Northern Virginia is home to 35% of the world’s data centers. These massive warehouse-like buildings house computers and networking equipment that store and send data — and feed our ever-growing demand for apps, artificial intelligence and cloud storage.

Now they’re coming to Southside.

They bring with them concerns about viewsheds, traffic, noise and energy capacity — but also the potential for transformational tax revenue and job creation.

Cardinal News reporters Grace Mamon and Tad Dickens talked with local officials, residents, energy providers, environmental experts and others about what communities in our region can expect as these developments spread southward.

Read all of our coverage:

Tax revenue from data centers can dramatically lower taxes for property owners, as in Loudoun County, or help pay for school renovations, as in Mecklenburg County. Economic benefits, including an influx of new money, are often the main reason that localities approve data center projects.

As the industry looks to expand outside of Northern Virginia, which has more data centers than anywhere in the world, it’s possible that Southside could reap some of these economic benefits.

Data centers are large, warehouse-like buildings that house computers and networking equipment used to store and send data.

A data center campus proposal in Pittsylvania County could generate “up to $100 million annually” in tax revenue, according to its developer, and create up to 240 jobs. At the end of its 10- to 15-year buildout, the project could represent a $3.7 billion investment.

The county budget for the 2025 fiscal year is about $239 million.

This is the second data center proposal Pittsylvania has seen — the first came in June 2024 and was approved unanimously by the board of supervisors. Construction could begin as early as mid-2025 or early 2026.

It’s hard to nail down exact figures for tax revenue and job creation at the outset of a project because the sizes of buildings and campuses vary, said Claire Bencks, spokesperson for the Data Center Coalition, the membership association for the data center industry.

It’s unclear how the economic benefits from data centers seen in Northern Virginia could translate to the southern part of the state. But Southside officials can look to other localities to see the benefits they’ve experienced.

Loudoun County has lowered its real estate tax rate incrementally over the course of several years by a total of 42 cents, saving the average homeowner about $3,000 annually, said economic development director Buddy Rizer.

In Mecklenburg County, home to the only data center in Southside, tax revenue collected from the Microsoft facility over the 14 years since it’s been operational helped fund a $154 million project to renovate a high school and middle school complex.

Still, some Pittsylvania residents say they’re skeptical of the figures provided by Balico, the Herndon-based company behind the data center project proposal.

They especially question the number of jobs and their estimated salaries, since localities with lots of data centers have had differing experiences with data center job creation.

Tom Gordy, a member of the board of supervisors in Prince William County, said data centers generate most jobs during the construction phase. After that, the servers inside the buildings run on their own, with little need for maintenance or repairs.

“When you talk about generally growing your economy [through data centers], just understand that what you’re getting is tax revenue and not a lot of jobs,” said Gordy, whose county has 10 million square feet of data center space operational, with plans for 90 million square feet total.

But job creation has been a main reason that the Fredericksburg area, just south of Prince William, has been working to attract data center projects for about a decade.

“Tax revenue is an important component, but in our case, it’s also about the jobs and the types of jobs,” said Curry Roberts, president of the Fredericksburg Regional Alliance, an economic development group.

A recent report by the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission found that the data center industry contributes about 74,000 jobs to Virginia’s economy annually.

The proposed data center project in Pittsylvania will go to a final vote by the board of supervisors on Tuesday; the planning commission in January recommended that the board deny the request. The campus would encompass about 740 acres in the county and include 12 data center buildings, each covering 396,000 square feet.

This is a scaled-back version of Balico’s initial proposal, which involved 2,200 acres and 84 data center buildings.

Steven Gould, the local attorney for Balico, said that the company hopes to eventually pursue the larger project and that the current proposal is just an initial phase.

Communities reap millions in tax revenues from servers

The tax revenue generated by data center projects can be particularly attractive to regions that are working toward economic growth, like the Danville-Pittsylvania area.

Loudoun County is anticipating between $800 million and $1 billion in tax revenue solely from the data center industry this year. This revenue comes primarily from a tax on the servers and other equipment housed in data centers

The county has about 50 million square feet of data center space operational.

“For every $1 that we spend in services to a data center, they provide $26 back in revenue, which is a figure that no other commercial industry can come close to providing,” Rizer said.

Prince William County has seen tax revenue from data centers to the tune of about $166 million during the past fiscal year. Most of the county’s data center-related revenue goes into the general fund, which primarily pays for education.

But the county recently reduced the real estate property tax rate from 96 cents per $100 to 92 cents per $100, Gordy said, after it raised its tax on computers and related equipment from $2.15 to $3.70 per $100 of assessed value, the highest allowed by local ordinance.

In Mecklenburg County, data centers pay 66 cents per $100 of valuation on computer and peripheral equipment.

Pittsylvania does not have a computer and peripherals tax rate that would pertain to data center equipment, according to the commissioner of revenue, Robin Goard. The county plans to tax future data center equipment at the personal property tax rate of $9 per $100 of valuation — a much higher rate than Northern Virginia localities.

Robert Tucker, chairman of the board of supervisors, declined to comment on whether the county is considering implementing a computer and peripherals tax.

Pittsylvania County’s tax rate has apparently not scared away data center developers, as the county remains a target for new data center projects.

Nor have increasing tax rates on data center equipment deterred developers in Northern Virginia, said Deshundra Jefferson, chair of the board of supervisors in Prince William.

“People were warning us that we were going to choke data center growth, that we were being greedy,” Jefferson said. “I’m telling you, no one left because we raised the tax and we still have applications coming.”

Jefferson recommended that other localities do this as well, and especially advised against lowering this tax to entice data center development.

“Don’t offer tax incentives if you don’t have to, and I don’t ever think you have to,” she said. “I don’t want localities to fall for that. … Data centers are going to come because they need land.”

Of the $166 million in tax revenue derived from data centers in Prince William, about $66 million was from the computer and peripheral tax. Last year, 96% of computer and peripheral tax revenue in Prince William was generated by data centers alone, according to a report from the county’s financial department.

Prince William expects to see about $55 million in additional revenue from data centers after raising this tax.

As communities consider development proposals, Bill Wright, a Prince William County resident and vocal opponent of data centers, cautioned that the tax revenues promised by developers don’t always materialize.

He cited the Prince William Digital Gateway project. When developers QTS and Compass Datacenters presented the plan to the county, they promised $700 million in annual tax revenues. By the time the project came before the board of supervisors, the tax revenue was about half the initial figure, said Elena Schlossberg with the Coalition to Protect Prince William County, a grassroots organization that opposes data center growth.

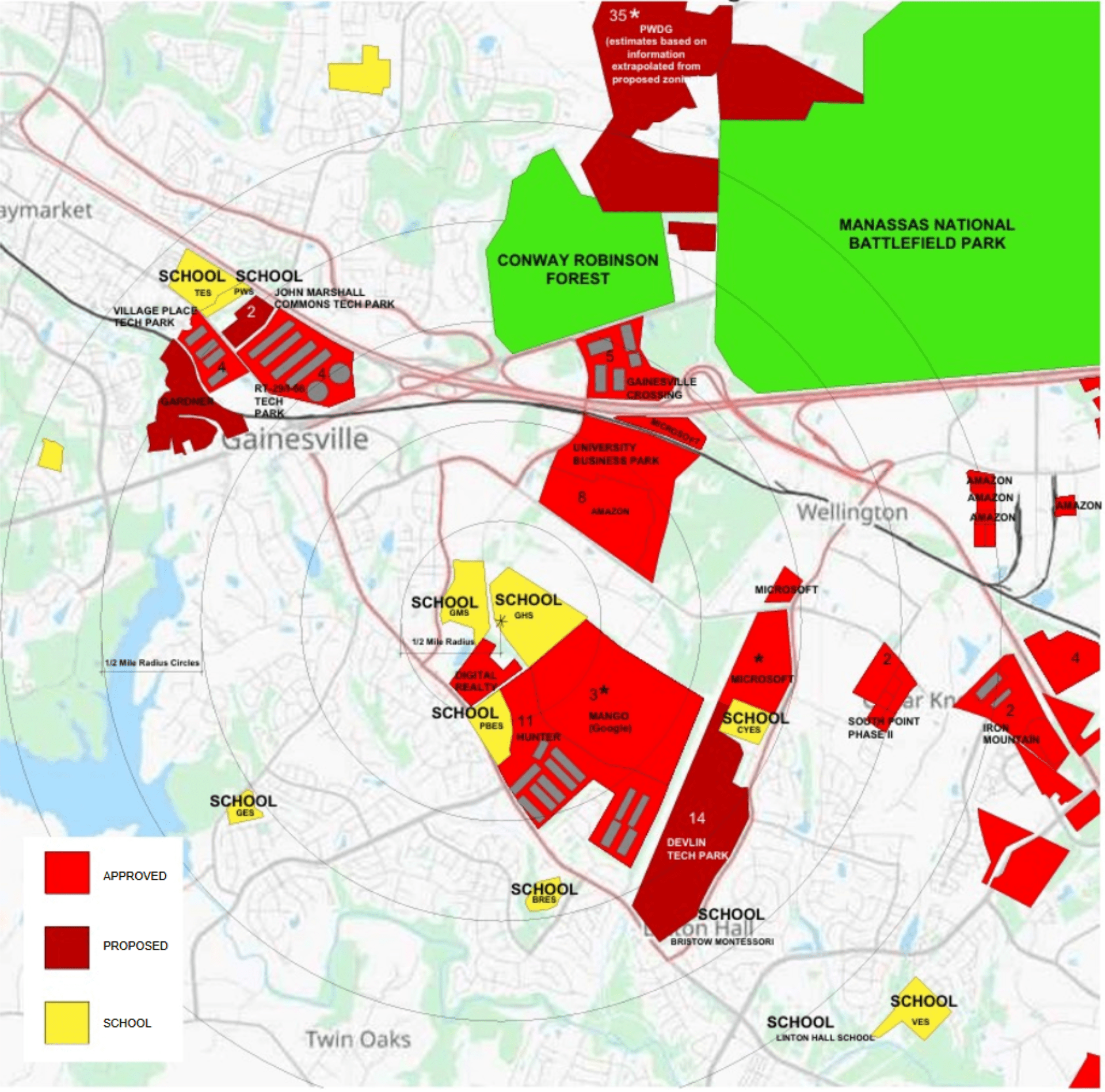

The project is currently tied up in lawsuits brought by neighbors. If it comes to fruition, the campus would encompass over 2,100 acres in a more rural part of the county, becoming the largest data center project in the world with 23 million square feet of data center space.

Job numbers vary greatly

Outside of construction, most data center jobs are custodial and security-related, Gordy said.

“There’s a few people in there that are monitoring and working on servers, but data centers utilize remote management,” he said. “That’s a practice that, in the last year or so, became a trend in cost-cutting for data centers.”

That’s why, even though Virginia has more data centers than the rest of the world, it does not have the most data center employees. Out-of-state data center employees working remotely on Virginia data centers do not count toward Virginia’s employment figures.

More than 40% of U.S. data center employees are in five other states: California, Texas, Florida, New York and Georgia, according to a U.S. Census Bureau report.

According to the same report, data center employment is also growing, increasing by 60% between 2016 and 2023.

The JLARC report found that 250,000 square feet of data center space might have about 50 full-time workers, about half of whom are contract workers.

Construction of a single data center building usually takes between 12 and 18 months, according to the study, and “data center representatives indicated that, at the height of construction, approximately 1,500 workers are on site from various construction-related industries.”

According to the report, the data center industry contributes about $5.5 billion in labor income and $9.1 billion in gross domestic product to Virginia’s economy annually, on top of the 74,000 jobs, mostly during the construction phase.

Jobs inside data centers include technicians, engineers, operations managers and security.

Technician and engineer positions are high-paid and don’t require a four-year degree, Bencks said. The highest-paying job currently listed with the Data Center Coalition is for an operations manager, which has a pay range of $125,000 to $150,000 annually, depending on the market and company, she said.

There are likely other positions that are higher-paid, she said, like “C-level employees working outside of the physical data center but still supporting operations.”

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics does not have a specific page for data center jobs, only broader fields like computer and information technology.

However, sites like Zip Recruiter that post open job listings can offer additional insight into data center pay.

According to that site, a data center operations technician could make between $18.85 and $20 per hour working in a Richmond data center. A cleaning technician could make $20 an hour at a Manassas facility. A data center in Sterling is offering between $65,000 and $85,000 yearly for a technician.

Creating these kinds of jobs in the Fredericksburg area would help mitigate out-commuting, Roberts said. Instead of driving to Northern Virginia to work at data centers, residents should have those opportunities more locally, he said.

“You’re creating a whole new pathway for jobs that have just not existed here in the past,” Roberts said. “Plus craftsmen, pipefitters, elevator installers, HVAC, electricians. That has a ripple effect.”

This indirect job creation is important, Bencks said.

“Focusing on direct jobs inside a data center understates the significant indirect impacts of the industry on employment,” Bencks said.

According to a 2023 report prepared for the Data Center Coalition by British consulting group PwC, every job in a data center supports six jobs elsewhere in the economy.

“This is what we often refer to as the data center ecosystem,” Bencks said. The jobs and economic development made possible by the industry include construction, HVAC manufacturers, restaurants, hotels and rental car companies, she said.

Schlossberg believes that auxiliary jobs should not be included in the job creation figure.

“Never ever before would you include the electrical jobs, the construction jobs, the plumbing jobs,” she said. “That’s not jobs creation. That’s ancillary, but as a local body, that’s not your long-term job development. … If there are so many jobs created, why are the parking lots so small?”

Bill Bennett, a Pittsylvania resident and former data center employee, is also skeptical of the high job promises from data center developers.

“These promises of high-tech, high-paid jobs are a myth,” he said. “It’s only for a handful of people, maybe a dozen. … All the technical work is farmed out somewhere else.”

Bennett was a field technician for data centers across Virginia from 2000 to 2024, and he worked in Wisconsin in the industry before that. He said that base pay for this role could be as low as $19 an hour, though he started at $24 an hour in the 1990s with a technical college degree.

He retired in April 2024, making $36 per hour.

“So in over 24 years, I’ve seen about a $12-an-hour raise,” Bennett said. “I don’t know any technicians in the industry who are making more than $40 an hour. With overtime, they may reach $100,000 a year occasionally, but that’s a rarity.”

Job and tax predictions in Pittsylvania

Anchorstone Advisors is behind Pittsylvania’s first-ever data center, which was approved in July and is located on a 950-acre parcel in the Ringgold part of the county. The development group told county officials that the project could create up to 500 jobs and contribute up to $120 million in tax revenue over a 10- to 15-year period.

Pittsylvania Economic Development Director Matt Rowe said these figures are not finalized, but Tom Gallagher with Anchorstone Advisors said they are all attainable.

Balico, the company behind the current proposal, promises even higher tax revenue and job creation.

The original 2,200-acre plan claimed it would create 700 jobs. These jobs would be “high-skill high-paying” roles earning between $150,000 and $200,000 yearly, according to Irfan Ali, founding member of Balico.

The scaled-back version of Balico’s proposal would need about 20 employees for each of the 12 396,000-square-foot data center buildings once buildout is complete, said Gould.

This would total about 240 jobs — many fewer than the 50 employees per 250,000 square feet estimated by JLARC, which add up to 950 jobs.

These permanent positions would pay about $105,000 yearly. Another 150 employees would work at the onsite power plant for an average salary of $90,000, Gould said.

The project would also need thousands of construction jobs at a variety of wages.

Some residents are critical of the job, salary and tax revenue figures. “I just don’t buy that,” said county resident Darrell Campbell in an interview.

When residents questioned Ali about these jobs and salary figures at a community outreach meeting in October, he doubled down, adding that most of the positions won’t require a four-year degree.

Bennett was unconvinced.

“It’s sad to me that people chase this stuff like squirrels chasing shiny objects, and [developers] make these promises of ‘up to’ however many high-paying jobs,” Bennett said. “Cities get suckered by the salesmen and this pie-in-the-sky kind of stuff.”

But according to Balico, the data center campus could be transformational for Pittsylvania County, according to a Nov. 14 statement from the company.

“[The project] will generate millions of dollars annually for education, public safety, and recreation throughout the county, all without relying on property owners to foot the bill.”