Want to see where the candidates stand? You can compare their positions side-by-side in our Voter Guide. For candidates who haven’t responded yet, you still can. If you no longer have the access link, let us know at elections@cardinalnews.org.

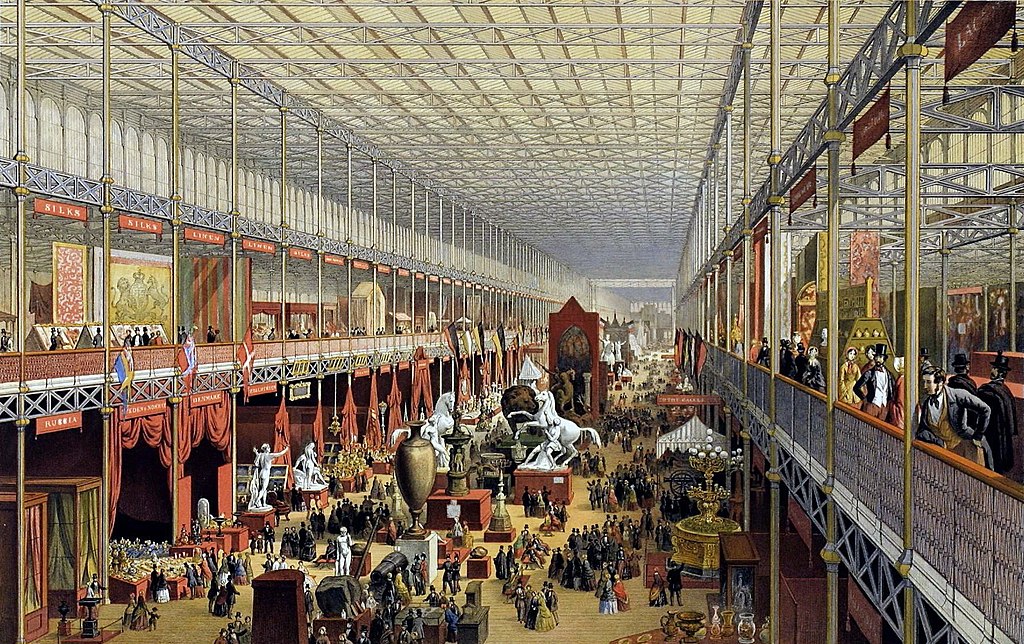

In 1851, London was abuzz with the greatest tourist attraction of its day: The Great Exhibition.

A forerunner of World’s Fair, The Great Exhibition was intended to celebrate the marvels of the industrial age and especially to showcase Britain’s role as the world’s industrial leader.

From May 1 to October 15 of that year, six million people — equivalent to a third of the nation’s population — passed through the pavilions erected in Hyde Park. Some feared such a large throng of people would lead to revolution. “The folly and absurdity of the Queen in allowing this trumpery must strike every sensible and well-thinking mind,” warned one member of the royal family who thought Queen Victoria should leave the city for her safety during the exhibition. The queen thought otherwise; she visited the Great Exhibition three times. Karl Marx, who might have loved a revolution, visited as well and was horrified by what he called “the capitalist fetishism of commodities.”

Among the commodities on display were adding machines that would soon bring a different sort of revolution to the business world. There were cigarette-rolling machines, a device that could print addresses on envelopes, some velocipedes (a precursor of the bicycle) and a vast array of steam engines and agricultural machines. There were some more exotic inventions on display as well — pianos with folding keyboards, which were said to make it possible to listen to music while sailing your yacht, and an umbrella with a stiletto that was said to be purely for “defensive” purposes.

An inventor named William Chamberlain Jr. proudly showed off a more prosaic new creation — a machine that could be used to count votes in an election.

It was deemed less interesting and less practical than the folding piano or the stiletto umbrella and nothing came of it — at least not right away. Still, Chamberlain’s display illustrated a concept percolating in the minds of some creative people in the 19th century — that there must be a way to harness the industrial age to make vote-counting both easier and more honest.

Chamberlain was not the first to invent a voting machine, merely the first to exhibit his mechanism to a wide audience. On both sides of the Atlantic, inventors kept tinkering. In 1875, Henry Spratt of Great Britain received a U.S. patent for his voting machine. In 1881, Anthony Bernanek of Chicago was awarded a patent for his machine. Neither was ever used. In 1888, Jacob Myers of Rochester turned his attention to a voting machine.

Myers had one advantage the other inventors didn’t: He had money and was involved in politics. Myers’ background was in farm machinery, particularly the raking devices used on horse-drawn grain reapers. Later he moved on to safes and bank vaults. His first voting machine combined both those things — a secure, private voting space where a voter could operate a machine with moving parts to cast a ballot.

The political backdrop was a growing reform movement that wanted to clean up the corruption of the notorious Tammany Hall organization that controlled New York’s Democratic Party at the time. One popular reform was the secret ballot; before then, votes were cast in public, sometimes by a voice vote. In some cases, voters were under duress to vote a certain way to maintain their jobs. Others were being paid for their votes. Casting a paper ballot was supposed to fight corruption because it would allow for a secret ballot. Some reformists found that insufficient, though, because casting a paper ballot required a certain amount of literacy. That would disenfranchise many immigrants, whose command of English was poor to nonexistent, but who constituted a larger percentage of the population than immigrants today do. Myers, a reformist Democratic, thought he had a mechanical solution for that: His voting machine, which involved pushing color-coded buttons, meant those who couldn’t read English could still vote.

Myers billed his invention as the “Poor Man’s Voting Machine” and had the wherewithal to promote it as a way to “protect mechanically the voter from rascaldom, and make the process of casting the ballot perfectly plain, simple and secret.” Newspapers praised the invention as the “inventive triumph of its age,” according to the People’s Guide to Rochester. “1890, Rochester investors of both political persuasions provided the capital for the Myers American Ballot Machine Co., and Jacob Myers was elected as president.” Somehow Democrats and Republicans embraced the new device, and in 1892 a bill authorizing its use in town elections — but town elections only — sailed through the New York legislature with bipartisan support.

A month later, in April 1892, the Myers Automatic Booth was used for the first time — in a local election in Lockport, New York, a town of about 16,000 north of Buffalo.

New Yorkers were so thrilled by Myers’ voting machine that in 1894 they approved a constitutional amendment allowing its use in all state elections.

This was a high-tech solution to the age-old problem of cheating. “In the 1890’s, lever voting machines were on the cutting edge of technology, with more moving parts than almost anything else being made,” writes Douglas W. Jones, a retired computer science professor at the University of Iowa who has co-authored a book about the history of voting machines, “Broken Ballots: Will Your Vote Count?”

Alas, Myers and his machine did not have a happy ending. His invention relied on a design flaw — thousands of springs. They wore down with use. When Rochester used his machine for the first time in a citywide election in 1896, the machines malfunctioned. Votes were lost. A losing candidate sued. Myers’ company fired him, his company closed and he went off to the Yukon to search for gold, which he never found. A rival company designed a better machine, one that didn’t rely on springs. The 1898 election went off smoothly and elections have never been the same since — although it did take a while for technology to replace hand-counting in some places. In Virginia, hand-counting persisted into the 1980s in some small precincts in Craig and Highland where it was deemed not cost-effective for the locality to pay for machines.

Earlier this month, two of the three members of the Waynesboro Electoral Board — the two Republican members — filed suit to challenge the constitutionality of the state’s optical scan voting machines, which count the ballots fed into them. The electoral board members’ argument: The state constitution says the ballots shall not be counted “in secret.” Having a machine count the ballots amounts to counting them “in secret,” they argue.

In an email to me, Jones said there were similar concerns when voting machines were originally introduced. “The debate over the legality of lever voting machines in the 1890s was quite similar to the debate over paperless direct-recording electronic voting machines in the first decade of the 2000s. By 1920, most of the arguments against lever machines had been settled and, for the next 50 years or so, we treated them as if they were a fact of nature.”

By the 1930s, “essentially all of the nation’s larger urban centers had adopted lever voting machines,” Jones writes. Virginia, being Virginia, was a bit slower to adopt this technology. A news story in the Northern Virginia Sun in 1940 reports that Arlington County Democrats were debating whether the machines were too expensive. Arlington eventually decided they weren’t. The first use of voting machines in Virginia apparently came in Arlington on Aug. 1, 1950, in a primary election.

Sometime around then Roanoke acquired its first voting machines — which it bought secondhand from Chicago, according to Gilbert Butler Jr., who served as a Republican representative on the city’s electoral board from 1994 to 2006 and served for two years as president of the Virginia Electoral Board Association. Those Chicago machines, which he said were considered “state of the art” in the ’30s and ’40s in Chicago, lasted in Roanoke until they were retired in the ’90s or so. “They were beasts of a machine,” he recalls. He wasn’t sure how much they weighed but their counterparts in New York weighed 840 pounds apiece and had more than 20,000 moving parts. Despite their internal complexity, Tazewell County registrar Brian Earls says “they seemed indestructible.” The fact that they lasted so longer seems to underscore that.

Butler also said they were perfectly accurate. “We had zero issues with them,” he said. Because of the way they operated, they either worked or they jammed — so voters always knew their vote had been cast, or not. Those lever machines may not have been as accurate as we remember. The late Roy Saltman, a computer security specialist for the U.S. government, once produced a report that noted that an unusual number of results on the machine end with “99,” more so than you’d expect with a random distribution. “The probable explanation is that it takes more force to turn the vote counting wheels in a lever machine from 99 to 100, and therefore, if the counter is going to jam, it is more likely to jam at 99,” Jones writes.

We could never know for sure, though, because those machines did not involve an actual ballot. Once the polls closed, poll workers “took the back off — it looked like a piano inside, all the pieces back and forth,” Butler says. Inside were a series of counters for each candidate. “You read it out, just like an odometer,” he says.

That meant whenever there was a recount, the recount simply consisted of making sure poll workers had read that “odometer” correctly. The only exception were the rolls of paper inside if someone wanted to cast a write-in ballot. In 1989, when United Mine Workers leader Jackie Stump mounted a successful write-in campaign for the House of Delegates in Buchanan County and parts of Russell and Tazewell, his campaign was built around the theme of “7Up!” because to cast a write-in vote in that race, voters had to move the 7th lever up to get to the paper.

It was only since the disputed Florida election of 2000, and the computerized upgrades to voting machines that followed, that we’ve seen challenges to the machinery itself. This was understandable with the touchscreen devices that produced no paper trail. That harkens back to an 1890 Rhode Island Supreme Court case that upheld voting machines, Jones says. Justice Horatio Rogers wrote in dissent that the problem with a voting machine that left no paper trail means “a voter on this voting machine has no knowledge through his senses” that he has voted, but rather, must trust that “the machine has worked as intended…” In hindsight, I’m surprised more people didn’t object to lever machines, but they didn’t.

The current election machinery does produce an old-fashioned paper trail — voters pencil in their choices, then feed it into a machine. “We don’t have voting machines,” Gov. Glenn Youngkin has said, “we have counting machines.” Not long after the two Republican election officials in Waynesboro filed their suit, the Republican governor publicized a visit to the Chesterfield County registrar’s office to witness the standard verification of voting machines — the “logic and accuracy” tests that Ben Swenson wrote about for Cardinal last month. The governor pronounced himself satisfied. Nonetheless, the Waynesboro electoral officials say they won’t certify the results unless they’re hand-counted, something not legally possible in Virginia.

Study after study has shown that hand-counts are less reliable than machine counts. “I have looked closely at the demand for full hand-counts that has followed the 2020 election,” Jones said. “I am not convinced of the wisdom of fully hand-counting a U.S. general election. We put as many as 40 races on a ballot, from president to dog catcher, plus lots of judicial retention races. Hand-counting such ballots is quite time consuming and it invites clerical errors. Hand counts work very well in parliamentary democracies like England, where there is only one race on the ballot, member of parliament. In such a race, you just sort the ballots into stacks by how they are voted and then count the number of ballots in each stack. So long as we keep putting so many races on the same ballot, I am convinced that the best way to count is using machines and backing that up with a statistically defensible audit, conducted in public.”

Virginia routinely audits random localities about an election; they’ve consistently shown no problems. Nor do Virginia’s machines connect to the internet, so they’re not hackable by malicious actors, foreign or otherwise. It’s odd that some people are suspicious of a system that has a paper ballot that can be recounted, if necessary, but were not suspicious of those old lever machines that did not.

About a decade ago, New York City had problems with its new computerized machines so it brought 5,100 of the 50-year-old lever machines out of storage to use in a mayoral primary. Virginia can’t do that. I contacted multiple localities to see if they knew what had happened to theirs. All said they’d been sold years ago for scrap metal.

The latest early voting trends, analyzed

My column Tuesday looked at what we know so far. I’ll take another look on Friday in West of the Capital, my weekly political newsletter. You can sign up for that or any of our other free newsletters below: