Sometime this week, maybe Wednesday, the U.S. Senate will vote on a resolution by Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Va., to block President Donald Trump’s tariffs on Canada.

Kaine might pick up enough Republican votes in the Senate for the resolution to pass — Sen. Rand Paul, R-Ky., a tariff opponent, has said there may be four Republicans uneasy enough about tariffs to join with Democrats on this vote.

“However,” Politico reported, “it’s likely the resolution never comes up in the House, where Speaker Mike Johnson moved earlier this month to block the ability of tariff critics to force a floor vote on ending the kind of national emergencies Trump is citing to levy the tariffs.”

That means what we’re witnessing is mostly symbolic: “Losing the vote,” Politico said, “would represent the most significant rebuke to Trump that congressional Republicans have yet mustered in his second term.”

It might be of interest to politically minded Virginians to see their junior senator being the one who leads the charge against the administration. However, it ought to be of interest to a broader swath of Virginians to understand just how tied our economy is with our neighbor to the north — and therefore how much we have at risk in any trade war.

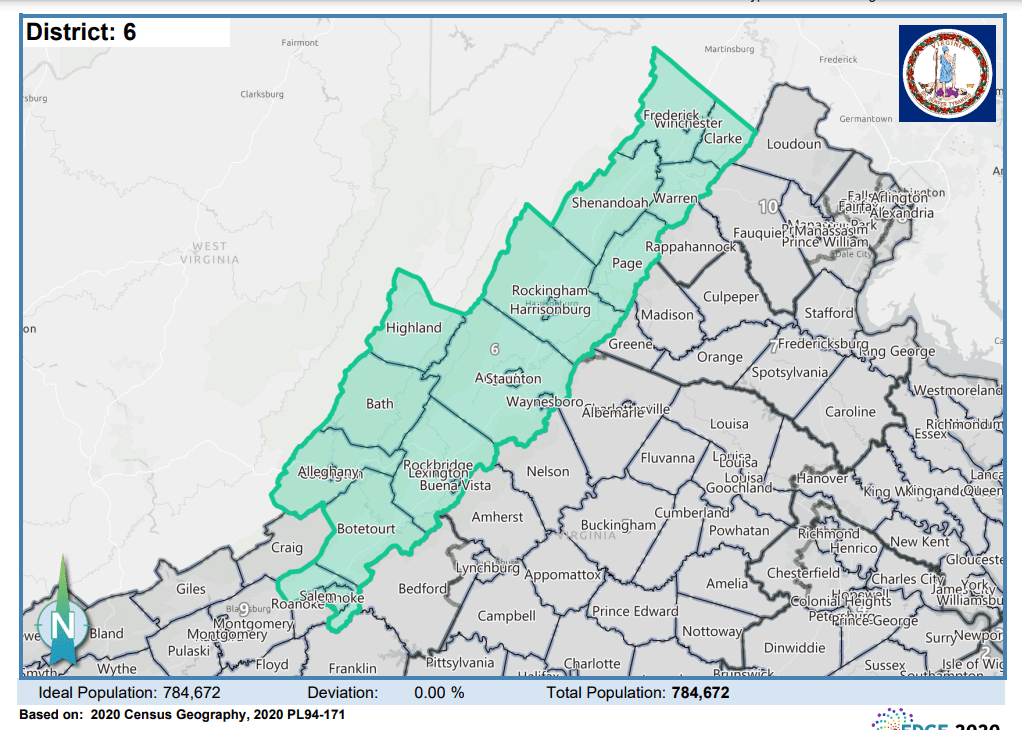

Spoiler alert: The parts of Virginia at most risk in a trade war with Canada are west of the Blue Ridge, specifically the 6th and 9th Congressional Districts, the two most Republican districts in the state, currently represented by Ben Cline and Morgan Griffith. Between them, those two districts have nearly 10,000 jobs and nearly $1.8 billion of goods tied to exports to Canada, according to an analysis of U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis data. If you factor in services that companies in those districts are selling north of the border, then the trade value rises to $2.69 billion in total Canadian exports from the western part of Virginia.

In politics, this is called “cross-pressure,” where members of Congress philosophically inclined to back the policies of a president from their own party might find themselves facing questions at home if that president’s trade war with Canada backfires. Any economic casualties might come first on poultry farms in the Shenandoah Valley or any of the auto parts manufacturers along Interstate 81.

Let’s dig deeper into this data.

Trump has famously said of Canada: “We don’t need anything they have.” The marketplace begs to differ or we wouldn’t have the trade deficit that Trump says he is concerned about. At the risk of getting lost in economic theory, it’s worth asking whether we need a trade surplus with every country. The whole point of trade is to acquire things that you can’t produce on your own, or can’t produce as cheaply. This is why we don’t mind importing coffee; we could grow the bean here in greenhouses, but the cost would be more than we’d want to pay.

The U.S. runs trade surpluses with some countries — the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis says our biggest is with the Netherlands, followed by all of Central and South America. Over on the deficit side, our biggest trade deficit is with China. We buy $295.4 billion more from China than China buys from us. There’s broad consensus across the political spectrum that this is a problem, but consumers like inexpensive goods, even if they’re made by poorly paid workers in foreign sweatshops. Our 10th-biggest trade deficit is with Canada, behind even Ireland, which might make you wonder why we’re more upset with Ottawa than Dublin.

Trump has said that his goal is to get Canada to crack down on fentanyl being smuggled into the U.S., but the vast majority of fentanyl comes into the country through Mexico. According to U.S. Customs and Border Protection, so far this year 1,580 pounds of the deadly drug have been seized along the Mexican border, 49 pounds at “interior” points of entry and 1 pound along the Canadian border. Of course, you never know what’s not being seized or where, but these numbers would suggest that there’s 49 times more smuggling through American airports than along the Canadian border. It’s not as if the Canadians are the only ones doing border checks; we’ve got agents there, too, and they’re not finding the stuff, either.

The reason there’s been such political pushback against U.S. tariffs on Canadian imports is the very real fear of retaliatory tariffs from Canada on American products — and the reason that matters is that the two nation’s economies are closely integrated. That’s a product both of geography and of more than a century and a half of warm relations that Trump is now busy undoing.

Canada is an easy country to ignore for the same reason that it’s so important to us: It’s nearby, it’s politically stable and it isn’t particularly exotic unless you’re in French-speaking Quebec, in which case you might well be in France. Economically, though, we are more dependent on Canada than we realize.

For 23 states, Canada is that state’s top import market, and some states are highly dependent on Canadian goods, according to data compiled by Visual Capitalist. In Montana, 86% of the state’s imports come across the northern border. In North Dakota, 75%. Even next door to us in West Virginia, 40% of imports come from Canada — more than even China. Those are the states that will first feel the bite of tariffs, a fancy word for taxes. Virginia will be one of the last. I’ve not found a figure I trust for what percentage of our imports come from Canada, but state figures say we import more from China than anywhere else and Visual Capitalist puts that figure at 13%. Canada ranks third for us, behind Mexico.

Where Virginia — and many other states — are most vulnerable in a trade war is with retaliatory tariffs on U.S. exports to Canada. In business terms, Canada is our best customer. Canada buys more from the United States than any other country does. If anything disturbs that relationship, some American jobs will be at risk. Tariffs risk disturbing that relationship.

For 32 states, Canada is their top export market. Virginia is one of those 32. Last year, Virginia sold $3.4 billion worth of products to Canada — 15% of our total exports — according to the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative. China ranked a distant second at $1.5 billion, India third at $1.4 billion. Those two countries combined still didn’t add up to what the Canadian market means to the Virginia economy.

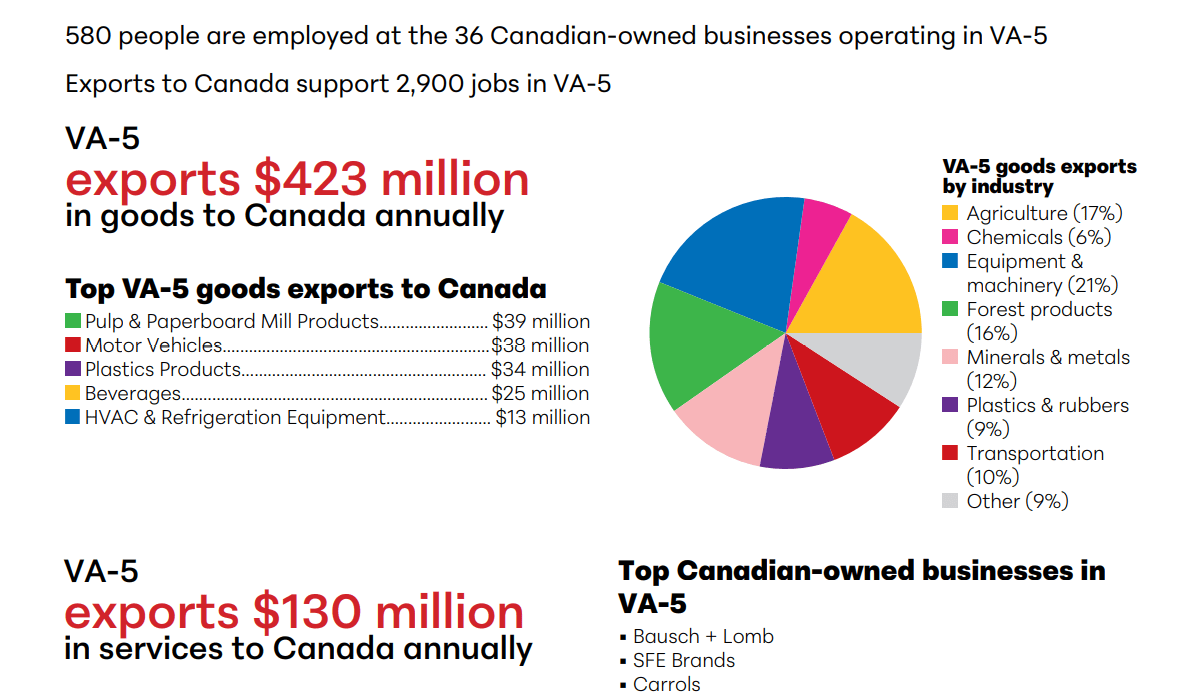

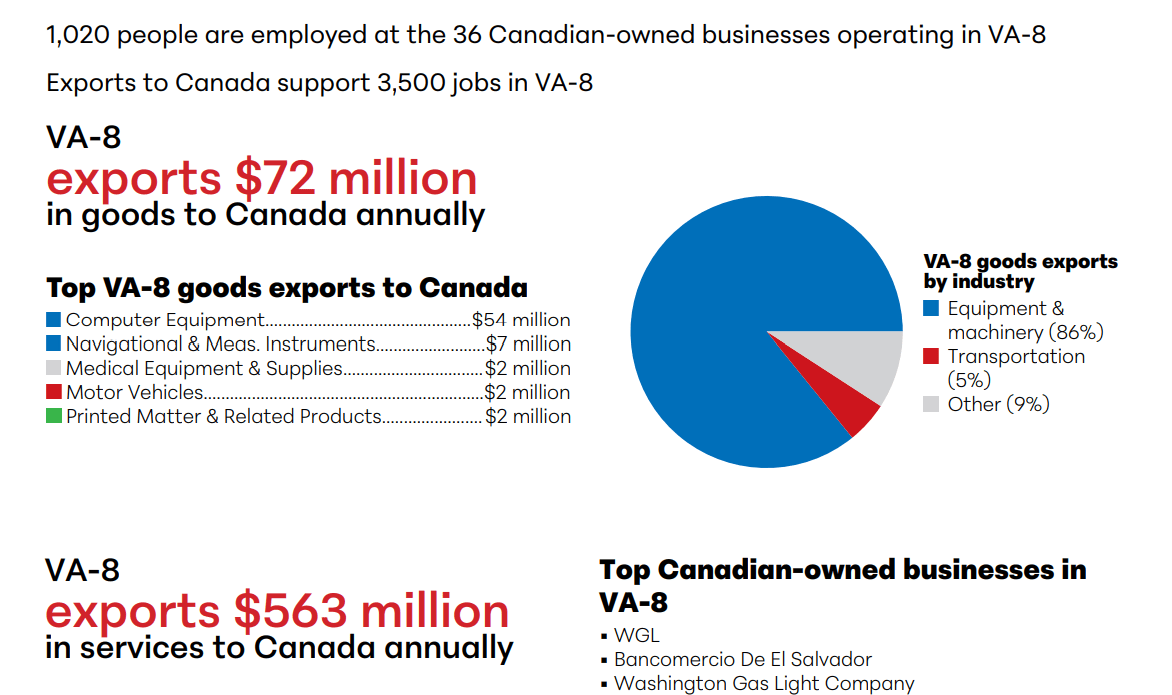

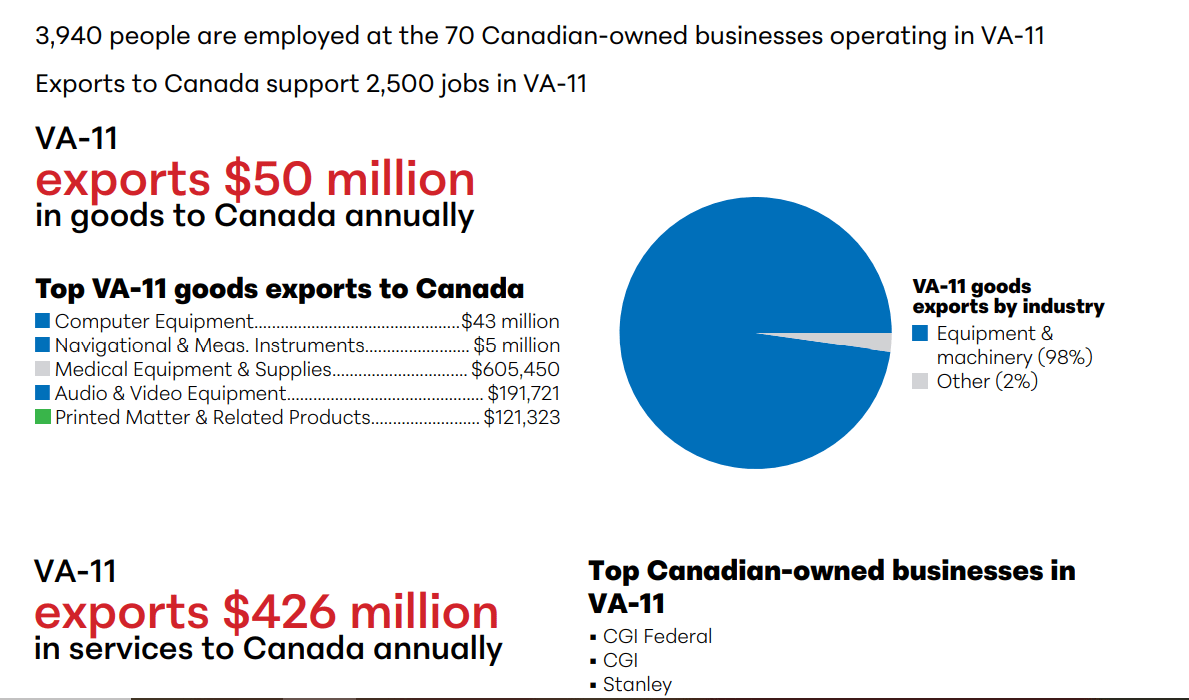

All those numbers may be a blur, but let’s make them more specific. The Canadian embassy in Washington took employment statistics from the U.S. government and has produced an economic profile of each congressional district in the country. This is the extent of Canadian propaganda: publishing the American government’s own numbers. (They are a wily bunch indeed.)

Here’s what we find. These are the number of jobs tied to exports to Canada in each of Virginia’s congressional districts: District (ranked by jobs) Jobs tied to exports to Canada General geography of district Representative 6th 5,350 Roanoke Valley, Shenandoah Valley Ben Cline (R) 9th 4,200 Southwest Virginia Morgan Griffith (R) 8th 3,500 Northern Virginia Don Beyer (D) 5th 2,900 Southside, Lynchburg, Charlottesville John McGuire (R) 11th 2,500 Northern Virginia Gerry Connolly (D) 4th 2,400 Richmond, eastern Southside Jennifer McClellan (D) 10th 2,350 Northern Virginia Suhas Subramanyam (D) 3rd 2,050 Hampton Roads Bobby Scott (D) 1st 1,750 Eastern Virginia, part of Richmond suburbs Rob Wittman (R) 2nd 1,700 Hampton Roads Jen Kiggans (R) 7th 1,150 Piedmont, part of Northern Virginia Eugene Vindman (D)

Why do the 6th and 9th districts rank so high? Auto-related jobs. There’s a cluster of auto-related jobs along the I-81 corridor, with the Volvo truck plant in Pulaski County being perhaps the best known but by no means the only one. (You can see a list of auto-related companies in Virginia on page 3 of this state report). The 6th District gets bumped higher on the list by the poultry industry in the Shenandoah Valley and also the forest products industry, such as the WestRock paper mill in Covington. You scroll through all this data, district by district, but you’ll see that 25% of the exports in the 6th District are tied to the auto industry. 44% of those in the 9th District.

Sources: Trade Partnership: Goods exports (2024 data, 2/2025 release), services exports (2023 data, 12/2024 release) and jobs, calculated figures, based on U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis data at state and national levels. Dun & Bradstreet:

Canadian-owned businesses (2/2025 release). Figures may not add up due to rounding.

This is where political desire collides with economic reality. Trump doesn’t want Americans buying cars that were assembled in Canada. “I’d rather make ’em in Detroit,” he’s said. He says 20% of the cars sold in the U.S. come from Canada; but Cars.com says the figure appears to actually be 4.2%. Whatever the number, Trump’s point is he wants to boost American manufacturing — a worthy goal.

The challenge is that the auto industry has, for better or worse, evolved a supply chain that routinely crosses international borders. NBC recently reported: “There’s no such thing as a fully American-made car.” Such reports usually focus on how many foreign-made parts go into an American-assembled vehicle, but the industry is really much more complicated than that. We also have a lot of American-made parts going to Canada to be assembled into vehicles.

Yes, it might be better if those were American-made parts going to U.S. auto plants, but the current system is not going to be unwound quickly — if it all. Corporate America thinks both short-term (quarterly dividends) and long-term — and that long-term horizon extends longer than a president’s term. In the meantime, parts crossing the border are going to get taxed and automakers will either need to eat those costs or pass them onto consumers. You can consult your own experience to decide which is more likely.

It’s also not so simple as a single part being shipped from one country to another and staying there. The London Free Press — that’s London, Ontario, by the way — recently reported about a scrap metal company in Ontario that is part of the auto parts supply chain: “Scrap from Linamar Corp. crosses Canada, U.S., Mexico borders 7 times until it becomes an automatic transmission that powers a vehicle,” the paper reported. That’s also not unusual.

That paper quoted Flavio Volpe, chief executive of the Automotive Parts Manufacturers Association: Until now, “No one cared if an auto part crossed the borders six or seven times. That is, not until we have a crisis like this. … We have highly integrated post-industrial powers that have grown together.” Now the leader of one of those powers is trying to pull it apart and the pain will be felt on both sides of the border, from the Linamar scrapyard in Gueph, Ontario, to, perhaps, auto parts companies along I-81.

Other products have their own economic ecosystem. The U.S. Department of Agriculture says that 80% of the chicken meat consumed in Canada comes from the United States. If Canada’s retaliatory tariffs on U.S. poultry makes American chicken too expensive for Canadian consumers — or if Canadians decide simply not to buy American in the same way that some Americans try to avoid buying Chinese — then there’s a market opportunity for other countries. In a report last fall, before these tariffs were on the table, the USDA warned that “Chile [has] emerged as a significant supplier, and is expected to gain additional market share in 2025.” Canada’s retaliatory tariffs could hurt farmers in the Shenandoah Valley and benefit those in South America.

The bottom line: Farmers and factory workers in the western part of Virginia are now on the front lines of a trade war.

Endorsements and more endorsements

The campaign season is already upon us, first of all in June primaries. I’ll have a roundup of endorsements in this week’s edition of West of the Capital, our weekly politial newsletter. If you’re a campaign I haven’t heard from yet, and have endorsements to share, send ’em my way at dwayne@cardinalnews.org. For those of you who aren’t signed up for the newsletter, you can do so here: