In 2020, the General Assembly passed the Clean Economy Act, which mandated that the state’s power grid become carbon-free within 30 years.

That’s set off a land rush of solar energy projects across the state.

The Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service at the University of Virginia has now put together the Virginia Solar Database, which attempts, for the first time, to figure out just how many solar projects Virginia has — and where.

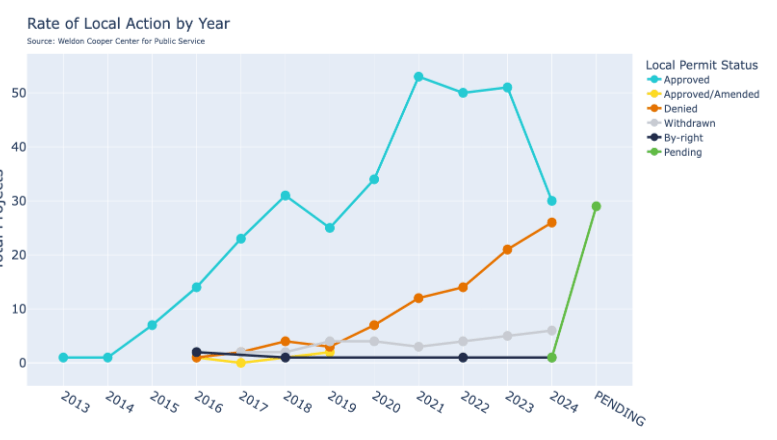

The database currently documents 491 projects across the state, of which 343 have been approved (five of those through by-right zoning).

Very few of those, however, are in the districts of the legislators who voted for the law that has prompted so much solar development.

This is notable because solar development has become increasingly controversial, particularly in Southside Virginia, the hotbed for solar farms.

The database shows the approvals for solar projects are falling and rejections are rising — and while those lines haven’t crossed yet, they’re on trendlines that will.

That’s raised concerns that Virginia may not be able to meet its solar goals if local governments keep rejecting solar permits. In response, there’s been talk of having the state take over the process. The Commission on Electric Utility Regulation recently proposed creating a special board to advise localities on large solar projects, with the proviso that if a local government rejected a project deemed of “statewide significance,” the solar developer could appeal that decision to the courts or the State Corporation Commission. Or, perhaps, the board’s advisory opinions could simply become outright approvals, cutting out local government entirely. (Cardinal’s Matt Busse has written more about this proposal.) As you might imagine, local governments don’t much like this idea because they see it as a case of the state potentially usurping their authority on land-use matters.

Virginia is in a bind here. The state has mandated more solar energy, but many local governments are thwarting those goals.

Some communities seem to be adamantly anti-solar. Culpeper County has approved just one of seven solar proposals. Fauquier County, one of eight solar proposals. Dinwiddie County, one of nine. Meanwhile, Northumberland County has rejected all five proposals. On the opposite end of the spectrum is Pittsylvania County, which the database shows has never rejected a solar proposal.

My expertise is in politics, not energy, so let me state this more plainly: We have a law enacted by Democrats that is being held up by conservative local governments. Or perhaps this: We have a law enacted (mostly) by legislators from the urban crescent who don’t have to deal with any of the opposition to solar from rural residents, many of whom see it as turning their countrysides into an industrial landscape.

This seems an inevitable, and unhealthy, political conflict that pits two different parts of the state against one another.

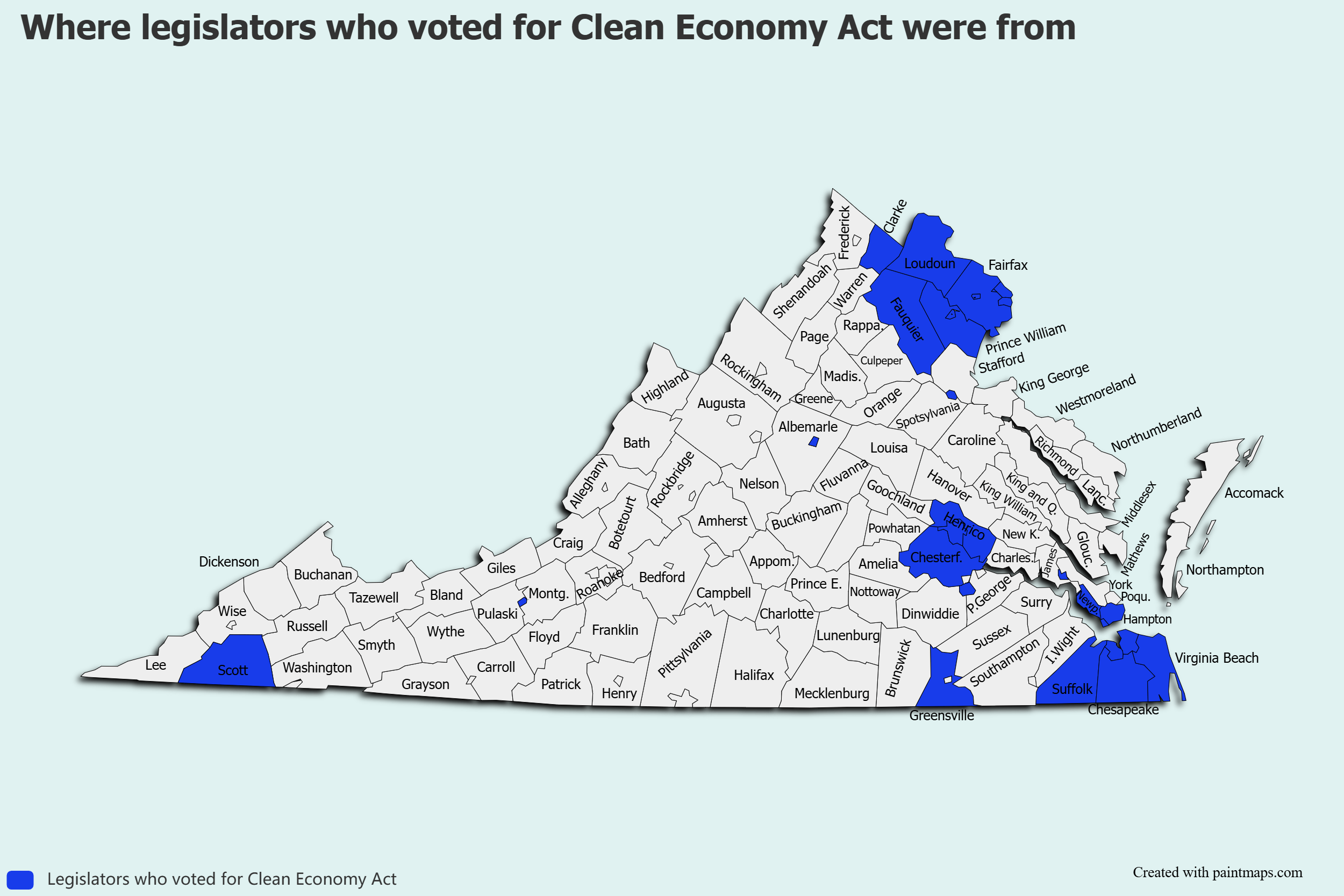

Let’s take a closer look at this divide. This map shows the home cities/counties of the legislators who, in 2020, voted for the Clean Economy Act.

Within those localities, the Virginia Solar Database shows just 29 of the state’s 343-plus solar projects. Only one of those, in Chesterfield County, is in the largest size classification of more than 150 megawatts.

District lines have changed since then, but, in the case of the legislators from Northern Virginia, Richmond and Hampton Roads, their lines are still within the blue areas on the map. In the case of the five pro-Clean Economy Act legislators from outside the urban crescent, three are no longer in the legislature. The remaining two — Sen. Creigh Deeds, D-Charlottesville, and Del. Terry Kilgore, R-Scott County — have much bigger districts, geographically speaking, but even if we look at those districts, and not just their home localities, we still don’t find many solar projects. Deeds’ district has four in Albemarle County, two in Amherst County and possibly one in Louisa County (it’s hard to tell where the district line is), none of the largest size. Kilgore’s district has three in Wise County, only one of the largest size.

Including those ups the number to 39 of the 343 projects, but the political calculus remains the same: The legislators who voted to set off a solar boom don’t have to deal with the political reaction to it. Furthermore, seven of those projects are in just two counties — Clarke and Greensville — whose pro-Clean Economy Act legislators are no longer in the legislature.

Here’s what is in the districts of many of those pro-Clean Economy Act legislators: data centers. It’s data centers that are driving up the demand for power. We’d need the solar anyway to comply with the non-carbon requirements of the law, but now we need more power, period.

This is creating friction that many legislators from the urban crescent may not fully appreciate: Many rural residents in Southside feel that they’re being asked — no, not asked, told — that they have to sacrifice their counties to satisfy the power demands of Northern Virginia. Their anger is very real.

A lot of the opposition to solar is irrational and just plain wrong. I’ve heard all sorts of wild conspiracy theories that I won’t dignify by repeating. However, the most grounded opposition is simply that people in rural areas don’t like how solar looks. A field covered with solar panels doesn’t look like a field to them, no matter how many sheep are grazing there. It looks like a factory, which it sort of is — an energy factory. That may seem a trivial concern to some, but in many rural areas, it strikes at the very heart of what it means to be rural.

To be sure, the rural opposition to solar is not universal. Many farmers like the idea of producing revenue off land that otherwise wasn’t growing a crop. Local governments certainly like the idea of tax revenue. Solar is fascinating politically because it splits both left and right: Some on the left have environmental concerns about the loss of farmland, some on the right champion solar as a property rights issue.

Whatever the politics, the fact remains that the burden here is very unequal: Rural Virginia in general, and Southside Virginia in particular, is being expected to become an energy production center, something none of its legislators voted for.

Loudoun County, the home of Data Center Alley, has only one solar project that shows up in the database — the 835-acre Dulles Solar and Storage.

Prince William County, which is now filling up with data centers, shows up at zero.

So does Fairfax County.

Meanwhile, Halifax County has 17 projects, totaling 5,358 acres. (Solar panels don’t necessarily cover all that acreage, but that’s the total amount of land involved.)

Pittsylvania County has 17 projects, totaling 11,539.96 acres. (For context, that’s about 3.5 times bigger than the Southern Virginia Megasite, the large-scale business park that recently landed its first tenant.)

Charlotte County has nine solar projects, taking up 26,323 acres.

I increasingly hear elected officials and community leaders in Southside grumbling about solar. (Some do more than grumble, but I don’t think I can print those words.) They feel their part of the state is being taken advantage of and not getting a fair deal out of this. They’re giving up their viewsheds for solar, and what are they getting out of it? Yes, I realize we’re all getting a planet that might someday have less carbon in the atmosphere, but that seems a pretty distant concept. From their point of view, Northern Virginia is getting the jobs, while Southside is paying the price. I’m not necessarily embracing every complaint about solar (which I personally like), I’m just reporting what I hear.

I also hear things such as:

- If data centers require so much energy, why can’t they put solar panels on all those flat roofs? (The answer: That’s where the cooling equipment is.)

- Before Southside is expected to produce more energy, why can’t Northern Virginia produce more of its own? (The answer: Good luck with that. Solar takes up land, and you can’t site a nuclear power plant that close to a metro area. And it would take a lot of rooftop solar to equal some of these sites in Southside.)

The amount of energy required for data centers is enormous. The Virginia Mercury recently published an opinion piece with these eye-opening statistics: A single data center recently approved in Caroline County will use as much electricity as a 3,500-acre solar project in Spotsylvania County that is said to be the largest solar project east of the Rockies. (That’s 3,500 acres of panels; the total site is 6,350 acres). Dominion Energy is building a 176-turbine off-shore wind project off the coast of Virginia Beach. That’s enough energy to power … just a single data center in Hanover County. (Disclosure: Dominion is one of our donors, but donors have no say in news decisions; see our policy.) The more data centers we allow, the more we’re going to need energy, and a lot of that is going to be solar energy in rural Virginia, which is becoming increasingly resistant to bearing that burden.

I don’t have a solution to offer here, but legislators who are contemplating any plan to bypass local governments should understand the depth of feeling about solar in rural Virginia. We expect everyone to live under the same laws, but the reality here is that the legislators most interested in seeing, even requiring, more solar won’t have it in their districts.

Why Democrats should listen to more country music

That was the headline of a recent column, where I looked at how, if Democrats listened to more country music, they’d better understand their political disconnect with working-class Americans. Let’s just say it was not universally popular with our Democratic readers. On the other hand, Del. David Reid, D-Loudoun County and a country music fan, responded with an opinion piece about four country songs with surprisingly progressive lyrics. He recently shared some of the feedback he got to his column. That leads me to a recent song by Spencer Hatcher, a country musician from Rockingham County. I’ll talk about that in more detail in Friday’s edition of West of the Capital, our weekly political newsletter.

You can sign up for that or any of our free newsletters below: