The year 2026 marks the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Cardinal News has embarked on a three-year project to tell the little-known stories of Virginia’s role in the march to independence. This project is supported, in part, by a grant from the Virginia American Revolution 250 Commission. Find all our stories from this project on the Cardinal 250 page. You can sign up for our monthly newsletter:

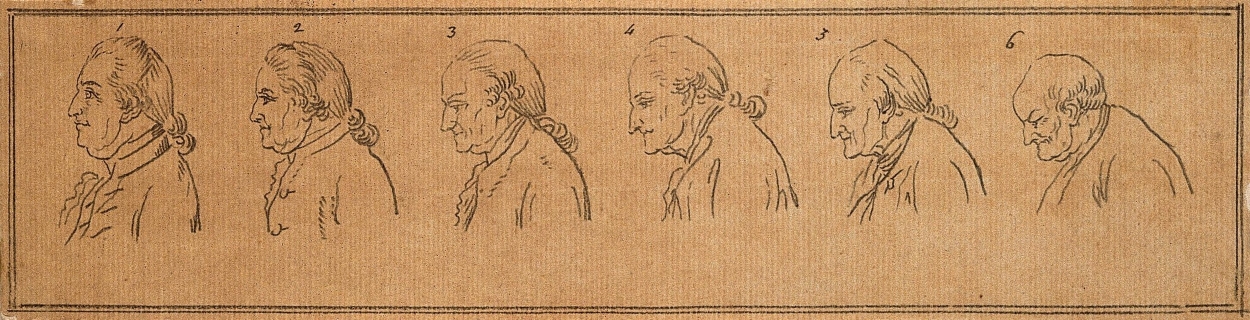

What’s your image of the Founding Fathers? If you picture old men in powdered wigs, you’re not alone.

Rebecca Brannon is a James Madison University professor who studies, among other things, age and the American Revolution. She says her students are often surprised to learn that the leaders of the revolution were actually young or middle-aged. “They would be confused by who in the world let Thomas Jefferson write the Declaration of Independence — he’s just a babe in arms,” she said.

We have a podcast with Brannon about the age of the founders.

Jefferson was 33, Patrick Henry 40, and George Washington 44 on July 4, 1776. Why, then, do we remember them as elder statesmen? It’s because they succeeded. Had they all been hung in 1776, they would be forever frozen in youth and middle age. Instead, many of them lived to become presidents and governors whose powder-whitened heads were preserved in oil portraits. You probably have a picture of Old George in your wallet.

Old men don’t start revolutions. Lenin, Trotsky and Stalin were 47, 38 and 38 in 1917. Marat, Danton and Robespierre were 46, 29 and 31 in 1789.

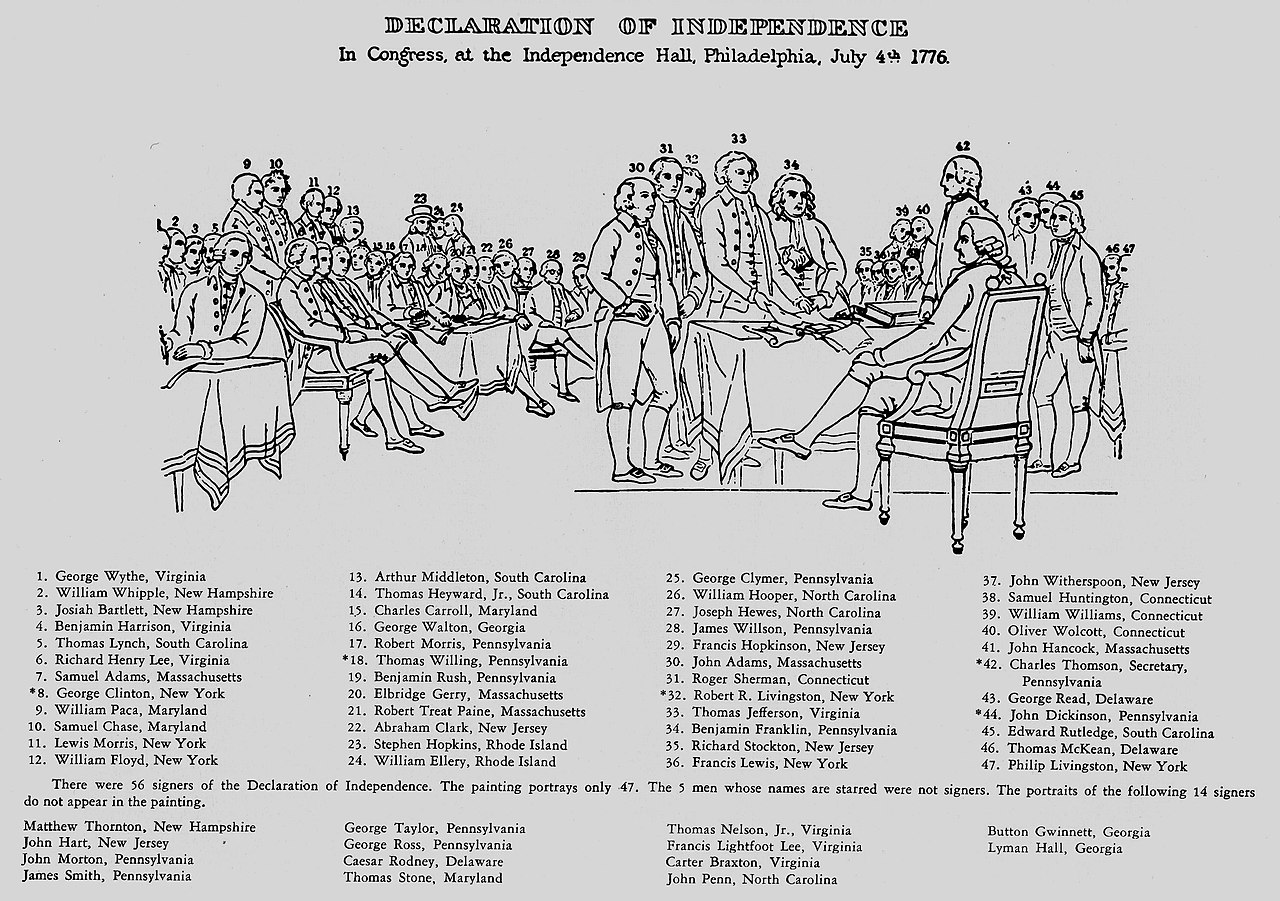

When the Declaration of Independence was adopted in Philadelphia, Virginia’s signers, in addition to Jefferson, were George Wythe, 50; Richard Henry Lee, 44; Benjamin Harrison, 50; Thomas Nelson, Jr., 37; Francis Lightfoot Lee, 41; and Carter Braxton, 39. The five-man drafting committee included, in addition to Jefferson, John Adams, 40; Roger Sherman, 55; Robert Livingston, 29; and Ben Franklin, 70.

With the notable exception of Franklin — courageous and mentally nimble enough to gamble on revolution in his 70s — all were well below the threshold of old age, considered to be 60 in the 18th century, according to Brannon. As far as the powdered wigs, contrary to John Trumbull’s famous painting, it’s doubtful many signers wore them in the summer heat.

In the Revolutionary War, as in all wars, most of the actual fighting was done by the young. James Monroe, an officer in the Continental Army, was 18 in 1776. The Marquis de Lafayette was 18. Aaron Burr, a military hero, was 20. Future Chief Justice John Marshall was 20. Alexander Hamilton, an aide to Washington, was around 20. Nathan Hale, who regretted that he had but one life to lose for his country, was 21. Naval hero John Paul Jones (“I have not yet begun to fight”) was 28. James Lafayette, an African-Virginian who risked execution spying for Lafayette, was about 28 in 1776. Deborah Sampson, who disguised herself as a man and served in the Continental Army from 1782 to 1783, was 15 in 1776.

The concept of a drawn-out adolescence barely existed in the 18th century, especially for poor and working-class families who couldn’t afford to send their sons to college. Young men of 16 could and did join the Continental Army.

While the young were facing musket fire, bayonets and solid shot, it was the middle-aged who steered the course of the great social upheaval.

By middle age, most people have well-formed opinions about “how things might be different, but also what’s worth preserving; how society should work — the ideals that people read about in books — but also how things actually work,” Brannon said.

The middle-aged leaders, who had property and reputations to protect, were “able to command the respect, the adherence and support of a wider percentage of the population, who are more likely to trust that they know how far to go and when to stop. They don’t make an 18-year-old commander-in-chief of the forces.”

But Washington also made sure he had a contingent of younger advisors, like Alexander Hamilton, Brannon said. “They help him keep his finger on the pulse of how to motivate the larger group of enlisteds, and he trusts them to see things in the intelligence reports and the possibilities that maybe his generals wouldn’t see.”

A revolution in aging

In the early part of the 18th century, aging was equated with decay, Brannon said. The aging body was compared to a building falling down or a clock wearing out. “Decay is inevitable, and by extension some kind of disability or inconvenience from your body is inevitable.”

By the revolutionaries’ generation, old age was increasingly seen as “just one more thing that you can control and prevent and push off and ameliorate. And that’s new and revolutionary in its own way, and we’re very much the inheritors of that.

“At the beginning of the 18th century, exercise is something for poor people who can’t avoid it. It’s definitely not something old people should do if they don’t have to. But by the end of the 18th century, everyone should exercise. These elite founders bragged to each other in their letters about how much they’re exercising, because it’s something important to do, and it’s also important for other people to know you’re this strong-willed person who exercises, whether you want to or not, because it’s the right thing, and because it shows you have great self-control.

“Most of them take their exercise on horseback and walking — kind of 18th-century cardio — but Benjamin Franklin takes it further, and believes you need to lift weights as well, and he has all these exercises he does with a kettle bell.

“In a way, they are the first generation to be concerned about how to grow old like we are. Like, ‘How do I head off physical disability? How do I ensure that I not only live a long life, but make that long life as healthy as possible? Today we would call it ‘health-span.'”

The Revolutionary era extended into the early republic, as the Founding Fathers put their stamp on the emerging nation. Of the first five presidents, all were in their 50s except John Adams (61). A man in his 50s was believed to offer “a good combination of health and vigor, and experience and wisdom earned through time,” Brannon said.

The last men of the Revolution

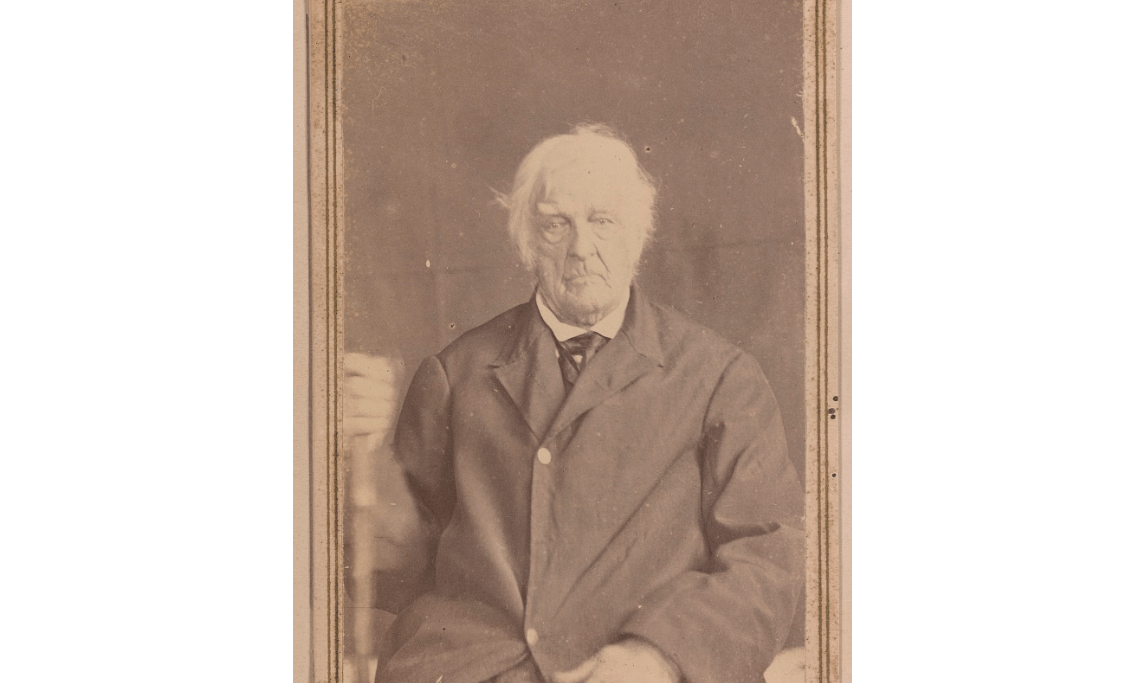

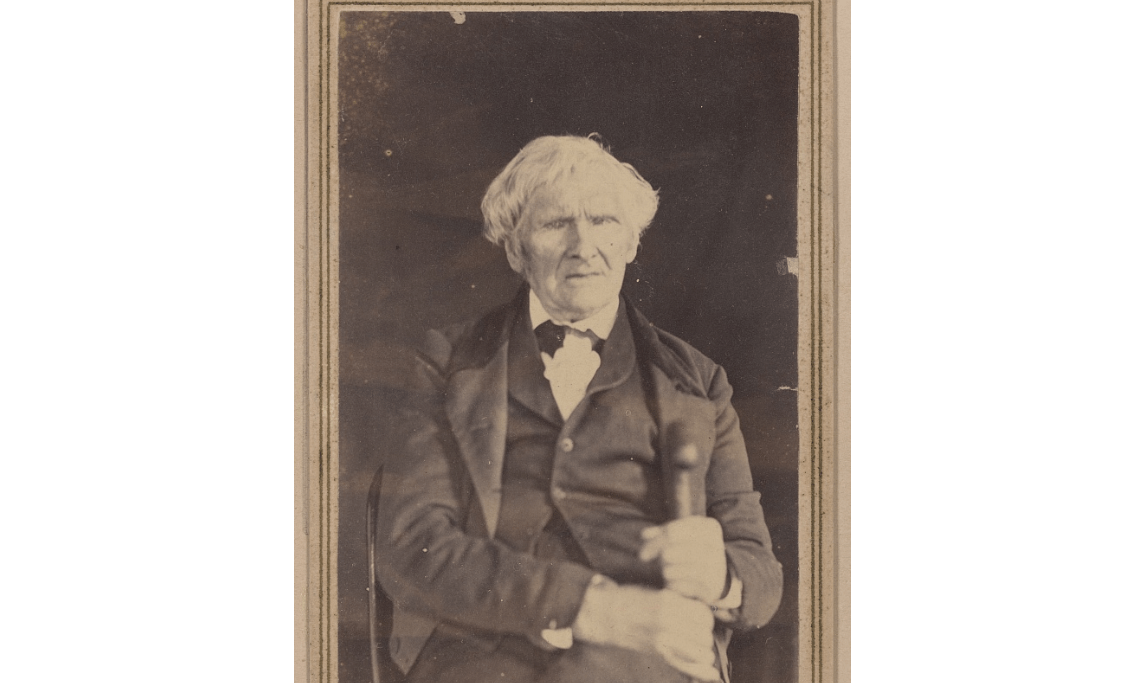

A few veterans — youths during their service — survived into the infancy of photography, providing a visual link to the Revolutionary era. These veterans — their once supple and smooth faces coarsened and wrinkled by time — seem more real, more accessible to us than those who left only a painted portrait, or no picture at all. We may not be able to see Washington directly, but we stand slightly nearer to him by looking into the eyes of soldiers who once gazed upon his face.