As the heart of Virginia’s deer-hunting season looms on the near horizon, Christian Howes has a lot on his mind.

A fanatical bowhunter, the 26-year-old Roanoker is monitoring game cameras he has set up on his hunting spots. He’s doing lots of shooting practice. He’s making sure all of his hunting gear is up to snuff. He’s still knocking on doors, too, hoping to nab permission to hunt a few more places.

But there’s something else on his mind: chronic wasting disease.

While the presence of the fatal deer disease in Virginia’s whitetail herd hasn’t diminished Howes’ passion for hunting, it is something he — and Virginia’s roughly 185,000 other deer hunters — have to keep in mind.

“It can be difficult to understand all the rules,” Howes said recently.

In this case, “rules” aren’t typical hunting regulations like season dates, bag limits and weapons restrictions. Rather, they mostly revolve around what hunters can and can’t do with a deer once the animal is on the ground, for example by establishing mandatory testing zones and carcass transport restrictions.

The rules also include bans on feeding deer, which can concentrate the animals and potentially contribute to disease spread, as well as on the use of hunting lures derived from deer urine.

The rules aren’t intended to eliminate CWD from Virginia’s herd. That would likely be impossible. Instead, the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources’ intent is to try to manage the disease’s spread and impact.

15 years and counting

Chronic wasting disease is an always-fatal neurological disease that affects deer, elk and moose. Related to bovine spongiform encephalopathy (aka mad cow disease) and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, CWD is caused by infectious proteins called prions. Those prions multiply as the disease progresses, eventually causing the affected animal’s brain to, for all intents and purposes, disintegrate into mush.

“Prions are transmitted to uninfected deer directly through saliva, feces, and urine shed by infected deer, and indirectly as a result of soil contaminated with prions,” according to the DWR’s informational website on CWD.

The disease, first confirmed in Virginia in 2009, can remain dormant for months or even years. When animals reach the end stage, they exhibit several key symptoms, including emaciation, drooling and staggering. Animals at that stage are sometimes referred to as “zombie deer.”

CWD is not related to another deer disease that is common in Virginia, and one that has made a visible impact across much of the state in recent weeks. Hemorrhagic disease is a virus spread by biting midges that emerge from mud flats, which become especially prevalent during periods of drought. Many deer that die from HD are found near water because a high fever causes the animals to seek out water sources.

The DWR encourages hunters and citizens to report sick or dead deer. Sightings of deer that exhibit CWD symptoms remain exceedingly rare in Virginia, according to Justin Folks, a wildlife biologist who oversees the DWR’s deer program. It usually takes a very high prevalence rate of CWD to get to that point.

“In Hampshire County, West Virginia, which is ground zero for them, they’ve gotten to that 40% prevalence rate,” Folks said. “They’re seeing those zombie deer falling over dead.”

Folks added that an ongoing GPS collar study in West Virginia will help provide additional information on mortality rates.

Unlike mad cow and Creuztfeld-Jakob diseases, there is no evidence of CWD crossing the barrier between animals and humans. Earlier this year, the 2022 death of two deer hunters from Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease made national headlines, but most experts caution that no definitive link to CWD could be made.

Still, CWD could eventually have a significant impact on Virginia’s deer population.

“In areas where it does hit that 40% prevalence rate, it is the top cause of deer mortality,” Folks said.

But he added that even Western states where CWD has been present for decades still have viable deer and elk populations.

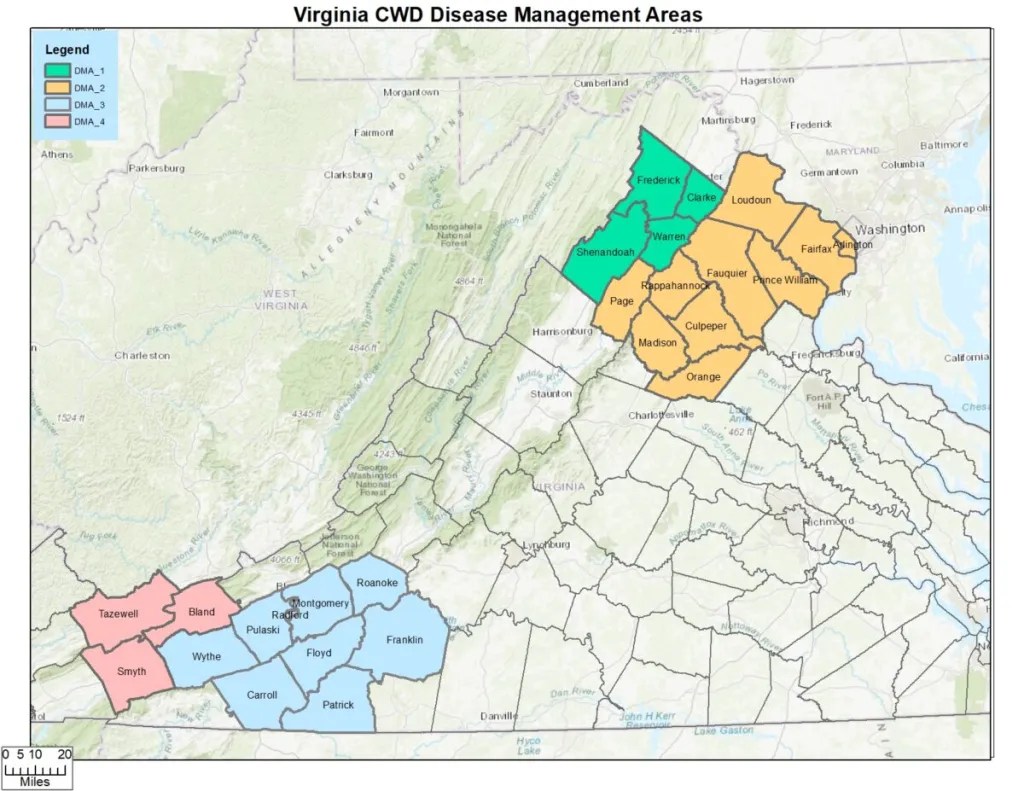

CWD was first detected in Virginia in 2009, in Frederick County, four years after it was found across the border in Hampshire County, West Virginia. It has since been detected in 15 Virginia counties, including Floyd, Montgomery and Pulaski. Of the 71 positives found in the past year — out of nearly 8,000 tested samples — 54 were in northern Shenandoah Valley counties, including a high of 40 in Frederick County.

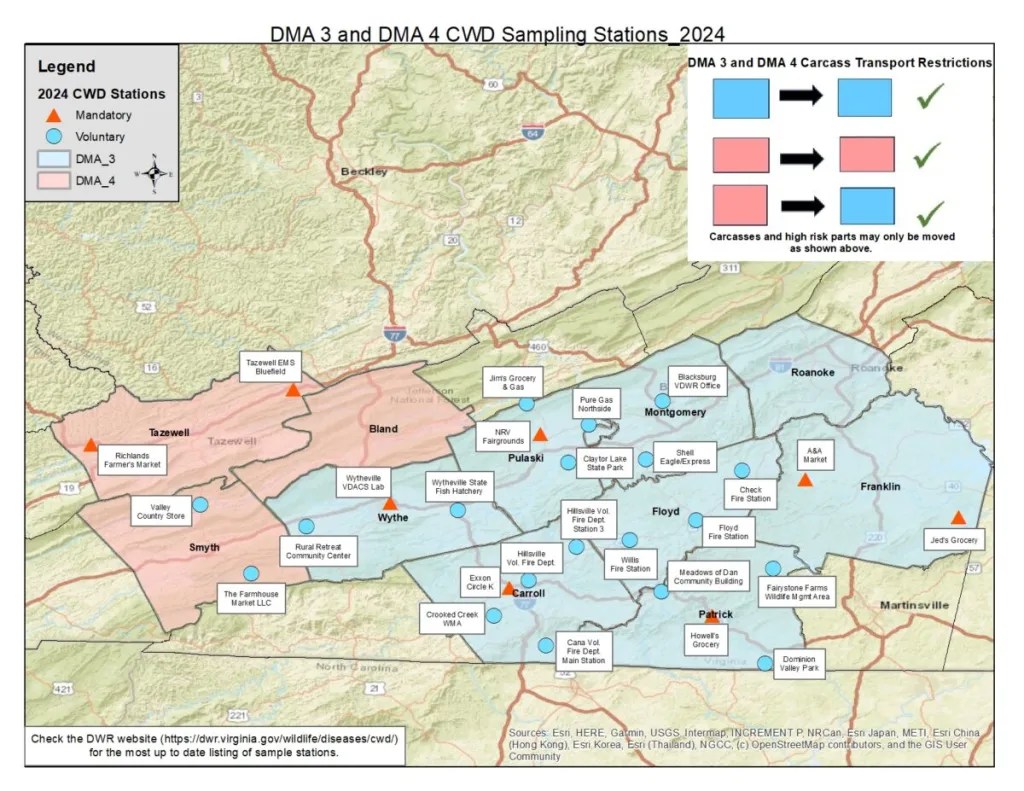

As part of its CWD strategy, the DWR has established four disease management areas. Those include not only counties where a CWD-positive deer has been identified but also counties in close proximity to detections. That’s why Roanoke, Franklin and Patrick counties, even with no positive detections, are included in DMA 3.

Alexandra Lombard oversees the DWR’s chronic wasting disease program. She said the agency’s approach to the disease has evolved.

“In the past, we focused a lot of our efforts on areas where we knew CWD existed,” said Lombard, who is entering her third deer hunting season overseeing the program. “Even before I got here it started to move away from that and … trying to surveil more in areas where we haven’t found it.”

Lombard added that the agency is currently updating its CWD management plan, with a new plan expected in 2026.

“Right now a lot of the regulations we have in place are reactionary, based on disease management areas that are based on positive detections,” Lombard said. “We’re kind of brainstorming and trying to figure out anything we can do that might not be in a regulation, but maybe more outreach and education focused.”

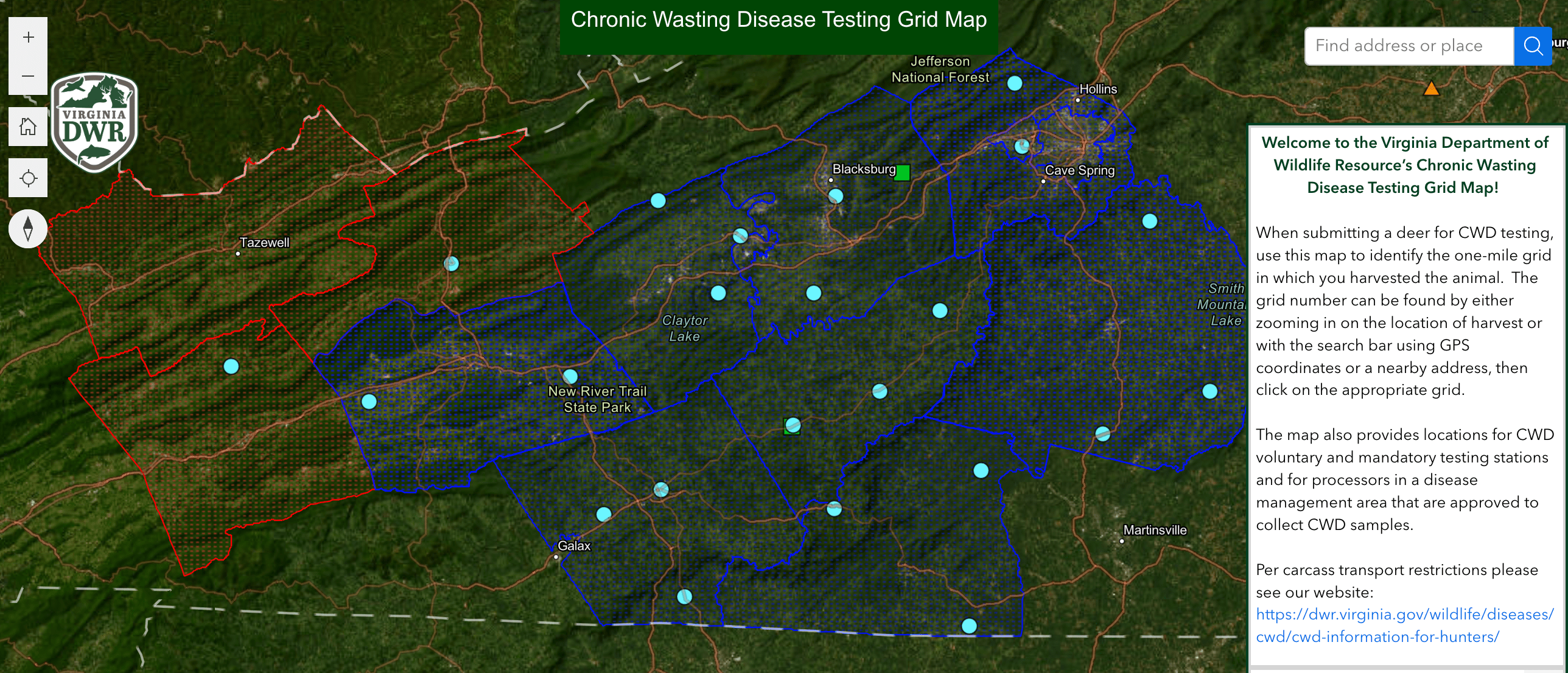

The agency’s website includes extensive information about CWD, including details on carcass transport restrictions and an interactive map showing testing site options, be it for hunters who choose to voluntarily have deer tested or for mandatory testing for hunters who kill deer on certain dates in certain counties.

Among the rules, hunters who kill deer in disease management areas are prohibited from taking a whole deer carcass or parts that include the brain or spinal tissue into a non-DMA county. This can be a challenge for those who hunt in several different counties or who hunt in a DMA county (Roanoke County, for example) but have traditionally taken their deer to a processor in a non-DMA county, such as neighboring Bedford County.

“If a hunter wants to take a deer out of a disease management area, they will need to quarter it or debone it first,” Lombard said. “Our agency, and many deer processors, are trying to increase education on how to do some of these things yourself. Hopefully, we can get more people comfortable with that.”

What can hunters do?

The DWR has compiled an extensive list of cooperating processors and taxidermists who support the agency’s testing program. Last year they played a key role in the collection of nearly 8,000 samples. The interactive map allows hunters to quickly pinpoint the drop-off locations.

Drop-off sites include large refrigerator units set up at places such as fire stations. In fact, as hunting season nears, setting up that drop-off network — including setting up the refrigerators — is a big part of Lombard’s job.

She said hunters need to check state regulations to determine mandatory testing requirements locality by locality.

“For example, Franklin County has mandatory testing on the opening day of rifle season, which is Nov. 16,” Lombard said. “But in Roanoke County, all the testing is voluntary.”

Howes said he plans to have any deer he kills tested, mandatory or not.

“I’m not really worried about it, but why not test the deer?” he said.

Results are typically available in a few weeks.

Hunters for the Hungry, a charitable organization that distributes meat from hunter-killed deer to food banks and similar organizations, requires all deer from CWD-positive counties to be tested.

The DWR offers financial compensation to participating taxidermists and processors to account for the extra work time — which is fortunately minimal — spent collecting tissue samples.

Lombard said hunters, while not necessarily happy about the extra steps, understand the need.

“I talk a lot with processors and hunters,” she said. “Almost everyone I talk to is very receptive to the things I have to say about CWD, and they understand why it is a problem and why these precautions are put into place.”

While the presence of CWD in Virginia is on the minds of hunters, it hasn’t seemed to have a significant impact on hunter behavior. Deer hunter numbers have been steadily declining in Virginia for years, but that’s also the case in many other states — including those with no CWD detections to date — and attributable to a suite of factors, from a changing landscape to Americans’ changing recreational habits.

Virginia hunters are still killing plenty of deer. Last year’s tally of 206,586 was actually a 12% increase from the previous year and proof that not only is the state’s whitetail population still robust but that the state’s hunters remain dedicated to pursuing North America’s most popular big game animal.

Folks said it will remain important for hunters to continue keeping the state’s whitetail herd in check, because CWD, like other diseases, spreads faster in dense deer populations.

Howes, for one, plans to keep doing his part.

“I love deer hunting,” Howes said. “I can’t express it enough. CWD won’t have any impact on that for me.”