Confused about Virginia’s cannabis laws? Check out our FAQs.

If you’re looking to buy marijuana at Smith Mountain Lake, just look for the Franklin County Sheriff’s Office at Westlake Corner — the store selling weed is directly across the road.

Yes, it’s illegal to sell marijuana in Virginia, other than through a licensed medical marijuana dispensary. Twice, though, I’ve gone into the Duck In store on the main commercial strip at the lake and bought packets of green vegetative matter that lab tests confirmed was marijuana.

The last round of tests found that the marijuana in question was not only more than 88 times the legal limit in Virginia for the active ingredient that causes the “buzz,” it was also so full of mold and microbes that four doctors I talked to all agreed it could make someone sick if they had smoked it or otherwise ingested it.

If you’re regular readers of this column, some of this may sound familiar. In July, I discovered stores in Abingdon and Marion where I bought marijuana over the counter. In August, I walked into a store in Radford where the clerks “shared” marijuana after I paid $30 for what was deemed about three cents worth of cannabis byproducts.

So how is this Smith Mountain Lake experience different? The stores in Abingdon, Marion and Radford were all set up as “membership” operations. That membership criteria seemed very slight. At the store in Abingdon, I was simply handed a membership card when I walked in. At the one in Marion, I was simply asked for my first name without seeking any verification. At the store in Radford, I was asked to write my name in a notebook — again, with no verification that I was giving a real name.

The store at Westlake Corner was just a straight-up sale, no different from buying a candy bar. Here’s how it all played out — and what this has to say about how Virginia’s murky cannabis laws have opened a door to a black market that’s so open that in places it’s operating on main streets or, in this case, directly across from a sheriff’s office. Virginia is the only state that has legalized personal possession of small amounts of marijuana but bans the sale of said marijuana, which raises the question of how you’re able to obtain this legal product. The answer is a black market that has become increasingly clever — and open — about selling something that’s not supposed to be for sale. The proliferation of “membership clubs” in Southwest Virginia is one way; now there are just straight-up sales under the guise of being something other than marijuana, even though it pretty obviously is.

I was in Franklin County on unrelated business when the topic of conversation turned to my recent columns on those cannabis purchases. I was told that down at the local Exxon station, marijuana was openly for sale in the store. I found this hard to believe but naturally went to check it out. The tip was right.

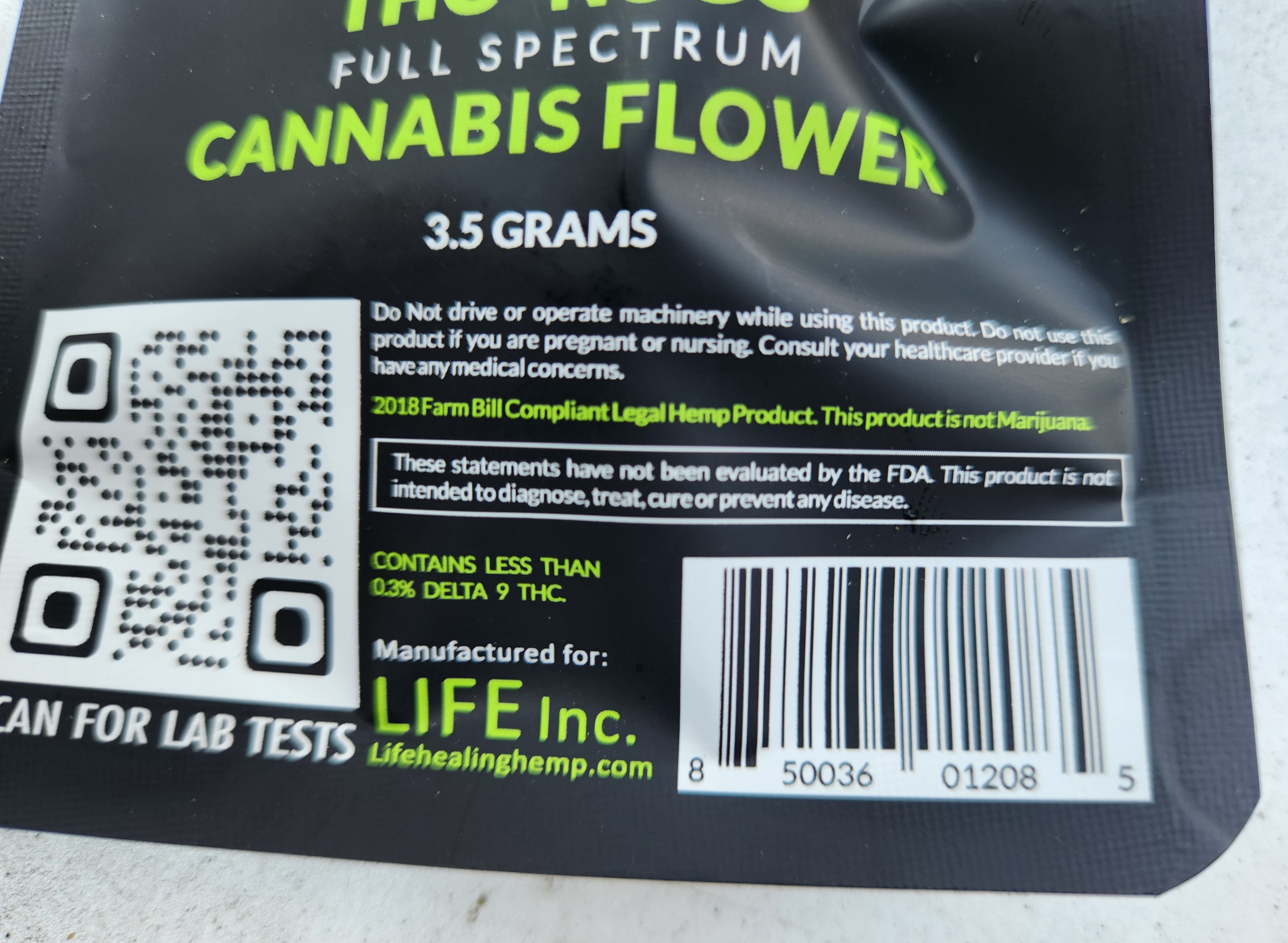

The store was a normal convenience store, unremarkable in any way except for a prize location. At the front of the store, by the cashier but on the customer side of the counter, was a rack of smoking-related supplies. At eye level was a rack of packets of what sure looked like pot. They were advertised as “TCH-A flower.” The back side of the packet said “2018 Farm Bill Compliant Legal Hemp Product. This product is not Marijuana.” It also included a QR code with the notice “Scan For Lab Results.”

I bought two 3.5-gram packets of the Hawk Tuah strain; I was impressed by the marketing savvy someone had to capitalize on that salacious phrase popularized this summer. Each one rang up at $29.99. I paid for this myself because I don’t think Cardinal readers are donating money so that I can buy weed, even if it’s in the pursuit of journalism. The receipt called it “Delta THC blue rhin.” There is a well-known cannabis strain called “Blue Rhino,” although it’s unclear whether that’s what the receipt meant.

Let’s pause here to review the co-mingling of science and the law that explains some of the advisories on the packets.

The 2018 Farm Bill, a piece of federal legislation that was signed into law by then-President Donald Trump, did many things. One particular thing it did was legalize hemp. Hemp and marijuana come from the same plant — cannabis. The difference between the two is how much tetrahydrocannabinol, THC for short, is in the plant. That’s the compound that produces the “buzz.” A cannabis plant with 0.3% or less THC is considered hemp. It has many commercial uses but won’t get you high; in Colonial times, farmers routinely grew hemp as a matter of national security because it could be used to produce rope and sails. Any cannabis with more than 0.3% THC is considered marijuana. Think of it this way: Sweet corn and field corn are both corn, but one we eat off the cob and the other we grind up for cows. This is as if Congress legalized one but not the other.

What Congress didn’t take into account — likely because legislators aren’t scientists — is tetrahydrocannabinolic acid, or THCA. It’s another compound found in cannabis. Unlike THC, THCA won’t get you high. However, it’s easy to convert the non-buzzworthy THCA into the very much buzzworthy THC. How? By heating it. You know, like smoking it.

You can think of THCA as potential THC. It’s as if Congress said it’s illegal for a store to sell food, but you can sell frozen TV dinners on the grounds that nobody can eat a frozen Salisbury steak. Pop it in the microwave, though, and presto, supper. That’s exactly what has happened here. Congress inadvertently legalized marijuana, or, at least, potential marijuana.

The Virginia General Assembly figured this out and classified both THC and THCA as THC for purposes of calculating that 0.3% threshold on whether something is hemp or marijuana. Congress has not, so we have a situation where something that is legal hemp under federal law might be illegal marijuana under state law. That’s why this label is so interesting: It claims the contents are legal under federal law (more on that to come) without referencing the state law. The emphasis on THCA serves as a wink and a nod to those who understand the science. Oh no, we’re not selling you marijuana. Oh no! That would be illegal! But hey, what you do with this when you get home is up to you!

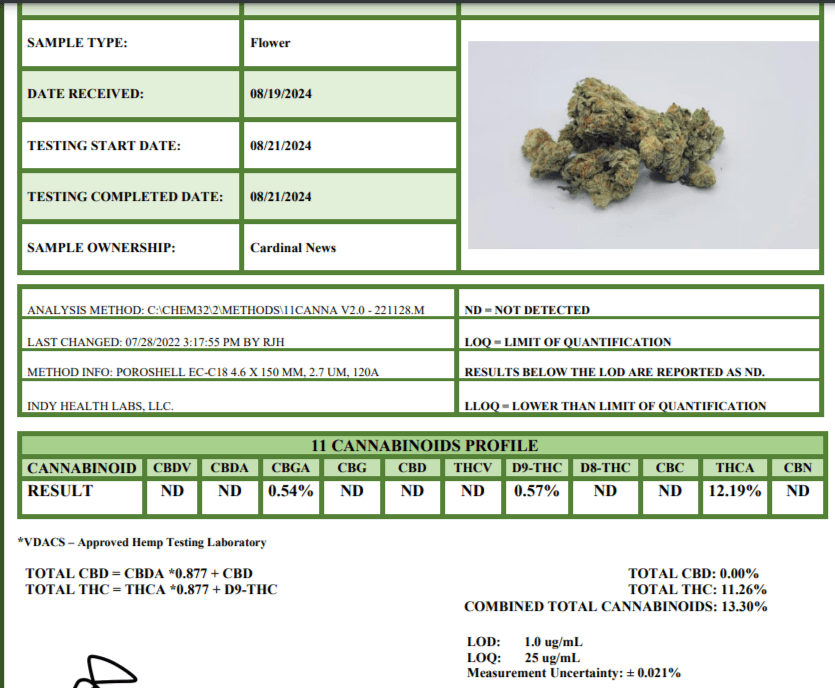

I had both packets tested. Both were, indeed, marijuana.

The one packet tested at 0.57% THC and 12.19% THCA. When you factor in the conversion rate from THCA to THC, the total THC count under Virginia law was 11.26%.

Notice that both the THC-only count and the combined count were over the legal limit of 0.3%.

That means the labeling on this packet was wrong when it said this was compliant with the 2018 Farm Bill and “not marijuana.” Even with the looser federal definition, this packet was over the federal limit and was, most definitely, marijuana.

The second packet tested even stronger.

It tested at 0.79% THC and 13.51% THCA. When that THCA is converted into THC, the total amount would be 12.64%. Again, even without counting the THCA, the packet is over the legal limit to be considered hemp. It’s marijuana.

Virginia law requires that all “edible hemp products … be accompanied by a certificate of analysis produced by an independent, accredited laboratory.” This is typically done in the form of a QR code on the package that, when scanned, links to the Certificate of Analysis.

Both these packets had such a QR code. Neither went to the Certificate of Analysis. Instead, both went to the website of the Hardy-based company listed on the package. That website included dozens of certificates, all of which were out of date (some as old as 2018; none more recent than 2020), and none of which listed this particular strain. All those certificates were from out-of-state labs. I contacted all of them; most replied — and all those said they’d never done business with this Virginia company, that these tests were performed for other companies and, in any case, the certificates are out of date. Some certificates listed a formal expiration date of one year after the test.

Guy Bertuzzi of NV CannLabs in Las Vegas said the 2018 lab report shown on the site from his lab was legitimate — but wasn’t performed for a Virginia company and was actually for a strain called Honolulu Haze, not the Frosted Lime strain this was listed under on the Life Healing Hemp site. Bertuzzi said it’s common for certificates to be pirated and posted on other company’s websites. When I first contacted him, he gave the name of one particular site and asked if this was in regard to that (it wasn’t). He says these copies “are happening all over the country” and are one reason why the legal cannabis market suffers in some states — the black market flourishes because it doesn’t have to pay for the types of tests that legal cannabis firms do.

When I talked to these labs, as well as those in legal cannabis businesses (such as hemp and medical marijuana), I was often asked if we had ordered more extensive tests on the cannabis I acquired. We had not; the lab simply tested the cannabinoid counts to determine the THC levels to see if this was hemp or marijuana.

That led to a second trip to Westlake Corner to buy more weed. I was told I needed 7 grams for a more extensive test. This time the Hawk Tuah strain was gone so, based on name alone, I bought two 3.5-gram packets of the Gorilla Punch strain. The language on the packets was the same as before — Farm Bill compliant, “this is not marijuana” — and included the same QR code that went to the previous, unrelated and outdated, certificates.

Once again, we sent these samples off to be tested. In this case, a more detailed test, which required combining the two packets to get the needed mass.

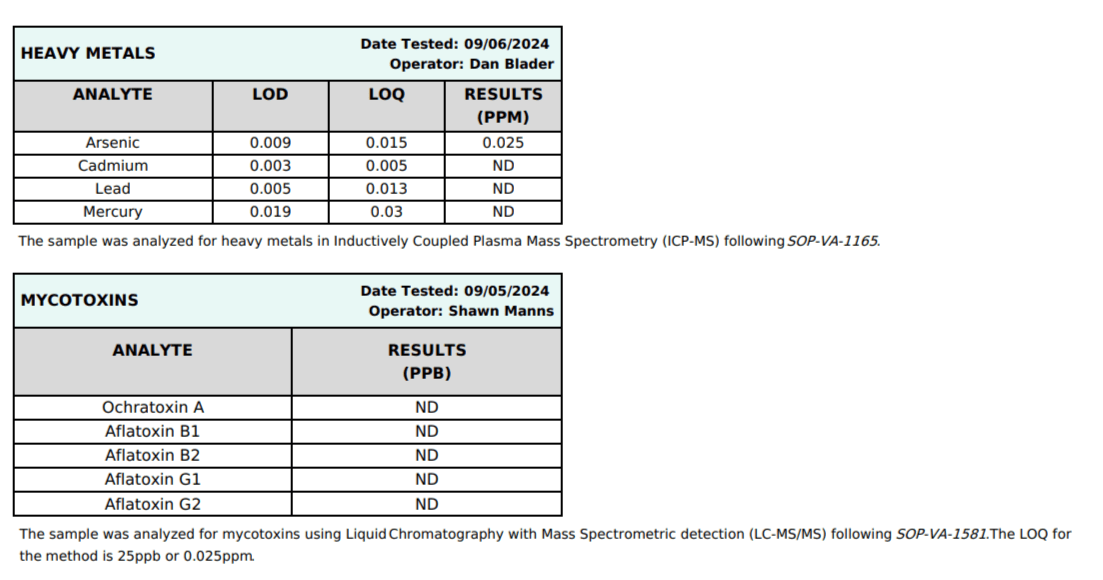

The lab test showed this product was more potent than the previous ones. This, indeed, packs a “gorilla punch” of THC — 3.11%, or 10.4 times higher than the legal limit of 0.3%. The TCHA content was 26.58%. When converted to THC, that would result in a total THC count of 26.51%, or 88.3 times the legal limit.

The lab found no cadmium, lead or mercury, and the sample tested under “actionable” for arsenic. The key word there is “actionable,” not safe.

The FDA sets the maximum amount of arsenic in a tobacco cigarette at 0.1 parts per million; this sample is 0.025, so about one-quarter of what’s allowed. However, the FDA assumes that anyone smoking cigarettes is willing to assume some risk. By contrast, the Environmental Protection Agency sets the maximum amount of arsenic allowed in drinking water at 0.01 parts per million, so this cannabis sample has 2.5 times as much arsenic as what the EPA would let you drink.

It’s the test for mold and microbes that really sets off alarm bells.

In regulating medical marijuana, the state relies on guidance from the United States Pharmacopeia, a Maryland-based nonprofit that specializes in drug information. That group (and thus the state) has set the limit for mold at 10,000 colony-forming units per gram and microbes at 100,000 colony-forming units per gram.

The sample tested at 142,000 cfu for aerobic bacteria — 30% more than the accepted limit if this were medical marijuana.

This sample tested at 131,000 cfu for mold — 13.1 times the accepted limit if this were medical marijuana.

I shared this lab report with four doctors — John Downs of the Virginia Poison Center (affiliated with Virginia Commonwealth University); Chris Holstege, director of the Blue Ridge Poison Center (affiliated with the University of Virginia); David Killeen, medical director of the Intensive Care Unit at LewisGale Medical Center in Salem; and retired health director Molly O’Dell. (Disclosure: O’Dell is a member of our community advisory board, but board members have no role in news decisions; see our policy.)

All agreed that it would be unsafe to smoke or otherwise ingest this sample (which, by the way, was destroyed after testing). The exact details of what might happen could depend on the types of molds or bacteria present; this test didn’t determine those. The health status of the pot smoker also matters, they said. “We know general mold growth can be irritating to upper airways,” Down said, especially those who already have some kind of respiratory condition. “In some people who might be in an immunocompromised state, there might be a risk for inhaling some kind of spores and getting fungal pneumonia.”

“The fungal component is more problematic,” Killeen said. “If you were to burn it, you’d release the components of the fungus or bacteria. If you were to inhale those, those can trigger a response. There are several different lung diseases that you can get from allergic or inflammatory responses. … As pulmonologists, we say all you should be breathing is air.”

Holstege wasn’t surprised. His center routinely tests products. He’s sent people out to buy edible hemp-based products near his office and some have come back with dangerous amounts of hallucinogens in them. The problem, he says, is that these products aren’t tested the way other products are. “It’s a wild, wild west in regard to what is out there with these products.”

So who is this company that’s selling this product that’s labeled as legal hemp but is actually marijuana, which remains illegal to sell in Virginia? Life Healing Hemp is run by Jason Reese. He has a state hemp processing license but said by email that he stopped doing that after Virginia changed the law dealing with how it counts THC. He said now he does no business in Virginia. “We do not sell our products directly to retail outlets,” he said. “All of our products are sold to wholesalers and distributors outside the state. If products are being sold in Virginia stores, they are being brought in from other states without our knowledge.” (When I contacted the Duck-In store and asked who the distributor is for Life Healing Hemp, a clerk, who would not give his name, said the store ordered it online from the company. That website doesn’t show the particular strains I found. It does, though, list various cannabis products such as “THCa Premium Exotic Flower,” which is described as “hot.” That’s a phrase used in the industry to describe hemp that is over the legal limit for THC; Reese said he used the phrase “hot” simply to mean the product is a fast-seller.

Reese said by email that he did not know why the packets I bought tested at levels that would qualify the product as marijuana. “I cannot speak to your test results because I have not seen the laboratory report, do not know the testing methods used, and do not have a chain of custody. All of our hemp is compliant at the time it is packaged. It is possible that the products were mishandled by downstream distributors and exposed to excessive heat and/or light, causing it to degrade and decarboxylate,” he said, referring to the chemical process by which THCA is converted to THC. “These products were exposed to heat after sampling or during storage, this could have triggered the conversion of THCA to Delta-9 THC, resulting in artificially inflated THC results. Improper handling or the application of heat can significantly affect the final Delta-9 THC content in the tested samples. Without documentation showing how the samples were handled from the time of collection to the time of testing, it is impossible to know whether the THC levels reported are reflective of the product’s actual compliance when it left the farm.”

I asked if he could share the Certificates of Analysis he had on the product. He said last Wednesday he would but so far has not.

I talked to multiple scientists and businesses who deal with cannabis, and they said it was highly unlikely that heat during transit or storage would have converted the THCA to THC.

“No, it is not realistic that the heat in transit would convert THCA to THC,” said Michelle Peace, professor of forensic science at Virginia Commonwealth University and one of the state’s best-recognized experts on cannabis. “The temperature has to get to at least 220F, which is why the conversion happens when a joint is lit.”

Shareef El-Sissi, CEO of a hemp company in California, looked at the lab results of the Life Healing Hemp product at Cardinal’s request and said, “It is unlikely that the flower was 0.3% THC when it left his facility. The majority of Type III (High CBD, Low THC) varieties require farmers to compliance test and harvest their crop early to avoid exceeding 0.3% Total THC. The flower in the COA you shared is a Type I (High THC) variety that likely exceeded 0.3% THC in early flowering before the plant matures. It has very little chance of staying below 0.3% THC 30 days from harvest, even less at harvest, and certainly not after all the stem, leaf, and non-cannabinoid containing parts of the plant had been removed. THCA does convert into THC with heat, time, or oxidization. So his response is unlikely to be the cause, but it can be used to possibly explain the current state of the product, and proving his logic to be false beyond a shadow of a doubt requires increasing oversight. The laws, regulation, and subsequent interpretations seem to have left a loophole relating to the potential conversion of THCA into THC. The distributor’s response seemed to have answered the inquiry in a manner that takes advantage of the ambiguity in the rules. … The likelihood that the product you bought was farmed under the hemp regulatory framework is less than likely.”

DorothyBelle Poli, a biology professor at Roanoke College who heads that school’s cannabis program, was more open to the idea that heat during transit or storage could convert the THCA from a legal amount of THC to a non-legal amount. “A company who sells THCA products KNOWS that this is a legal loophole to sell their product and a way to make money,” she said. “And they are aware that THC will convert easily.”

Under Virginia’s current laws, the sale of these products falls into a gray area. The Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services regulates legal hemp; when presented with evidence of products that aren’t hemp, its response is to tell people to contact local law enforcement. Now that Virginia has legalized possession of small amounts of cannabis, and reduced penalties for cannabis generally, it’s a lesser priority for local law enforcement.

Virginia Attorney General Jason Miyares has no power to enforce marijuana laws. However, after Cardinal reported about the other stores selling or sharing marijuana, he sent three of them a letter threatening fines under the state’s consumer protection laws on the grounds that the packages weren’t labeled. Here, the packages are labeled, they’re just wrong. One of those stores, in Radford, has since shut down. The ones in Abingdon and Marion are still open, although now operating under different names. The attorney general’s office did not respond to a request for comment on what happens next.

Earlier this year, Gov. Glenn Youngkin vetoed a bill to legalize cannabis sales, saying he didn’t want to see “a cannabis shop on every corner.” We don’t quite have that. However, even though cannabis sales are illegal, we now have stores selling cannabis on the main streets of some small towns in Virginia — and on the main commercial strip at Smith Mountain Lake.

Let’s talk elections

On Nov. 7, I’ll be hosting a Zoom session to talk about the elections. This is open to all Cardinal News members. Here’s how to become a member.

I also write a weekly political newsletter, West of the Capital, that goes out every Friday afternoon. You can sign up for that or any of our other free newsletters below: