Segregated Clifton Forge could be a scary place for Black kids like Ettrula Clark Moore.

Racist insults and rocks were often hurled at them while biking down certain streets. They couldn’t eat at downtown restaurants, had to sit in the “colored sections” of movie theaters and train cars. And when the Clifton Forge High School band played “Dixie” and its wish for “the land of cotton,” they had to stand.

But there was one nearby refuge where the fear and anxiety could be set aside just like the psalm that likely gave it its name.

Amid the wooded trails where children could scream and scamper, the flowered fields perfect for picnicking, the white-sanded beach and glassy lake mirroring the far-sided mountains, Green Pastures indeed restored their souls.

Today, a group of Clifton Forge citizens — joined by federal and state agencies, Virginia Tech and the national Mellon Foundation — seek to restore Green Pastures Recreation Area to its former glory and memorialize its history as the first and only federal recreation site open to African Americans in segregated Virginia.

“We stand on the shoulders of our ancestors, our predecessors, and they paved the road for us,” said Moore. “I am so thankful for those people who were courageous, persistent, who campaigned, and they campaigned in a dark era, so that we and they succeeded.”

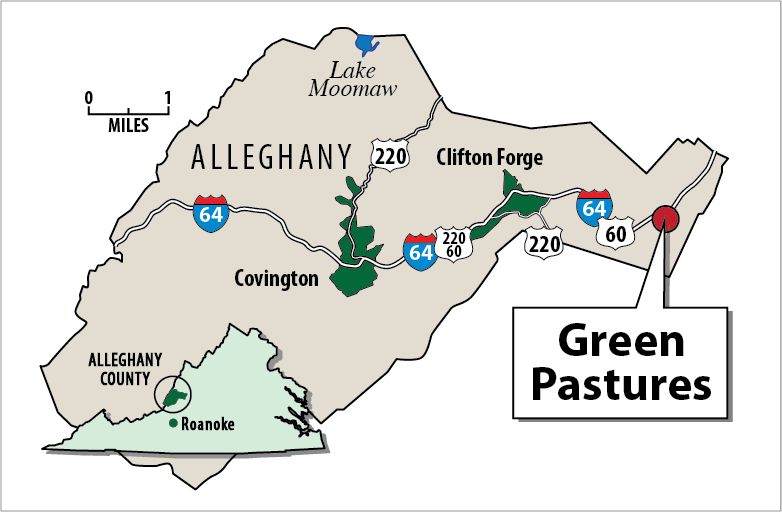

Located in the Alleghany County community of Longdale, Green Pastures was created in response to one of many injustices Black Americans faced in the segregationist South.

In 1936, Virginia opened its first six state parks, among them nearby Douthat State Park. Only whites, though, could enjoy the public facilities — not surprising for Clifton Forge’s African Americans who had long before achieved self-sufficiency by creating their own thriving community of businesses, schools and churches.

Among their leaders was Moore’s uncle, the Rev. Hugo Austin, pastor of First Baptist Church, who, during World War II, would enter the U.S. Army, rise to the rank of lieutenant colonel and eventually be laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery. But, in 1936, he was an organizer of the Clifton Forge NAACP, which petitioned the U.S. Forest Service to create a recreation area for African Americans in the George Washington National Forest.

Despite some grumbling from local whites, the Forest Service requested a company of Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) workers to cut hiking trails, dig a beach, build a dam to create a man-made lake, and erect bathroom facilities and a picnic shelter.

On June 15, 1940, Green Pastures Recreation Area opened.

Today, sitting inside the stout-timbered shelter, Pamela Marshall, Clifton Forge’s former mayor and a force behind the restoration, closes her eyes as she remembers her childhood. “I can feel the ancestors,” she says. “When I’m here, quiet and meditating, I can feel them. And I think I can almost hear the laughter of the children. When you would turn off that main road and all you heard was kids giggling and screaming and running, it was just an awesome experience.”

Walking along a wooded trail dappled by autumn leaves of red and gold, and emerging onto the grassy field that rims a now-weeded beach, Gregory Key recalls Green Pastures being the one place where his father felt free.

“Most of our fathers worked on the railroad, so they were pretty stern, hard men,” Key said. “So to be a little kid and see your dad jumping out there in that lake like a little kid, that was exciting to us. We probably didn’t see that side of him till we came down here.”

For Moore, a trip to Green Pastures “was like for a child today going to Disney World. We did our end-of-the-school-year trips here, and we would get outfits — big, special outfits — to come here at the end of the year.”

Local residents weren’t the only ones who came to enjoy its Psalm 23 blessings of green pastures and still waters. Black families journeyed from Richmond, Norfolk, Washington, D.C., and beyond, said Josh Howard, a history consultant with Passel LLC who has helped with the Green Pastures preservation.

“I believe it is the first and only entity of its kind in the Forest Service and likely the federal parks system,” Howard said.

But Green Pastures’ distinction was short-lived. In 1950, the federal government desegregated the area even though Virginia wouldn’t desegregate its state parks for another 14 years. Concerned that some citizens still thought Green Pastures was only for Black visitors, in 1964 the Forest Service rebranded the park to “Longdale Recreation Area” to attract more white visitors.

By the 1980s, most white people who visited didn’t know the park’s racial history. Among them was Joan Vannorsdall, a transplant from Connecticut, who would bring her children to the park to swim and learn about snakes. “I knew nothing about the segregation history of this park, less than nothing. I thought it had always been here, this beautiful place.”

In the decades that followed, maintaining that beauty took a toll on the Forest Service, and in 2017, the park was closed.

But while the federal and state governments were at odds in the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s, they came together starting in 2020 to reopen the park. Petitioned by a “Save Green Pastures” campaign, Gov. Ralph Northam announced plans to allow Douthat State Park staff, under Virginia’s Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), to steward the park with the consent of the Forest Service.

“I think a lot of people look at DCR, and they think of the natural resources,” said Douthat State Park ranger Adam Bresnehan. “But look at the cultural resources. I mean, that is just as significant and as easy to lose as the natural resources are. These special places that have cultural significance … it’s paramount to what the mission of state parks and DCR is.”

With the reopening in 2021 came the renaming back to its original Green Pastures.

“I call it a miracle in the mountains,” said Marshall. As a retired FBI employee in Washington, D.C., Marshall said, “I know how difficult it is to get things moved through, and the fact that this was federal, local, state governments coming together, to do this in a four-year time was a miracle to me. And now I’m calling this portion, this iteration, ‘Green Pastures 2.0’ … the gift that keeps on giving.”

Howard the historian is more cautious in his optimism: “I do think it’s a shame that the Forest Service, starting in the 1980s basically didn’t give it the attention that it deserved. I really hope Virginia state parks take this seriously and invests the money in the people that it serves.”

But not just governmental agencies are now involved.

In 2022, Virginia Tech professors Emily Satterwhite and Katy Powell received a $3 million grant from the Mellon Foundation to create Monuments Across Appalachian Virginia (MAAV) to memorialize important histories of underrepresented populations.

Green Pastures has been awarded $217,000 of that MAAV grant to fund three initiatives:

• A staged reading of a new play by Lynchburg playwright Royal Shiree.

• An interpretive trail featuring benches and seven markers sharing Green Pastures’ history.

• Preservation of the CCC-era picnic shelter.

Thirty-five citizens attended a listening session on Oct. 21 to share their Green Pastures memories with Shiree to capture for her play.

“It was so overwhelmingly positive,” said Marshall. “We had people singing, we had people sharing family stories. And it was just so wonderful to see the people, which is exactly the purpose.”

Once shunned by whites-only Clifton Forge, the town’s complicated African American history is now embraced, said town manager Chuck Unroe.

“I remember Green Pastures being here when I was a child, but I also was involved very early in my career when the Friends of Green Pastures, and Mayor Marshall at the time, were involved in getting this park re-recognized and reopened and brought back to the public’s eye. And promises were made and commitments were made, and then very shortly after that grand reopening, it was forgotten again, and it fell back to not being accessible, not being usable, and that really bothered me. And when we had this opportunity [with the MAAV grant] we thought, we can bring it back to the forefront, re-invest, get new interest in the park, and bring it back so that the memories are there, and most importantly, the history is accurately told.”