The Mountain Valley Pipeline took a decade to build and was challenged all along the way by lawsuits and the occasional protester chained to a bulldozer or camped out in a tree.

Across rural Virginia, opposition to solar energy projects is rising and some legislators are weighing whether they will need to set up a system for the state to override local governments who are resistant to allowing solar farms.

In Southwest Virginia, the mere suggestion that the region might host a small nuclear reactor was enough to set off protests.

In Botetourt County, the wind farm proposed nine years ago still isn’t built, which means Virginia remains one of just 10 states with no on-shore wind farms.

In Pittsylvania County, a proposed battery storage project drew opposition and the developer withdrew the request last month.

In Chesterfield County, a proposed Dominion Energy natural gas plant has drawn opposition from neighbors, environmental and civil rights groups and at least one state legislator. Some still aren’t reconciled to Dominion’s offshore wind farm off the coast of Virginia Beach. Just a few days ago a reader emailed me to complain about being able to see the blinking warning lights at night. (Disclosure: Dominion is one of our donors, but donors have no say in news decisions; see our policy).

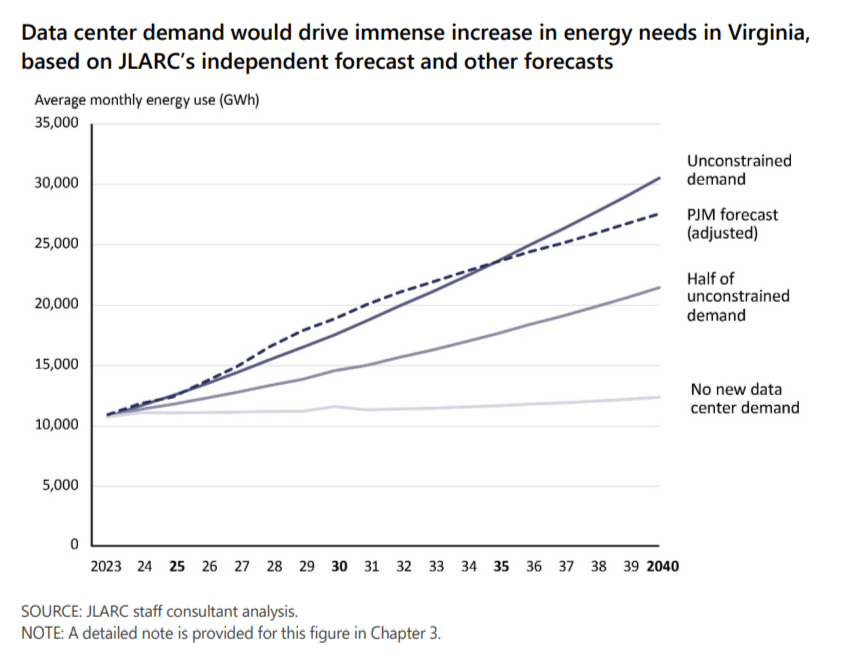

It’s clearly hard to build energy-related projects in Virginia. Whether that’s good or bad may depend on your point of view, but now comes a state report that says that if nothing slows the growth of data centers in Virginia, the demand for electricity will nearly triple by 2040.

That means we’re going to need to build a lot more energy-generating facilities, whatever form they might take. “New solar facilities would have to be added at twice the annual rate they were added in 2024, and the amount of new wind generation needed would exceed the potential capabilities of all offshore wind sites that have so far been secured for future development,” says the report from the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, the General Assembly’s research arm. “Large natural gas plants would also need to be added at an equal or faster rate than the busiest build period for these facilities (2012 to 2018).”

The report called this “very difficult.” It’s difficult to do given the local opposition to any form of energy and is also difficult given the Virginia Clean Economy Act’s mandate that the state’s power grid go carbon-free by 2050. However, the report said that even if the Clean Economy Act went away, even meeting only half this projected demand would still be “difficult,” just not “very difficult.”

“If VCEA requirements were not considered,” the report said, “the biggest challenge would be building new natural gas plants. New gas would need to be added at the rate of about one large 1,500 MW plant every two years for 15 consecutive years, equal to the busiest period of the last decade (2012 to 2018). If it is assumed that VCEA requirements would be met, the biggest challenges would be building enough wind, battery storage, and natural gas peaker plants.”

To quote the great philosopher Waylon Jennings, “Tell me one more time, just so’s I’ll understand.” The only difference is he was asking how to become a country music star; the question here is how are we supposed to generate that much energy when there’s so much opposition to, well, almost anything. (About the only thing that hasn’t generated intense opposition, at least not yet, are the small nuclear reactors that Dominion and Appalachian Power have proposed. Perhaps the reason is that Dominion wants to locate its small modular reactor at its existing North Anna nuclear station in Louisa County, while Appalachian has proposed one for one of its substations in Campbell County that’s near a site where the Lynchburg-based BWX Technologies nuclear company already has nuclear materials.)

It’s not as if we can just do without data centers. Sure, Virginia could say “enough’s enough” and discourage their development, but they’d simply go elsewhere. That might solve our problem, but it would also slow our economy. The same report that outlined the rising power demands also laid out how important data centers are to the state’s economy: 74,000 jobs, $5.5 billion in labor income, $9.1 billion in gross domestic product. In Loudoun County, data centers account for 31% of the tax revenue. In Mecklenburg County, one of the few places outside Northern Virginia with data centers, the revenue from data centers has helped fund a new school.

The concern about the power demands of data centers also comes just as some of them are starting to take a closer look at locating in rural Virginia, a part of the state that very much needs the jobs and tax revenue. Just Tuesday, AVAIO Digital Partners announced plans to build a data center in Appomattox County, a county rocked more than a decade ago by the closing of the Thomasville Furniture plant, which once employed more than 1,200 people. Appomattox is now working through an economic transition and doing pretty well; its population is growing and getting younger, which sets it apart from many rural counties. Those localities would be very unhappy if the data center buffet gets cut off just because the most affluent counties in Virginia have gorged themselves.

I’ve written before that rural areas are unhappy at having to shoulder the energy burden for Northern Virginia and all its data centers. Will that change if they get some of those data centers? Your guess is as good as mine; the reality is that not many people want an energy-generating facility near them, no matter what type of energy it is — be it solar panels turning a previously green field black or wind turbines spinning ’round and ’round or a natural gas plant releasing carbon or a nuclear plant splitting atoms.

An opinion piece in the Virginia Mercury recently asked: “Data centers approved, solar farms rejected: What’s going on in rural Virginia?” The column singled out Hanover County, which approved a data center and turned down a solar project in the same meeting. As someone who lives in rural Virginia (just not a county with either a data center or a solar project), I can answer that: jobs. Rural governments see economic development as a core mission; they don’t have the responsibility of figuring out the energy demands of those decisions. Should they? What would happen if, before a locality approved a data center, it had to also devise a plan to generate the power to run it? Many local governments — particularly small, rural ones — aren’t staffed for that. They say a lawyer in court should never ask a question he or she doesn’t know the answer to, so I may be treading on dangerous ground here as a commentator who sees himself as an advocate for rural Virginia because I don’t know what the impact of such a policy would be. Still, it seems a question worth asking.

The JLARC report’s emphasis on new generating capacity certainly got attention. Del. Josh Thomas, D-Prince William County, released a statement: “During the presentation, commission members were visibly shocked as they learned that a 1,000-megawatt data center campus (like the one in my district) requires more electrical power than the entire output of the Lake Anna nuclear plant.”

However, the report also mentioned something else Virginia will have to do: import more power. With no changes and “unconstrained” data center growth, Virginia will need to double the amount of power it imports — a 100% increase. With data center growth constrained to half its present rate, Virginia energy imports would still need to increase by 50%, the report says. Either way, the report points out that Virginia’s ability to import energy depends on other states building more power generation.

That might seem a way for Virginia to avoid unpleasant choices, but here’s what that JLARC report doesn’t say: A lot of that out-of-state energy produces more carbon than we could produce here with solar, wind or nuclear. Let’s look at some of the other states in the same PJM Interconnection grid as Virginia (PJM is the organization that manages the power grid).

If we import power from West Virginia, then we’re importing power that’s 88% coal-generated, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. If we import it from Kentucky, then it’s 64% coal. If we import it from Pennsylvania, then it’s 63% natural gas. If it comes from Ohio, it’s 59% natural gas.

I see no easy solutions here, only hard choices: Do we slow down a certain form of economic growth, just when it’s starting to benefit the parts of the state that need economic growth most? Do we require rural areas to accept energy facilities they don’t want and which, in the case of solar, is seen by some as changing the rural character of the community? Do we modify the Clean Economy Act to allow more carbon to be pumped into the atmosphere? Do we hold fast to that carbon-free goal but import more energy, which is often carbon-intensive? Or do we unplug from our digital world so that we’re not so dependent on data centers?

I don’t know what the answer to those first four questions will be, but I can guarantee you what the answer to that last one is.

For more on the JLARC report on data centers, see the news story by Cardinal’s Matt Busse.

Get a bonus column every week

I write a weekly political newsletter, West of the Capital, that goes out Friday afternoons. Consider it a bonus column. This week I’ll have more on ranked-choice voting, rural mail delivery and the 2025 legislative elections.

You can sign up for that or any of our other free newsletters: