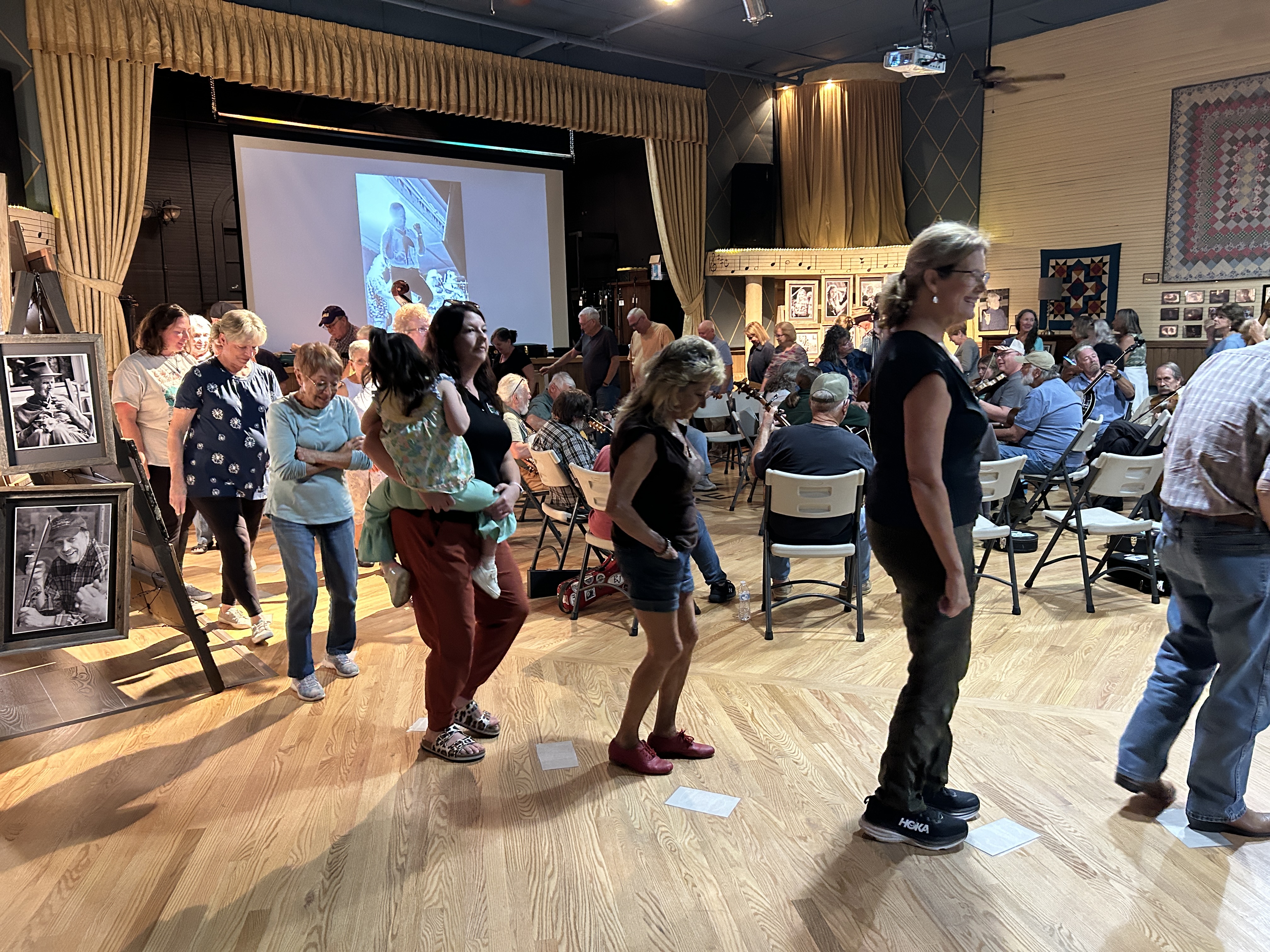

Doris Lawrence and Tom Slusher glided onto the dance floor of the Floyd Country Store as the musicians struck up a waltz.

Fiddlers, guitarists, banjo players and more than a dozen other pickers sat in a wide circle, and a young woman sang the old song “East Virginia Blues,” the group providing a musical backdrop for the dancers.

“I love to dance, I love the music,” said Lawrence, a Floyd native who now lives in the small town of Bridgewater in Rockingham County. She and Slusher are both retired, and they meet in Floyd every couple of weeks to listen to bluegrass and mountain music, dance and travel the backroads of Southwest Virginia.

“I grew up in Montgomery County, where my family were old-time musicians,” said Slusher, who comes to Floyd from his home in Spartanburg, South Carolina. “My mom played guitar, banjo … organ. My grandfather was a fine clawhammer banjo player. Every Sunday, they’d pull out the instruments and play on the porch.”

When they meet in Floyd, the couple attends three or four music events over a weekend. During a recent October getaway, they visited the Floyd Country Store’s Friday Night Jamboree, heard a band play down the road at Wildwood Farms General Store, then returned to downtown Floyd for a Halloween-themed dance on a Saturday night and back again for the old-time jam session at a packed Floyd Country Store on Sunday afternoon. Sometimes, they even travel a couple of hours west to hear music at the Carter Family Fold in Scott County.

“There’s a lot of childhood memories involved for me,” Slusher said. “It’s nice to come back to it.”

That’s music to the ears of the founders and supporters of The Crooked Road, a cultural and economic initiative launched 20 years ago to bring visitors and their money to Southwest Virginia, a region that was hemorrhaging jobs and population as traditional industries — mining, textiles and other factories — shut down or moved operations out of the mountains.

In the spring of 2004, then-Gov. Mark Warner signed a bill passed by the Virginia General Assembly that created the Virginia Heritage Music Trail, an ambitious tourism idea that designated several Southwest Virginia roads as a winding corridor of mountain music, suitably dubbed The Crooked Road.

When Warner visited Clintwood for a ceremonial signing of the bill on May 19, 2004, he was joined by political dignitaries and bluegrass music legend Ralph Stanley, the Dickenson County-born musician who was also honored with a museum bearing his name. Running from Franklin County to Dickenson County, through mountain-music hothouses of Floyd, Galax and Bristol, Warner anticipated that The Crooked Road would bring tourism and economic benefits to the region.

Crooked Road 20th Anniversary Homecoming Concert

Features the Whitetop Mountain Band and the Amanda Cook Band. A panel discussion will include some of the people who helped establish The Crooked Road in 2004.

When: 6:30 p.m. Saturday, Nov. 2

Where: Southwest Virginia Cultural Center, 1 Heartwood Circle, Abingdon

Cost: Free

Information: 276-492-2400, swvaculturalcenter.com

“This trail has unlimited potential,” Warner told The Roanoke Times that day in 2004, a few minutes after he signed the bill. “If we can bring bluegrass fans and fans of traditional country music to Southwest Virginia, then we can persuade them to stay a week and experience everything — our parks, outdoor recreation, culture and crafts. Southwest Virginia has needed that defining hook, and this trail can be that hook.”

Now, 20 years later, supporters of The Crooked Road say that the potential has become a reality. People flock to Southwest Virginia by the thousands every year to attend concerts at the Floyd Country Store and the Carter Family Fold, to eat funnel cakes or perform during the Old Fiddlers Convention in Galax, to dance in the streets during Bristol’s Rhythm and Roots Reunion festival, or participate in or just hang out at any of the many fiddle-and-banjo jam sessions that dot the region like stars in a constellation.

The Crooked Road has become a recognizable brand for the region, and the initiative has achieved measurable economic impact to the tune of $10 million annually, according to a 2015 Virginia Tech report, which is the most recent study of the music trail’s effect on the regional economy.

But supporters also say more work needs to be done to ensure that The Crooked Road remains a draw and an economic generator. More funding from the state is necessary, they say, and The Crooked Road’s partners, from music venues to local governments, must cooperate more closely to promote all the attractions along the musical corridor. Also, even though The Crooked Road positively affects the regional economy, Southwest Virginia has continued to lose population and many jobs over the past 20 years. Efforts to transition the mountainous region from a mining and manufacturing past into an outdoors and mountain-culture future have shown signs of success, with tourism impact reaching $1.3 billion in 2023, according to Friends of Southwest Virginia, a nonprofit that promotes a sprawling area comprising 19 counties, four independent cities and 53 towns.

“The biggest thing that The Crooked Road has done is amplify our cultural assets,” said Dylan Locke, who co-owns the Floyd Country Store with his wife, Heather Krantz.

He said that the founders of The Crooked Road “picked up a megaphone to the rest of the world, [and said] that Southwest Virginia is a place to come visit, and that our musical legacy, the heritage music of this region, is as good a reason as any for people all around the world to come explore what we are all about.”

* * *

‘The music has never stopped’

The Carter Family Fold is part concert hall, part music shrine, all of it housed in a plank-sided building that looks like a shed for hay or farm equipment.

The barn-like amphitheater was built by the descendants of the famed Carter Family — Alvin Pleasant “A.P.” Carter and his wife, Sarah, and their sister-in-law Maybelle — a musical trio that in the summer of 1927 drove down the rutted roads of Scott County to make country music history in Bristol. The Carters recorded songs for the Victor Talking Machine Company for producer Ralph Peer during a recording session so significant, music historians call the resulting records “the big bang of country music.”

The Carter Family became musical royalty, which is why A.P. and Sarah’s children promised to maintain the clan’s musical legacy by showcasing country, bluegrass, gospel and old-time mountain music every weekend inside the rustic amphitheater built in 1974. The venue became a nonprofit in 1979 and hosts concerts on Saturday nights.

Rita Forrester, the daughter of Janette Carter, who died in 2006, and the granddaughter of A.P. and Sarah, now operates the Fold, mostly with some family help and a brigade of volunteers.

“My mother didn’t start out to start a nonprofit; she made a promise to her father to keep his music living on,” Forrester said. Janette’s brother, Joe, built the amphitheater in 1976. The family moved other historic buildings to the site, which included A.P.’s store, now a museum.

Forrester was part of a group of Southwest Virginia tourism officials, local officials, musicians and state staffers who met at the Fold and first hatched the idea of The Crooked Road on a snowy night in 2002. Todd Christensen, a former head of the Virginia Department of Housing and Community Development, and Joe Wilson, a nationally respected musicologist and folklorist, were perhaps the two biggest boosters for promoting regional music and culture as keys to reviving the mountain economy.

“Our objective was to make the region better-known, and find non-natural-resource-based economic development efforts where quality of life is the most important concern,” said Christensen, now retired from the housing and community development department. Wilson, his close friend and primary collaborator, died in 2015.

The region’s musical heritage, he said, was an obvious choice for building a “creative economy.”

The music was already here. The Floyd Country Store’s Friday night jamboree had received international exposure since it started in 1984. The Carter Family Fold and the Galax Fiddlers’ Convention were musical mainstays of the region.

Plus, a pop-culture lightning bolt from the blue had struck the region, when the folksy soundtrack to the movie “O Brother, Where Art Thou?” became an unexpected multi-platinum, Grammy-winning album — a record filled with Southwest Virginia musical connections, from old Carter Family songs, to former Ferrum resident Dan Tyminski’s chart-topping version of “I Am a Man of Constant Sorrow” to songs of Ralph Stanley and his late brother, Carter. The soundtrack shone a Hollywood-sized spotlight on old-time country music, and the music lovers of Southwest Virginia took their bow.

The music of the mountains was ready for its moment.

The Crooked Road idea was unveiled in 2003, and the General Assembly approved the designation a year later. By 2005, a bullhorn of marketing and promotional materials promoted the effort.

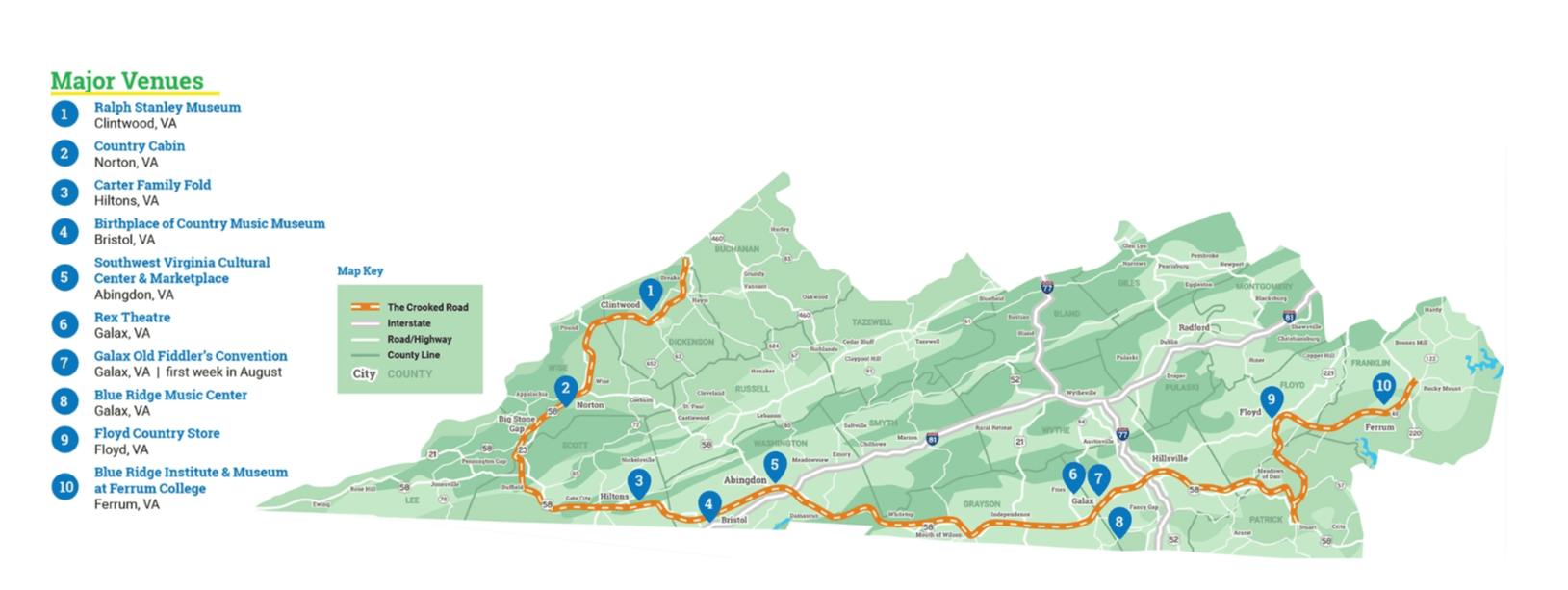

Initially, the virtual musical trail incorporated parts of U.S. 221, 58, and 23 and Virginia 83 and 40, winding a musical path that connected localities like notes on a scale. The Crooked Road cut through nine counties, 10 towns and three cities, bypassing eight “major venues” from Ferrum to Clintwood.

Over the years, more major venues have been added, as well as dozens of affiliated partners, which include local jam sessions, festivals and events not along the primary music trail. Currently, The Crooked Road’s major venues are the Ralph Stanley Museum in Clintwood, the Country Cabin in Norton, the Carter Family Fold, the Birthplace of Country Music Museum in Bristol, the Floyd Country Store, the Blue Ridge Music Center on the Blue Ridge Parkway, the Blue Ridge Institute and Museum at Ferrum College, the Rex Theater in Galax and the Southwest Virginia Cultural Center (formerly known as Heartwood when it opened in 2011) in Abingdon. The music trail runs more than 330 miles from Rocky Mount in Franklin County at its eastern terminus to Breaks Interstate Park on the Virginia-Kentucky border in the west.

Since the trail’s beginnings, supporters have tried to ensure that the music and the people who play it are not exploited in the name of economic gain. Christensen said that The Crooked Road is primarily an economic engine but that the music remains an authentic piece of local culture — he does not want to see the region’s musical heritage commercialized and become a mini-Nashville or Branson, Missouri.

“Joe and I used to argue about this some,” Christensen said. “The Crooked Road is intended as an economic development initiative that uses the region’s best cultural assets — its music, the venues, the festivals — the whole culture is musical.

“Joe was a folklorist and a musicologist with tremendous credentials internationally. We both understood that the music was not to be artificially infected with hillbilly images and the kind of things that have ruined Nashville.”

Christensen said that more state support is needed to keep The Crooked Road viable. The initiative, which is staffed by an executive director and just one other person, operates on grants, plus the $171,250 it gets from the Department of Housing and Community Development each year.

“They’ve run on a shoestring for so long,” he said. “I think the state needs to get behind it with just a little more financial support. Not just new signs along the highway, but real financial support.”

Christensen thinks that the trail’s real economic impact is greater than the $10 million reported by the Virginia Tech study. He said that in the last 20 years, about 25 towns and cities underwent downtown revitalization projects, some of which he credits to the attention that The Crooked Road brought to the region. Some venues received grants to improve their facilities.

In Floyd, Locke and Krantz have spent an untold amount of their own money (they won’t say) on renovating and expanding the Floyd Country Store. After the previous owner, Woody Crenshaw, helped stabilize and remodel the now 114-year-old building in the early 2000s, Locke and Krantz added a café and kitchen and opened a soda fountain and ice cream shop into an adjacent building. They currently employ a mix of nearly 50 full-time and part-time employees, Krantz said.

In addition to the jamboree and jam sessions, the store hosts concerts that include big-name, roots-music performers such as Sam Bush, Bela Fleck and Abigail Washburn, Molly Tuttle and scores of others.

The store was recently named one of “The 20 Friendliest Places in the South” by Southern Living magazine (alongside fellow friendly spots such as the Greenbrier luxury resort in West Virginia and all of Charleston, South Carolina, apparently), whose reporter wrote that:

“The music has never stopped — not since the first person lifted a bow to their fiddle and sent toe-tapping ripples through the Blue Ridge Mountains. … Centuries-old songs spill from The Floyd Country Store’s stage during its weekly Friday Night Jamboree; people groove and boogie with newfound friends, and some may even start flat footing (a dance style that was a predecessor to clogging). Outside, folks often gather in impromptu jam sessions to strum up new melodies.”

The store usually fills to its 275-person capacity on Friday night, with folks visiting from across the United States and beyond. Recent visitors have hailed from Australia, Belgium and Norway, Krantz said, and that was just on a single night. The store gives a cap to the person who comes to the jamboree from the greatest distance — the most recent winner was Hamish MacBeth from Karamea, New Zealand, “a town smaller than Floyd,” he told the owners.

“One thing that’s really interesting to us is that every Friday, we ask, ‘Who’s here for the first time?’ And it’s often half of the room or more,” Krantz said. “We’re getting people each week, visiting for the very first time. That feels really just amazing, bringing that many new people to Floyd every week. I do think The Crooked Road is helpful with that. People do come here to travel the entire road.”

* * *

‘People need to go there’

A circle of dancers sashays around a group of fiddle players, banjo pickers, guitarists and a stand-up “doghouse” bass fiddle player inside the century-old Fries Theatre on a Thursday night. When the musicians suddenly stop playing the old tune “Soldier’s Joy,” the dancers step onto slips of paper strewn across the floor, each piece bearing a number.

A woman hollers, “Does everybody have a number?” Then, she calls out, “Number four!” The dancers check the papers they’re standing on, and a man across the room raises up the winning number — and wins a home-baked cake.

And that’s how you do the cakewalk in Fries.

Fries is one of about 50 affiliated music trail venues, which aren’t part of the main road but get to hang a Crooked Road banner on the wall. From weekly bluegrass at the old Lay’s Hardware in Coeburn to the Friday night jam session inside the Lambsburg Community Center in Carroll County, small community-oriented jams are a big part of local entertainment.

That entertainment can bring money to the region, as evidenced not only by the Virginia Tech economic study in 2015 but by local reports that measure direct effects of local music. In Franklin County, the Harvester Performance Center — a large-scale venue that was created with investment from Rocky Mount taxpayers specifically because Franklin County was the eastern gateway to the Crooked Road — brings $1.1 million of spending activity to town. In Bristol, a 2015 study determined that the Rhythm and Roots Reunion festival created a $16 million impact locally.

That $1.3 billion in tourism-related economic impact in 2023 was a record for Southwest Virginia, according to the Virginia Tourism Corporation, a 10% increase over 2022. Heritage music and The Crooked Road are just a part of that impact in a region that is also attracting more visitors for outdoor recreation such as fishing, kayaking, biking, climbing and other adventure sports.

“Over the last two years, we’ve seen increases in spending in all sectors across Southwest Virginia,” said Tyler Hughes, who became The Crooked Road’s executive director in 2023. “Some of that has to be from Crooked Road marketing. It’s one of the most recognizable brands in the commonwealth.”

The Crooked Road’s familiar logo of a banjo with a green mountain rising in the background laced with a winding road is a part of banners and road signs across the mountain roads.

“It’s probably the most well-known regional thing in Southwest Virginia,” Christensen said.

The 2015 Virginia Tech report did offer a few constructive critiques of The Crooked Road, especially when it came to communication and cooperation of localities spread across 300 miles of mountainous terrain. Some respondents to the survey, which included people who operate businesses or the music venues along the road, wanted advertising to highlight more places in the region and to encourage travelers to explore more parts of Southwest Virginia.

Locke and Krantz both said that they encourage visitors to the Floyd Country Store to continue traveling through the region and attend music events in other locations.

“I tell people to go to the Carter Fold on a Saturday night, even if it competes with something we might be doing,” Locke said. “I mean, it’s the Carter Family. People need to go there.”

Most of the performers along The Crooked Road, from big-name bluegrass acts to pickers at local jam sessions, are white, so reaching out to more diverse groups of musicians and visitors is a priority, Locke said.

The Floyd Country Store frequently books Black performers such as Hubby Jenkins of the Carolina Chocolate Drops, blues guitarist Justin Golden from Richmond and Floyd County fiddler Earl White, making it one of the few venues that brings African American musicians to the stage. Bigger venues such as the Harvester and large-scale festivals, too, bring in diverse acts, which are usually national names.

Locke said that Crooked Road venues need to attract younger people, both performers and visitors, in order to keep the music viable. The store also operates the Handmade Music School, which teaches mountain music to young musicians.

“What we need to look at are ways to get the younger people connecting with this music and understanding their connection growing up in Southwest Virginia,” he said, “and how important it is for them to understand and respect and carry forward their parents’ and their grandparents’ and their families’ traditions so that all these communities stay really grounded and strong because of that.”

With 20 years in the rearview mirror and miles of twisting road stretching ahead, The Crooked Road seems to be on a steady course, still able to attract people to hear real mountain music in the place where that music is rooted. Much of that stability is perhaps because many of the venues existed before The Crooked Road was even a dream. The Floyd Country Store, the Carter Family Fold, the Old Fiddlers Convention and scores of other jams and festivals were around long before there was a Crooked Road to ferry people there.

“We’re 50 years old, we have experience under our belts,” Forrester said. “We hope it will always be here. It’s not just about the music but about the whole culture of Appalachia. You get a good lesson through the music. Appalachian people are warm, kind-hearted and welcoming. People leave here feeling welcomed and learning about the humble roots of this music, and believe me, it was humble.”

This year is one for anniversaries. In addition to The Crooked Road’s 20th, the Carter Family Fold turns 50 this year (and the venue recently welcomed Country Music Hall of Fame member Marty Stuart), the Friday Night Jamboree celebrated its 40th anniversary and the Harvester Performance Center and the Birthplace of Country Music Museum each turned 10.

Music, it seems, is as solid and stable as the mountains where it’s played.

“As everyday lives get more hectic, people want authentic ways to experience culture,” said Hughes, the director who is also a Big Stone Gap town council member and a fine old-time musician. “What has made The Crooked Road last is that our venues showcase something that can’t be replicated anywhere else.”

Back at the Floyd Country Store, where Tom Slusher and Doris Lawrence took a break from the dance floor, Slusher (who has also been to the Carter Family Fold at least a dozen times, he said) gave another reason for why the music still draws people together.

“It’s relevant because it’s fun,” he said. “It’s entertainment. Life is meant to be fun, and here is a place where you can go out and have it.”