Railroads built Roanoke, but Norfolk Southern slowly but surely abandoned the “Magic City” that it sparked. City leaders looking for new avenues decided to emphasize technology.

Tech Town is a four-part series looking at how the effort started and where it is now.

Read the other articles: Introduction, Part One, Part Two, Part Three.

Roanoke looked no better than a “stepping stone” city to Ryan King.

The University of North Carolina graduate was scheduled for two days in Roanoke, where he was interviewing for a graduate research assistantship and to seek a Ph.D. After the first day, King called his wife, Danielle, and told her he thought he would skip day two.

He had worked all day in Chapel Hill before driving into Roanoke. His route took him through a neighborhood and a downtown dotted with boarded-up buildings and derelict houses. He saw decline, not opportunity.

“I was like, I don’t want to live here,” King recalled of that day in 2015. “I’m just going to come home, and she was like, don’t burn those bridges — one of many good decisions my wife has helped me make.”

He received his Ph.D. in 2021, from the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC’s Translational Biology, Medicine and Health program. By then, he had fallen for Roanoke. In November 2023, he returned to town, this time as innovation manager at Carilion Clinic. He said this is where he and his young family want to stay.

King realized along the way that Roanoke was not a city in decline, but was in fact ascendant as a medical and biotechnology research center.

“I fell in love, not particularly with what was there at the time, but the potential for what could be,” King, 31, said.

Roanoke is building out its biotechnology future in a visible way, with a multistory renovation on Jefferson Street. The city is part of another project, too, this one featuring a new room in an existing building.

Both projects focus on lab space that can keep biotech innovators in Southwest Virginia and draw new ones, people involved with the projects say.

The renovation project on Jefferson Street, when finished, will provide at least 15 lab spaces and 25 offices for life sciences and computational studies. A couple of blocks south, Fralin Biomedical Research Institute, or FBRI, will add a “clean room” space for researchers to develop biomedicines in an antiseptic atmosphere.

Erin Burcham, executive director at Roanoke Blacksburg Innovation Alliance (formerly Verge), said that this era is just getting started, but that growth is happening quickly. The research institute, the Carilion Clinic Biodesign Program at Virginia Tech and Carilion Clinic Innovation are at the forefront of a “strong pipeline of startup ideas,” she said.

“So I think we’re really on the edge of something really great,” Burcham said.

[Disclosure: Carilion and the Roanoke Blacksburg Innovation Alliance are among our donors, but donors have no say in news decisions; see our policy.]

An eye-opening article

Roanoke was at the end of its railroad era, and its Riverside Center hadn’t fully blossomed when King, then 22 with a bachelor of science in biology, showed up in town. The Gastonia, North Carolina, native, after deciding to stick around for the second day of interviews, connected with Steve Poelzing, whose lab at the research institute investigates cardiac issues. King decided he would seek his Ph.D. in town, but he still wasn’t sold on his new home base.

Then he came upon an article on the website Politico, titled “Trains Built Roanoke. Science Saved It.”

“It really was eye-opening to me because … there wasn’t a lot going on, and that article was like … it’s the end of one era, but it’s the beginning of the next,” King said.

He compared Roanoke to Chapel Hill with a new lens.

“You’re not here in this well established, well-running ecosystem, kind of like I was when I was at UNC,” he said. “You’re here at the budding beginning of something, and you can actually shape the way this looks. You’re here doing science. You’re one of the early ones.

“There’s an opportunity to get involved beyond just the classroom. There’s a chance to really build the ecosystem, and I loved that idea.”

After a stop at Ohio State University for his postdoctoral fellowship, he reached out to contacts for his next job. The timing was fortuitous. Carilion Innovation — which helps clinic employees bring their health care inventions to reality — was hiring.

The evening before the interview, the Roanoke Blacksburg Technology Council held its monthly Beer & Biotech social learning session.

“I made it a point to go out there and essentially reconnect with the whole tech community because that’s what I was so excited by,” he said.

He has been part of what he calls RBTC’s “welcoming community” ever since. It’s part of what will help the biotech scene continue to build in the region, he said.

“If somebody’s shy about getting out the first time because they don’t know anybody, they don’t have to be,” King said. “It’s a really welcoming community and … everybody’s kind of all in it together.”

Addressing big needs

Several of the RBTC regulars have created companies that do intriguing work. Their opportunities to grow in Roanoke have been limited by laboratory needs. A “clean room” space is among them.

Roanoke has combined with Virginia Tech, Carilion, Montgomery County and RBTC in a pilot project that will put some local companies to work in a modular clean room — crucial for biotech manufacturing in a contamination-free environment. A $100,000 grant from economic development initiative GO Virginia and $221,500 in non-state money will fund the project, GO Virginia has said.

Three companies that have participated in RBTC’s tech business accelerator program, RAMP, will use the space. Cancer-fighting businesses Tiny Cargo Co. and Acomhal Research, both in Roanoke, and Blacksburg-based equine therapy specialist Qentoros would likely have had to move elsewhere without it, Burcham and others say.

The space is under construction at an existing Riverside Center building, and FBRI will manage it. It’s due for completion by the end of March, said Tiny Cargo co-founder Spencer Marsh, a scientist and teacher at the research institute.

His company will use the clean room on a contract as it processes the milk exosomes it intends to apply for therapeutic use. Marsh said that his company would have to move its operations if it didn’t have such a facility in Roanoke.

“It will serve not only as a manufacturing space, but also as a teaching facility where students and professionals can learn how to operate inside a GMP (good manufacturing practices) manufacturing environment, which is quite different than operating within a lab environment,” Marsh said in an email exchange.

The project’s partners will study regional clean room needs, not only to keep businesses here, but to attract new ones. That includes developing lab talent, which is happening at Virginia Western Community College.

“I think the big storyline is we’re looking at a very foundational level on how to build biotech in the multiple elements to make it inclusive to people across the region,” Burcham said. “It’s not just for Ph.D.s. We’ve been very intentional with the partnership with the community college to focus on more frontline entry level positions in biotech.

“But these are high-paying jobs. They’re not $30,000 jobs, these are $65,000 and above.”

Some of those frontline jobs will likely be available where workers are renovating a former Carilion Clinic building on South Jefferson Street. The structure, about 40,000 square feet, is being converted to incubator lab spaces.

It stands less than a half-mile from both FBRI and the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, to its south. RAMP headquarters is equally close, to its north.

Roanoke, the Virginia Tech Corporate Research Center, Carilion, Montgomery County and Verge are project partners.

The multistory structure will feature at least 10 labs that can accommodate up to three people, four larger labs that can hold up to six people, and one shared lab with eight benches that researchers can rent, said Bradley Boettcher, innovation administrator for the city’s economic development office.

Most of the space, about 70%, will accommodate “wet lab” work of chemicals and other liquids. The rest will be devoted to “dry lab” work, which involves research centered on computer applications. The dry labs can be converted to wet, if that’s where the demand lies, Boettcher said.

Elsewhere in the building, 25 offices of varying sizes will include 11 with plumbing options for possible conversion to lab space. Three conference rooms, a multipurpose event space and a cafe will round out the building.

The tech community has long called for more real estate to incubate local research and draw life sciences companies from outside the region. The labs will cover prototype work for engineering and biology, and if the project is successful, it could lead to more large-scale lab space, Burcham told a group of Roanoke Blacksburg Technology Council members in a January presentation.

“This is a very small project on the way to a huge project in the future,” Burcham told the group at an RBTC Beer + Biotech event in Roanoke.

The state put $15.7 million into its budget in 2022 to renovate the building. Roanoke added $1.9 million to the project, and is overseeing the renovation. The Virginia Tech Corporate Research Center, which will house a smaller sibling lab facility, will run both facilities. Last month, Virginia lawmakers added $4 million to the budget this year, so the incubator labs can add clean room spaces, which already have a potential tenant. The new budget infusion would require a match from the city and a guaranteed tenant.

If a company needing clean room space agrees to move in, the city “could look to pivot and change the plans,” Boettcher said.

Renovation is scheduled for completion in 2025’s third quarter, with move-in scheduled for the fourth quarter, he said.

What remains to be done

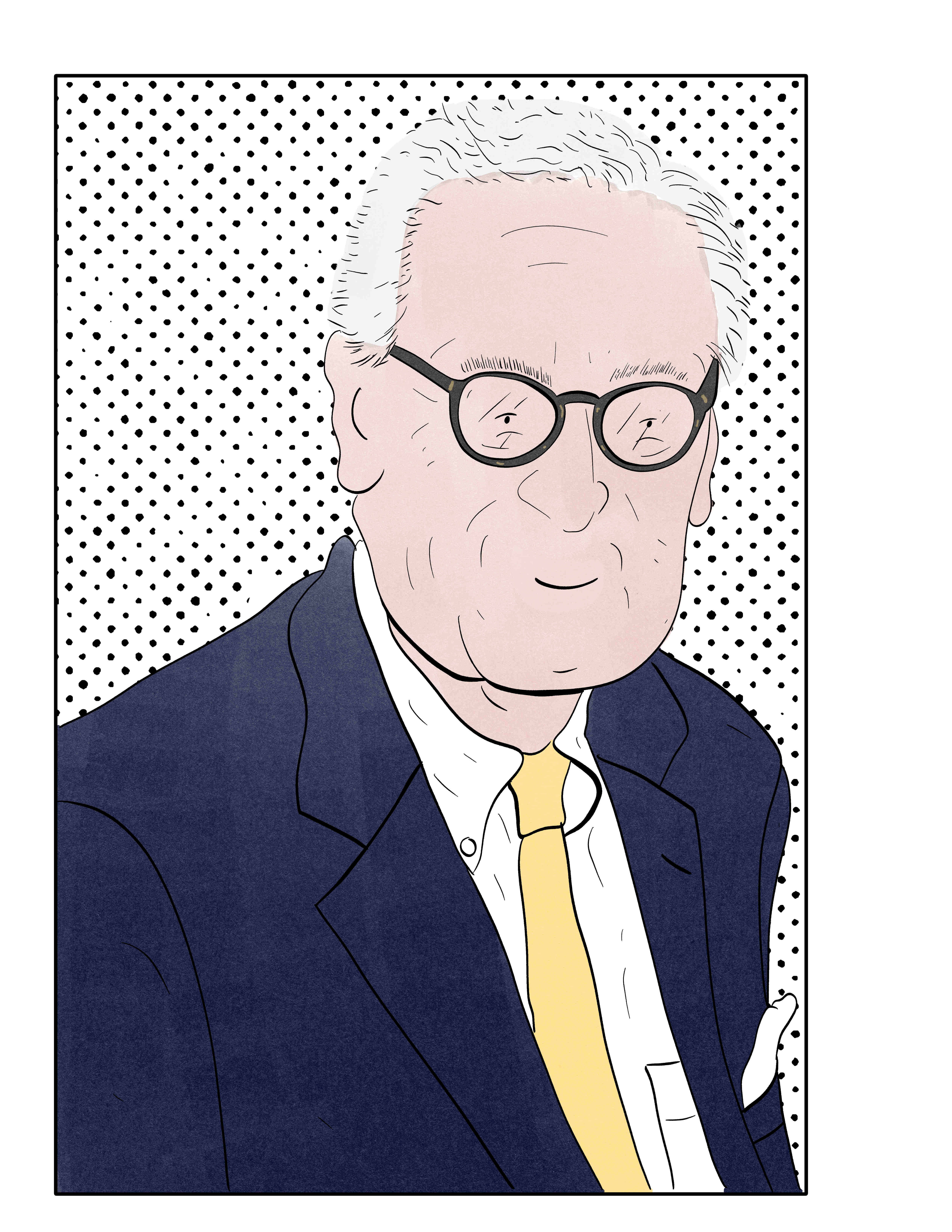

Heywood Fralin, whose family name is on the biomedical research center, is a lifelong Roanoke resident interested in the city’s financial health. He is excited about the region’s potential, with FBRI and the medical school anchoring Riverside Center, and FBRI spinning off startup businesses.

The efforts will need support from multiple governmental layers, to develop better roads and even improve air travel here.

Among possible road projects, Fralin said he would like to see a freeway connecting Roanoke to the North Carolina line, with access via ramp only. Getting from FBRI to North Carolina’s Research Triangle universities — and to Wake Forest University, which partners with Virginia Tech — should not be as difficult as it is on U.S. 220, he said.

“All of these research institutes need connectivity, “ he said. “You can take any 16-year-old that’s just learned how to drive and put them on 220, and they will tell you that road is a dangerous road and not up to standards today.”

Fralin mentioned a new group, the Blue Ridge Innovation Corridor, that is advocating for an improved 220. A couple of months after the Blue Ridge Innovation Corridor announced its presence in summer 2024, the Commonwealth Transportation Board buried its long-stagnant plans for Interstate 73, which would have upgraded the way from Roanoke to Greensboro, North Carolina.

“Now, realistically, it’s not going to happen overnight,” he said. “If it happens at all it’s going to happen in stages. But let’s get a plan in place and build the first stage. I can live with a plan that you’re working toward and funding as you go. But I have a hard time living with no plan at all.”

The Roanoke-Blacksburg Regional Airport and its terminal are “nice,” Fralin said, but reliable air service is an issue.

“We’ve got researchers flying out of here that are headed all over the world, and they can’t take a chance on a connecting flight from Roanoke to Charlotte or to Atlanta or to Philadelphia being canceled at the last minute,” he said.

“It happens all the time coming out of the Roanoke airport. It’s those kinds of things that get … to the vision of your leaders. And then also gets back to the population. We’re an odd-size population for major air service.”

FBRI and its Riverside Center siblings, the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine and the university’s Animal Cancer Care and Research Center, all feature research components. The school of medicine is set to grow.

The medical school recently announced plans to double its enrollment and expand into a new, 100,000-square-foot building by July 2028. This year’s state budget earmarks included $6.5 million to help with that expansion.

Fralin believes the complex will ultimately need even more room to expand.

Riverside Center is a great place that was well-designed, “but it is fast outgrowing that,” he said. “It’s got to have more land.”

Whatever the limitations in property and travel, the work coming out of FBRI is starting to get traction. Fralin said he is seeing a lot of the research developed at Riverside Center spinning out into startup companies.

Burcham, of the Roanoke Blacksburg Innovation Alliance, pointed to several companies with potential for success. Future clean room space denizens Tiny Cargo, Acomhal and Qentoros are among them.

BEAM Diagnostics, founded by Sarah Snider and the late Warren Bickel at FBRI, develops digital tools to screen for substance use disorder. Cairina Inc., a cancer-treatment startup centered on imaging, emerged from Jenny Munson’s lab at FBRI, Burcham said.

Meanwhile, a state-of-the-art cancer care center is scheduled to join the Carilion and Riverside Center neighborhood within the next three years. Cancer therapeutics and medical device manufacturers — the latter associated more closely with Virginia Tech Corporate Research Center — are the startup clusters growing most quickly in the region, she said.

“FBRI has just a dynamite lineup of faculty,” Burcham said. “And in my perspective, they’re hiring more and more faculty that are entrepreneurial and looking to start companies.”

Burcham’s Roanoke Blacksburg Innovation Alliance — with RBTC and Roanoke Accelerator Mentoring Program under its umbrella — is poised to help burgeoning businesses move beyond startup status, said Michael Friedlander, FBRI’s executive director.

All of the startups mentioned above went through the RAMP program over the past few years, and the Innovation Alliance is working to bring venture funding to bear.

“There’s this whole ecosystem that’s been developing in Roanoke for entrepreneurs, not just people here at our enterprise, but all kinds,” Friedlander said. “But we benefit from it too. We want to learn, get mentorship, be helped, start up companies and so forth.

“And, you know, they don’t all hit, and … not the majority of them hit, but you have enough starting, and you have enough successes, subset of that, you start to grow a … real enterprise in a community.”

Funding cuts loom

On the night of Feb. 7, a Friday, the National Institutes of Health issued a directive to slash previously negotiated funding for existing research projects and capped future funding for research.

The cuts in question were to so-called “indirect cost rates” — also called facility and administrative costs. Those include research laboratory maintenance, high-speed data processing, data storage and security, lab equipment, radiation safety, hazardous waste disposal and support staff for administrative and regulatory compliance work.

Indirect cost rates are different from direct costs, which fund the research itself.

Virginia Tech’s indirect cost rates were about 60% as recently as last year, according to university documents available publicly. Under that math, for every dollar granted for research, about 60 cents would be added for the indirect costs that support the research.

The NIH notice capping indirect costs at 15%, even for previously negotiated contracts, was due to go into effect Feb. 10, the following Monday.

Multiple states’ attorney general offices and lawyers for two academic groups — the Association of American Medical Colleges and the Association of American Universities — filed for a temporary restraining order against the NIH and its overseer agency, the Department of Health and Human Services. A federal judge in Massachusetts granted the request that day, pending a Feb. 21 hearing.

At FBRI, where most grants are multiyear awards, the NIH’s portfolio is $163 million, which accounts for about 68% of all outside funding to the research institute, according to the university. Other research at the university could be affected, as well, Virginia Tech President Tim Sands wrote in an open letter to the university community.

“Lives will be lost due to the corresponding reduction in the pace of biomedical research,” Sands wrote. “It will degrade the nation’s ability to compete in a global technology environment, threaten our national security, and impact the economies of the states and localities that host these institutions.”

After the Feb. 21 hearing, U.S. District Judge Angel Kelley ordered a preliminary injunction against the NIH and HHS.

The NIH notice “impacts thousands of existing grants, totaling billions of dollars across all 50 states — a unilateral change over a weekend, without regard for on-going research and clinical trials,” Kelley wrote in a memorandum and order filed on March 5.

Among the issues was the NIH’s assertion that capping indirect rate payments at 15% would bring its reimbursement rate closer to that of such private organizations as the Gates Foundation, which also funds biomedical research at U.S. universities. The NIH’s rate change notice, however, did not provide reasoning to back up that assertion, as the law requires in such moves, Kelley wrote.

“The Rate Change Notice seems to have ignored the need for indirect funds in the administration of any and all research,” she wrote. “In essence, by cutting indirect funds, NIH is cutting research. There also seems to be a limited rational connection between the facts, particularly the nature of private funding opportunities and their differences from federal funding grants, as well as the limitation on university endowments, and the decision to cut ICRs to bring them in line with private organizations.”

The judge, citing a declaration submitted to the court in the case, wrote that most universities’ existing endowments can’t be drawn down to cover research infrastructure costs.

“[E]ndowments, which vary from institution to institution, will be unable to make up the shortfall — a majority of the funds in endowments are legally bound for specific purposes based on the gift.”

Kelley’s ruling that the rate cut could cause “irreparable harm” to the institutions, their communities and far beyond set up an even more detailed hearing and a final decision that would stand, pending likely appeals from either side that could reach the Supreme Court.

Meanwhile, according to the judge’s memorandum and order, defendants “subsequently filed reports confirming that they would not implement the Rate Change Notice until further notice from the Court.” The payments have continued, a Virginia Tech spokesman said.

Foundations for the future

There’s a sense of limbo, but there’s a sense of traction that continues.

Part of that hinges on agreements the city made with private developers around the biotech corridor a decade ago, said Marc Nelson, Roanoke’s economic development director.

Richmond-based WVS Companies, working at that time with Roanoke developers Bern and Aaron Ewert, brought a major investment to The Bridges development. Then-city manager Chris Morrill and then-assistant city manager Brian Townsend, working with the city council and the city’s economic development authority, crafted a performance agreement with WVS that remains in place.

“We invested $2 million up front that helped kick start that entire project,” said Nelson, who came to the city shortly after the deal was signed and has been involved with it ever since.

The 12-year agreement committed the developers to put in public roads and utilities to municipal specifications, and build over the top of parking garages in that flood plain by the Roanoke River, among other requirements. The developers received 75% of their city taxes back each year.

Similar agreements are in place for the Spring Hill Suites building at Riverside Center and the Hampton Inn & Suites atop the city parking garage downtown, on Campbell Avenue.

“I would argue that the city’s use of such agreements … played just as large a role in shaping Roanoke as any private developer,” Nelson said in an email exchange.

Ultimately, it serves a public benefit, Nelson said.

“They’re going to put public roads and utilities in there, in an area [where] it is really needed,” he said in a recent interview. “They needed residences over there. They needed amenities for people to go and get coffee and have places to go have a drink and go to a restaurant.”

And it’s created a public space that looks good to outsiders. Among the connections that King, of Carilion Innovations, has made is with Andy Kant, director of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s medical technology incubator, FastTraCS. Kant has been to Roanoke several times over the past year. These were his first visits to Roanoke.

Kant said he was impressed by what he called the “heart of the innovation area.”

It’s still small, compared to the Research Triangle in North Carolina, but it looks like people are up to the challenge of making it work long term, he said.

”I will say they’re doing a pretty good job in terms of the support that they’re putting forth,” Kant said. “I feel like money is flowing for … early-stage startups. I went to some pitch event that they had held, which was pretty interesting.

“I think they’re doing a pretty good job of trying to build community out there … to get people excited, feel like they’re a part of a community and feel like you’re supported when you’re trying to do this kind of entrepreneurial work which sometimes feels pretty lonely, right? You’re kind of on an island sometimes.”

It’s the same potential that drew his Carilion counterpart to Roanoke, as it did FBRI’s Michael Friendlander going on 15 years ago.

“You know, we’re not Austin, Texas, we’re not Boston. We’re growing up, but we’re not nowhere,” Friedlander said. “Now we really have got some investment funds here, [VTC Ventures fund], and RAMP and Verge and all that are really helpful. So again, I can now actually point to those things. In the early days, we talked about [how] we’re going to have that someday.”

And with that can come crucial discoveries that happen inside a lab, or labs, that sprang from those old grounds that once held mills, scrap heaps — and nearby, a broken old railroad depot with a tree that grew through its collapsed roof.

Now the depot is restored and old grounds next door are repurposed, or on their way to new uses. A city that was struggling to redefine its identity a quarter-century ago stands strengthened by its continuing growth, ready to benefit from its new status.

Correction 1 p.m. March 11: Johnson & Johnson’s JLABS is not a partner in the incubator lab building coming to Roanoke.

Comments are closed.