The year 2026 marks the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Cardinal News has embarked on a three-year project to tell the little-known stories of Virginia’s role in the march to independence. This project is supported, in part, by a grant from the Virginia American Revolution 250 Commission. Find all our stories from this project on the Cardinal 250 page. You can sign up for our monthly newsletter:

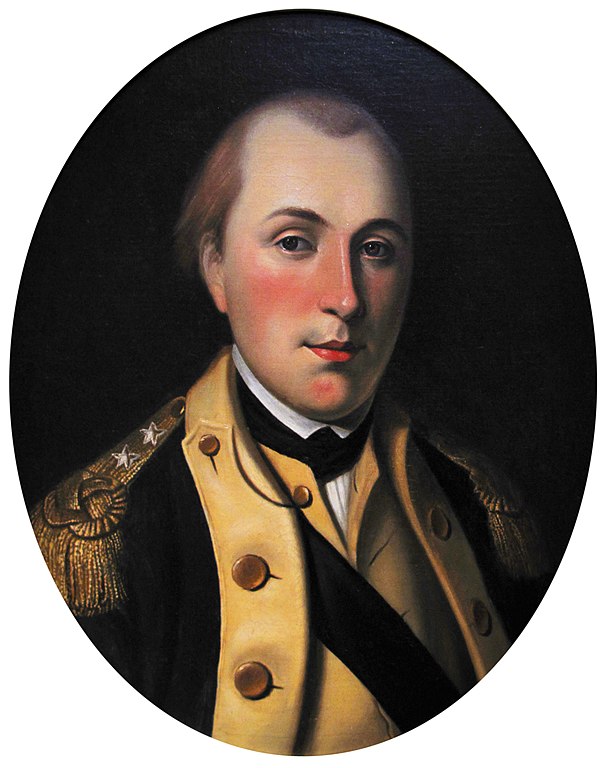

In November 1784, more than a year after the Treaty of Paris brought the Revolutionary War to a close, Marquis de Lafayette, a general who helped lead American forces to victory, wrote a note of reference on behalf of a man who played a critical role in the final days of the fighting.

This is to certify that the bearer by the name of James has done essential services to me while I had the honour to command in this state. His intelligences from the enemy’s camp were industriously collected and faithfully delivered. He perfectly acquitted himself with some important commissions I gave him and appears to me entitled to every reward his situation can admit of.

The revered French aristocrat was trying to rectify what he viewed as an injustice. James Lafayette had risked his life for American independence but could not redeem a promise of freedom.

James Lafayette was an enslaved Black man who lived in Virginia during the Revolutionary War. He spied for the Marquis de Lafayette at the 1781 Siege of Yorktown, crossing enemy lines, returning with vital intelligence. Yet Lafayette’s audacity was not enough to overcome a legal system that kept him enslaved, nor was it sufficient to secure his legacy in public memory as a Revolutionary War hero.

That is starting to change. In recent years, the story of Lafayette has begun to reemerge, thanks to historians devoted to showcasing the extraordinary bravery — and complex motivations — of ordinary Americans during the revolutionary period. In late March of this year, Lafayette will be honored with a statue in New Kent County where he lived, commending the life of a man whose courage helped steer the course of American independence, even as he lived in bondage.

The life of James Lafayette has been pieced together from relatively scant documentation, according to Stephen Seals, who portrays him at Colonial Williamsburg as a historical interpreter known as a Nation Builder. There was a reference to James Lafayette as a servant in the late 1770s, and Marquis de Lafayette’s mention to George Washington of an “honest friend,” along with his written testament of 1784. There are primary sources associated with his petition for freedom, which he finally secured in 1787. But then the record goes dark for a couple decades, Seals said.

James was born enslaved in 1748 on a plantation in New Kent County. As a child, he was the servant to William Armistead Jr., who was six years younger. LaVonne Allen, a New Kent County historian who is writing a biography of Lafayette, said that he became literate alongside Armistead when they were young. Like Armistead, Lafayette was likely tutored in English and French.

During the Revolutionary War, Armistead was in Williamsburg managing military supplies, with Lafayette alongside him as his servant. Existing records are not clear exactly how James Lafayette and the Marquis de Lafayette initially met, but this setting, late in the war, is the most plausible scenario.

By 1781, fighting had been dragging on for six years. The British army was holed up at Yorktown, waiting to be collected and evacuated by a naval fleet. Top brass on both sides of the conflict were seeking whatever advantage they could find. Spy craft was by then a well-established tool of the trade.

James Lafayette’s intelligence gathering provided crucial information. Behind enemy lines, Lafayette would have appeared to be a simple enslaved man, which might have allowed him to move about inconspicuously.

Lafayette’s 1786 petition for freedom hints at the nature of his subterfuge. He “found means to frequent the British Camp by which means he kept open a channel of the most useful communication to the army of the state,” the petition states. “That at different times your petitioner conveyed inclosures from the Marquiss in to the Enemies lines, of the most secret & important kind … ”.

Historians believe he acted as a double agent, feeding misinformation to the British. James Lafayette’s services — as the Marquis de Lafayette stated in his character reference — were essential, aiding victory in a campaign that ultimately convinced British policymakers that continuing the war was no longer worth it.

During this time, James Lafayette and the Marquis de Lafayette formed a close bond. Testament to this relationship is the name they shared. As an enslaved person, James Lafayette did not have a surname. The earliest reference to him, like virtually all enslaved people, simply calls him “James.” When he eventually obtained his freedom, there is no indication that he took the name of his enslaver, Armistead, although this name is sometimes associated with him. Instead, he wanted to honor the marquis and chose the surname Lafayette, which, late in his life, he may have shortened to Fayette.

The petition for Lafayette’s freedom also makes clear that he understood an undeniable fact about his actions: he was putting his life on the line. “The danger of that work was beyond the pale,” said Seals, the Colonial Williamsburg interpreter.

When Seals is explaining to others the choice Lafayette made, he uses the example of Major John André, a British intelligence officer who was known and respected by both sides in the war but who was nevertheless executed for spying. Lafayette would have understood that being caught would mean the end of his life, according to Seals. “To be a compromised spy is to die,” he said.

So, why did Lafayette make a choice with the potential for such grave consequences? Seals said that he is not entirely sure, but believes that Lafayette saw a path to freedom that allowed him to stay near his wife, Sylvia. Hundreds of Black Americans flocked to British lines after Dunmore’s Proclamation in 1775, which promised freedom to enslaved people who fought for the British. But that would have involved deploying to points unknown.

Lafayette, on the other hand, saw an opportunity close to home for “meritorious service” in the war — a requirement of enslaved soldiers on the American side to gain their freedom. An estimated 5,000 to 8,000 enslaved and free Black Americans fought for the Patriots during the war.

Even after helping clinch victory at Yorktown, however, a technicality — Lafayette had never enlisted in the armed forces even though he spied for the Americans — meant his request for freedom was initially denied. It was only after the Marquis de Lafayette interceded that James Lafayette became a free man in 1787.

That’s an injustice, said Allen, the New Kent historian. “He risked his life for this country and was forced to remain a slave for six years,” she said.

Allen’s home in New Kent has a tangible link to Lafayette. Her family’s property line touches land that once belonged to Lafayette. Two-and-a-half decades after he became a free man, Lafayette bought 40 acres in New Kent. As a free country farmer, he appears to have bought some enslaved people, but there is likely a benign explanation for these transactions, according to Seals.

“Most Black individuals were trying to free family,” Seals said. “Virginia made it hard. There were always hurdles to go over. Virginia law wouldn’t have let him free his children, but he could buy them, and they would be free when they became adults.”

There are a few clues that life as a free farmer provided no relaxed life for Lafayette. In 1818, he applied for and received a veteran’s pension. In 1824, as the Marquis de Lafayette returned to the United States for a 24-state tour, James Lafayette longed to see his old friend.

“James has expressed a great desire to see the Marquis at the approaching festival at Yorktown, but it is believed he is too poor to equip himself for the occasion without some aid,” reported the Richmond Compiler in 1824.

James Lafayette did manage to find needed funds to journey to meet with the Marquis de Lafayette when he arrived at Yorktown. A contemporary account says that the Frenchman called out to James Lafayette and embraced him. The gesture was both an unusual public display of interracial companionship and a sign of the enduring bond between the two men.

When James Lafayette died in 1830, he largely took the details of his life to the grave. Records that might have shed a little more light were lost, according to Allen. New Kent was one of Virginia’s so-called “burned counties,” as its courthouse and many of the records it contained went up in flames during the Civil War.

That hidden history is frustrating for Lafayette’s many descendants, who have spread out across North America. Carol LaFayette-Boyd is a retiree who lives in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. She is a descendant of James Lafayette but lacks all the documentation to definitively prove the lineage.

Although she maintains an intricate family tree with exhaustive explanations of members of previous generations, LaFayette-Boyd, like many Black people in North America, has relied on oral history and intuition to fill in the gaps. “I know in my heart and soul that he’s mine,” she said.

LaFayette-Boyd has been able to trace her lineage back to her great-great-grandfather in Norfolk in 1847. While there were murmurings among some family that there was an illustrious connection to the Revolutionary War, solid proof vanished through the years. The timeline nevertheless works out.

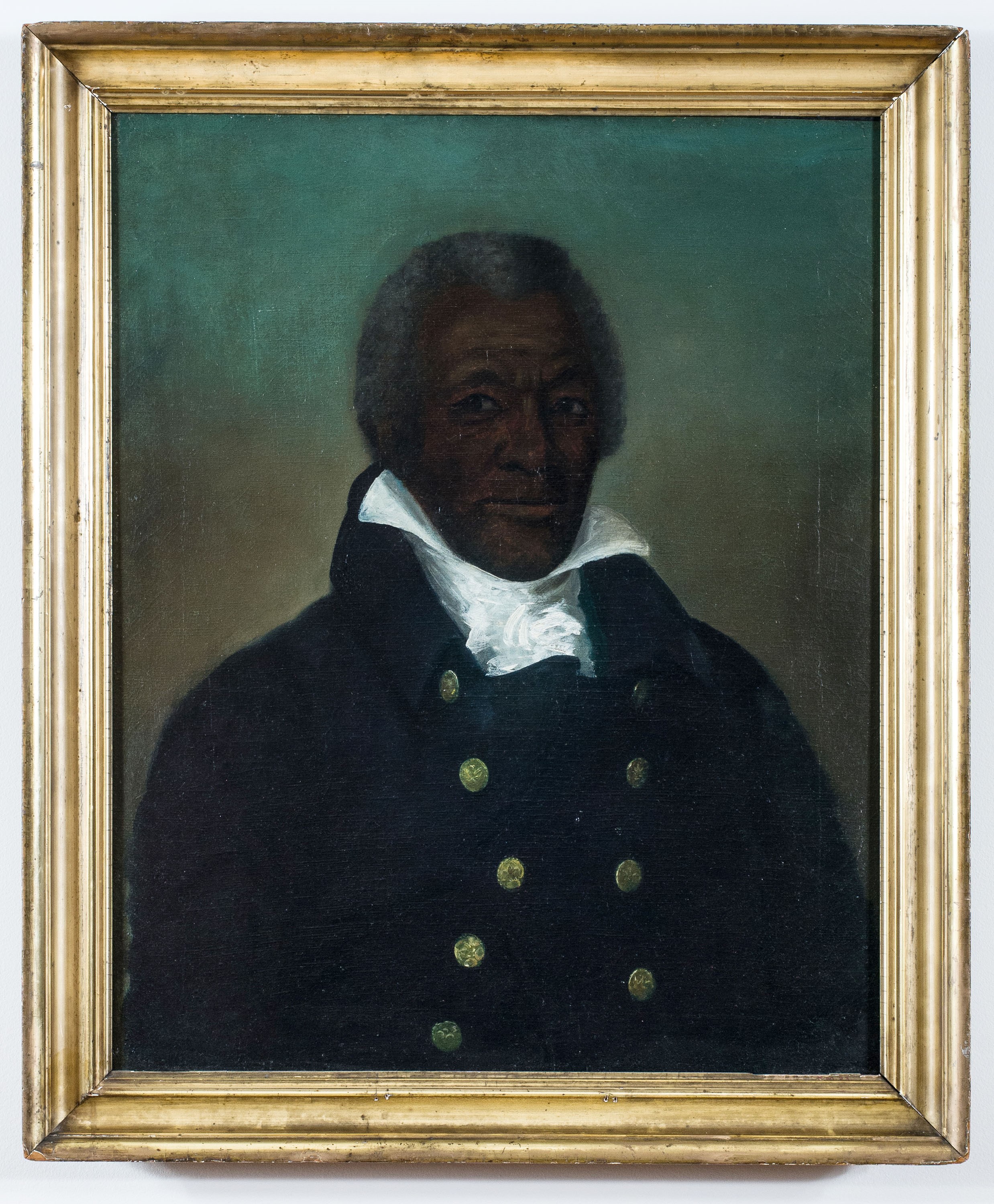

For LaFayette-Boyd, she remembers vividly the instant she knew that she was descended from James Lafayette. All it took was seeing the portrait of James Lafayette that another family historian shared. The resemblance to her father was uncanny. “I can remember sitting at my desk in my office on the 12th floor,” she said. “I’ll never forget the feeling of seeing that picture and thinking, ‘he’s mine.’”

LaFayette-Boyd is among a growing group of family members and historians who have helped Lafayette’s legacy blossom. There was a single portrait of Lafayette painted by John B. Martin in 1824, but his memory had been largely forgotten in the two centuries since.

In 2013, Seals started portraying James Lafayette at Colonial Williamsburg, helping to bring his story to light. And soon daylight will shine on Lafayette brighter than ever before. On March 29, the African American Heritage Society of New Kent, in partnership with the Virginia chapter of the Children of the American Revolution and its president Sarah Terpenning, will be unveiling a monument in Lafayette’s honor on the grounds of the historic New Kent County Courthouse.

Allen believes that this gesture of recognition is long overdue, but that now is better than never. “His accolades should have come 250 years ago,” she said. “This man is America’s hero.”