The extent of the damage to Ralph Wilson’s businesses didn’t hit home until after floodwaters brought by Hurricane Helene to Damascus had begun to recede. He had been stuck outside of his home, which had doubled as a bed and breakfast, during the storm.

“I learned, I think the next day, that the doors had blown off my diner and water rushed in and just tossed all the equipment. It was just beyond belief,” he said.

Wilson owns four businesses in Damascus, a small town nestled in the Appalachians near the Tennessee border. Damascus Diner was his main moneymaker. It was also his business that sustained the most damage of the four.

Floodwaters swept into the cellar of the Dragonfly Inn — his bed and breakfast, as well as his home — and knocked out support beams, forcing that business to close. He also owns a coffee shop called Main Street Sweets and Eats and Wilson’s Cafe and Grill. Wilson’s sustained minimal damage and is the only business of his that remained open after Helene.

Before Helene, Wilson employed 40 people across all of his four businesses. After Helene, his workforce is down to 20. His employees helped to clean out the mud and cooked food for the community for more than a week while the area was without power and water.

Michael Wright also owns four businesses in Damascus: Adventure Damascus, Hellbender’s Cafe, Damascus Outfitters and a screen-printing shop. Adventure Damascus, his most profitable business, had been open since 1998. It relied heavily on traffic and tourism from the Creeper Trail, a bike trail that runs from Damascus, through the mountains and Abingdon to the North Carolina border.

Helene-related flooding destroyed 18 trestles on the trail and washed away much of the path, and all of Wright’s businesses, which employed 47 people total, followed like dominoes.

In the days after the storm, Wright went to a recovery center that was set up by the Federal Emergency Management Agency in the area to see if assistance was available to him as a small-business owner to help him rebuild and reemploy his workforce

He was told that he could get a loan with between 4% and 8% interest from the Small Business Administration but that the agency didn’t have any money left to give due to a lapse in Congressional funding. The agency had warned Congress prior to Oct. 15 that funds in its disaster loan program would be exhausted following increased demand from Hurricane Helene.

“I just put the SBA out of my mind and started cleaning up and trying to resurrect my business,” he said.

When Wilson learned the SBA had run out of money to support small businesses as they recovered from Helene, he began paying his remaining employees out of his own pocket and worked to seek help elsewhere.

Together Wright and Wilson laid off 67 employees in a town of about 700 people.

What happened on the floor of the Senate on Nov. 14?

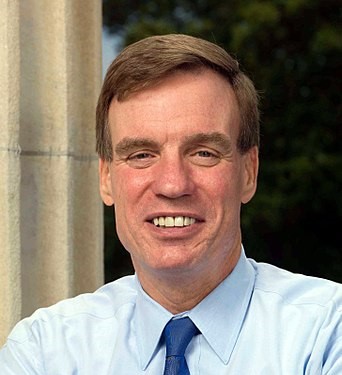

In an effort to fast-track relief to small businesses in the wake of a “first-of-a-kind storm,” Sens. Thom Tillis, R-N.C., and Mark Warner, D-Va., took a bill that had already passed the U.S. House of Representatives, added text to provide money to the SBA for Helene recovery, and attempted to pass it through the Senate by unanimous consent on Nov. 14.

“Unanimous consent” means exactly what it sounds like: It’s the agreement of all 100 senators to do something, and if no one affirmatively objects, that thing happens. The Senate often uses the tactic to process noncontroversial items because it’s faster than the Senate’s regular mode of operation, said Molly Reynolds, a senior fellow in governance studies at the Brookings Institution.

The effort to fast-track relief for small businesses in the wake of Helene failed in the U.S. Senate, however, after Sen. Rand Paul, R-Ky., objected to the unanimous consent motion on the chamber floor. Paul attempted to incorporate an amendment that would have taken money from the U.S. Department of Energy to “pay for” the additional SBA aid.

Tillis called Paul’s amendment “disingenuous” and a “poison pill” — a term used to describe an add-on to a piece of legislation that is certain to cause the bill to fail. He accused Paul of “playing a procedural game.”

“This bill, if it got amended, has no prayer,” Tillis said. “I assume that Sen. Paul knows how to count votes, he has to know that he doesn’t have the votes to get this bill done if it gets amended.”

Warner also pushed back against Paul’s effort. He noted that, since Oct. 15, 34,000 businesses across the U.S. have applied for SBA relief. He pointed to Damascus, where, he said, every business and home was affected by Helene.

“We’ve got communities that, without this relief, are going to die,” Warner said on the floor of the Senate on Nov. 14. “We owe it to the folks in Damascus and Southwest Virginia, in North Carolina, and across all of the jurisdictions in our country that have been hard hit, to do our job.

“This kind of assistance, whether it’s FEMA dollars or SBA loans, is not charity, it is their right as Americans. It’s what we pay our taxes for,” he added.

So, what’s next? The Biden administration submitted a funding request to Congress for a full disaster supplemental bill, which would include money for SBA, among other priorities. If that funding request is passed by Congress, businesses could see relief within a few weeks. Warner and Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Va., are pushing for a vote on the bill this week, in the hope that business owners could begin to receive funds before the end of the year.

“I think it’s very, very sad,” Wilson said of the maneuvering in Congress that halted fast-tracked funding for the SBA. “I don’t understand the problem in funding small businesses to get back on their feet.”

Rep. Morgan Griffith, R-Salem, said he plans to support a supplemental bill to provide the SBA with the funds needed for disaster recovery in the U.S. House of Representatives.

The damage already done

Even if Congress were to pass a bill to fund disaster recovery in early December, both Wright and Wilson fear they won’t be able to make up revenue lost during what was usually their busiest time of year.

“October is such a great month for travel, and I couldn’t open at all in October, so I just closed. I was losing money,” Wilson said.

When he learned that the SBA didn’t have money to support him or his neighbors in the immediate aftermath, he said he went to “Plan B.”

He has started catering on the side through the holidays to help him pay the rent and utilities. He applied for some grants administered by Washington County, and he plans to go to the bank to borrow money to rebuild. Wilson set up a GoFundMe that yielded $30,000, but that hasn’t been enough to keep all of his employees while he waits for the money to rebuild.

“Thirty thousand dollars doesn’t go a whole long way when you’re doing payroll, so I pretty much have spent that money already and anything else is out of my own pocket, but I’m tapped out on funds myself,” he said.

“It’s sort of unbelievable to me that we can’t take care of our own people, but we can send millions and billions of dollars elsewhere. That’s what really sticks in my craw,” he added, regarding the lack of money appropriated by Congress for the SBA.

Warner publicly pushed the Biden administration to include funding for public lands in the disaster relief request sent to Congress, in a post on X. He noted that natural resources like the Creeper Trail are going to need significant funding to be rebuilt. Kaine and Griffith signed on in support of the effort in a letter to the White House on Tuesday.

Without the eastern half of the Creeper Trail, Wright estimated that the town has lost millions of dollars in revenue already this year in the two months that the portion of the trail has been closed.

“October is by far the busiest time of year, and we lost — I can’t even imagine. It’ll make me cry if I think about how much business we lost this year,” he said.

He’s unsure if he’ll ever be able to hire back all 47 of his employees.

The county administration is distributing grants, he said, and he received $5,000 to clean up mud and water damage. But if the community is going to survive the devastation from Helene, it’s going to need more help, though Wright said he’s unsure where else to look for assistance.

Gov. Glenn Youngkin said in mid-November that his office has been discussing the possibility of state aid with the General Assembly, but first, they need to determine how much aid will be provided by the federal government. As of right now, there is no state aid for small businesses affected by Helene.

Wright pointed out the lack of money available through the SBA may make recovery for new businesses or businesses that were already struggling even more difficult.

“Some of us received so much damage that we don’t know if there’s going to be any business to come back,” he said.

Business owners uncertain about loans, future

On Oct. 15, the SBA announced that it had exhausted funds for its disaster loan program. It has paused the distribution of funds until Congress appropriates additional funds, but a spokesperson for the agency said business owners should continue to apply during that pause.

“We’re encouraging people to continuously apply if they have been affected in anticipation of approval of the funds because they will be approved, it’s just a matter of time,” Tim Watson, an SBA spokesperson, said Wednesday.

Since Helene hit the Southeastern U.S., 266 applicants have sought SBA funding in Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina and Tennessee, Watson said.

Wright said it’s the uncertainty about whether Damascus will bounce back that has caused some hesitancy among business owners to seek out loans from SBA.

“It’s going to be tough to borrow $50,000 or $100,000 and pay that interest because we don’t know if the business is coming back, it’s going to be a couple of years before we can recreate the narrative of why people should come here,” he said. “Even if [SBA] had that money, it’d be a gamble to take that interest on when we don’t know what the future holds for us.”

To Wilson, owning a small business in a rural community is a labor of love, but this process has left him feeling defeated.

“I’ve lived through COVID. and I’ve lived through the flood, and it’s almost not even worth it to own a small business, they make it so hard,” he said. “If they had to live through it, maybe they would understand.”