As Virginia’s deer hunting season drew near early this fall, veteran Bedford County hunter Barry Arrington was preparing as he has for decades.

But unlike hunters who were making final preparations with their gear and hunting stand locations, Arrington did his work at a computer, sharing a message of personal tragedy — and of strength in the face of that tragedy — in hopes it would spare any other hunter from going through what he had.

In the fall of 1994, Arrington fell from a treestand and became paralyzed from the chest down. Within days, still lying in his hospital bed, he was publicly telling his story, the start of decades of being an outspoken tree stand safety advocate and an inspiration for other disabled sportsmen and women.

Arrington died Dec. 14 at Carilion Roanoke Memorial Hospital after a period of declining health in recent years. He was 63.

“He went through hell,” said his younger brother, Andy Arrington. “But he wanted people to see that no matter what you go through, you can survive it.”

The Arringtons operate an orchard in the shadow of Flat Top, one of the two Peaks of Otter. As a young man, Barry Arrington enjoyed playing competitive slow-pitch softball with his buddies and loved chasing whitetails in the fall and wild turkey gobblers in the spring.

The afternoon of Oct. 30, 1994, Arrington headed to a distant corner of the family farm to set up a deer stand in anticipation of early muzzleloader deer season.

Barry Arrington

Barry Lynn Arrington, 63, of Bedford died Dec. 14 at Carilion Roanoke Memorial Hospital. He was born in Tucson, Arizona, on June 16, 1961.

Survivors include his siblings Andrew Arrington, Steven Arrington and his wife, Donna, Bernice Davidson and Brenda Parker; Jeff Witt, a friend who was like a brother; and his most recent caregiver, Laura Stanley. He is also survived by numerous nieces and nephews.

The family urges those wishing to make memorial contributions in Arrington’s memory to consider a donation to the Bedford Outdoors Sportsmen Association or Hunters for the Hungry.

Funeral services are 1 p.m. Thursday at Tharp Funeral Chapel in Bedford. The family will receive friends 4-8 p.m. Wednesday at Tharp Funeral Home & Crematory, Bedford.

“I had used a [safety] belt to put it up, but I had undone my belt to get up in it,” Arrington said in a Roanoke Times story that ran less than three weeks after the accident. “I was checking for some shooting lanes to clear, and I decided to just put my weight on the stand to make sure I had it settled in the tree real good. I didn’t hook my belt back up, I just had my hands around the tree. The next thing I knew, I was on the ground.”

Arrington had severely dislocated his sixth and seventh vertebrae, crushing his spinal cord. He was paralyzed from the chest down. Things could have been even worse.

“Barry never told anyone where he was going,” Andy Arrington said. “But that day he told Dad exactly where he was going to be at the south corner of the farm.”

When Barry Arrington didn’t come home, a search was initiated, and he was quickly located before temperatures dropped to dangerous levels.

“I was at a friend’s but just had a weird feeling I needed to get home,” said Andy Arrington, who arrived as his brother was being prepared for an emergency helicopter ride, first to Roanoke and eventually to the University of Virginia hospital in Charlottesville. “When I saw him and the condition he was in, I almost blacked out.”

Within a couple of weeks, Barry Arrington had invited members of the media to his bedside for interviews.

“His message was, ‘It happened to me, but it doesn’t have to happen to you,’” Andy Arrington said.

Hunting supply stores across Western Virginia quickly sold out of safety belts and harnesses. Statistics maintained by the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (then the Department of Game and Inland Fisheries) showed that treestand fall incidents dropped significantly that season.

After months of rehab, Arrington returned home to a different life. He had some movement in his arms, though he couldn’t move his fingers. He eventually became adept at moving around in his powered wheelchair and learned to drive a specially equipped van.

“After the accident, the only way he could avoid being carsick was if he drove,” Andy Arrington said, laughing. “He sort of scared me. It was fun. You definitely didn’t fall asleep.”

Barry Arrington was an avid gardener who proudly shared pictures of the biggest tomatoes he grew each summer. He used a special utility vehicle to move around the farm, and he continued to hunt.

“He killed more big deer and turkeys than most people who can walk,” said Jeff Witt, a friend of 40 years.

Arrington also channeled his passion for the outdoors into advocacy. He partnered with the Department of Wildlife Resources on a video about treestand safety. He gave talks to classrooms.

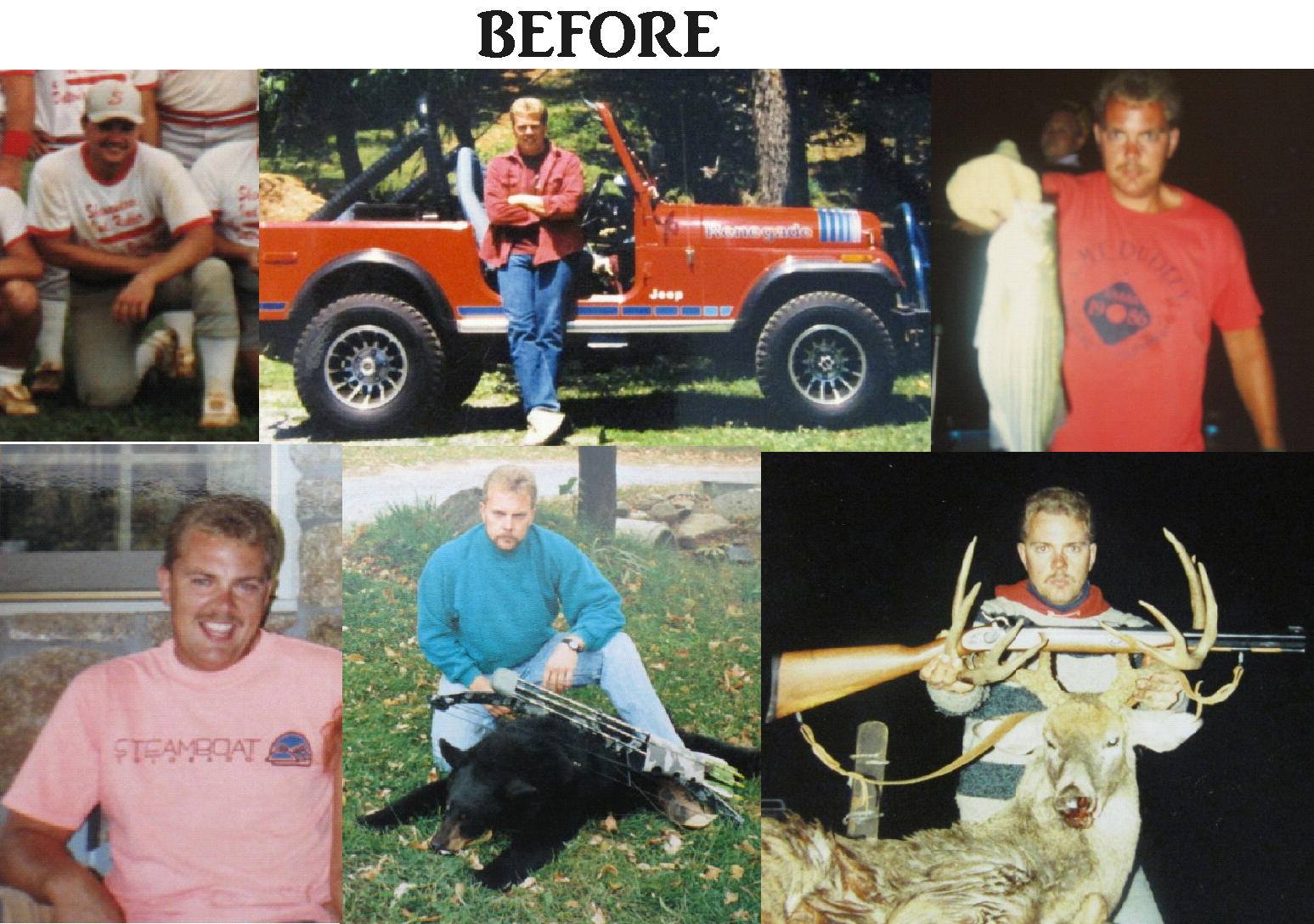

The explosion of Facebook and social media gave Arrington a new and powerful way to reach the state’s hunters, and he annually posted his story — along with many “before” and “after” pictures — prior to fall deer hunting seasons.

“He kept contributing after the accident,” Andy Arrington said. “He didn’t go into isolation.”

His most recent safety post was on Nov. 1

“One last reminder before the VA firearms deer season starts … PLEASE WEAR YOUR SAFETY HARNESS when hunting from a tree stand,” Arrington posted on his Facebook page. “30 years ago on October 30th I made the mistake of not reattaching my safety belt while putting up a stand and it cost me dearly. The fall left me paralyzed from the chest down because of that mistake. The before and after pics below should be enough to convince you to invest in a good safety harness because not being able to walk SUCKS!!!”

The message of treestand safety — which is also an emphasis for hunter education courses — is one Virginia hunters have been getting.

Treestand accidents have declined over the past 25 years. According to statistics compiled by the Department of Wildlife Resources, Virginia averaged 16.8 serious treestand accidents annually from 1994 through 1998. The average was 12.6 for the next five years. The average since 2000 has been 11.7. There have been 23 fatalities since 1998.

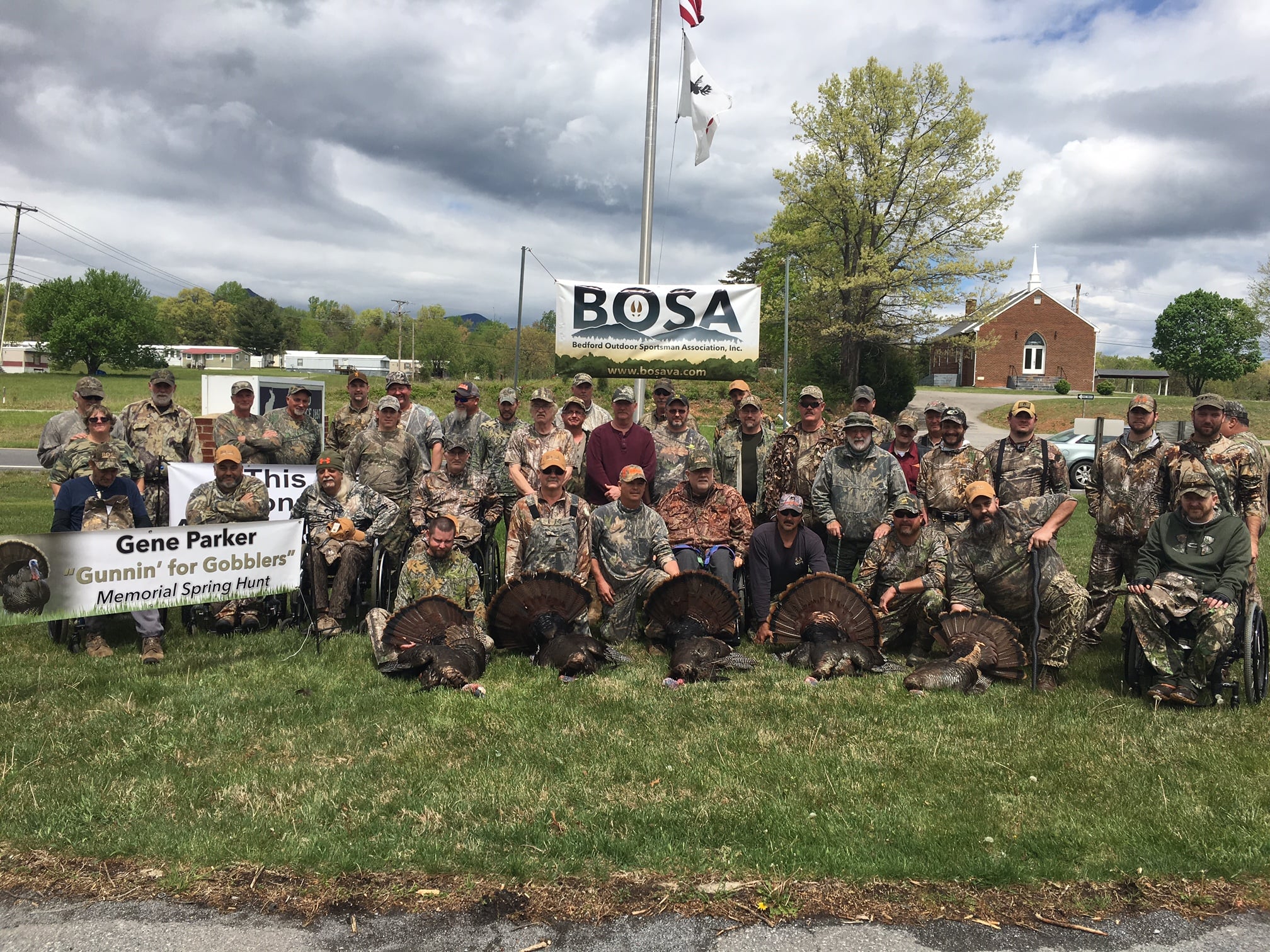

After his accident, Barry Arrington remained active in his Bedford County community and its outdoor recreation culture. He helped establish Arrington’s Orchard as a drop-off location for donations to the Hunters for the Hungry food charity. He served as a guide on events for disabled hunters, including an annual spring turkey hunt first hosted by the Wheelin’ Sportsman organization, and more recently as the Gene Parker Memorial Gunnin’ for Gobblers hunt hosted by Bedford Outdoor Sportsman Association, or BOSA. He was instrumental in expanding the hunt to veterans.

Arrington served as president of BOSA and the James River chapter of the National Wild Turkey Federation.

“He gave people inspiration to try,” Andy Arrington said.

One of those was Cody McCulloch, a Bedford County man who was severely injured in a treestand fall in 2019. Like Arrington, he was hanging a stand and hadn’t yet tethered himself to the tree when the stand gave way.

“I was young, and I felt invincible,” he recalled.

McCulloch’s spinal cord was partially damaged in the fall.

“They told me the best I could hope for was to walk with a gait aid [walker],” he recalled. “I went through those mental struggles.”

Arrington immediately reached out with messages of support.

“He said, ‘I’m not saying it’s going to be easy, but it’s not the end,’” McCulloch said. “He called me a bunch of times. He knew I needed it more than I knew I needed it.”

McCulloch is able to walk with a cane and has numbness in one leg. He knows it could have been much worse.

“I saw what Barry overcame, and I said, ‘If Barry can do it, I can do it,’” McCulloch said. “He could have just sat in his room all day. But he didn’t. He had a drive.”

And a sense of humor.

“One morning we were getting ready to set up in a hunting blind, and I was stumbling around trying to get all of our stuff together,” McCulloch said of a hunting outing with Arrington a few years ago. “He said, ‘What are you doing making all that noise out there?’

“I said, ‘I don’t see you out here!’”

They both laughed hysterically.

Even as Arrington battled bed sores, urinary tract infections and other health challenges that worsened in recent years, he didn’t give up, said his brother. When he was hospitalized in early December, he talked with his brother not about the nearing end, but about future plans.

But Arrington did take time to work with his friend Tracy Travis to pull together decades’ worth of photos for a slide show set to music. Many were grainy photos of a tan, fit and young Arrington posing with trophy deer and turkeys, his beloved Jeep and his softball buddies. But many others were from after the accident, showing Arrington with more game and more friends, many of them also in wheelchairs but active.

“He made her promise to not share it while he was living,” said Andy Arrington, choking back tears. “But we can share it now.”

The soundtrack song of that life captured photos? One Republic’s “I lived.”