The year 2026 marks the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Cardinal News has embarked on a three-year project to tell the little-known stories of Virginia’s role in the march to independence. This project is supported, in part, by a grant from the Virginia American Revolution 250 Commission. Find all our stories from this project on the Cardinal 250 page. You can sign up for our monthly newsletter:

The Fincastle Resolutions helped pave the way for the Declaration of Independence.

The signers pledged their lives for freedom — and one gave his.

The first thing to know about the Fincastle Resolutions is that they had nothing to do with Fincastle, the town in Botetourt County.

The second thing is that they weren’t technically resolutions.

The third thing is they probably weren’t adopted at the Wythe County lead mines, contrary to a historic marker.

The fourth thing is that the 15 “signers” may not have actually signed it.

The fifth thing is that the original copy is lost.

With so many question marks around it, what positive knowledge do we have about this revolutionary proclamation, adopted 250 years ago this month?

The authoritative study of the Fincastle Resolutions was published in 2010 by Jim Glanville, a Virginia Tech chemistry professor who, after putting away his test tubes and beakers, embarked on a second career as a historian. Glanville died in 2019.

The Fincastle Resolutions were adopted in present-day Wythe County on Jan. 20, 1775, by a 15-man committee of frontier leaders from what was then Fincastle County. They met in response to a call on May 31, 1774, from an “association” of Burgesses meeting extralegally, for local leaders to collect the “sense of their respective Counties.” The Fincastle meeting was given extra urgency by a further call in October 1774, from the First Continental Congress, for the formation of county committees to carry out the recommendations of Congress. The men of Fincastle County, as well as those of Augusta, Botetourt and Pittsylvania counties, were late responding because many had been fighting Native Americans in Lord Dunmore’s War, which ended in the fall of 1774.

The Fincastle statement was addressed to Virginia delegates who attended the Continental Congress in Philadelphia — Peyton Randolph, Richard Henry Lee, George Washington, Patrick Henry, Richard Bland, Benjamin Harrison and Edmund Pendleton. The writers apologize for their lateness, assert their “love” for King George III, and lament the “barbarities and depredations” they have suffered at the hands of “nations of savages.” They allude to the “unlimited and unconstitutional power” of the “venal British parliament,” which attempted “to strip us of that liberty and property with which God, nature, and the rights of humanity, have vested us.”

Fincastle Resolutions committee members

- Arthur Campbell

- William Campbell

- William Christian

- Walter Crockett

- Charles Cummings

- William Edmondson

- William Ingles

- Thomas Madison

- James McGavock

- John Montgomery

- William Preston

- William Russell

- Evan Shelby

- Daniel Smith

- Stephen Trigg

Specifically, they invoke the “civil and religious rights and liberties of British subjects, as settled at the glorious Revolution.” The Glorious Revolution (1688) deposed James II, replaced him with William and Mary as monarchs of England, Scotland and Ireland, and confirmed Parliament as the ruling power in the kingdom. Parliament, in the view of the Fincastle men, had failed disastrously in its duty to protect their liberties.

The political history of Great Britain can be seen as a process by which the monarch gradually lost power and the people gradually gained it, with the Magna Carta (1215) and Glorious Revolution as important steps on the way. George III was closer to a figurehead than an autocrat. “Parliament was already writing the speeches he gave Parliament, and the real head of the government was the prime minister, a term they’d already been using for decades before 1776,” historian Woody Holton said.

In the strongly worded conclusion, they assert their right to the “inestimable privileges” they are entitled to as British subjects and declare that they are “deliberately and resolutely determined never to surrender them to any power upon earth, but at the expense of our lives.” In these sentiments, they pledged to “live and die.”

In putting their lives on the line, the Fincastle frontiersmen upped the ante in the escalating confrontation with the mother country that would climax on July 4, 1776, in Philadelphia.

Richard Osborn published a study of Fincastle signer William Preston in “Journal of Backcountry Studies.”

“A majority of those signing the resolutions who came from a Scotch-Irish background were reminded of their roots in Ireland and their earlier ancestry in Scotland where they felt the English had abused their liberties,” Osborn wrote.

The policies that vexed them most had to do with land. Nothing was more important to Scotch-Irish frontiersmen, many of whom had come to the New World in search of it.

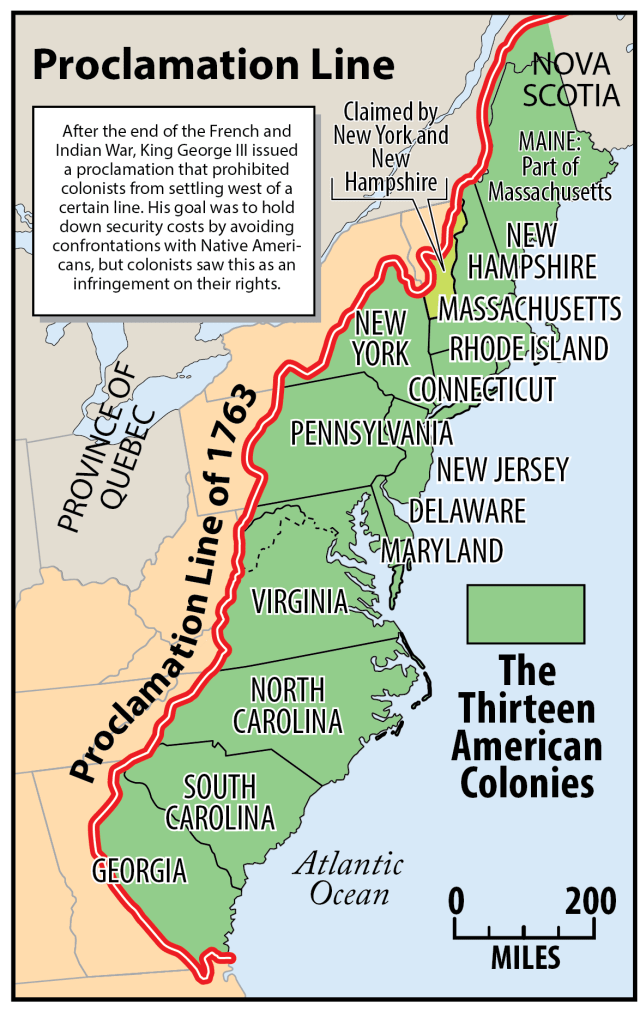

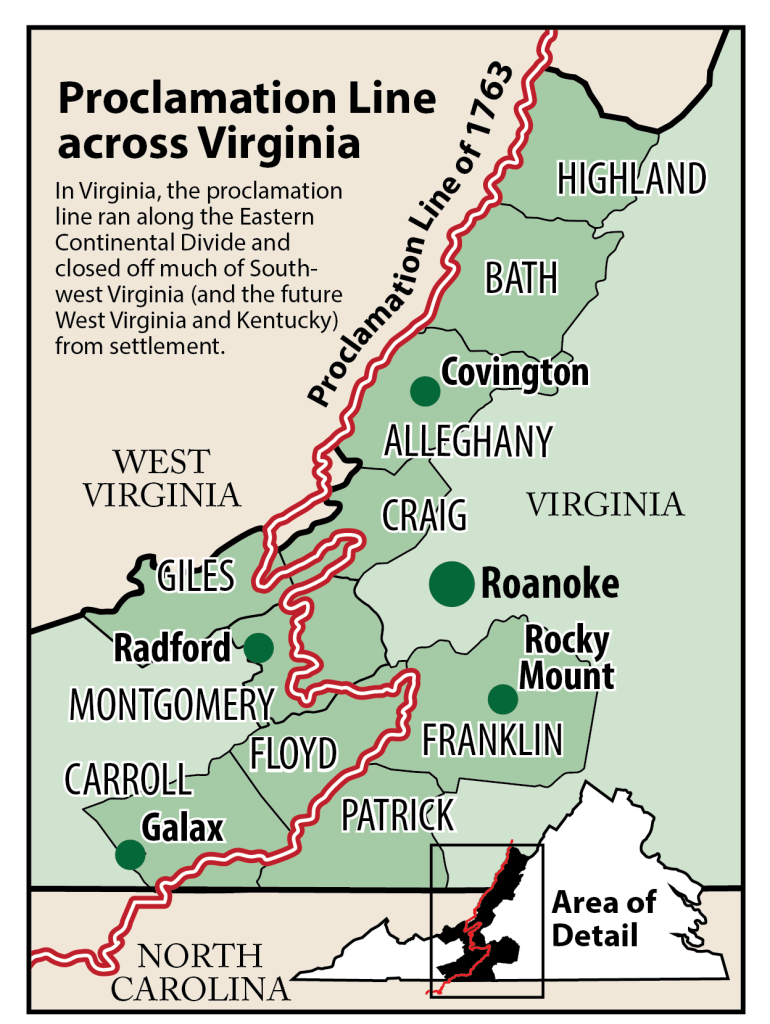

The royal Proclamation of 1763 had set aside land west of the Eastern Continental Divide for the Native Americans, but enforcement had been sketchy. But by 1774, Lord Dunmore began to enforce the Proclamation “even against Seven Years’ War veteran officers who’d obtained a partial exception,” Holton said. Furthermore, the Quebec Act gave all the land northwest of the Ohio River to Quebec.

(See our previous Cardinal 250 stories on the Proclamation of 1763 and the Quebec Act).

Forty Virginia jurisdictions held meetings in the summer of 1774 in response to the Burgesses’ call. By the winter of 1774-75, with the Continental Congress adding its summons, 19 more counties had responded, including Fincastle, Augusta, Botetourt and Pittsylvania. These four counties “produced by far the most important documents of the second wave of committee actions,” Glanville wrote. “The men of all four counties resolved that they would give their lives for American independence.”

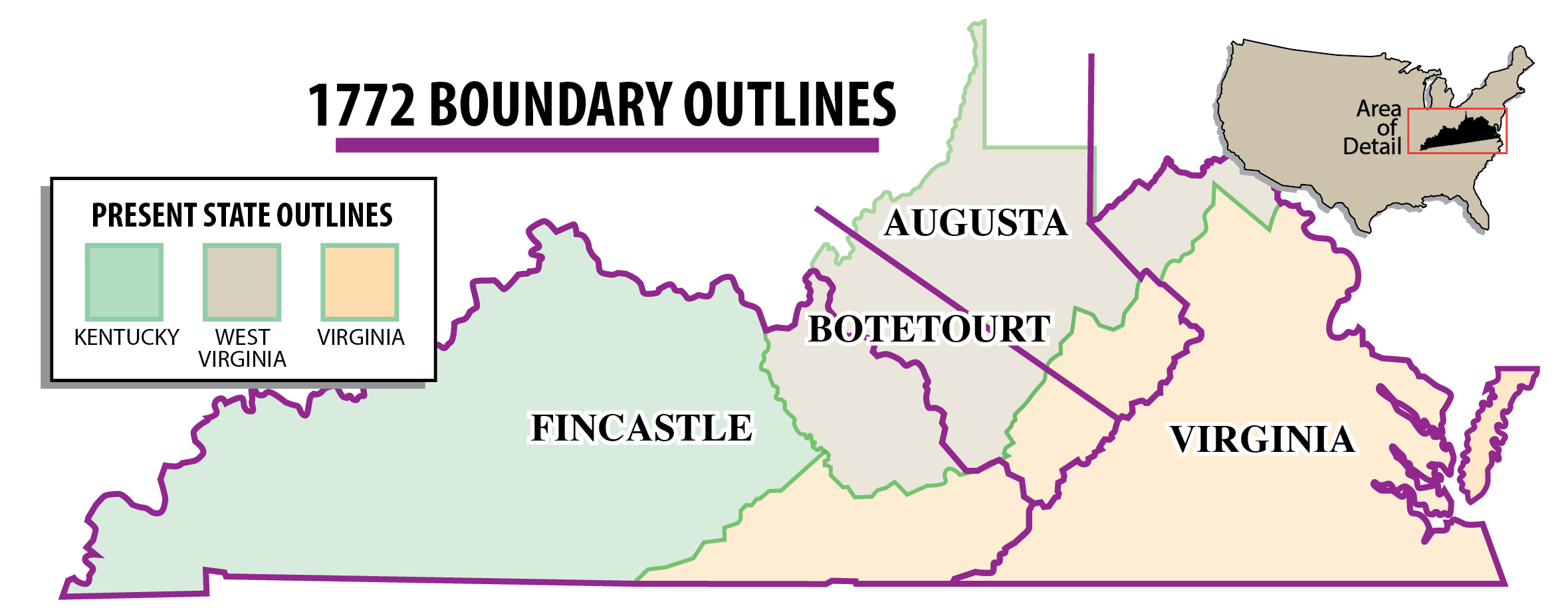

In Virginia history, Fincastle was a gigantic, short-lived county that existed from 1772 to 1776, encompassing western Virginia, part of southern West Virginia, and all of Kentucky — land claimed by native inhabitants who were ready to defend it.

The Fincastle men wanted that land. The fight for it was brutal with atrocities on both sides. Fincastle signer William Russell’s son Henry was tortured to death near Wallens Ridge in modern-day Wise County in 1773.

Experiences like this are reflected in the wording of a recruiting circular published by signer William Preston in 1774 calling for volunteers for a savage assault against the Native Americans: “This useless People may now at last be Obliged to abandon their Country[;] Their Towns may be plundered & Burned, Their Cornfields Distroyed: & they Distressed in such a manner as will prevent them from giving us any future Trouble…”

While the Fincastle committee members can certainly be called frontiersmen, they were far from uncouth. They were well-educated, well-spoken, well-dressed men of good standing in society, according to Michael Gillman, manager of historic sites and Homestead Museum operations for Wytheville.

“As a group,” Glanville wrote, “the signers formed the political core of the region, and they served Fincastle and its predecessor and derivative counties as justices, sheriffs, delegates, elected officials, militia officers, clerks, treasurers, surveyors, and in other public positions of authority.” Four of them had family connections to Patrick Henry.

In January 1775, they gathered in present-day Wythe County, either at McGavock’s Tavern in Fort Chiswell or at the courthouse near the lead mines in southern Wythe.

On Austinville Road near the former site of the lead mines is a marker stating: “HERE ON JANUARY 20, 1775, THE COMMITTEE OF SAFETY OF FINCASTLE COUNTY ADOPTED RESOLUTIONS BOLDLY DECLARING THEIR DETERMINATION NEVER TO SURRENDER THE RIGHTS AND PRIVILEGES GRANTED TO THEM AS VIRGINIANS…”

“There is in point of fact not one documentary record of the committee ever meeting at the Lead Mines, despite hundreds of later statements to that effect,” Glanville wrote.

Gillman said: “You have men coming from modern day Pulaski, Montgomery County … Russell, Washington and Smyth County, and McGavock’s Tavern is situated on the Great Road [modern U.S. 11] at a meeting point, so why would they travel eight miles more south to the courthouse when they could just meet at McGavock’s Tavern and hold their meeting?”

Glanville, a scholar and stickler for accuracy, also disputed the term “resolutions.”

“As published, the record of the Fincastle committee is in the form of an address to Virginia’s representatives to the Continental Congress.” They never say “be it resolved that…” And while the committee members are often called “signers,” there is no proof that the Fincastle resolutions were ever actually signed.

The actual authorship is yet another question. “Many writers have indulged themselves in speculating about who wrote the Fincastle Resolutions, but the fact is we do not know,” Glanville wrote. “They likely were not the work of a single individual. Their significance is that they reveal the collective view of many men on the frontier at an important moment in American history. “

The original copy was lost. The Fincastle Resolutions are known to history from publication in Purdie’s Virginia Gazette in Williamsburg on Feb. 10, 1775.

Several signers were directly involved in the shooting war that followed.

William Campbell commanded a Patriot militia unit, the Overmountain Men, at the decisive Battle of Kings Mountain (South Carolina) on Oct. 7, 1780. The Patriots faced a Loyalist army under a British officer — Americans fighting Americans in a civil war. One Loyalist described the Patriots as “tall, raw-boned, sinewy with long matted hair.” According to legend, Campbell told his Overmountain Men to “shout like Hell and fight like devils.”

“William Campbell’s military role at the Battle of Kings Mountain immortalized him, and it is at least arguable that without that victory the Revolution would have failed,” Glanville wrote. Another signer, William Edmonson, also fought at Kings Mountain.

(See our previous Cardinal 250 stories on William Campbell and the Overmountain Men, including this podcast).

Stephen Trigg paid for his boldness with his life. A Virginia native, Trigg was a merchant, justice of the peace and militia captain. He was about 33 when he served on the Fincastle committee. Later he moved to Kentucky, where he was a militia officer.

The capitulation of Cornwallis in 1781 wasn’t the end of hostilities. In August 1782, a British-Native American force invaded Kentucky. In one of the last actions of the Revolutionary War, they overwhelmed a Patriot unit at the Battle of Blue Licks. The body of Stephen Trigg was later found hacked into pieces.

Full text of Fincastle Resolutions

In obedience to the resolves of the Continental Congress, a meeting of the freeholders of this county was held this day, who, after approving of the association framed by that august body in behalf of all the colonies, and subscribing thereto, proceeded to the election of a committee, to see the same carried punctually into execution, when the following Gentlemen were nominated: Reverend Charles Cummings, Colonel William Preston, Colonel William Christian, Captain Stephen Trigg, Major Arthur Campbell, Major William Inglis, Captain Walter Crockett, Captain John Montgomery, Captain James McGavock, Captain William Campbell, Captain Thomas Madison, Captain Daniel Smith, Captain William Russell, Captain Evan Shelby and Lieutenant William Edmondson. After the election the committee made choice of Colonel WILLIAM CHRISTIAN for their chairman, and appointed Mr. David Campbell to be clerk. The following address was then unanimously agreed to by the people of the county, and is as follows.

To the Honorable Peyton Randolph, Esq; Richard Henry Lee, George Washington, Patrick Henry, junior, Richard Bland, Benjamin Harrison, and Edmund Pendleton, Esquires, the Delegates from this colony who at-tended the Continental Congress held at Philadelphia: Gentlemen, Had it not been for our remote situation, and the Indian war which we were lately engaged in, to chastise those cruel and savage people for the many murders and depredations they have committed against us (now happily terminated, under the auspices of our present worthy Governour, his Excellency the Right Honourable the Earl of Dunmore) we should before this time have made known to you our thankfulness for the very important services you have rendered to your country, in conjunction with the worthy Delegates from the other provinces. Your noble efforts for reconciling the Mother Country and the Colonies, on rational and constitutional principles, and your pacifick, steady, and uniform conduct in that arduous work, entitle you to the esteem of all British America, and will immortalize you in the annals of your country. We heartily concur in your resolutions, and shall, in every instance, strictly and invariably adhere thereto.

We assure you, Gentlemen, and all our countrymen, that we are a people whose hearts overflow with love and duty to our lawful sovereign George III, whose illustrious house, for several successive reigns, have been the guardians of the civil and religious rights and liberties of British sub-jects, as settled at the glorious Revolution; that we are willing to risk our lives in the service of his Majesty, for the support of the Protestant religion, and the rights and liberties of his subjects, as they have been established by the compact, law, and ancient charters.

We are heartily grieved at the differences which now subsist between the parent state and the colonies, and most ardently wish to see harmony restored, on an equitable basis, and by the most lenient measures that can be devised by the heart of man.

Many of us, and our forefathers, left our native land, considering it as a kingdom subjected to inordinate power, and greatly abridged of its liberties. We crossed the Atlantick, and explored this then uncultivated wilderness, bordering on many nations of savages, and surrounded by mountains almost inaccessible to any but those very savages, who have incessantly been committing barbarities and depredations on us since our first seating the country. These fatigue and dangers we patiently encountered, supported by the pleasing hope of enjoying those rights and liberties which had been granted to Virginians and were denied us in our native country, and of transmitting them inviolate to our posterity. But even to these remote regions the hand of unlimited and unconstitutional power hath pursued us, to strip us of that liberty and property with which God, nature, and the rights of humanity, have vested us. We are ready and willing to contribute all in our power for the support of his Majesty’s government, if applied to constitutionally, and when the grants are made by our own representatives; but cannot think of submitting our liberty or property to the power of a venal British parliament, or to the will of a corrupt Ministry.

We by no means desire to shake off our duty or allegiance to our lawful sovereign, but on the contrary shall ever glory in being loyal subjects of a Protestant prince, descended from such illustrious progenitors, so long as we can enjoy the free exercise of our religion, as Protestants, and our liberties and properties, as British subjects.

But if no pacifick measures shall be proposed or adopted by Great Britain, and our enemies will attempt to dragoon us out of these inestimable privileges which we are entitled to as subjects, and to reduce us to a state of slavery, we declare, that we are deliberately and resolutely determined never to surrender them to any power upon earth, but at the expense of our lives.

These are our real, though unpolished sentiments, of liberty and loyalty, and in them we are resolved to live and die.

We are, Gentlemen, with the most perfect esteem and regard, your most obedient servant.