The year 2026 marks the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Cardinal News has embarked on a three-year project to tell the little-known stories of Virginia’s role in the march to independence. As part of this, I’m writing monthly columns about the politics of the era, written the same way I’d write them today. The events described here took place in February 1775. You can sign up for our monthly newsletter here:

In taverns, in courthouses, in homes, in churches, wherever people gather, the talk across Virginia is the same: What should we make of the latest news from London?

February is usually a time for Virginians to bundle up against the icy gales that blow in from a still-unknown west, but should we be bracing now for a different storm? Or is that storm already upon us?

In case there are still those among us who haven’t heard, Parliament has sent to His Majesty King George III a resolution that declares that “a rebellion at this time actually exists” in Massachusetts.

This is no paper resolution. This is a resolution that London seems intent on backing with force. The London Gazette reports that multiple speakers rose to declare that the people of Massachusetts “should be compelled to submit to” the “supreme” power of Parliament. Britain is now mobilizing military power to crush our fellow Colonists: Military men have trooped through the palace at St. James’ to kiss the king’s hand and take their leave. According to the London Gazette: “Orders are given for all the ships which are destined for America and Newfoundland, to take on board their full complement of seamen and soldiers immediately.” A correspondent from Ireland tells the Gazette: “The transportation of so many battalions, to North-America, is a measure which has thrown the people into the utmost consternation.”

Make no mistake: Britain means to make war on Massachusetts.

The question that now hangs over us: Does Britain intend to make war on us, as well?

The immediate cause of dispute may be the Bostonians who dumped imported tea into the harbor to protest certain taxes, but we are not exactly disinterested bystanders in this conflict. Three of the four so-called Intolerable Acts that Parliament passed in 1774 to crack down on the protesting Bostonians were aimed strictly at Massachusetts, but they raised questions for all the Colonies: If Britain can infringe on the rights of one Colony, it can infringe on the rights of all of us. Indeed, Parliament hasn’t been content just to punish Massachusetts. The Quartering Act, which allows Britain to commandeer private property to house troops, applies in all Colonies.

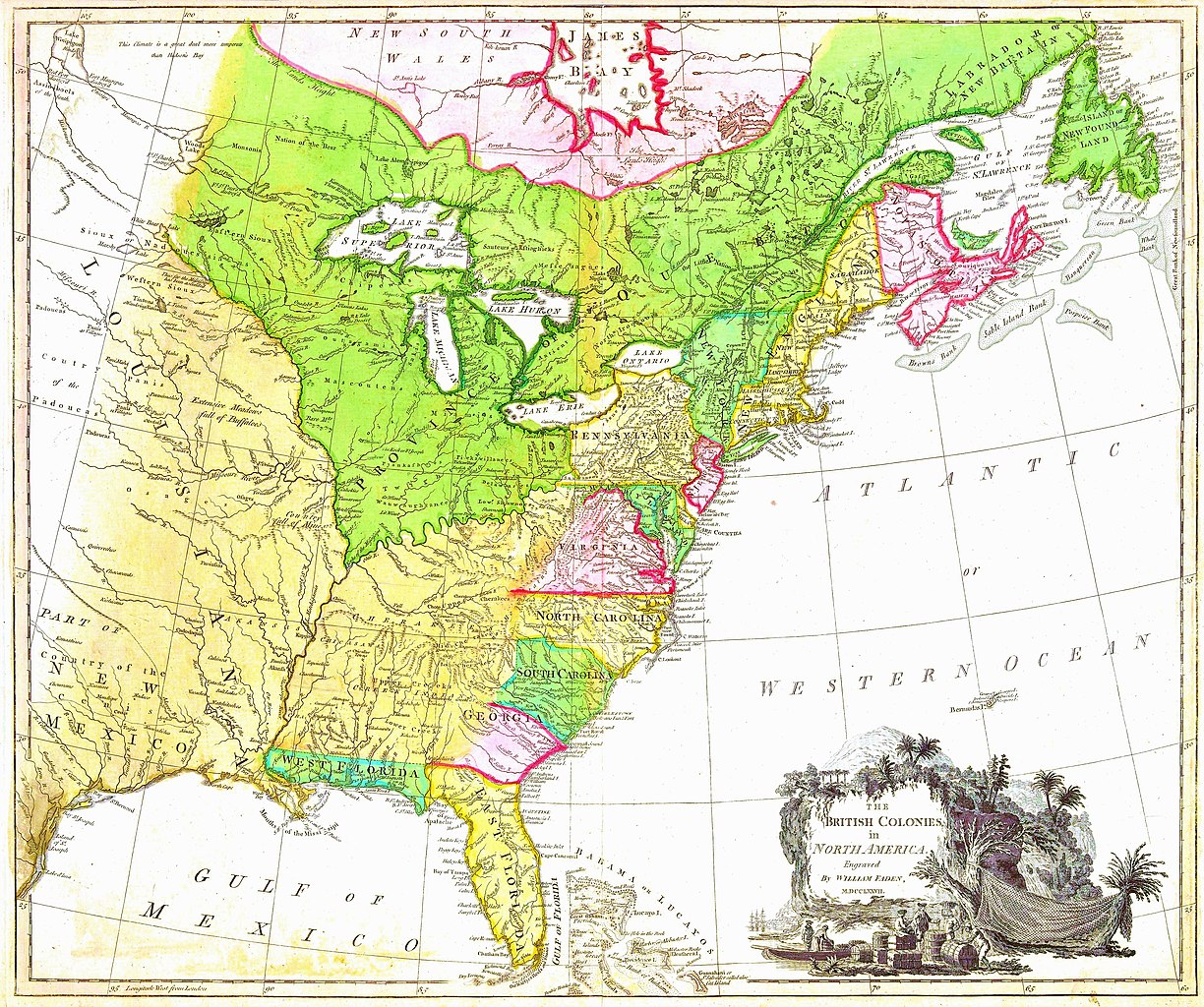

Then Parliament followed that with the Quebec Act, which takes land that Virginia claims west of the Ohio River and arbitrarily assigns that territory to the French-speaking province that Britain won from France in 1763 — with Virginia blood, I might add. (See my previous dispatch on the outrage that act produced.) If that act holds, then the land claims of many leading Virginians (and the land desires of many lesser Virginians) are now blocked. Just last year, Virginians fought a war — Lord Dunmore’s War — to push back the natives who have interfered with Virginians floating down the river toward new homes in the lands some call Kentucky. Was all that for naught?

Massachusetts has been under a creeping military occupation for some time now. A British general, Thomas Gage, now presides as governor. He’s consolidated British garrisons from Philadelphia to Newfoundland in Boston; an admiral’s fleet is already anchored in the harbor. Last fall, he seized gunpowder from the largest gunpowder storehouse in the Colony, lest it be used against his troops. (His troops also grabbed some cannons and brought them back to Boston, as well.) Some thought that seizure would spark war. It didn’t, although it did prompt local militias to mobilize and spooked Gage enough that he wrote London to send more troops: “If you think ten thousand men sufficient, send twenty; if one million is thought enough, give two; you save both blood and treasure in the end.”

Gage was somewhat overwrought, but now the British Parliament has crossed both a rhetorical and a legal line by declaring the Colony to be in rebellion. If that’s how London sees things, the outcome is clear: Rebellions, if they exist, must be crushed, lest they spread and succeed.

If war comes to Massachusetts, it will inevitably come to us, as well. Twelve Colonies — from South Carolina to New Hampshire — sent delegates last year to a Continental Congress, which called upon Colonists to stop importing most British goods in a bid to bring economic pressure on London. And now London’s response? Military pressure on Massachusetts!

If blood is shed, let history know that it was Britain that took this fateful step, not us.

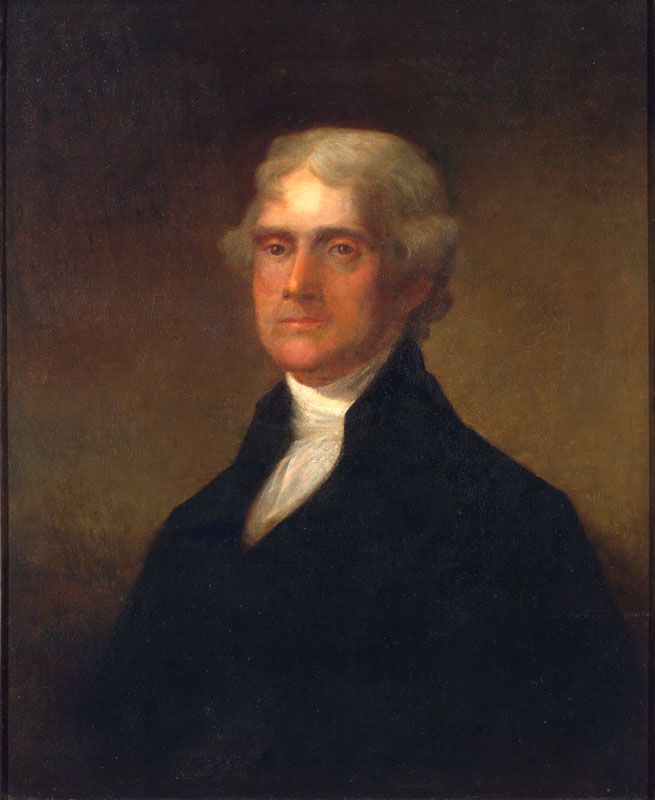

Until now we have been punctilious — some might say too punctilious — in observing non-importation movement. Consider the case of Thomas Jefferson, the Albemarle County lawyer, planter and member of the House of Burgesses. As a “conscientious observer” of the boycott of British goods, Jefferson recently sent a letter to some fellow legislators to seek their advice on an “act of mine which might wear an appearance of contravening” the boycott. Jefferson informed his colleagues that last May he wrote to a British company to order “14 pair of sash windows to be sent me ready made and glazed with a small parcel of spare glass to mend with.” Three months later, Virginia legislative leaders called for a boycott of all goods Britain. By then, Jefferson wrote, it was too late for him to countermand his order. The windows are likely to arrive soon, and Jefferson asked his fellow Virginians for guidance: Would accepting these windows, ordered before the boycott, violate its provisions?

We have not yet heard what advice Jefferson was given, but windows may soon be the least of his worries.

In my last dispatch, I wrote that the leaders of Fincastle County were meeting and were expecting to join the long list of Virginia counties that have passed resolutions denouncing Britain’s handling of its American Colonies. (Modern editor’s note: Fincastle County existed from 1772 to 1776, when it was divided into Montgomery, Washington and Kentucky counties. Its county seat was in modern-day Wythe County.)

Those resolutions have now been published in Williamsburg, and they go beyond anything previously resolved elsewhere. For the first time, a Virginia county has declared its willingness to fight to protect the liberties that Virginians feel they are guaranteed under the 1689 English Bill of Rights. While Fincastle is the first county to make such a provocative declaration, this is not the first time we’ve heard this language. Not long ago, the Virginia soldiers at Fort Gower on the Ohio adopted something similar. Those men in Fincastle County and at Fort Gower should not be disregarded simply because of their distance from Williamsburg. They know what fighting entails: Many of them have just returned from Lord Dunmore’s War.

This feels like two ships on a collision course: One by one, Virginia counties are asserting their rights; Fincastle County has simply used more martial language than most. On the other side of the Atlantic, Britain is now marshaling its military to suppress what it deems a “rebellion” in Massachusetts.

Meanwhile, the parade of counties passing resolutions continues. Augusta County is the latest. Like Fincastle County before it, the leaders of Augusta County have now resolved to risk “our lives and our fortunes” to defend their rights.

Can this conflict be avoided? Dare we ask: Should this conflict be avoided?

We shudder to think about what may lie ahead.

Other dispatches

Dispatch from January 1775: Economic boycott of Britain helps Virginia farmers get out of debt as tensions simmer

Dispatch from 1774: Virginia soldiers become the first to declare they’re willing to fight for liberty

Dispatch from 1774: Colonies convene a Congress, vote to boycott British goods

Dispatch from 1774: Settlers massacre Mingo near Ohio River, prompt ‘Lord Dunmore’s War’

Dispatch from 1774: Britain gives Virginia’s western lands to Quebec

Dispatch from 1774: More than 30 Virginia counties pass resolutions to protest British response to Boston tea-dumping

Dispatch from 1773: Smuggling in Rhode Island prompts Virginia to do something revolutionary

Dispatch from 1772: Britain vetoes Virginia’s vote to abolish transatlantic slave trade

Dispatch from 1769: Governor dissolves House of Burgesses; Virginia vows boycott of British goods

Dispatch from 1766: A sensational murder at Mosby’s Tavern highlights how much Virginia’s gentry is in debt to Britain

Dispatch from 1766: In Tappahannock, the Stamp Act prompts threats of violence

Dispatch from 1765: Stamp Act protest prompts House speaker to accuse new legislator Patrick Henry of treason

Dispatch from 1765: Augusta County mob murders Cherokees, defies royal authority

Dispatch from 1763: Despite cries of ‘treason!,’ Hanover County jury delivers rebuke to the church — and the crown (The court case that made Patrick Henry a celebrity.)

Dispatch from 1763: King’s proclamation has united often opposing factions in Virginia (Opposition to the king’s proclamation forbidding western settlement.)