The year 2026 marks the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Cardinal News has embarked on a three-year project to tell the little-known stories of Virginia’s role in the march to independence. As part of this, I will be writing monthly columns about the politics of the era, written the same way I’d write them today. The events described here took place in 1775.

Winter has settled on Virginia, and so far it has been an uneventful one with scarcely a hint of snow. The Fairfax County planter, military man and member of the House of Burgesses George Washington records that the new year’s weather has begun “calm, clear, warm, & exceeding pleasant.”

The same cannot be said for our politics. This opening month of 1775 feels much like the proverbial calm before the storm. Or, perhaps more accurately, the calm between storms. We are now starting to see the impact of two big actions from 1774 — Lord Dunmore’s War against the native tribes and the declaration of an economic boycott against Great Britain by the new-fangled Continental Congress. Both have had unintended consequences that are further alienating Colonists from our overlords across the ocean.

Let’s deal with these each in turn.

Virginians won Lord Dunmore’s War — but not the western lands they crave

I write these words from my cabin here in the Blue Ridge Mountains, which not so long ago was the frontier but is no longer. Let’s state a fundamental truth that politicians in London do not seem to understand: Virginia does not end at Williamsburg, or even the Blue Ridge. Virginians conceive of a Virginia that extends far beyond the mountains. When Augusta County was cleaved off from Orange County in 1738, the enabling legislation described a county that extends “to the utmost limits of Virginia.” That would be the Mississippi River; beyond that are lands claimed by Spain. When the French, coming down from Quebec, tried to encroach on those western lands, we fought a war — the French and Indian War — and prevailed. However, what did our British monarch immediately do? He issued the Proclamation of 1763 that forbade settlement west of a line through the mountains. Instead of being blocked by the French and native tribes, we are now blocked by the British and native tribes.

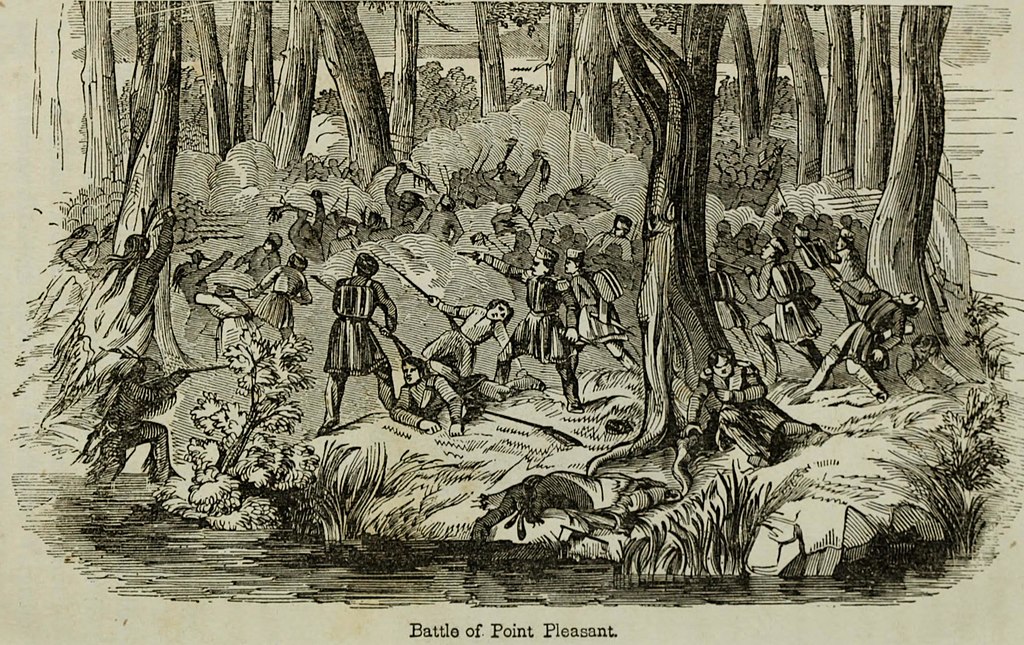

Virginians, under the command of our royal governor (although it was our own Andrew Lewis who was in charge of the actual fighting), dispatched those native tribes at the Battle of Point Pleasant along the Ohio River in October 1774. However, the British still insist those lands west of the Ohio belong not to Virginia (or any of the other Colonies that have conflicting claims) but to French-speaking Quebec, which is firmly under the crown’s control. Virginians are still being deprived of the western lands that they have fought for.

Those men who fought in Lord Dunmore’s War are now returning home, and they’re in a fighting mood about this and many other transgressions by Parliament. Some gathered at Fort Gower, along the Ohio, and adopted a resolution declaring their willingness to fight for their liberties. We understand now that a group of prominent worthies in Fincastle County, that great new county that runs from the New River to the Mississippi, are meeting this week to adopt their own resolution. Given the slowness of communication, we have not yet heard the disposition of this gathering, but, given the men involved, we expect that meeting to issue a resolution that is equally strong in its assertion of rights. (Modern editor’s note: See accompanying story on The Fincastle Resolutions).

The economic boycott of Britain is enriching tobacco farmers — and solving our debt problem

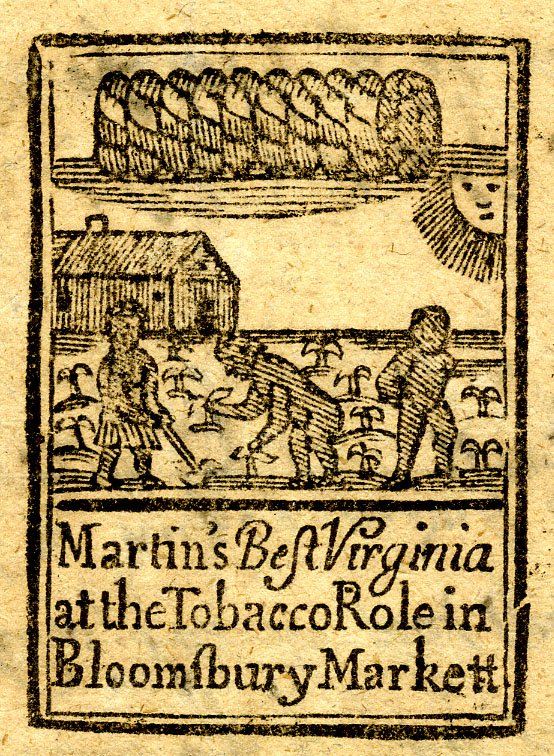

The dirty little secret of Virginia is that many of us are deep in debt to British merchants. There are many reasons for this — the lack of a domestic manufacturing base to supply certain needs is one of them; so is our dependence on the boom-and-bust cycle of two commodities, tobacco and land. Whatever the reasons, the fact remains: We’re in debt, and our British creditors (or their Virginia representative) want to be paid. This has led to social turmoil — and sometimes violence.

In July 1773, the courthouse in Dinwiddie County burned; that’s widely believed to be a case of arson by debtors who felt the simplest way to avoid their court cases was to burn down the courthouse.

The next year saw an even more shocking act of violence. You may (or may not) have heard of the case of Jacob Hite, said to be one of the wealthiest men in Berkeley County. (Modern-day editor’s note: Berkeley County is now in West Virginia, just north of Frederick County.) Hite had both of his main sources of income dry up at the same time: A land deal he had counted on fell through and tobacco prices crashed because of oversupply in the market. That left Hite with no way to pay his debts to a Scottish merchant in Fredericksburg. That merchant, feeling squeezed by his suppliers in Britain, sued and won. The sheriff of Berkeley County seized 15 of Hite’s enslaved laborers and 21 horses. He locked up the slaves in the jail, and the horses in a stable, and announced an auction in the spring of 1774.

Fearing ruination, Hite rounded up an armed band of men who stormed the jail and freed the slaves. When the sheriff organized his own armed band of men, Hite did the unthinkable: He handed out weapons to his slaves and set off down the Great Wagon Road (modern editor’s note: Roughly today’s U.S. 11) for the Carolinas. Hite and most of his armed slaves (some were captured along the way and eventually auctioned off) got away. That’s how desperate some men of property in Virginia are: They’re now willing to arm their slaves if that helps them avoid debt collectors.

While the Hite case was an extreme one, there are other reports across Virginia of debtors “frequently” breaking out of jail, which suggests that these are organized efforts going on to set them free. In Bedford County, merchant John Hook has said he’s found it “very necessary to travel with pistols” because his attempts to collect bad debt had apparently made him a pariah in his county.

Last summer, Virginia’s courts closed. That ostensibly was a protest against Parliament’s response to the tea-dumping in Boston Harbor but had the happy effect of meaning creditors had no way to force Virginians to pay their debts. Then the newly empaneled Continental Congress ordered a halt to exports to Britain, hoping that would pressure British merchants to, in turn, put pressure on Parliament to relax its crackdown on the Colonies. At first, that measure seemed mostly symbolic, because it allowed tobacco exports to continue for a year beyond most other goods. Given that much of our economy revolves around tobacco, that’s a mighty big loophole.

However, something unexpected has happened: The one-year exemption on tobacco has proved to be a godsend. British merchants, fearing they’ll be cut off from their supplies, are now paying record prices for the golden leaf. Prices have nearly doubled. When tobacco prices had dropped, many farmers simply refused to sell their crops at that price and kept them in the barn. Unlike other crops, tobacco doesn’t spoil. Now, with prices shooting up, those hoarders are flooding the market — but instead of prices going down with the glut, they keep going up. The result: Money is pouring into Virginia. That’s enabling many farmers to pay down their debts, or eliminate them entirely. For the first time in a long time, many Virginians are now economically independent of Britain.

Might that start to tempt some minds into thinking about political independence, as well? Not yet, at least not here in Virginia (unlike those hotheads up in Boston). Last fall, Washington wrote to one of his former officers: “I was involuntarily lead into a short discussion of this subject by your remarks on the conduct of the Boston people; & your opinion of their wishes to set up for independency. I am well satisfyed, as I can be of my existence, that no such thing is desired by any thinking man in all North America; on the contrary, that it is the ardent wish of the warmest advocates for liberty, that peace & tranquility, upon Constitutional grounds, may be restored, & the horrors of civil discord prevented.”

However, something else has happened that may be politically significant:

The political interests of small farmers and the gentry now coincide

The western lands issue has united Virginians for a long time. Many of our most prominent politicians — Washington, Patrick Henry, Thomas Jefferson, George Mason — have invested in those lands which they have been unable to claim. Poorer men would like those lands. The two might disagree on the price, but they all agree those lands should be available for sale and settlement — and that the main thing preventing that is the British government.

Now the same thing is happening with the export ban. Anyone who has grown tobacco, be they big or small, is now benefiting from the high prices. By some accounts, two-thirds of the debt owed to British merchants has now been eliminated.

As we look toward spring, many tobacco farmers are now talking about planting other crops — which will further reduce the tobacco harvest, and presumably, drive tobacco prices even higher. Will this bring back harmony with London? Or further exacerbate tensions?

The old year of 1774 was a turbulent one in our relations; we can only guess what 1775 will bring.

Sources consulted: “Forced Founders: Indians, Debtors, Slaves & The Making of the American Revolution in Virginia,” by Woody Holton; Nancy Sorrel’s history of Augusta County published on the county website, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission.

Other dispatches

Dispatch from 1774: Virginia soldiers become the first to declare they’re willing to fight for liberty

Dispatch from 1774: Colonies convene a Congress, vote to boycott British goods

Dispatch from 1774: Settlers massacre Mingo near Ohio River, prompt ‘Lord Dunmore’s War’

Dispatch from 1774: Britain gives Virginia’s western lands to Quebec

Dispatch from 1774: More than 30 Virginia counties pass resolutions to protest British response to Boston tea-dumping

Dispatch from 1773: Smuggling in Rhode Island prompts Virginia to do something revolutionary

Dispatch from 1772: Britain vetoes Virginia’s vote to abolish transatlantic slave trade.

Dispatch from 1769: Governor dissolves House of Burgesses; Virginia vows boycott of British goods

Dispatch from 1766: A sensational murder at Mosby’s Tavern highlights how much Virginia’s gentry is in debt to Britain.

Dispatch from 1766: In Tappahannock, the Stamp Act prompts threats of violence.

Dispatch from 1765: Stamp Act protest prompts House speaker to accuse new legislator Patrick Henry of treason.

Dispatch from 1765: Augusta County mob murders Cherokees, defies royal authority.

Dispatch from 1763: Despite cries of ‘treason!,’ Hanover County jury delivers rebuke to the church — and the crown. (The court case that made Patrick Henry a celebrity.)

Dispatch from 1763: King’s proclamation has united often opposing factions in Virginia (Opposition to the king’s proclamation forbidding western settlement.)

Don’t miss another installment of our Cardinal 250 project. Sign up for our monthly newsletter: