The year 2026 marks the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Cardinal News has embarked on a three-year project to tell the little-known stories of Virginia’s role in the march to independence. As part of this, I will be writing monthly columns about the politics of the era, written the same way I’d write them today. The events described here took place in 1774.

Across Virginia, from the Atlantic Ocean to the Ohio River and beyond, the leaves are falling.

The season is not the only change in the air.

We are still coming to grips with the implication of last month’s military victory over the Shawnee at Point Pleasant on the banks of the Ohio and the subsequent peace treaty that Governor Dunmore forced the natives to acquiesce to.

In one stroke, two of the most objectionable actions from London have been undone — if not in law, then at least in practice. I refer, of course, to the king’s infamous Proclamation of 1763, which forbade settlement west of a certain line that ran through the mountains, as well as this year’s Quebec Act, by which Parliament took those lands away from Virginia (and other Colonies which also laid claim to them) and assigned them to French-speaking Quebec.

Now, with the Shawnee and other tribes in retreat, Virginia is free to colonize the Appalachians and beyond, no matter what the government in Great Britain has to say. That raises a tantalizing question: What other edicts from Great Britain might we be free to ignore?

That brings us to discussion of the historic event that just concluded in Philadelphia — the Continental Congress, the first-ever gathering of Colonial representatives of 12 of Britain’s 18 North American Colonies. Georgia did not send a delegation; neither did East Florida, West Florida, Nova Scotia, Quebec and Saint John’s Island. (Modern editor’s note: The latter is now the Canadian province of Prince Edward Island.) All have been invited to an expected second Continental Congress, but we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

The impetus for this gathering was, of course, Britain’s reaction to the Colonial reaction to the Tea Act of 1773, which was a British reaction to the Colonial reaction to the Townshend Act, which was a British reaction to, well, many things. Year by year, events seem to be spiraling out of control. After the French and Indian War, Great Britain has sought to force Colonists to pay more toward their own security — security that many don’t think we need and certainly not through taxes that we didn’t impose on ourselves. After the British Parliament passed the Tea Act, some hot-headed Boston agitators boarded a ship in the harbor and tossed the tea overboard. In response, Britain’s navy set up a blockade of Boston Harbor and passed yet another series of laws which have come to be known simply as the Intolerable Acts. The first of those, the Massachusetts Government Acts, attempted to strip the Colony of self-government, even to the point of limiting town meetings to one a year. That has alarmed Colonists far beyond Massachusetts for fear that their rights might be targeted next. Subsequent acts, indeed, applied to all the Colonies — including the Quebec Act that tried to put western lands under the control of Quebec’s appointed administrators, and thus indirectly under the control of the king.

If Britain is going to treat all the Colonies this way, then all the Colonies must respond together; at least that’s the thinking behind the Continental Congress. At issue here is a philosophical question: Who has the right to tax Colonists? In Britain, only the elected House of Commons can levy taxes. That’s considered a fundamental right under the English Bill of Rights. Did Englishmen lose their rights when they sailed across the Atlantic? If no, then why are these taxes forced upon us when we did not elect representatives to Parliament? If yes, then we have a more dangerous situation than merely taxes we don’t like.

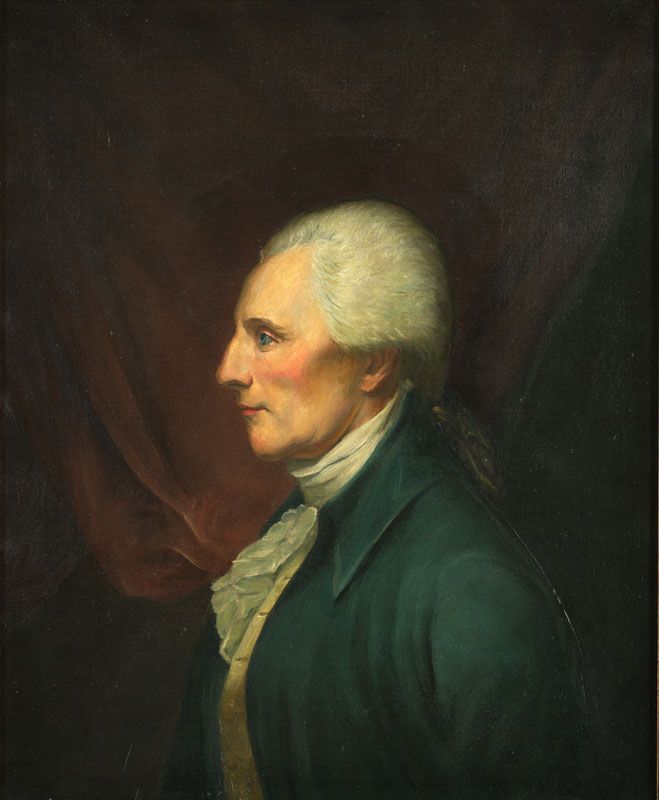

We have no precedent for what is now transpiring. The only thing we can say for certain is that the Colonies represented in Philadelphia sent high-level delegations. For Virginia, that included seven of our leading men, who do not always agree among themselves: Richard Bland of Prince George County, Benjamin Harrison of Charles City County, Patrick Henry of Hanover County, Richard Henry Lee of Westmoreland County, Edmund Pendleton of Caroline County, Peyton Randolph of Williamsburg and George Washington of Fairfax County.

Massachusetts’ delegation included two of its citizens whose names are now well-known throughout the Colonies: John Adams and Samuel Adams.

In a sign of the respect with which Virginia is held, the delegates named Randolph as their president; he served until ill health forced him to give up the post.

As welcome as this gathering was, it’s also clear that the delegates were not of one mind. All agreed that Britain’s acts are, indeed, intolerable, but they disagreed on how to change them. Some looked for ways to persuade London to relent; others — including Virginia’s outspoken Henry — pushed for a declaration of Colonial rights. Henry, who has often found himself in the minority in the House of Burgesses in Williamsburg, was in Philadelphia in the company of many like-minded men. Some might call these men radicals. Roger Sherman of Rhode Island publicly proclaimed that the British Parliament has no authority over the Colonies; Henry jumped to the next logical step — if Parliament has no authority over us, then we must form our own government. That comes dangerously close to suggesting the Colonies declare themselves independent of the king altogether, although no one went that far (and Henry has risked being called a traitor before for his vocal defense of American rights).

The Continental Congress did not resolve those issues, but it did agree on something that may be almost as incendiary: It voted to organize a boycott of all British goods — and to halt exports of many, although not all, American goods.

We’ve had occasional boycotts before: In fact, this Continental Association is modeled after the Virginia Association of 1769, in which Virginians boycotted British goods. (Another sign of Virginia’s influence in this Congress: The proposal for the boycott was introduced by Richard Henry Lee.) We know one consequence of that boycott: It meant more work for Virginia’s women, both free and enslaved, who were called upon to produce clothing that otherwise would have been imported. You may recall I discussed this in a previous dispatch. Wool won’t spin itself.

The Congress made two important exceptions to the ban on exports, both of which show how difficult it is to get these fractious Colonies to work together — and which call into question whether any of this will work in forcing Britain to heed the Colonies’ demands.

Virginia delegates were responsible for the biggest of those exceptions: They were successful in delaying implementation for one year. Why? Simple. Virginia’s farmers are making a good living exporting tobacco to Britain and grain and firewood to the West Indies, where the former is used for food and the latter is used either to light the fires that boil down sugarcane or build the barrels that sugar (along with molasses and rum) is shipped in. Some might argue that we have put profit ahead of politics.

There’s good reason to question whether this one-year delay in implementing non-exportation renders the whole scheme moot. If we cut off all exports now? The West Indies would have felt an immediate pinch. Without grain, the British masters there would not be able to feed their enslaved laborers, and the masters there always live with the fear of a slave revolt (as do some here in Virginia, for that matter). They could have shifted their enforced laborers to growing food instead of sugarcane, but that would have cut into their profits. All this would have eventually been felt back in Britain. Instead, we have given the British, be it in London or the West Indies, a year to figure all this out.

Virginia’s tobacco farmers will not suffer, either way. Tobacco prices now are low, and some have argued they should shift to other crops, such as hemp or flax, which farmers could just as profitably export to Europe. Meanwhile, South Carolina wrangled an exemption of its own — that Colony can continue to export its indigo and rice to Britain.

With all those loopholes, it’s unclear whether these economic actions will have any impact. Of course, there are those who argue whether the Virginia boycott in 1769 had any impact. British exports declined, but the merchants involved seemed much concerned; many found ways to circumvent the ban. Britain did lift the Townshend Acts on everything but tea, although that took two years.

It’s now 1774. If this takes two years to have an impact, where will we be in 1776?

Sources consulted: Encyclopedia Virginia, “Virginia: The New Dominion,” by Virginius Dabney, “Forced Founders: Indians, Debtors, Slaves & The Making of the American Revolution in Virginia,” by Woody Holton.

Other dispatches

Dispatch from 1774: Settlers massacre Mingo near Ohio River, prompt ‘Lord Dunmore’s War’

Dispatch from 1774: Britain gives Virginia’s western lands to Quebec

Dispatch from 1774: More than 30 Virginia counties pass resolutions to protest British response to Boston tea-dumping

Dispatch from 1773: Smuggling in Rhode Island prompts Virginia to do something revolutionary

Dispatch from 1772: Britain vetoes Virginia’s vote to abolish transatlantic slave trade.

Dispatch from 1769: Governor dissolves House of Burgesses; Virginia vows boycott of British goods

Dispatch from 1766: A sensational murder at Mosby’s Tavern highlights how much Virginia’s gentry is in debt to Britain.

Dispatch from 1766: In Tappahannock, the Stamp Act prompts threats of violence.

Dispatch from 1765: Stamp Act protest prompts House speaker to accuse new legislator Patrick Henry of treason

Dispatch from 1765: Augusta County mob murders Cherokees, defies royal authority.

Dispatch from 1763: Despite cries of ‘treason!,’ Hanover County jury delivers rebuke to the church — and the crown. (The court case that made Patrick Henry a celebrity.)

Dispatch from 1763: King’s proclamation has united often opposing factions in Virginia (Opposition to the king’s proclamation forbidding western settlement.)

Don’t miss another installment of our Cardinal 250 project. Sign up for our monthly newsletter: