The year 2026 marks the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Cardinal News has embarked on a three-year project to tell the little-known stories of Virginia’s role in the march to independence. This project is supported, in part, by a grant from the Virginia American Revolution 250 Commission. Find all our stories from this project on the Cardinal 250 page. You can sign up for our monthly newsletter:

The life story of William “Billy” Flora, a Black man and celebrated Revolutionary War hero, illustrates the paradoxes of America’s founding.

Flora was born in Portsmouth in 1755 to Mary Flora, a free Black woman. Black children inherited the status of their mothers, free or enslaved. As a young man, Flora joined the Patriot cause in 1775 and served as a private in the Virginia Militia.

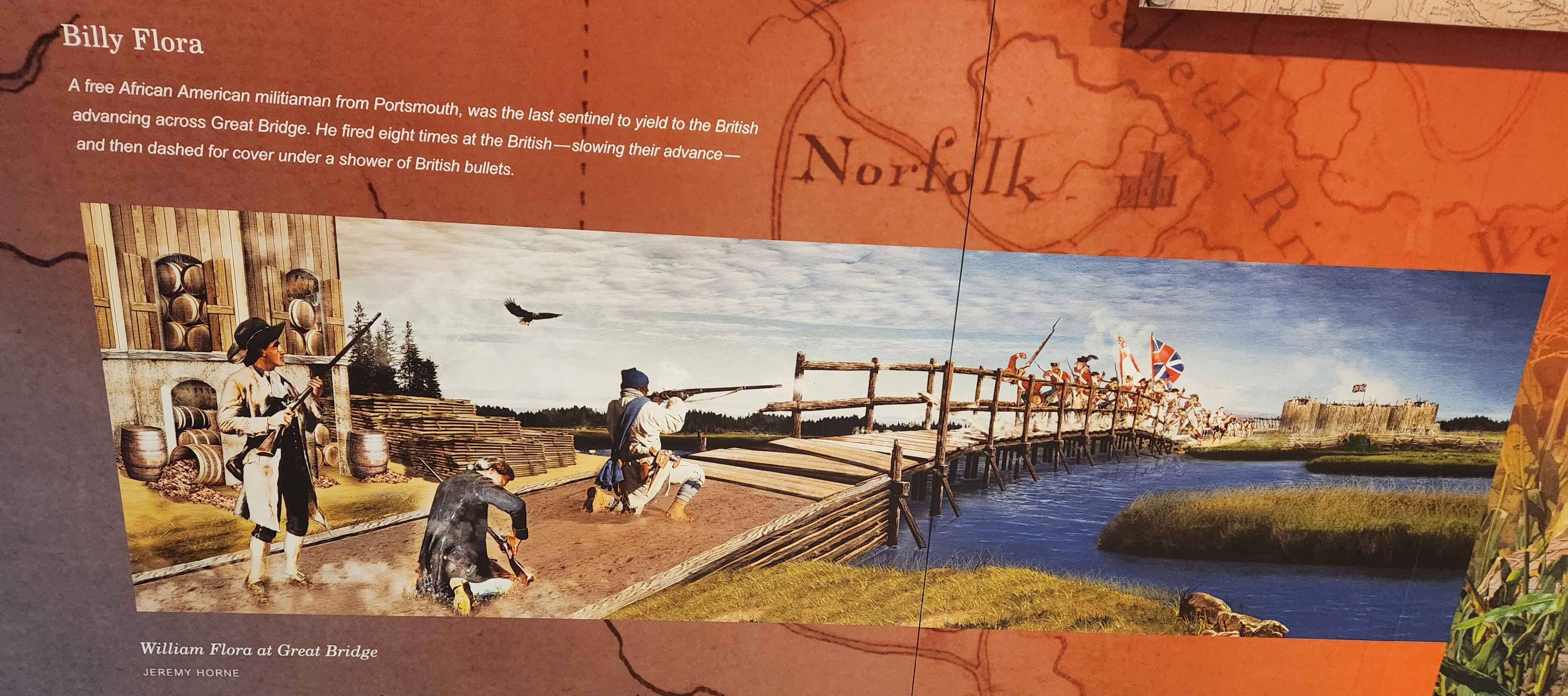

History remembers Flora as the hero of the Battle of Great Bridge. A sentry facing an onslaught of volleys, he fired multiple shots at oncoming British forces from behind the scant cover provided by a pile of shingles. Flora successfully slowed the enemy’s advance, giving Patriots crucial time to man their defenses.

Flora continued to serve throughout the Revolutionary War and during later conflicts in 1807 and 1812 and was lauded for his bravery by both Black and white residents of Portsmouth. But Flora was a Black man — he didn’t enjoy the same rights as his white brothers in arms.

A 1723 law denied free Black men the right to vote for representatives in Virginia’s Colonial-era legislature, the House of Burgesses. Flora, who ran a successful livery business in Portsmouth after the war, was one of the first Black people to own property in the city, and paid taxes on his holdings, records show. Though a Revolutionary War veteran, Flora remained unable to vote for representatives in the new government he fought to create and was taxed to support.

Ironically, some of the first cries for revolution were boycotts of British goods in protest of Parliament levying taxes on Colonists, who could not elect members of Parliament. It wasn’t until after the Civil War that the 15th Amendment finally gave voting rights to Black men, albeit with significant obstacles at the polls.

A new, independent America didn’t mean freedom for Flora’s enslaved family. Flora married an enslaved woman and later purchased her freedom and that of their children.

American revolutionaries espoused ideals of liberty and freedom from British rule, while simultaneously disenfranchising and enslaving Black people, said Harvey Bakari, Black history curator at the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation.

“That is … the paradox Flora would have to deal with, even though he’s fighting valiantly, putting his life on the line,” Bakari said. “What would that say about Black people feeling like they belonged?”

We also have a podcast with Bakari about Billy Flora. Find it and other Cardinal 250 podcasts here.

The battle

On the early morning of the Battle of Great Bridge on December 9, 1775, Flora probably shivered from the cold in a wool coat, musket in hand. He “crouched in the lee of a pile of shingles next to a burnt-out building” on a marshy shore of the Elizabeth River, Norman Fuss wrote in the Journal of the American Revolution. Fuss referenced maps from the time, letters from British officers at the scene and other primary sources to write a detailed battle description.

Flora was posted near other sentries whose job it was to alert nearby troops of the 2nd Virginia Regiment and the Southern Minute Battalion of any movement from nearby British forces. About 70 yards ahead of Flora, at the end of the “Great Bridge,” were red-coated British soldiers in their palisade fort, named Fort Murray after the Royal Governor of Virginia, John Murray, know as Lord Dunmore, Fuss wrote.

About a quarter-mile behind Flora were Patriot fortifications, a breastwork shielding 60 men on the northern end of the island that was home to the town of Great Bridge. Another quarter of a mile behind that, a main force of 650 men was camped near a local church.

When Flora saw men replacing planks the British had removed on the bridge, he knew they were preparing to attack the Patriot fortifications. He fired his musket. A few shots from other sentries rang out. His comrades on watch ran to warn the fore guard, but Flora stayed at his post.

“Realizing that the firing of the sentries well might be ignored because of the constant sniping that had been going on for days, Billy resolved to delay the British for as long as he could,” Fuss wrote.

He fired repeatedly from behind the pile of shingles, while taking fire from an entire platoon — a total of 20 British soldiers — before he broke cover and ran for the safety of the Patriot breastwork.

“British guns flying all around him, Billy scrambled over the plank that gave access to the breastwork,” Fuss wrote. “But before dropping down to safety, he paused to take up the plank and pulled it within the breastwork … to deny it to the approaching enemy.”

The British crossed the bridge while being fired by the fortified Patriots, and were vulnerable to attack, as they couldn’t stop to reload in safety. They resorted to foolishly charging at the palisade with bayonets.

Though the Battle of Great Bridge was over in minutes, and you probably didn’t learn about it in school, it was arguably one of the most pivotal engagements in the Revolutionary War.

In the following days, Patriot forces drove Royal Governor Lord Dunmore and his forces out of the Colony. Their exit allowed Virginia, “the most populous and wealthiest of the 13 nascent states in the United States,” to provide General Washington with thousands of troops and munitions, Fuss said in an interview with Cardinal News. And Chesapeake Bay was key to bringing in supplies from international allies, he added.

“The argument can be made that without Virginia being free of British presence for six years, in 1781, we would not have had an army to march South with the French to confront Cornwallis in the action that won our independence,” Fuss said.

Black soldiers in the Revolution

Flora had taken up arms against other Black men at Great Bridge, who were part of a fighting force called the Ethiopian Regiment. With the promise of freedom to Black men enslaved by rebels, Lord Dunmore drew more than 1,500 runaway slaves into the ranks of the Ethiopian Regiment. Most of these men never lived to see if Dunmore would keep his word; communicable diseases, possibly smallpox or typhus, killed two-thirds of them within a year.

In other Colonies, British forces later offered freedom to men enslaved by rebels in exchange for military service. An estimated 20,000 runaway slaves joined Loyalist forces. Only 5,000 Black men, free and enslaved, served in the Continental Army, mostly within integrated units.

Many enslaved people in the American Colonies believed slavery had ended in Britain, which may have led most to side with Loyalists. News from across the Atlantic about the unprecedented outcome of a legal case in London, brought by an enslaved man against his master, gave hope to enslaved people in America. James Somerset, an enslaved man living in London, had successfully sued his owner for his freedom. Though the case didn’t abolish slavery outright, it had a major impact, wrote John Hannigan, a Tufts University historian.

“Many individuals in America interpreted the case as an indictment of slavery and evidence from runaway advertisements indicates that slaves themselves understood the case as having abolished slavery in Great Britain,” he wrote.

Enslaved people who cast their lots with the Patriots were runaways or enrolled in exchange for liberation after the war. Often, they were forced to serve as substitutes for their masters or were slaves owned or hired by the government.

In response to fears from Southern whites that arming Black people would spark slave revolts, the policy regarding free Black men fighting in the Continental Army changed throughout the war. In 1775, Washington ordered that free Black men not be recruited into the Continental Army, though many had already served. Later, as the Patriots needed more firepower, Washington allowed Black veterans to reenlist. But why may Flora and other free Black men have joined the Patriot cause?

When Flora enlisted, all men ages 16 to 60 were required to join the Virginia Militia, but Flora and many other free Black soldiers continued to fight beyond their initial terms. Flora served throughout the Revolutionary War and with the 15th Regiment of the Continental Army during the Battle of Yorktown at the conflict’s end. After the war, he operated his livery stable on Middle Street in Portsmouth for 30 years. As was customary, the U.S. government granted him 100 acres of land in 1818 for his service throughout the war.

Free Black Patriots may have hoped that the ideals of liberty and equality that sparked the revolution would extend to them. “Flora and others are displaying a lot of valor and bravery but perhaps, he’s thinking of something bigger than himself, that if he does this, this might open the for Virginia to maybe relax their laws on free Blacks,” Bakari said. “Allow free Blacks to have the same citizenship rights as fellow white soldiers.”

Paychecks also motivated free Black soldiers, though the Continental Army faced pay shortages and inflation. For Flora, “a relationship with the white power establishment” may have been a factor, said Tommy Bogger, a retired Norfolk State University professor and historian.

For many free Black men, joining the Continental Army may “not have been based on philosophy but on common sense, based on personal relationships,” Bogger said.

Camaraderie and pride may have also been a factor, Bakari said. “I think there’s a sense of manhood that one could not obtain any other way; you are fighting as a soldier,” he said. “I think there’s probably a sense of manhood that slavery and discrimination against free Blacks took away.”

In the first few years after the Revolutionary War, “there was a bubble of excitement … this opportunity for things to change,” for Black people in America, Bakari said.

Black Patriots were celebrated for their valor in battle, marching proudly in parades on July Fourth. A Pennsylvania newspaper advertisement for a piece written by an unknown Black author, published in 1782, the year before the war’s end, is one of the earliest mentions of the words African American in print. It was in seeming acceptance of the role Black people had in creating the new nation.

Free Black Americans began building their communities. Prince Hall Freemasonry, the oldest Black fraternity in the U.S., began as a mutual aid society in 1784. Iconic Black religious institutions such as the African Methodist Episcopal Church and the African Baptist Church were established.

A 1782 legal change in Virginia that allowed slave owners to manumit the people they enslaved, without first receiving government permission, grew the number of free Black people in the state. Portsmouth had a thriving free Black community due to a shipbuilding industry that employed many Black tradesmen. Enslaved people were able to work independently to save enough money to buy their freedom, and free Black people purchased others out of slavery.

Flora’s livery business also prospered. A few years after Virginia relaxed its manumission laws, Flora bought his wife and two children out of slavery. In 1784, he purchased two lots in Portsmouth and in subsequent years, he bought and sold several houses and lots. By 1810, tax rolls show he was paying taxes on three large wagons, three two-wheeled carriages and six horses.

But progress didn’t last. A new Constitution didn’t consider the rights of Black Americans, and their sacrifices in war were forgotten as the Revolution slowly faded into history. In Virginia and other Southern states, new laws made achieving freedom harder.

“One thing has been constant from the 1600s to the 1900s: Every time the free Black population increased, there was a desire to push back,” Bakari said, “They wanted Black people just to be slaves, not free Blacks.”

In 1806, Virginia passed a law that required all newly manumitted Black people to leave the state in a year. Northern states were not welcoming to free Black Americans at this time, and leaving home meant being without the protection and ties of extended family and a free Black community and was tough economically.

At the age of 52, Flora was still a member of the Portsmouth militia. He was called to serve after an attack on the frigate Chesapeake. He enthusiastically declared that he would “be buttered” if he could not use old Betsy again, the musket he carried at Great Bridge. In 1812, he served a short stint as a home guard during the Battle of Craney Island.

Flora was fighting for a nation that was quicky clawing back the few rights held by free Black people and still held people in bondage.

“Him fighting in the war of 1812, makes me wonder, what might some of his disappointments have been in the country,” Bakari said.

Flora died in 1820, a respected and honored war hero, but the contradictions of the nation he helped found on the principles of equal rights were unresolved.