The year 2026 marks the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Cardinal News has embarked on a three-year project to tell the little-known stories of Virginia’s role in the march to independence. As part of this, I will be writing monthly columns about the politics of the era, written the same way I’d write them today. The events described here took place in 1774.

Early summer 1774: Two brothers agitate settlers into war with the natives

Virginia is at war.

At a time when most of our political troubles seem to be coming from across the Atlantic, we must now contend with a different kind of trouble from across the Ohio River. Our royal governor, Lord Dunmore, has ordered Virginia’s county militias to mobilize and march west to fight the Shawnee and possibly the Mingo, as well.

How did we get to the point of open warfare? Some might say that Colonists have been in open warfare with the natives of this continent ever since we first arrived, although the immediate details are far more complicated. What until now had been the previous war — some call it the French and Indian War — was fought over the question of who controls the frontier and where that frontier should be. As soon as that war was concluded, with a decisive British victory, did our king open western lands to settlement? No, he issued his infamous Proclamation of 1763 that forbade settlement past an arbitrary line that runs through the mountains. The king pleaded poverty: He did not want to pay for any more frontier wars and has been taxing Colonists ever since, ostensibly to pay for the “security” that British troops do provide.

This proclamation has had multiple effects, all of them bad: Colonists have chafed under these taxes, setting their minds against a distant parliament we did not choose. Both our gentry, who delight in land speculation in the west, and less fortunate Colonists, who crave land, are now united in a mutual desire to secure those western lands — the former for profit, the latter for settlement. The king has also found himself powerless to stop the tide of humanity that has pushed beyond his proclamation line and taken these lands for themselves, even if their legal claim is somewhat dubious. This has, not surprisingly, brought them into conflict with the natives who live there, as well as our fellow Colonists to the north who believe some of these lands belong to Pennsylvania and not Virginia.

Over the years, we have entered into multiple treaties with various tribes — the Treaty of Lancaster in 1744, the Treaty of Logs Town in 1752, the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768 — to define who owned what, but those treaties have been complicated by disputes among the tribes themselves. The Shawnee and the Cherokee do not always agree on whose hunting lands are whose, so it’s quite possible that we have paid for lands that the seller does not legally possess — although the very nature of law is a shadowy notion on the frontier. This should not surprise anyone because even we British Colonists cannot agree on where our own lines are. Take the case of that most desirable confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers to form the mighty Ohio and the outpost known there as Fort Pitt. Both Virginia and Pennsylvania lay claim to this land, and the two Colonial governments have spent much of the spring tussling over who governs there, with no resolution yet.

Events on the frontier have long been out of the hands of the politicians and, it must be said, not everyone on the frontier has conducted themselves in a dignified manner. Near as we can tell, the immediate outbreak of hostilities played out like this: In the spring, two groups of settlers — one led by the Albemarle County surveyor George Rogers Clark, the other by the Maryland speculator Michael Cresap — arranged to meet at the mouth of the Little Kanawha River (modern editor’s note: today this is Parkersburg, West Virginia) and then head on to the land known as Kentucky. Clark’s party arrived first, and while they waited, they heard tales of natives ambushing and killing traders and surveyors floating down the Ohio. When Cresap arrived, the prospective settlers elected him as their military leader, and some wanted to set off to hunt natives then and there. Cresap talked them out of this.

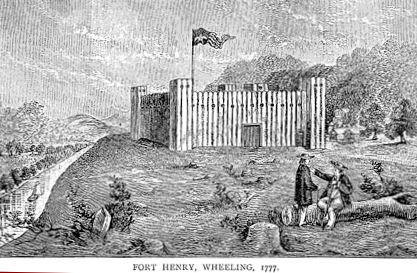

Instead, Clark suggested they go upstream to the settlement of Zanesburg (modern editor’s note: today this is Wheeling, West Virginia) and wait for tensions to calm. However, when they arrived in Zanesburg, they found the place in an uproar about attacks from the natives there. The commander of the Virginia militia at Fort Pitt — (not to be confused with the Pennsylvania authorities who claim the same territory) — sent a message warning that the Shawnee intended to make war, and asked Cresap and Clark to protect the settlers at Zanesburg until more Virginia troops could arrive. Instead, egged on by the brothers Daniel and Jacob Greathouse, some settlers decided to ignore the offer of protection and took matters into their own hands. Whenever they spotted some natives in the river, they chased them downstream and killed them.

Across the Ohio River lives a group of Mingo. The Mingo had been on friendly terms with some of the settlers in Zanesburg, so friendly that the daughter of the Mingo chief had married a prominent local trader. Now, though, those settlers were enraged at all natives, friendly or otherwise. They invited the Mingo across the river for liquor and sport — and killed them. When other Mingo arrived, searching for their missing friends, they were killed, too. By killed, I don’t mean simply shot. The Greathouse brothers were a particularly vicious lot. They seized Koonay, the Mingo woman who was married to a prominent local trader named John Gibson and was pregnant with his child. The vigilantes strung up Koonay by her wrists, sliced open her belly, ripped out her unborn child and impaled it on a stake. This has come to be known as the Yellow Creek Massacre. It’s said that Daniel Greathouse, age 22, is fond of walking around with native scalps dangling from his belt.

As you might imagine, this outraged the Mingo, particularly Koonay’s father — the Mingo chief Logan. He started leading raids on settlers, and soon the Shawnee joined in. Many Virginia leaders reacted to these depredations not with condemnations but with celebrations. “The opportunity we have so long wished for us is now before us,” declared William Preston, a landowner in Botetourt County who previously represented western residents in the House of Burgesses and now serves as surveyor for Fincastle County, whose lands can’t be properly settled as long as there is the threat of warfare with the natives. In other words, these localized hostilities along the Ohio provide the pretext for a wider war to clear the mountain country of natives. (Modern editor’s note: Fincastle County, created in 1772, stretched from Montgomery County to the Mississippi River. It was dissolved in 1776 and divided into three new counties —Montgomery, Washington and Kentucky).

Maybe war on the frontier would have come anyway, but it was the actions of the Greathouse brothers that precipitated the immediate fighting. Some have taken to calling this conflict Lord Dunmore’s War. Perhaps it should really be called the Greathouse Brothers’ War. (Modern editor’s note: Daniel Greathouse died the following year of measles; Jacob was killed later in fighting with the natives).

June 1774: Virginia builds a fort on the Ohio River

In anticipation of hostilities, Governor Dunmore has ordered the construction of a fort near Zanesburg on the Ohio River. William Crawford, a native of Westmoreland County who has lived nearby for the past nine years, making a living as a farmer and fur trader, has been put in charge of the project. It will be named Fort Fincastle, in honor of the governor’s eldest son, the Viscount of Fincastle.

Late summer 1774: Gov. Dunmore mobilizes Virginia militia

Our militia is now on the move. The House of Burgesses seemed to have little interest this spring in the conflict on the distant Ohio River. Instead, it was consumed with the British response to the tea dumping in Boston — the so-called Intolerable Acts. When the Burgesses declared June 1 as “Day of Fasting, Humiliation and Prayer,” Governor Dunmore dissolved the House. The Burgesses since then have taken to meeting informally in Raleigh Tavern and continue to protest the British response. Dunmore, meanwhile, has mobilized the Virginia militia for a western war.

They are dealing with two entirely different problems. We now await word from the west.

August 1774: Virginia militia crosses Ohio River in first battle of the war; results inconclusive

We’ve just received word of the first but no doubt not the last fighting of this frontier campaign. On July 26, a Virginia force under the command of the Falmouth trader Angus McDonald crossed the Ohio River in command of 400 men, with Michael Cresap, George Rogers Clark and Daniel Morgan as his company commanders. They set fire to six native villages and returned with three prisoners and three scalps. It seems unlikely that this will solve anything. On the contrary, this suggests that Virginia will have to send even more troops if it truly hopes to defeat the Shawnee and the Mingo.

It does, however, allow us to call attention to a curious facet of Virginia life — the fate of our western lands is now in the hands of a traitor. Or is it a former traitor? McDonald was a lieutenant in the army of the royal pretender Charles Stuart (aka “Bonnie Prince Charlie”) and fought in the great battle of Culloden where the hopes of the Stuart family’s claim to the throne were finally extinguished. McDonald was “attainted of treason” for backing the pretender’s rebellion and fled to Virginia. He was just 18. He worked several years for a trader in Falmouth, then somehow made his way into Virginia’s military service. He fought in the French and Indian War and later served as a post-war leader of the Frederick County militia. McDonald has served as an attorney and land agent for Lord Fairfax on the Northern Neck, but multiple governors have turned to him for his military acumen — mostly recently his fellow Scotsman, Lord Dunmore. The new world has offered McDonald redemption for his crimes in the old. (Modern editor’s note: In 1776, McDonald was appointed sheriff in Frederick County and commanded the militia both there and in Augusta County. As the revolution got underway, George Washington made him a lieutenant colonel of Virginia forces, although that appointment didn’t last long. McDonald died in 1778 after receiving an incorrect dosage of medicine.)

Fall 1774: Governor will personally lead troops into battle along the Ohio River

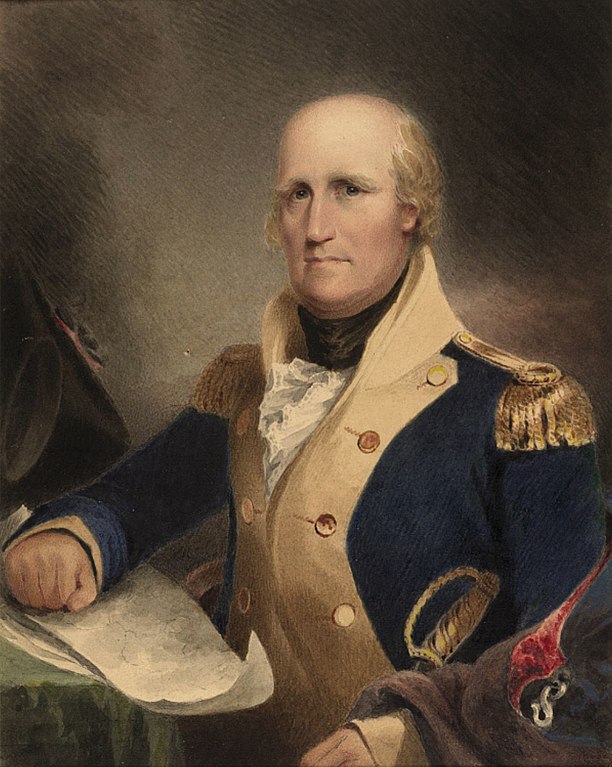

The governor is on the march. Angus McDonald’s village-burning expedition across the Ohio River accomplished more than it appeared at the time: It persuaded Governor Dunmore that more force would be necessary. The governor himself is now leading a force marching west. Another force, under the command of Andrew Lewis of Botetourt County (modern editor’s note: today his home is Salem), is also marching west. They apparently intend to link up somewhere along the Ohio River and then push into the territory on the other side.

By personally leading troops into battle, Lord Dunmore is truly making this his war.

October 1774: Virginia militia defeats Cornstalk at Point Pleasant; Lewis hailed as hero

Victory! We just received word of a decisive engagement on the banks of the Ohio. Those of us long familiar with the back-and-forth of war with the natives had not imagined such a clear-cut victory as this one.

Interestingly, our war-making governor was not part of this action. Instead, the Shawnee under Chief Cornstalk attacked the secondary force led by Col. Andrew Lewis on October 10, near Point Pleasant.

After several hours of fighting, the Shawnee quit the field; the survivors escaped back across the Ohio. At last report, the forces of Lewis and Governor Dunmore were now moving into the Ohio country, with the aim of forcing the Shawnee to sign a peace treaty.

For this victory, Lewis will surely go down into history as one of the greatest Virginians of our time.

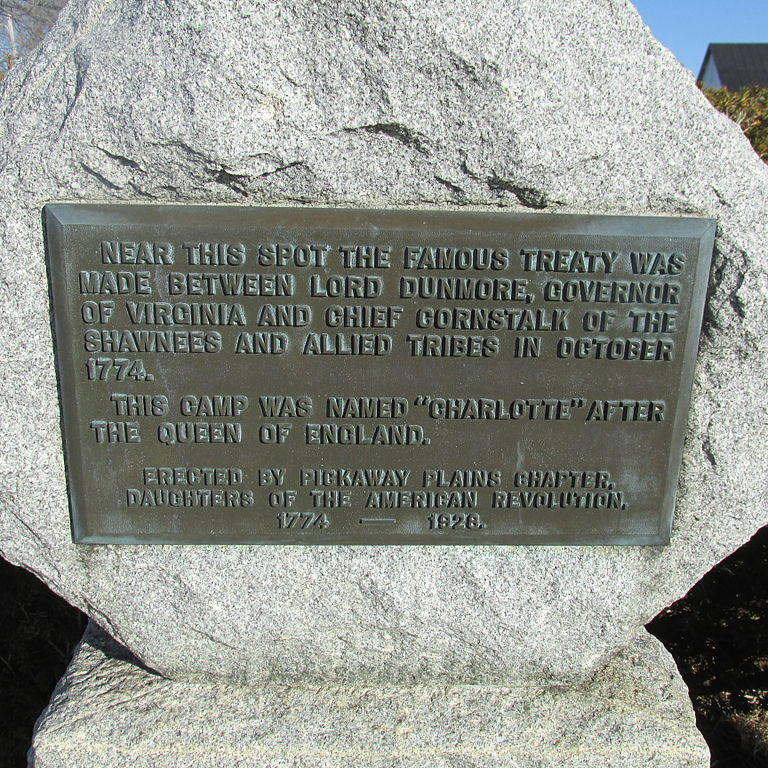

Late October 1774: Treaty signed, more western lands open to settlement

Peace is at hand. For a while, anyway. The governor’s office sends word that the Shawnee have agreed to a treaty that grants all the terms Virginians wanted: The Shawnee will no longer cross the Ohio River to hunt; nor will they interfere with the free passage of settlers up and down that river. The land from here to the Ohio is now open for settlement. Well, maybe. Britain recently awarded Virginia’s western lands to French-speaking Quebec, a controversial move that might block expansion — so the legal status of those lands remains unclear. The one thing in Virginia’s favor: Quebec is way up north, and we already have Virginians living all along the Ohio. The king’s Proclamation of 1763 forbidding settlement in the mountains did not deter those hardy Virginians; this act of Parliament may not either. And now, the Virginia militia has cleared the land of the natives who once called those places home.

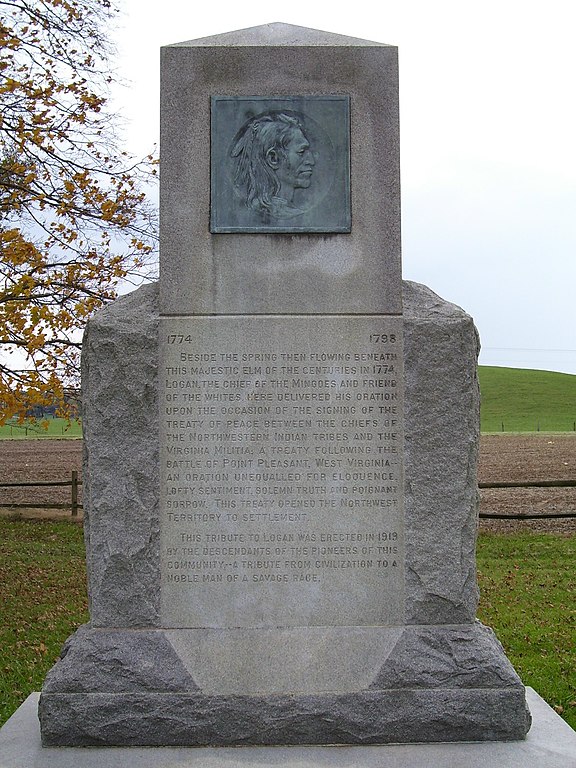

One cautionary note: Simply because the Shawnee, under Chief Cornstalk, have agreed to terms does not mean other tribes have. The Mingo chief Logan — whose daughter was brutally murdered at the outset of this war — refused to attend the parlay at Camp Charlotte in the Ohio country. Instead, he delivered a speech that is being called “Logan’s Lament”:

I appeal to any white man to say, if ever he entered Logan’s cabin hungry, and he gave him not meat; if ever he came cold and naked, and he clothed him not. During the course of the last long and bloody war, Logan remained idle in his cabin, an advocate for peace. Such was my love for the whites, that my countrymen pointed as they passed, and said, Logan is the friend of the white men. I have even thought to live with you but for the injuries of one man. Col. Cresap, the last spring, in cold blood, and unprovoked, murdered all the relations of Logan, not sparing even my women and children. There runs not a drop of my blood in the veins of any living creature. This has called on me for revenge. I have sought it: I have killed many: I have fully glutted my vengeance. For my country, I rejoice at the beams of peace. But do not harbor a thought that mine is the joy of fear. Logan never felt fear. He will not turn on his heel to save his life. Who is there to mourn for Logan? Not one.

Logan has wrongly blamed Michael Cresap for those killings when he should have been blaming the Greathouse brothers, but otherwise, we cannot dispute Logan’s account of things. He and his people were done a great injury, but it hardly matters. When the Mingo refused to accept the same treaty terms that the Shawnee did, Dunmore sent Major William Crawford of Westmoreland County deeper into Ohio, where they came to the Mingo village of Salt Lick Town. The men were absent, off to war, so only old men, women and children remained. Crawford’s force rode into the village and killed all the natives they could find. According to one account, “One Indian woman seized her child of five or six years of age, and rushed down the bank of the river and [swam] across to the wooded island opposite, when she was [then] shot down at the farther bank.” The child escaped into the woods.

Sources consulted: “Virginia, the New Dominion,” by Virginius Dabney; “Forced Founders: Indians, Debtors, Slaves & and the Making of the American Revolution in Virginia,” by Woody Holton; Encyclopedia Virginia, Encyclopedia West Virginia, the Heinz History Center, the Scioto Historical Review.

Other dispatches:

Dispatch from 1774: Britain gives Virginia’s western lands to Quebec

Dispatch from 1774: More than 30 Virginia counties pass resolutions to protest British response to Boston tea-dumping

Dispatch from 1773: Smuggling in Rhode Island prompts Virginia to do something revolutionary

Dispatch from 1772: Britain vetoes Virginia’s vote to abolish transatlantic slave trade.

Dispatch from 1769: Governor dissolves House of Burgesses; Virginia vows boycott of British goods

Dispatch from 1766: A sensational murder at Mosby’s Tavern highlights how much Virginia’s gentry is in debt to Britain.

Dispatch from 1766: In Tappahannock, the Stamp Act prompts threats of violence.

Dispatch from 1765: Stamp Act protest prompts House speaker to accuse new legislator Patrick Henry of treason

Dispatch from 1765: Augusta County mob murders Cherokees, defies royal authority.

Dispatch from 1763: Despite cries of ‘treason!,’ Hanover County jury delivers rebuke to the church — and the crown. (The court case that made Patrick Henry a celebrity.)

Dispatch from 1763: King’s proclamation has united often opposing factions in Virginia (Opposition to the king’s proclamation forbidding western settlement.)

Don’t miss another installment of our Cardinal 250 project. Sign up for our monthly newsletter: