A tree once grew through a burned-out roof of the old Virginia Railway Passenger Station at Jefferson Street and Williamson Road. Michael Friedlander passed it every time he drove a prospective employee from the airport to the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute.

It was not great for recruiting. Friedlander called Chris Morrill, who was then Roanoke’s city manager.

“I remember telling Chris, ‘The first thing they see is that roof and that tree,’” Friedlander recalled. “I said, ‘I’m going to go over there and put a blue tarp over that whole thing.’

“I’m used to that in Houston after hurricanes. And anyway, he got some people together. They did something.”

That’s a small example of how Roanoke has responded to, even fostered, its biotech economy growth. City managers have made moves that helped a Virginia Tech and Carilion Clinic partnership establish a footprint in the city, then grow from it.

Mayors and city council members have been in on the act as well, said Friedlander, Fralin Biomedical Research Institute’s founder and executive director. Some of it has surprised Friedlander, who came to Roanoke in 2010 from Houston. He was a neuroscientist and administrator at Texas Medical Center, the world’s largest medical complex. He taught at Baylor University.

He had a recent meeting with some foreign visitors who marveled that then-Mayor Sherman Lea attended a reception to welcome them. That wasn’t the sort of thing that happened in Houston. Friedlander had never met that city’s mayor. He didn’t know its city manager. He hadn’t talked to Houston’s city council.

Friedlander has had the opposite experience in Roanoke.

“I’ve never been as involved with the community leadership and government as I am here,” he said.

Houston, population 2.3 million, is an oil town where the giant hospital and its accompanying biotechnology scene are one facet. In Roanoke, population 99,000, biotechnology has become economically crucial.

Railroads built Roanoke, but Norfolk Southern methodically deemphasized the “Magic City” that it had sparked, setting the city on a decades-long decline. Municipal leaders looking for new avenues decided at the turn of the century to seize on technology. At the same time, Virginia Tech and Carilion leaders were looking to partner on medical education and research.

Tech’s president at the time, Charles Steger, and then-Carilion CEO Ed Murphy dreamed up the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine. A couple of attempts at a biotech research hub ultimately resulted in the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC, which received key funding — and its name — from Roanoke businessman and philanthropist Heywood Fralin.

A foundational event, Fralin and others say, came in 2008, when then-Del. Lacey Putney championed the Virginia Tech and Carilion projects in Roanoke as part of a $2.6 billion bond package. Putney, an independent from Bedford County, chaired the House Appropriations Committee at the time and stood up for medical research and education here when others outside the region opposed it, Fralin said.

“He knew what was happening here. … It was an opportunity that he was not going to let pass,” Fralin said of Putney, who died in 2017.

By then, the city and its former top executive, Darlene Burcham, had already moved to acquire property that became Riverside Center, where the med school and research center stand, along with surrounding commercial property that serves faculty, staff and students there.

Burcham and other city leaders including her city manager successors, Morrill and Bob Cowell, have led the city to invest in education and other programs to build and retain a tech-able workforce. The latest project is renovating a former Carilion building, to house labs that could be crucial to keeping spinoff companies in town.

Friedlander, observing efforts through several city administrations, managers and other key figures, sees a locality that “gets that this is part of the engine that can help drive Roanoke.”

Fralin, with his wife, Cynthia — and his brother’s namesake, the Horace C. Fralin Charitable Trust — donated $50 million for the biomedical research institute. Heywood Fralin said that he had seen similar facilities spark economic transformations in cities including former steel towns Pittsburgh and Birmingham, Alabama.

Nearing 15 years since its opening, FBRI employs about 800, with an average income of $67,000 a year for all employees (salaried employees there average $105,000 annually), according to the institute. The Roanoke metropolitan statistical area’s individual income averages about $54,000, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“I felt like the region … has struck gold and had an opportunity to really change to an economy that would be far better than anything that would have ever been experienced in the region in the past,” Fralin said. “I think that great progress has been made but it’s only the tip of the iceberg.”

In 2014, Fralin reached out to the University of Virginia’s Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service. His idea in part was to gather some of the region’s leaders for conversations to help better understand the valleys’ economic future. John Thomas was part of a group that visited the region over the course of a year and engaged private-sector leaders in Blacksburg and Roanoke.

During one session, Thomas found a long conference table. On one side were Roanoke people. Blacksburg business heads lined the other side. Many on the Roanoke side were still committed to industrial manufacturing, he said. The Blacksburg side, committed to advancing via technological innovations, had little use for cooperation with its neighbors to the northeast.

“And I’ll tell you, I’ve never seen such a tangible visualization of people committed to the industrial manufacturing world that was going out of business in most cases,” Thomas said.

The Blacksburg leaders felt little reason to interact with Roanoke. One participant told him: “The only reason we come across that ridge is to go to your restaurants. There’s nothing over here for us otherwise.”

Thomas returned recently for a meeting at Fralin Biomedical for a Richmond-based leadership program, Lead Virginia. He saw a completely changed attitude.

The move in Roanoke toward an economy that features biotech and traditional technology was more fully realized, he said. Blacksburg folks saw more than dining options in Roanoke. Leaders on both sides of Christiansburg Mountain had common topics to discuss.

“It has turned into a remarkable, remarkable venture,” Thomas said. “… I believe that what’s happened here is the most dramatic community transformation in recent Virginia history.”

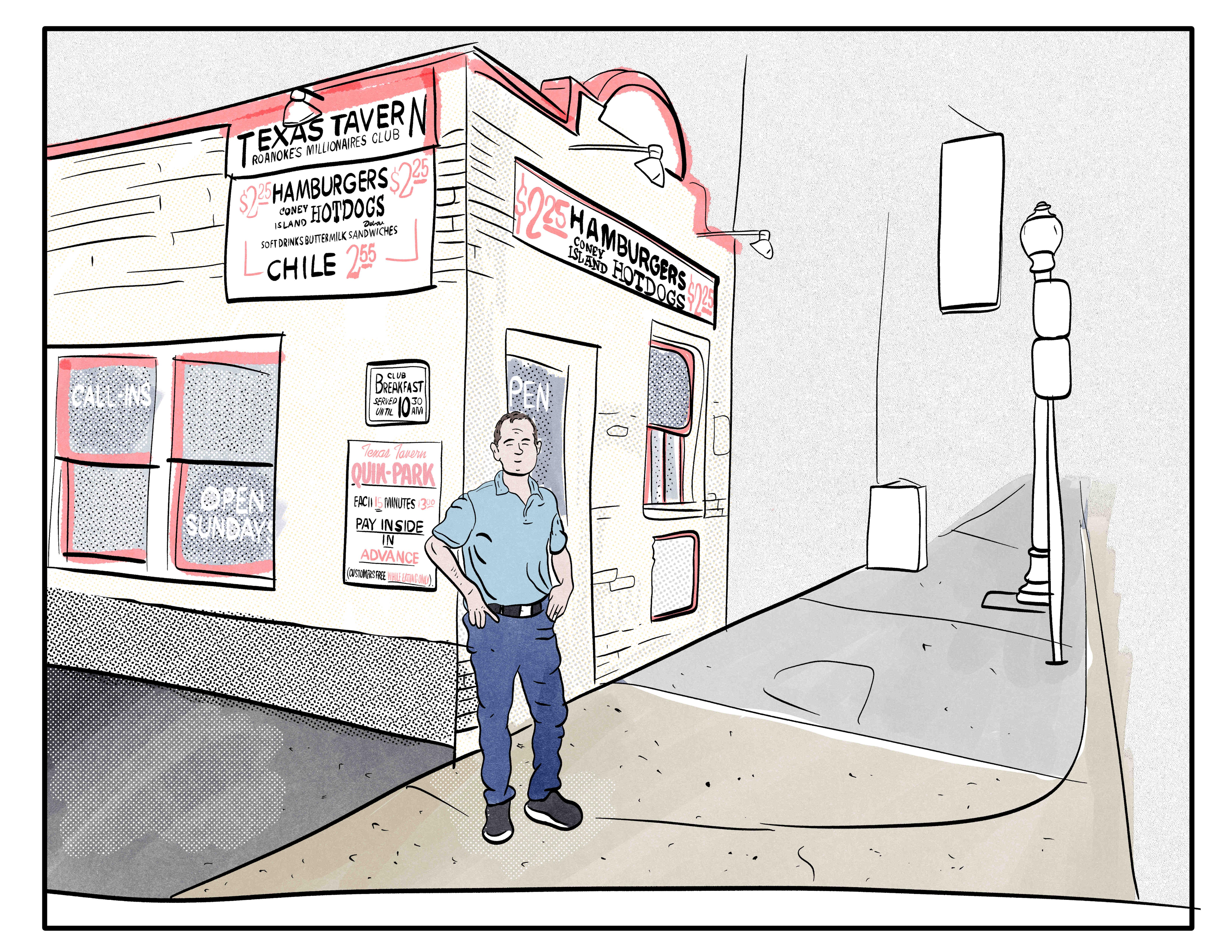

The menu remains the same. The faces are new.

In a city that changes frequently, the Texas Tavern remains immediately identifiable. The diner opened in 1930 and retains the same feel, right down to the menu. A customer sitting on a stool at the 24/7 diner’s counter sees the same list of Cheesy Western burgers, hot dogs and “chile.” The only thing that changes there is the prices.

“I could always tell if somebody’s new to town because they come in the tavern and they look at the menu for more than, like, five seconds,” third-generation owner Matt Bullington said. “When somebody does that … the first thing I do is say, is it your first time here? You move here? Or are you just passing through town?”

A fair number of Texas Tavern newcomers in recent years have been connected to Fralin Biomedical employees or the med school.

It’s part of a trend he has seen in his career and from listening to his father, the late Jim Bullington. Roanoke hasn’t been a boom town, but it has weathered economic storms, Matt Bullington said. Industries have come and gone. Corporate moves have uprooted longtime citizens. Malls once laid bare downtown, which city leaders have revitalized.

“A long time ago, there was a regular customer who was a regional bank president,” Bullington recalled. “One of his favorite things to say about Roanoke was, when the rest of the country is just going gangbusters and just booming … Roanoke is just kind of plugging along.”

It could do a lot more than that if Fralin’s vision proves out. The biomedical research center and related spinoffs could spark not just business growth but a population boom for the region, he said.

“This research institute has the ability to become one of the most recognized in the world,” Fralin said.

He added: “It’s not inconceivable to me that the Roanoke/Blacksburg population could in the next 25-plus years be in the range of two million. … It’s tremendous growth, and I think that opportunity exists.

“It all is going to depend on the community and the leaders of the community, recognizing the potential and embracing it. But I think I see the evidence of some of that beginning to happen.”

Locally, maybe so. But with a new administration in the White House, budget-cutting efforts run by tech billionaire Elon Musk appear to threaten a major portion of medical research funding via the National Institutes of Health.

This series, with stories running every Tuesday through March 11, will explore how it started with the city’s initial land investment to help create Riverside Center. It will look at city funding for education to support a biotech-centric workforce and a program to draw and retain young employees starting their careers here. And it will look to the future, particularly a new lab building the city is overseeing, to provide space for innovation — and a view of funding sources under duress.

Comments are closed.