Want more news about Virginia’s demographic trends? We’ve collected all our demographic coverage in one place.

Fairfax County continues to lose population, although its out-migration has slowed dramatically.

Virginia Beach also continues to lose population, as its out-migration shows no signs of slowing. That city now is losing more people than any other locality in the state.

Danville, by contrast, is seeing its population grow for the first time in more than three decades.

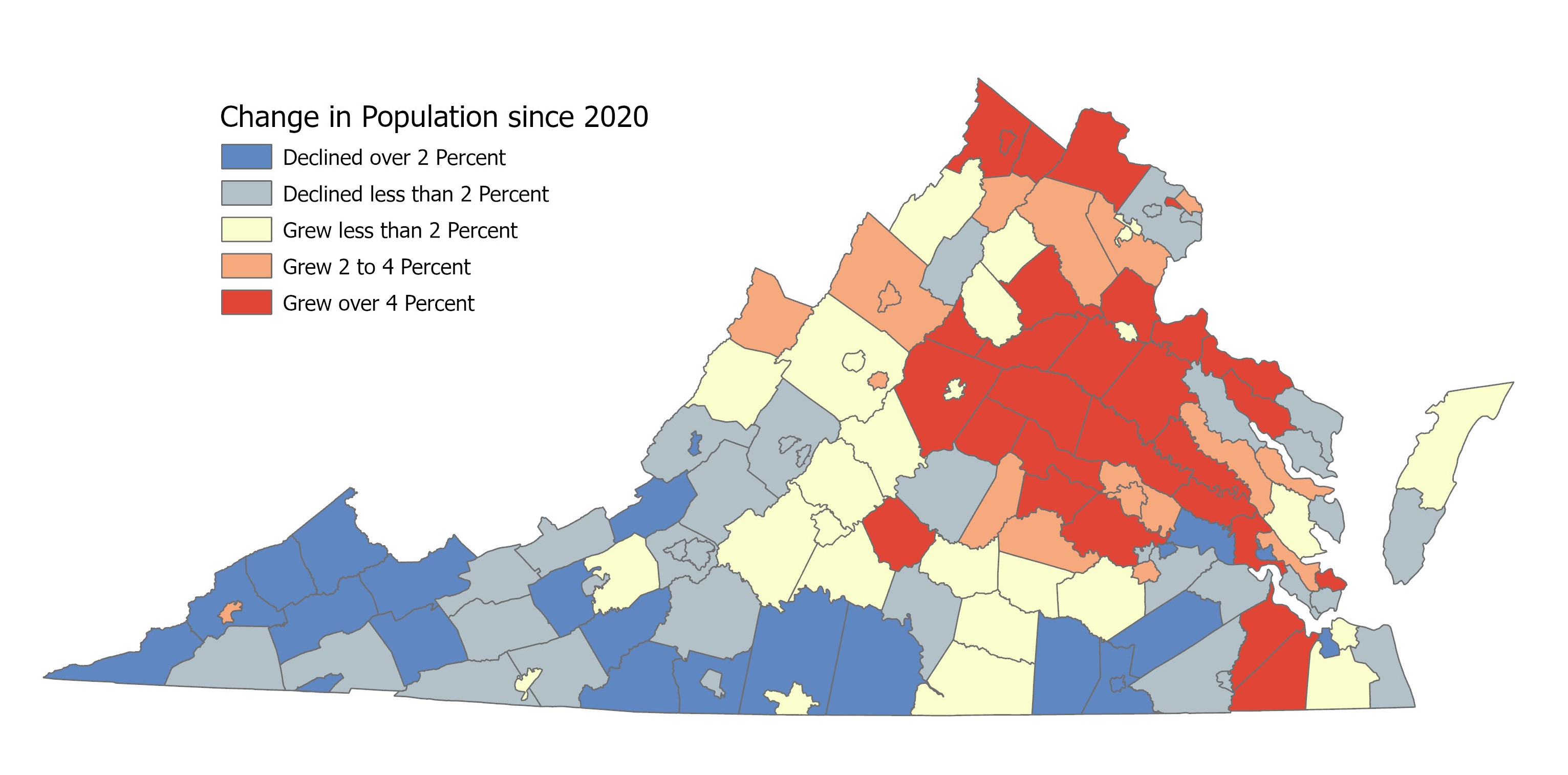

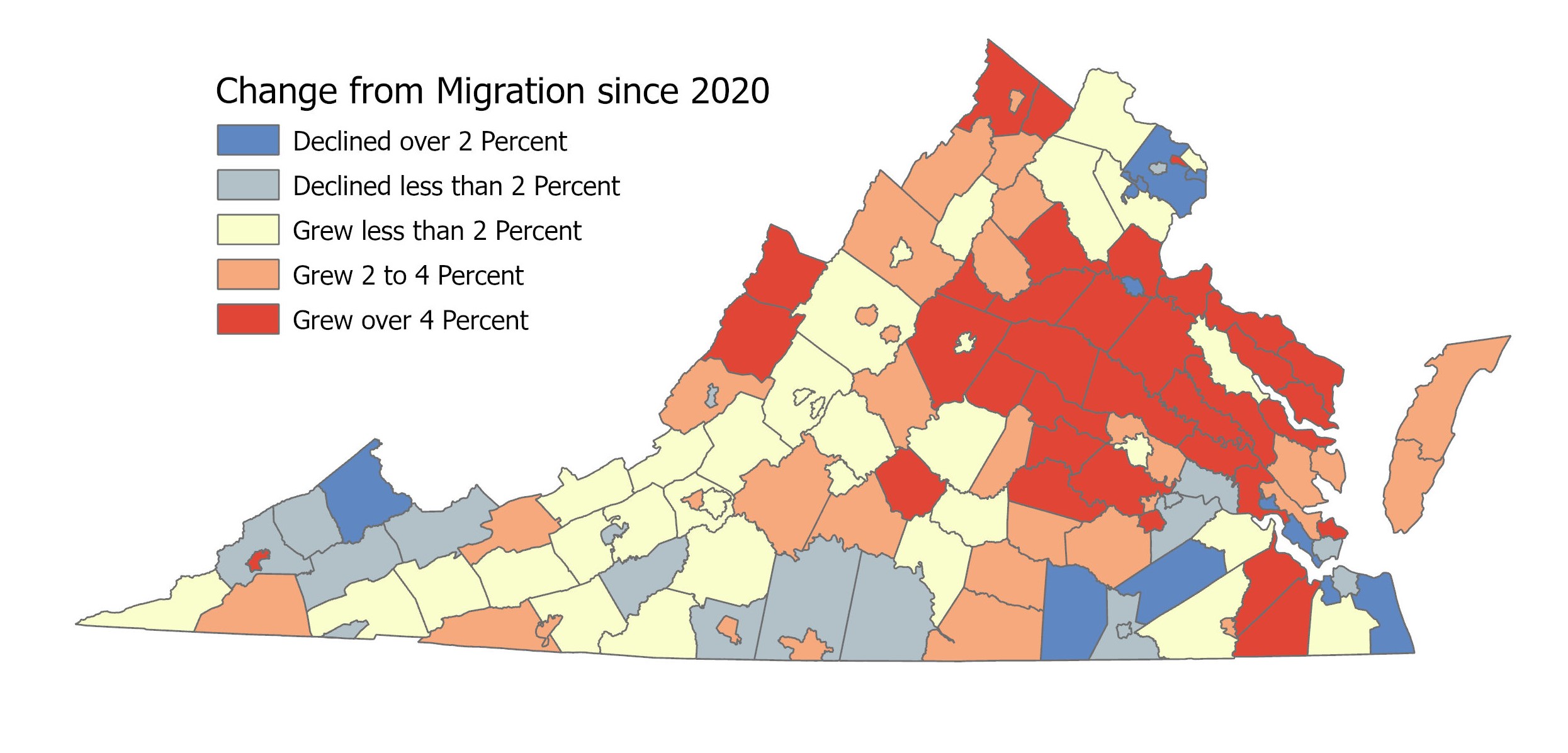

In all, 17 localities that lost population in the 2020 census are now gaining population — mostly in Southside and counties along the Chesapeake Bay — as migration remakes many rural communities.

Overall, Virginia is now officially seeing more people move in than move out, just not into parts of Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads. That marks a reversal of a decades-plus trend.

These are some of the key findings of Virginia’s most recent population estimates, which were released Monday by the Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service at the University of Virginia. Many of these trends are ones we’ve been following for several years; this data simply adds more confirmation. In some cases — such as 17 localities that have switched from population losers to population winners — we’re seeing new trends take hold.

There will be lots of insights that we can mine from this data; here are some of the biggest ones.

Virginia is gaining population two ways

There are only two drivers to population — births vs. deaths and people moving in vs. people moving out. Virginia is gaining people both ways, which represents a shift because for about a decade Virginia saw move people move out than move in. We have now multiple datasets that show that trend has reversed on the statewide level (although some localities continue to see more people move out; we’ll get to those).

From the 2020 census to July 1, 2024, the end point for this data, Virginia added 160,125 people — a demographic surplus of 61,734 more births than deaths and 98,391 more people moving than moving out. The state’s population now stands at 8,811,195.

Hamilton Lombard, a demographer at the Weldon Cooper Center, offers these observations: “Virginia’s growth accelerated from fewer people leaving, an improvement in the birth-death balance as we get further from the pandemic and higher immigration over the last few years.” (This latest data does not break out how many of those moving into Virginia are immigrants, but separate Census Bureau data has said that without immigration, Virginia would be losing population.)

Fairfax County (and some other parts of Northern Virginia) continue to lose population

That’s the bad news: Since 2020, Fairfax County, Fairfax city and Alexandria have all lost population. Here’s how unusual that is: Fairfax County hasn’t lost population in an every-10-years-census since the 1830 count documented what happened in the 1820s.

These three localities have lost population for only one reason: Lots of people are moving out. All three see more births than deaths, but not enough to overcome all those moving vans headed out. Fairfax County is much like Texas; it’s so big that any measurement there is going to be big. Still, since 2020, Fairfax County has seen 29,722 more people move out than move in — that’s the equivalent of the city of Winchester disappearing. Or Mecklenburg. Or Smyth County. Or Wythe County. The problem may not be so much people moving out but not enough people moving in — because of high housing costs.

The better news: Fairfax County isn’t losing population at the rate it has been, for the reasons Lombard cited above — out-migration is slowing and births are up. Two years ago, Fairfax’s population was down 10,544 from the 2020 census. This year it’s down just 714. At that rate, maybe by next year, Fairfax will be gaining population again. Still, at the moment, Fairfax is in the declining population category.

This matters because Northern Virginia is the state’s economic engine and produces the biggest share of tax revenue in the state — tax revenue that helps subsidize rural school systems that depend on state funding. Any loss of population in Northern Virginia, especially Fairfax, endangers that revenue.

Virginia Beach continues to lose population

Fairfax County matters because it’s the state’s largest locality. Virginia Beach matters because it’s the state’s third largest locality. All localities matter, of course, but when we’re talking about economic impacts, what happens in the biggest localities matters a lot more than what happens in smaller ones.

Virginia Beach has been losing population for the same reason that Fairfax has — lots of people are moving out. Births outnumber deaths, but not by enough to make up the deficit caused by out-migration. While out-migration is slowing in Fairfax County, it’s not in Virginia Beach, at least not at an appreciable level.

The exact figures: Since 2020, births in Virginia Beach outnumber deaths by 5,826, but the net out-migration is -12,331. The bottom line: Since 2020, Virginia Beach’s population is down -6,505. No other locality has lost that many people since the last census. On a percentage basis, Virginia Beach’s -1.4% decline since the last census is steeper than some localities in Southwest Virginia, which typically has the biggest population decline percentages.

The fastest-growing parts of the state are generally between Winchester and Suffolk

This isn’t new; this has been taking place for some time, but we still need to say it: Northern Virginia is no longer the fastest-growing part of the state. Communities within commuting distance of Richmond are. On a percentage basis, the fast-growing places since 2020 are now New Kent County (16.8%), Goochland County (11.2%) and Louisa County (10.2%). In terms of actual people, the locality that has added the most people is Chesterfield County (population up 30,277 since the last census), followed by Loudoun County (18,258), Prince William County (15,649) and Stafford County (10,528).

To give some sense of scale, I noted that Fairfax had essentially lost population on the scale of Winchester. Since 2020, Chesterfield County has essentially added that Winchester-size population. Some other notable places are gaining population, though:

Danville is now gaining population for the first time since before the collapse of the textile industry

Danville has done something that many thought it could never do: It’s growing again. The textile industry had been shrinking since the 1950s, but its collapse in the early 2000s seemed a fatal blow. Danville, like many small industrial communities, was effectively left for dead. Since then, though, Danville has set about patiently building a new economy based on advanced manufacturing. The opening of the Caesar’s casino may be what’s gotten attention, but Danville’s re-invention is much deeper than that.

These population figures underscore that. Danville’s population loss has been slowing each year. Now, these estimates finaly put Danville into the plus column. This has happened because of an unusual number of people moving into Danville. The city’s net migration is now 1,533. Because of an aging population, deaths outnumber births, leaving the city’s “natural decrease” at -1,423. That means since 2020, Danville’s population is now up by 110.

Here’s how big Danville’s net in-migration is: That 1,533 surplus of newcomers since 2000 is bigger than any other locality in Southwest or Southside. You have to go east to Isle of Wight County, northeast to Chesterfield County, or northwest to Bedford County to find a locality with more net in-migration since the last census. These trends represent an affirmation of the policies that Danville has been pursuing to remake itself.

The Lynchburg area is the population growth center in the western part of the state

Not only is the city gaining population, so is every locality it touches: Amherst County, Bedford County and Campbell County. For Amherst, this is a switch: It lost population in the 2020 census, now it’s gaining again. Appomattox County, which doesn’t border Lynchburg, but is within commuting distance, is also gaining population.

They’re all gaining population for one reason: Lots of people are moving in. Amherst, Bedford and Campbell all see more deaths than births (just like the Roanoke Valley and Franklin County, mentioned above) but their in-migration overwhelms all that. Lynchburg and Appomattox County are noteworthy because they’re among the few localities where births outnumber deaths. (I’ll look more closely at this in a future column.) Hold that thought; we’re coming to come back to both deaths and migration. But first:

The Roanoke Valley is losing population despite net in-migration

Every locality in the Roanoke Valley is seeing more people move in than move out, yet every locality in the Roanoke Valley is still losing population because deaths outnumber births and everything else. In Roanoke, in-migration is picking up. From 2020 to 2022, Roanoke’s net in-migration was 67. From 2020 to 2024, it’s 391, but deaths still wipe out those gains.

Franklin County continues to lose population

In the 1970s, Franklin County was one of the fastest-growing localities in the state, growing by 33.1%. Even through the 1980s and 1990s and first decade of the 2000s, its population grew by double-digit rates that often came close to 20%. In the last census, we saw that growth not only stop, but the county’s population drop. These estimates show Franklin’s population is still dropping. It’s not down much, down just 350 people since 2020, from 54,477 to 54,127, but still a decline.

The reason is the same as with the Roanoke Valley: More people are moving in than moving out, but, with an aging population, the number of deaths is high enough to wipe out any migration gains. This brings us to a larger finding that applies to a lot of localities, especially rural ones: An aging population, with a lot of deaths, makes it difficult for many localities to gain population.

Deaths obscure the large amount of migration into many rural areas

The big demographic story since the pandemic has been the large migration of people out of America’s urban areas and into rural areas — well, some rural areas. That migration has sometimes been hard to spot in the overall population statistics because of the large number of deaths in many aging, rural areas. Lombard points out these figures: “The portions of Virginia outside its three largest metro areas have had over 37,000 more deaths than births since 2020, which is masking the extent of migration into Virginia’s small towns and rural counties . . . Lancaster, on the Northern Neck, is attracting new residents at the highest rate since at least the Second World War but its population has declined since 2020 because of its birth-death imbalance. You can see the same pattern in Grayson and Scott, as well as Martinsville and Roanoke city. A number of other rural counties, including Northampton and Pulaski, are attracting new residents at the highest rate since the 1970s but have continued to decline for the same reason.”

Another place where the in-migration is large but hard to spot in the overall statistics is Mecklenburg County. On the surface, it looks as if nothing is happening there: A four-year population gain of just 14 people, which still shows up at 0.0%. Beneath the surface, though, some 1,050 more people moved into the county than moved out . However, 1,036 more people died than were born, so they almost balance out.

What you can see in the map above is that most localities in Virginia now have more people moving in than moving out. The only exceptions are a group of localities in the coal counties of Southwest Virginia, some localities in Southside, and two cities in Hampton Roads (Hampton and Norfolk).

Sussex County is now losing population at a faster rate than any other locality

For a long time, the Virginia locality losing population at the fastest rate has been Buchanan County. In the 2020 census, it lost 15.53% of its population, with Lee County second at 13.34%. In the previous population estimates since the last census, Buchanan County continued to be the state’s biggest population loser. Now, though, Sussex County has taken its place. Since 2020, Sussex has now lost 8.6% of its population. Buchanan County is now second at 6.4%, Brunswick County is third at 6.2%.

When we look closer, we see another change: In the early part of this decade, Buchanan County was losing population primarily because of out-migration. Now, that out-migration is slowing down, but with an aging population, deaths are the main reason the county is losing population. By contrast, Sussex is losing population primarily because of out-migration.

The specific numbers: From 2020 to 2022, Buchanan County saw 426 more deaths than births and 495 more people move out than in. However, from 2020 to 2024, Buchanan has now seen 854 more deaths than births but only 445 more people moving out than moving in. Those numbers suggest that in the past two years, we’ve seen a slight reversal of Buchanan’s out-migration. If that holds, that would be a welcome trend in Buchanan County.

I’ll have more insights from this data in future columns.

Your weekly update of political news and analysis

I write a weekly political newsletter, West of the Capital. You can sign up for that or any of our other free newsletters below: