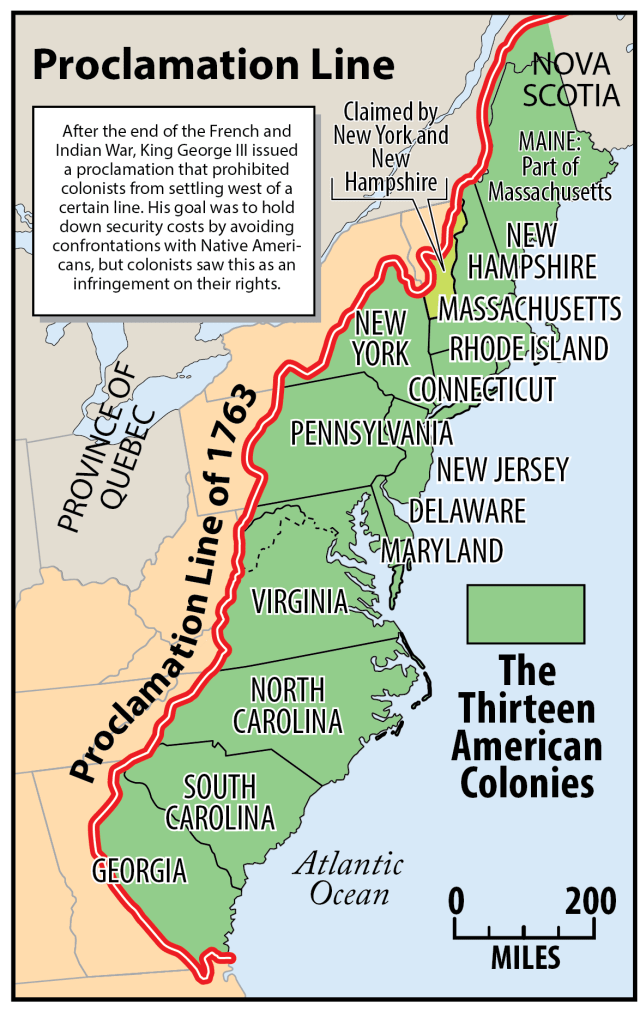

The most directly objectionable part of the act deals with property, not politics: It first strips Virginia of our claims to the land west of the Ohio River. This is a direct assault on the interests of not just Virginia’s gentry — many of whom are avid speculators in western lands — but ordinary Virginians who hold out hope that they might someday settle these lands. Might we remind Parliament that this breaks faith with the veterans of the late war we have come to call the French and Indian War. Of course, this isn’t the first time London has broken faith with those of us on this side of the Atlantic. After that war, the British government paid soldiers with promises of western land — promises that were soon rendered worthless when King George III issued his infamous Proclamation of 1763 that forbids settlement past a certain arbitrary line that runs through the Appalachians (never mind that some of the king’s loyal subjects were already living west of that line).

In the 11 years since that royal edict, Virginians both high and low have been trying to find a way around it. Yes, it’s true that many people have simply ignored the king’s writ and moved west anyway. However, as long as that proclamation remains on the books, no one can enter a settled claim on the land. That’s led many veterans to sell their land, believing they’ll never be able to lawfully possess it anyway. Virginia’s gentry has been quite eager to buy up those rights, gambling that someday they will be able to claim that land and, when they do, make a nice profit from it. Among those who have done so are some of the names we have started to hear more and more out of the House of Burgesses: George Mason and George Washington of Fairfax County, Thomas Jefferson of Albemarle County, Patrick Henry of Hanover County or wherever it is he’s living now. Those gentlemen have now acquired claims to thousands upon thousands of acres of western land that they may never be able to realize. Jefferson, it must be said, has been particularly sly about his investments. A 1754 edict from the Privy Council forbids anyone from taking more than 1,000 acres of native land; Jefferson has invested in two rival land companies as a way to double his holdings.

The king’s rationale for that proclamation was driven by a desire to maintain peace with the native tribes west of the mountains; he didn’t want to pay for another war. Some Colonists grudgingly accepted this — for a time. George Washington assured friends that the proclamation was merely “a temporary expedient to quiet the minds of the Indians.” That “temporary expedient” is now more than a decade old, and the king shows no signs of relenting.

Virginians thirst to push beyond the mountains and settle the land we call Kentucky; this has been forbidden. Governments in Britain believe that relaxing the proclamation to allow the settlement of Kentucky will ignite war with the Cherokees or the Shawnees or the Mingo, all of whom also lay some claim to the land. That hasn’t stopped squatters from moving west anyway.

Because the government has refused to allow legal settlement, illegal settlement has flourished for one simple reason — it’s cheaper. Squatters need not pay any surveyor or any lawyer. This has also made the west lawless, a place where debtors can flee to escape their creditors. We’re told that a judge in Fincastle County (modern editor’s note: This was a county created in 1772 that extended from modern-day Wythe County through southwestern West Virginia into Kentucky; it was abolished in 1776 and divided into other counties) ordered the sheriff to arrest a debtor named Daniel Boone, but the sheriff reported that Boone could not be found because he had “gone to Kentucky.” A writer in the Virginia Gazette has correctly opined that “not even a second Chinese wall, unless guarded by a million of soldiers, could prevent the settlement of the lands on Ohio and its dependencies.” The problem is those settlers have no legal claim to the land they have settled — some might be inclined to pay but won’t do so unless it’s certain they’re paying for a legitimate title. Meanwhile, the gentlemen who own the land grants in the west worry that sometime the British government will simply recognize these “squatter’s rights” and deprive the land speculators of what they have speculated in.

Virginians took hope when Lord Dunmore became governor in 1771. The governor has an expansionist bent and began issuing land to war veterans — well, 10 of them. Not long afterwards, Lord Dartmouth became Colonial secretary in London and instructed Dunmore to stop. (Dartmouth has been a particular disappointment in his role. In New Hampshire, a college has been created in his name in hopes that he might patronize, yet we’re told he opposed its creation and has never given a shilling toward its support). Virginians had hoped that the Proclamation of 1763 might just simply melt away, like the dew. Instead, London has now signaled that it intends to do whatever it can to prevent lawful settlement west of that line — by passing the Quebec Act.

It’s Dartmouth who is said to be the author of one particularly galling part of that legislation — not only does it take the land away from Virginia, the law gives that land to Quebec. It’s not simply that the land is now transferred to another Colony, it’s transferred to one that doesn’t speak English, practices a different religion — and has no elected government. We can see exactly what London is trying to do. Britain hasn’t known what to do with this French colony after it was won in the late war. It was one thing to evict upwards of 11,500 French colonists from the lands in and around Nova Scotia; many of those Acadians, as they called themselves, fled to another French colony, in Louisiana. Quebec, though, is far more populous — 70,000 or so. That’s too many people to deport. Nor can they easily be turned into Englishmen. Britain has tried imposing its own government of occupation that’s not a long-term solution. Now Britain, seeing how restive the English-speaking Colonies are, has decided to appease Quebec by granting the inhabitants their own government — just not an elected one. Britain hopes that Quebec will now be silent while London turns its attention to the south.

As part of that, Britain now extends Quebec into the Ohio Valley and beyond. “Nothing can more effectively tend to discourage” attempts at western settlement than taking that land away from English-speaking Colonies and giving it to Quebec, Lord Dartmouth has said. He intends to use Quebec to block Virginia’s rightful aspirations. And not just Virginia. The royal charters of Virginia, Pennsylvania and New York all guaranteed those Colonies some of the land now transferred to Quebec.

Maybe this is a mere paperwork transfer. However, keep in mind there’s a very active trade route between Montreal and the new city of St. Louis on the other side of the Mississippi River — a French city in the interior, even if it is now technically under Spanish control. Until now, all those French traders crossing the Great Lakes and plying up and down the Ohio River had been traveling through our territories; now they are officially in Quebec. How ironic it is that a British minister would try to drive a French dagger into the heart of Britain’s own Colonies! That’s exactly what the Quebec Act does, though. It’s no wonder that Richard Henry Lee has said that, of all the grievances Virginia is building up against London, that the Quebec Act is “the worst grievance” of them all.

Sources consulted: “Virginia: The Dominion” by Virginius Dabney, “Forced Founders” by Woody Holton, “French St. Louis” by Jay Gitlin, Robert Michael Morrissey and Peter J. Kastor, and Encyclopedia Virginia.

Other dispatches

Dispatch from 1774: More than 30 Virginia counties pass resolutions to protest British response to Boston tea-dumping

Dispatch from 1773: Smuggling in Rhode Island prompts Virginia to do something revolutionary

Dispatch from 1772: Britain vetoes Virginia’s vote to abolish transatlantic slave trade.

Dispatch from 1769: Governor dissolves House of Burgesses; Virginia vows boycott of British goods

Dispatch from 1766: A sensational murder at Mosby’s Tavern highlights how much Virginia’s gentry is in debt to Britain.

Dispatch from 1766: In Tappahannock, the Stamp Act prompts threats of violence.

Dispatch from 1765: Augusta County mob murders Cherokees, defies royal authority.

Dispatch from 1763: Despite cries of ‘treason!,’ Hanover County jury delivers rebuke to the church — and the crown. (The court case that made Patrick Henry a celebrity.)

Dispatch from 1763: King’s proclamation has united often opposing factions in Virginia (Opposition to the king’s proclamation forbidding western settlement.)