Dozens of residents packed into a room at the Christiansburg Library on Thursday for a meeting on the effects of Hurricane Helene-related flooding on the Radford Army Ammunition Plant.

As the evening wore on, some became frustrated with what they were hearing: Toxic chemicals had washed from the plant into the New River, and this was the first they’d learned of it, six weeks after it happened.

“This isn’t how you inform the public,” Georgia Doremus said, interrupting a U.S. Army representative.

Her words were directed at a handful of representatives from the Radford Army Ammunition Plant; BAE Systems, a government contractor that operates the plant; and various environmental agencies, who sat at the front of a room that had been filled with a few dozen members of the community. It was the first time the group had addressed the public directly after the remnants of Hurricane Helene devastated the region with widespread flooding and wind damage in late September.

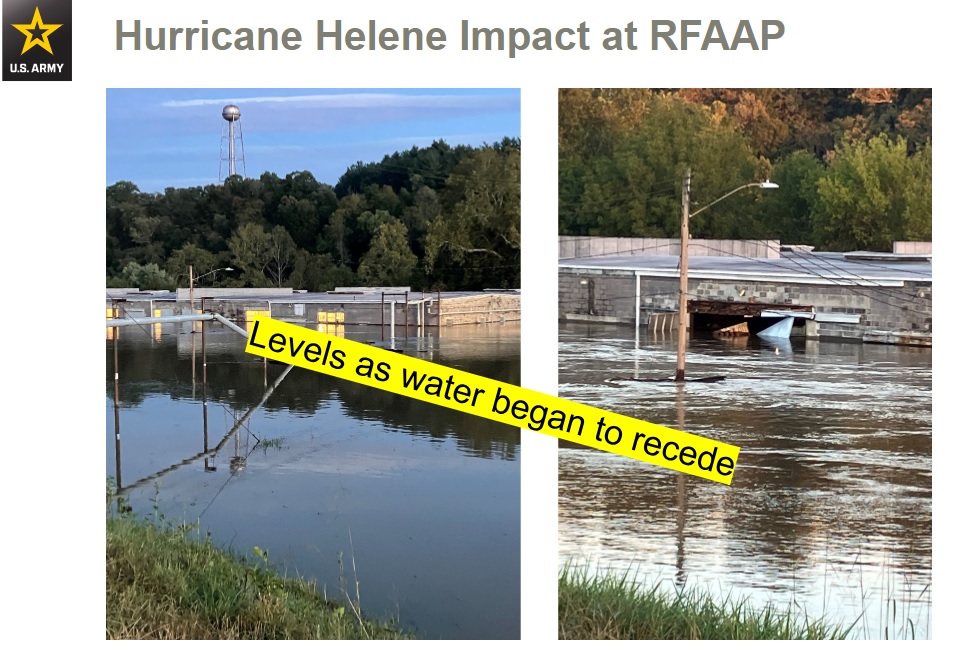

Floodwaters ripped open the doors of a warehouse at the Radford Army Ammunition Plant — known locally as the arsenal — and swept 13 containers filled with toxic material into the New River in a 31-foot storm surge. Tens of thousands of pounds of wastewater used to create munitions at the plant was said to have been released into the river.

“I’m furious,” Doremus told the panel earlier that evening. “I can’t believe it took you a month to tell the community about this.”

What was in those containers, and why are residents concerned?

Each of the 13 tanks contained 275 gallons of dibutyl phthalate, a clear, oily liquid used to make rocket fuel. The National Toxicity Program’s Center for the Evaluation of Risks to Human Reproduction has said it’s an endocrine disruptor, connected to decreased fertility as well as liver and kidney toxicity. It’s been deemed hazardous by the Environmental Protection Agency.

As of Monday, four containers, also called totes, had been located, two of which were damaged and had released their contents.

That means there could be 3,025 gallons of DBP waiting to be found along the river, either sealed safely in the barrels or potentially free-flowing in the waterway or on the bank.

Carla Givens, environmental director with BAE Systems, said the floodwaters washed wastewater containing calcium sulfate back out with it — 127,500 pounds of water that had not yet been deemed safe to be discharged into the river. She also said there’s a possibility that up to 700 gallons of diesel fuel were released from tractors and emergency generators that were submerged in the flood.

Three chemicals were released in the late-September flood: petroleum, calcium sulfate and dibutyl phthalate. The dibutyl phthalate is expected to sink to the bottom of the river, which means bottom-dwelling aquatic animals are most likely to be affected by its presence in the river, Givens said.

Calcium sulfate can cause irritation to eyes, skin and the upper respiratory system, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Residents said they were not notified of the incident until Thursday evening’s community meeting, one of a few held by RAAP on an irregular schedule each year.

“While they were touting their community service functions, they ignored repeated calls to inform the community of their functions and failures,” said Alan Moore, a resident who attended the meeting. “To me, it was another infuriating meeting with a government facility that shows no regard for the community they’ve operated in for over 80 years.”

The facility was fined by the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality a number of times, including in 2024, 2023 and twice in 2012 for releasing “excessive levels of toxins” into the New River. The Radford plant was reported to be the facility that released the highest amount of toxic chemicals into the air, water and land in 2022, according to a report released by the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality in 2024.

Community members speak out

Sarah McGee, who lives one house away from the river, said she learned of the missing totes “by chance” at that Thursday community meeting.

At the meeting, she asked whether it’s safe for her grandkids to play in the river. She said she didn’t receive a direct answer.

“I want us to be safe,” McGee said. “I love that river, and our family has a deep appreciation for that environment.”

At Thursday’s meeting, Givens said that the situation was reported to Virginia’s Department of Environmental Quality, as required by law.

Irina Calos with the DEQ said residents are advised to avoid floodwaters and flooded areas. She said the DEQ has not implemented any special water quality monitoring associated with the impacts of Hurricane Helene.

“Any contamination that has been released from the totes has long washed down the river, such that we do not expect any long-term negative impacts to water quality,” she said in an email.

As far as notifying the community goes, Calos said state law requires DEQ to share information “when the Virginia Department of Health determines that the discharge may be detrimental to the public health or the Department determines that the discharge may impair beneficial uses of state waters.”

When nature overwhelms planning

Givens said during the meeting that though some precautions had been taken prior to the storm, the 13 chemical barrels left in the warehouse were “predicted to be not impacted substantially.” They were later submerged in the storm surge.

She said requirements to notify emergency agencies of the chemical release were executed during flooding, and there is “no reason to believe public health was jeopardized.”

Givens said BAE has contracted with drone companies to fly over the site, as well as helicopters and vehicles to search all the way to West Virginia for the missing barrels. She said that so far, they’ve seen no typical indicators of environmental impact: no fish killed or decrease in vegetation along the river.

That didn’t fly with community members during Thursday’s meeting.

Kellie Ferguson, a mother of five and member of the group Citizens for Arsenal Accountability group, said questions posed to the panel during Thursday’s meeting about potential health and environmental hazards were left unanswered. She said the CAA group will meet later this week to debrief after finding out about the missing totes.

“They continually downplayed the situation,” she said. “Community members came to the meeting looking for answers and only left with more questions and confusion.”