Javier Wallace, a postdoctoral associate at Duke University, was digging through the school’s archives while doing research for one of his specializations, race in sports. He stumbled upon a mention of C.B. Claiborne, the first Black basketball player at Duke, that referred to him as “the Negro from Danville.”

That’s about as comprehensive as any archival document on Claiborne held by Duke gets, Wallace said. Looking to find out more, Wallace tracked down Claiborne and called him.

Many conversations followed that first one, and Wallace learned about Claiborne’s upbringing in segregated Danville and his basketball career at the city’s Black high school, his decision to go to Duke and his subsequent participation in the fight for equal rights on campus, on and off the basketball court.

“This person was more than ‘the Negro from Danville,’” Wallace said. “It was that limitation of Duke’s archives that was holding this story back.”

This sparked the idea for a mini-documentary on Claiborne, who led an extraordinary life even after paving the way for change at Duke, going on to earn postgraduate degrees from Dartmouth College, Washington University in St. Louis and Virginia Tech.

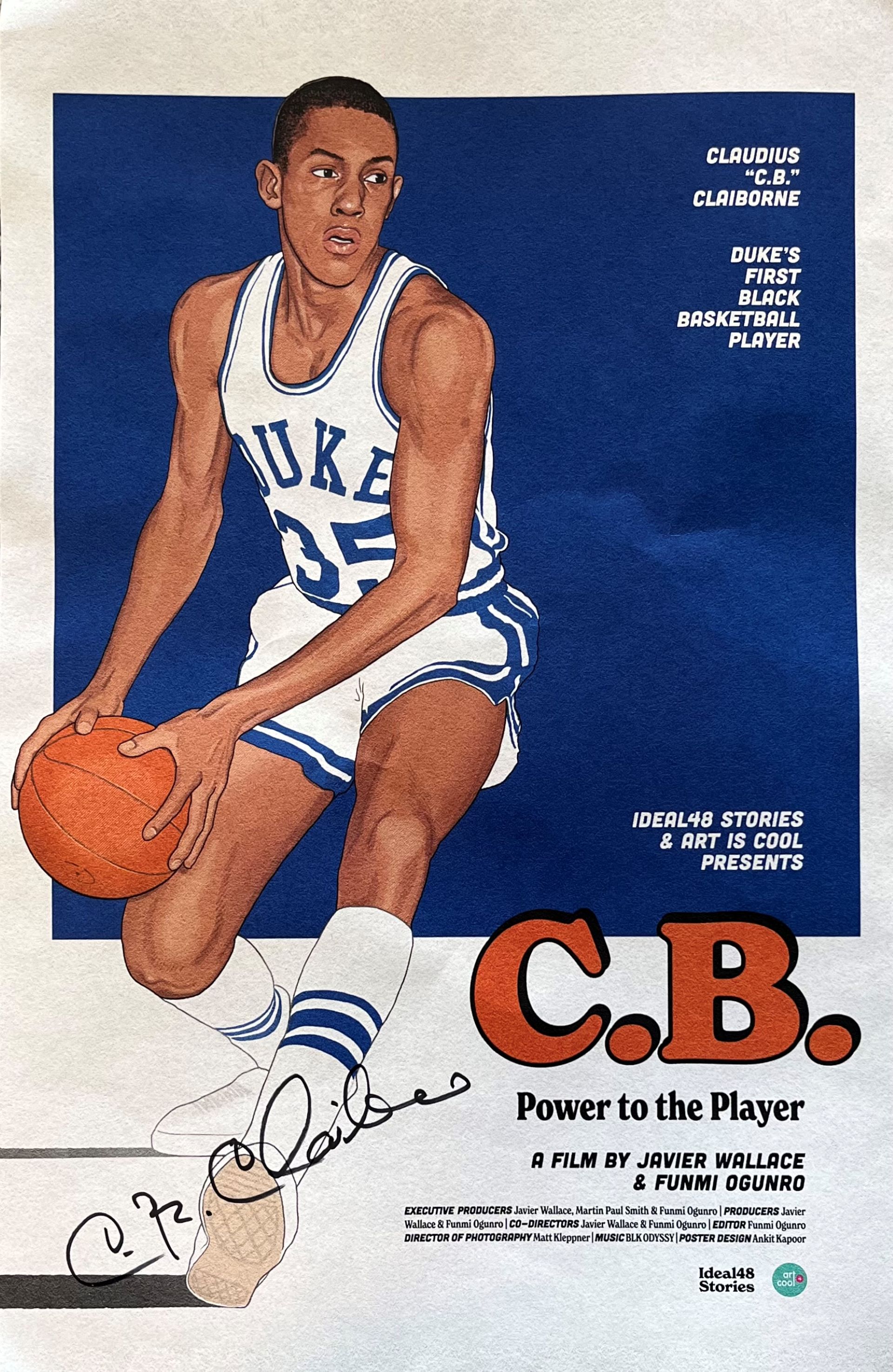

The 16-minute film, “CB: Power to the Player,” screened for the first time Wednesday night for an intimate audience of about 30 people. It was co-directed by Wallace and film editor Funmi Ogunro.

Claiborne and his family attended the screening on Duke’s campus, coming from their home in Houston, where Claiborne is a professor at Texas Southern University, a historically Black school. They were joined in the audience by faculty, athletes and alumni who had participated in the civil rights push on campus.

Many thanked Claiborne for taking the first step to integrate athletics at the university.

“I don’t exist here, if it isn’t for someone like him, who lays his life, his future, his career on the line for a person like me,” said Martin Paul Smith, a Black professor of education at Duke, who interviewed Claiborne for the film. “I’m forever in his debt.”

The documentary’s completion and premiere isn’t the end of the story, Wallace said. The film was selected to be shown at the Martha’s Vineyard African American Film Festival in August, and Wallace said he hopes it will soon be screened in Claiborne’s hometown of Danville.

Wallace and Ogunro also hope to produce a feature-length documentary, building on “CB: Power to the Player.”

“There is so much stuff that we wanted to include, but we had to make the difficult decision to meet the time limit,” Ogunro said. “The next phase is a feature-length film.”

Charting a path from Danville to Duke

Claiborne was born in Danville in the 1940s and attended John Langston High School in the early 1960s. Langston was the city’s Black high school until Danville schools were integrated in 1970.

“Danville was only second to Birmingham [Alabama] in terms of the violence and racism,” Claiborne said after the film screening. “Growing up in Danville, I got to experience a lot of this tension that was so prevalent in the south in the ’60s.”

He remembers segregated water fountains, bathrooms and entrances to municipal buildings, which were facts of life in Danville before the city’s intense civil rights movement of 1963.

“Danville was also the last capital of the Confederacy, and that was how the city chose to identify itself,” Claiborne said.

He was able to find an escape through athletics, playing for coach Hank Allen at Langston. Today, Langston houses a magnet high school, and the gymnasium is named after Allen, who coached the school’s basketball teams to hundreds of wins during his career.

By the time Claiborne was a high school senior, he still hadn’t given much thought to where he wanted to go to college, he said in the documentary.

“At that time, Duke was one of those schools that was pushing back [against] recruiting Black students,” he said in the film. “Generally in the ACC, they had raised the SAT admission scores so a lot of guys couldn’t get in, and they did that on purpose. I happened to have a good enough score to get in.”

The documentary also featured Doris Wilson, a guidance counselor at Langston, who remembered Claiborne’s impressive reputation as a student.

He was not only an “impeccable sportsman” but also a member of the National Honor Society, president of the senior class, and the school’s first Presidential Scholar, Wilson recalled. Claiborne remembered visiting the White House with his mother to meet then-President Lyndon Johnson after receiving this recognition.

Claiborne visited Duke’s admissions office with Allen. The university offered him financial aid, but not a basketball scholarship.

“They didn’t want to offer a Black player a basketball scholarship,” Claiborne said in the film.

He was put off by this initially, he said, because he knew he could be offered scholarships at other schools. In the 1960s, Duke was not yet the basketball powerhouse that it is today.

“But I ended up accepting the financial aid, since it meant school would be free and I could still join the basketball team,” he said. “I majored in engineering, and I played basketball. I was pretty excited.”

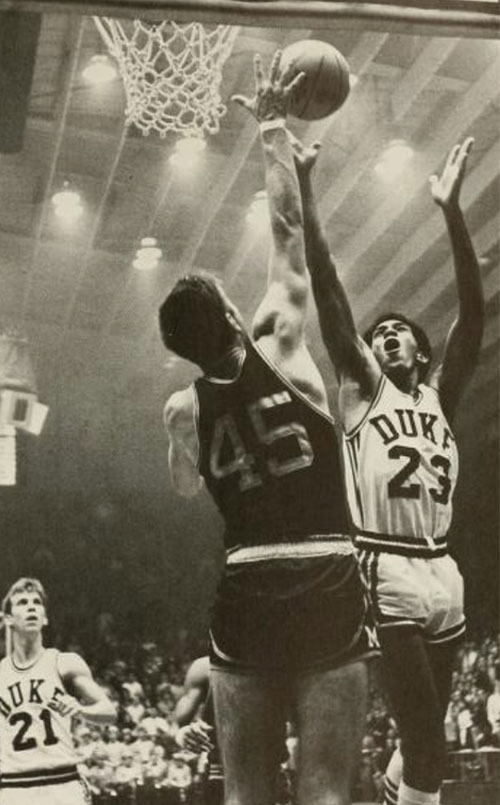

Claiborne played in 53 games and scored a total of 218 points during his three years on Duke’s varsity team, according to stats reported by the Duke Chronicle, the school’s student newspaper. At that time, the NCAA prevented freshmen from playing on varsity teams.

There were a lot of challenges on the court, Claiborne recalled. “One of the pathways of making change in the South in the ’60s was actually athletics,” he said in the documentary.

He said he often felt like he was “playing with one hand tied behind my back,” playing outside of his normal position and being bombarded with taunts and racial slurs from opposing teams, especially when Duke played in the South.

Even one of the coaches made it difficult for him at times, Claiborne said.

“I had what we called a mini-afro,” he said in the film. “The coach told me if I didn’t cut my hair, I couldn’t play. So there were times I just didn’t play.”

Claiborne was also involved in civil rights actions off of the court, participating in “study-ins” — sit-ins where Black Duke students would study — and writing a list of demands for the university.

“Wouldn’t it be nice if there was some curriculum that addressed African American issues? And so Black studies started to come up,” Claiborne said in the film. “We were also very concerned with pay for workers on campus, the cafeteria workers and the janitors. That became part of our cause as well.”

This list was ignored by the administration, Claiborne said, and “when there were no significant changes, that’s when things started to escalate.”

Black students occupied the president’s office on campus during a demonstration, and the National Guard was called on to tamp down the movement.

Over his next few years as a student, Claiborne said he gradually saw some of the changes that he and other Black students had been asking for.

“I don’t think my career here, the time I spent at Duke, was about basketball,” he said. “It was really about having an impact on our larger society.”

Condensing a legacy into 15 minutes

It was a challenge to fit so much content into such a short documentary, said Wallace and Ogunro, especially with the Civil Rights Movement as subject matter.

“We spent a lot of time going back and forth, deciding what to include in this 15-minute window that we had,” Wallace said. “How do we massage these deep topics into 15 minutes?”

The film was funded by a variety of sources, including some funding from the university, grants and a network of volunteers who worked for free or at reduced rates.

Wallace and Ogunro encouraged the audience to reach out if they could help with funding or resources for the feature-length project.

In a feature-length version of the film, “we can get into the nitty-gritty, we can talk about your childhood, about the street you grew up on in Danville … and go into more depth,” Ogunro said.

That project will be “a pretty big lift,” Wallace said, but it’s a story that needs to be told.