Want more on Virginia’s population trends? We’ve collected all our demographic coverage in one place.

Martinsville recently moved past Lynchburg in the category of dysfunctional city councils when a deputy forcibly removed a city council member from a meeting after he began criticizing how a possible pay increase for the city manager is being handled. (See this story by Cardinal’s Dean-Paul Stephens and this follow-up.)

Who ordered the removal of council member Aaron Rawls is still in dispute, but that’s not the subject of today’s column. Instead, my curiosity is piqued by one of the many comments posted on social media about the story. One of the commenters offered a lengthy critique of Martinsville’s government and then observed: “Martinsville is a dying town.”

Opinions may vary about who’s right and who’s wrong in the council dispute, but the suggestion that Martinsville is dying strikes me as something that can be determined through objective measurements. I’m not a doctor, but I once portrayed one in the play “The Spiral Staircase” back at Montevideo High School in Rockingham County, so allow me to take out my civic stethoscope and see how the patient is doing.

Before we take some readings, let’s first agree on what would constitute a dying community. “Dying” is a strong term when used to talk about a community. There are ghost towns where communities have truly died — we once ran a story about the once-bustling community of Cedar Grove in Rockbridge County, which is now simply gone, evaporated into history. There are certainly lots of places, though, that still exist but might be considered in poor health. Is Martinsville among them?

I’d suggest three easy metrics to look at: population, age and jobs.

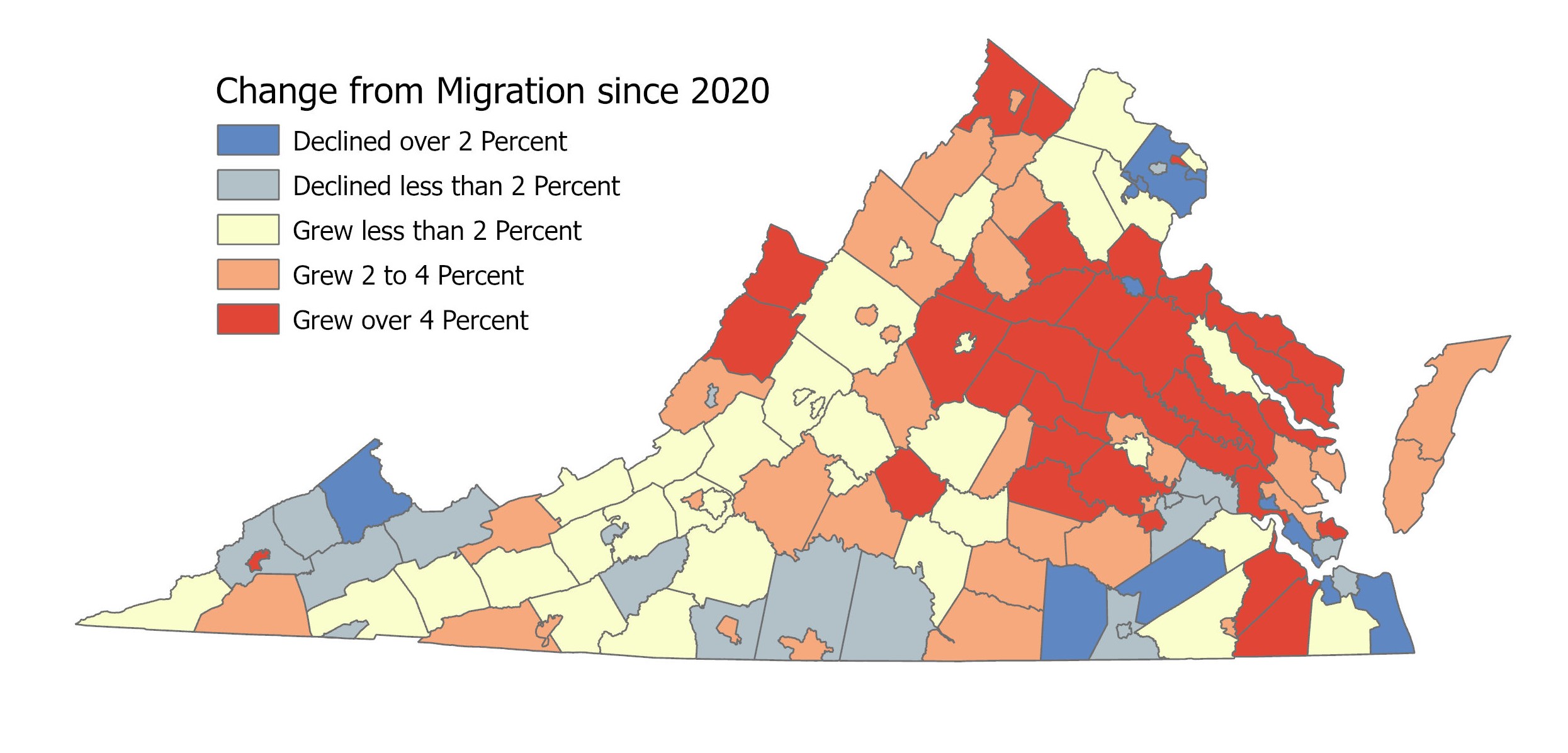

Population: The question isn’t simply whether a community is losing population, but whether it’s losing population through more people moving out than moving in. Many localities in Virginia are losing population, but they’re losing it because they have older populations and deaths exceed both births and net-migration trends. Roanoke is one of those, but we certainly don’t think of Roanoke as dying. Every year, more people “vote with their feet,” as Ronald Reagan liked to say, to move into Roanoke than move out.

Age: Is a community growing older or younger? The reality is that most localities in the country are growing older — some of that reflects a declining birth rate so everything is skewed older — so the better question might be a community’s relative ranking compared to other communities.

Jobs: Is the number of jobs growing or shrinking?

There are lots of other measurements we can cite, but these seem the basic ones — akin to heart rate, blood pressure and body mass index. So, on that scale, how is Martinsville doing?

Martinsville has more people moving in than moving out

We can start out by saying that Martinsville certainly isn’t dead. The latest population figures from the Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service at the University of Virginia show that since the 2020 census, Martinsville has lost population. However, it’s only lost population because deaths outnumber births and everything else. Over the past four years, Martinsville has seen 355 more people move in than move out, so something must be drawing people there.

To put this net in-migration in context, Roanoke’s net in-migration during that same period was 391 people — so Martinsville and Roanoke have roughly the same net in-migration, even though Roanoke is 7.5 times bigger. Martinsville had more net in-migration than Arlington, which saw 347 more people move in than move out. In fact, localities in most of Northern Virginia are now seeing net out-migration, so Martinsville is faring better than any of them by this metric.

Whatever problems Martinsville might have, people moving out isn’t one of them. Since Cardinal added a reporter in Martinsville, that reporter has written about multiple new housing developments in the city, such as the conversion of a former BB&T bank building and a former Winn-Dixie grocery into housing. The marketplace does not lie: The market sees opportunity in Martinsville because of that net in-migration.

Yes, Martinsville’s population today is down 32.4% from its high of 19,653 in 1970 — that’s a huge decline and definitely not a sign of good health. However, these more recent readings on net in-migration suggest that Martinsville is now starting to recover (and recover pretty nicely) after decades of economic trauma brought about by the collapse of its main industries.

While my focus here has been Martinsville, the city, because that’s where the council incident happened, we also need to talk about surrounding Henry County. They may be legally separate entities, but their economies are intertwined. Generally speaking, all the trends we see in Martinsville are replicated in Henry County; only the precise numbers differ. One small exception: Henry County is still seeing more people move out than move in. From 2020 to 2024, Henry County had 301 more people move out than move in. However, if you combine Martinsville and Henry County together, the region overall still had net in-migration — just on a smaller level. Furthermore, Henry County’s net out-migration is in the process of reversing. From 2000 to 2022, Henry County saw 1,142 more people move out than move in. By 2024, though, that had dropped to just 301. That’s because from 2022 to 2024, Henry County saw net in-migration, enough to reverse most of what it lost in the first two years of this decade. Henry County’s trends are in the right direction. Something is causing that to happen. People do not move into a dying community. They move out.

Martinsville is growing younger at a faster rate than all but one other community in Virginia

This might be the most amazing statistic of all. First of all, we can't really call Martinsville an older community because its median age is younger than Virginia as a whole — 37.0 in Martinsville to 38.8 statewide. Martinsville's median age also makes it younger than Roanoke at 38.6 or Salem and Danville at 40.2. If you want to look at what is statistically an older community, look at Fairfax County. At 39.4, it's older than the state's median.

Here's the mind-blowing stat: Martinsville is getting younger. Its median age has fallen from 39.7 to 37.0. Only one other place in Virginia has seen its median age fall at a faster rate — the city of Franklin.

The reason for Martinsville's drop in median age is a literal youth movement — a surge of people under 25 moving into the city. Here's what I wrote in a column last year:

Martinsville has a genuine youth movement going on. Here’s how dramatic that has been. Martinsville has added more people under 25 than Chesapeake, which added 294 but is otherwise one of the faster-growing localities in the state. Martinsville has also added more than the college town of Harrisonburg (388) and almost as many as Lynchburg (496), a multi-college town. West of that ring of growth around Richmond, and south of Interstate 64, Lynchburg and Martinsville — in that order — have seen the most net growth in residents under 25. Lynchburg isn’t that surprising, given all of its colleges, but Martinsville, which doesn’t have a single four-year college, sure is.

Statistically, Martinsville isn't dying. It's literally growing younger at a time when society as a whole is growing older. That's a pretty remarkable feat.

Martinsville's job growth hasn't recovered very much after a massive drop

Here's the vital statistic where Martinsville fares the worst: jobs.

The Federal Reserve has job stats that go back to 1990. Those show that employment in Martinsville peaked in June 1990 at 7,576. Those numbers fell throughout the 1990s and then dropped to 5,851 in December 1999 when Tultex abruptly closed. After a brief revival, they continued falling until they hit a new low of 4,704 in September 2016.

This is a direct consequence of the demise of domestic textile and furniture production, two of Martinsville's staple industries. Roanoke author Beth Macy wrote about this in her book “Factory Man.” (She's on our journalism advisory board, but board members have no say in news decisions; see our policy.) State Sen. Bill Stanley, R-Franklin County, often delivers a fire-breathing speech about government decisions on trade undermining the economy of all of Southwest and Southside. Things may be a bit more complicated than that, but, in basic terms, he's not wrong. Martinsville is a classic example of a Southern mill town left behind by a changing economy.

Today, Martinsville's employment stands at 5,872. That's the highest it's been since December 2001. (If you match up the dates and numbers above with elections, you'll get a better sense of why much of Southside has realigned politically.) Martinsville's employment base certainly isn't what it used to be. Its economic recovery is incomplete, but the recent lines are headed in the right direction.

Martinsville also has an unusual number of people who work outside the city. The U.S. Census Bureau says 38.3% of Virginians work outside the county or city where they live. In Martinsville, the figure is 49.9%. (See these numbers on the Virginia Public Access Project site.)

I know Martinsville hates to be compared with Danville, but this seems a useful comparison because both cities underwent an economic collapse at the same time. Danville has, over a quarter-century, reinvented its economy. Martinsville is still working on that. In Danville, 19.3% of workers commute outside the city. Martinsville's percentage is almost double that.

From the population figures, we can see that people clearly want to live in Martinsville — but they work somewhere else, probably because they have to. Martinsville's percentage of workers commuting outside the city is high for a Virginia city, but there are places with much higher rates — Petersburg has 65.3% of its workers who commute to jobs somewhere else. While Martinsville's figure is high, what's more noticeable is how low Danville's figure is. No other Virginia city has a rate of out-commuting that low.

Martinsville also has some of the lowest weekly wages in the state, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics: $826, compared to a national average of $1,394. Arlington comes in first in the state at $2,234. Here is where Martinsville fares the worst, and where Stanley's historical critique is most powerful. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, people in Martinsville in 1959 had a slightly higher income than those in Richmond and Roanoke, and distinctly higher than those in Norfolk and Portsmouth. Their incomes were higher than Charlottesville and Danville. In fact, their incomes were higher than most places in Virginia outside the Washington suburbs, which then were much smaller. You can see from the chart above that that's no longer the case. Those localities have been transformed by the new economy; Martinsville has seen its old economy collapse and must now be rebuilt. This has been a painful process, and that pain has not completely gone away. One hopeful sign: Wages in Martinville are now rising at a faster rate than anywhere else in the state, according to the U.S. Census Bureau (or at least they were from 2019 to 2022, the period covered in that study).

My conclusion, based on these vitals: Martinsville's population trends are quite healthy, but the city needs to create more jobs — and more better-paying jobs. That's also not a particularly unusual prescription.

Martinsville may have some economic health challenges, but it's definitely not dying. Perceptions, though, are hard to shake. As a species, we tend to remember the big, dramatic things (the collapse of textiles and furniture) but have a harder time recognizing slower, less visible change (the population changes I just described). We also remember the past and sometimes have a hard time visualizing the future. Roanoke spent decades regretting that it was no longer a railroad headquarters town but didn't really start making progress until it figured out what it could be instead. (See our Tech Town! series by technology reporter Tad Dickens.) Danville went through the same thing Martinsville did and is now recognized as a textbook example of a civic rebound (even before the casino). Martinsville probably was dying after the economic jolts of the 1990s and early 2000s. However, it's turned that around. Maybe not enough, but some, to be sure.

To change the mistaken impression that Martinsville is dying, the city simply needs more examples of those kinds of positive changes that it can point to — buildings being refurbished for housing, new employers being announced. Unfortunately, much of the news out of Martinsville is dominated by its leaders fighting — the squabble between the New College Institute and its former fundraising foundation, now a council member being escorted out of a council meeting. From where I sit, it's hard to tell who's right and who's wrong, and it may not really matter. What matters is for Martinsville's leadership to present an image that's more in keeping with the demographic facts on the ground.

The campaign season is already upon us, first of all in June primaries. I'll have a roundup in this week's edition of West of the Capital, our weekly political newsletter. If you're a campaign I haven't heard from yet, and have endorsements to share, send 'em my way at dwayne@cardinalnews.org. For those of you who aren't signed up for the newsletter, you can do so here: