The year 2026 marks the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Cardinal News has embarked on a three-year project to tell the little-known stories of Virginia’s role in the march to independence. This project is supported, in part, by a grant from the Virginia American Revolution 250 Commission. Find all our stories from this project on the Cardinal 250 page. You can sign up for our monthly newsletter:

There are several reasons why the Patriots razed Virginia’s largest town in January 1776.

One was to keep the royal governor, Lord Dunmore, from using it as a supply base. Another was to punish the town’s many Loyalists.

The darkest reason is argued by Norfolk-born writer Andrew Lawler in a new book, “A Perfect Frenzy: A Royal Governor, His Black Allies, and the Crisis That Spurred the American Revolution.” Norfolk, with its narrow alleys, tall tenements, rum-soaked taverns, brothels, factories, capitalism, moneylenders, mixing of races, semi-free labor, restive Black population and wealthy Scottish industrialists, didn’t match the aristocrats’ plans for a rural slave society.

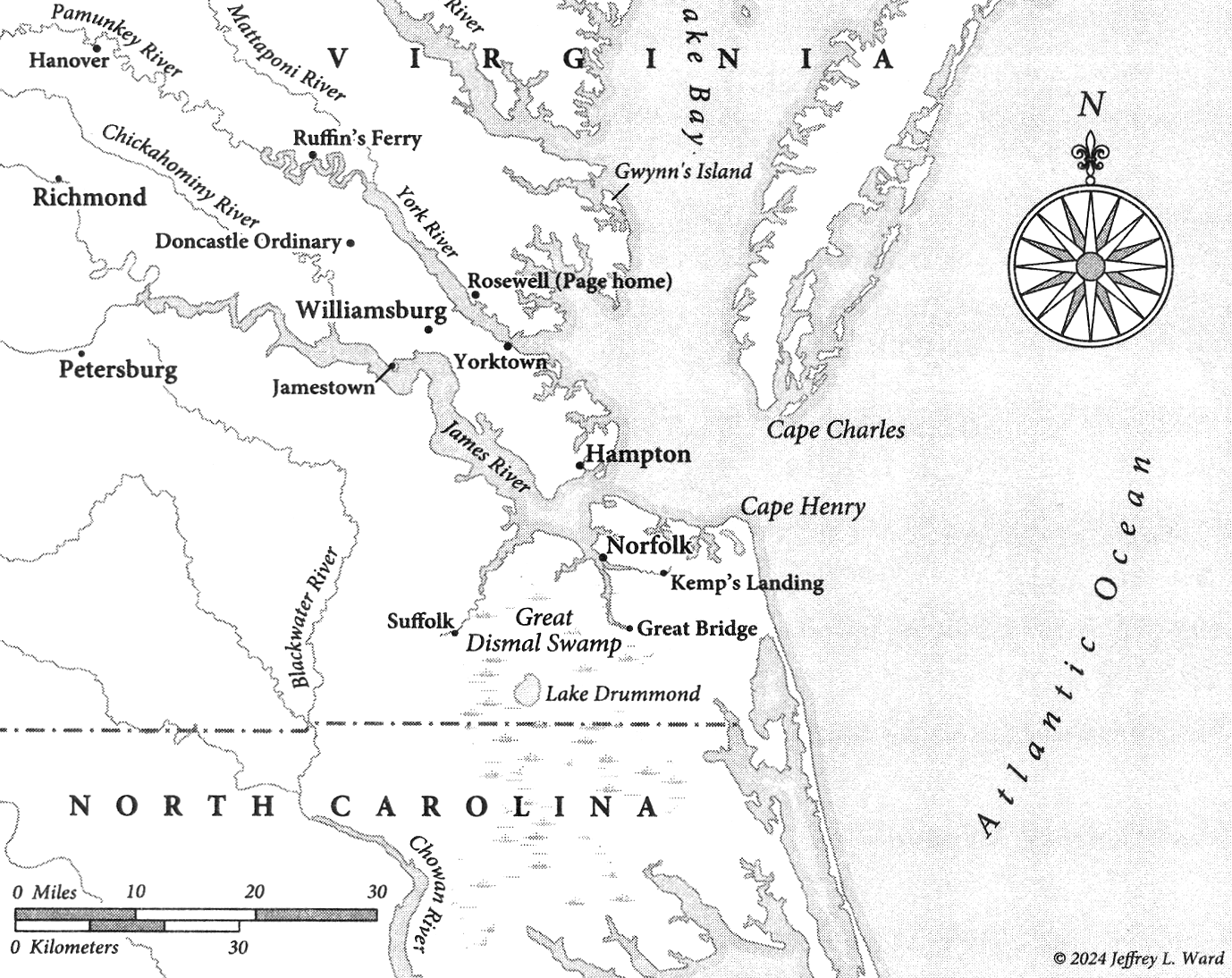

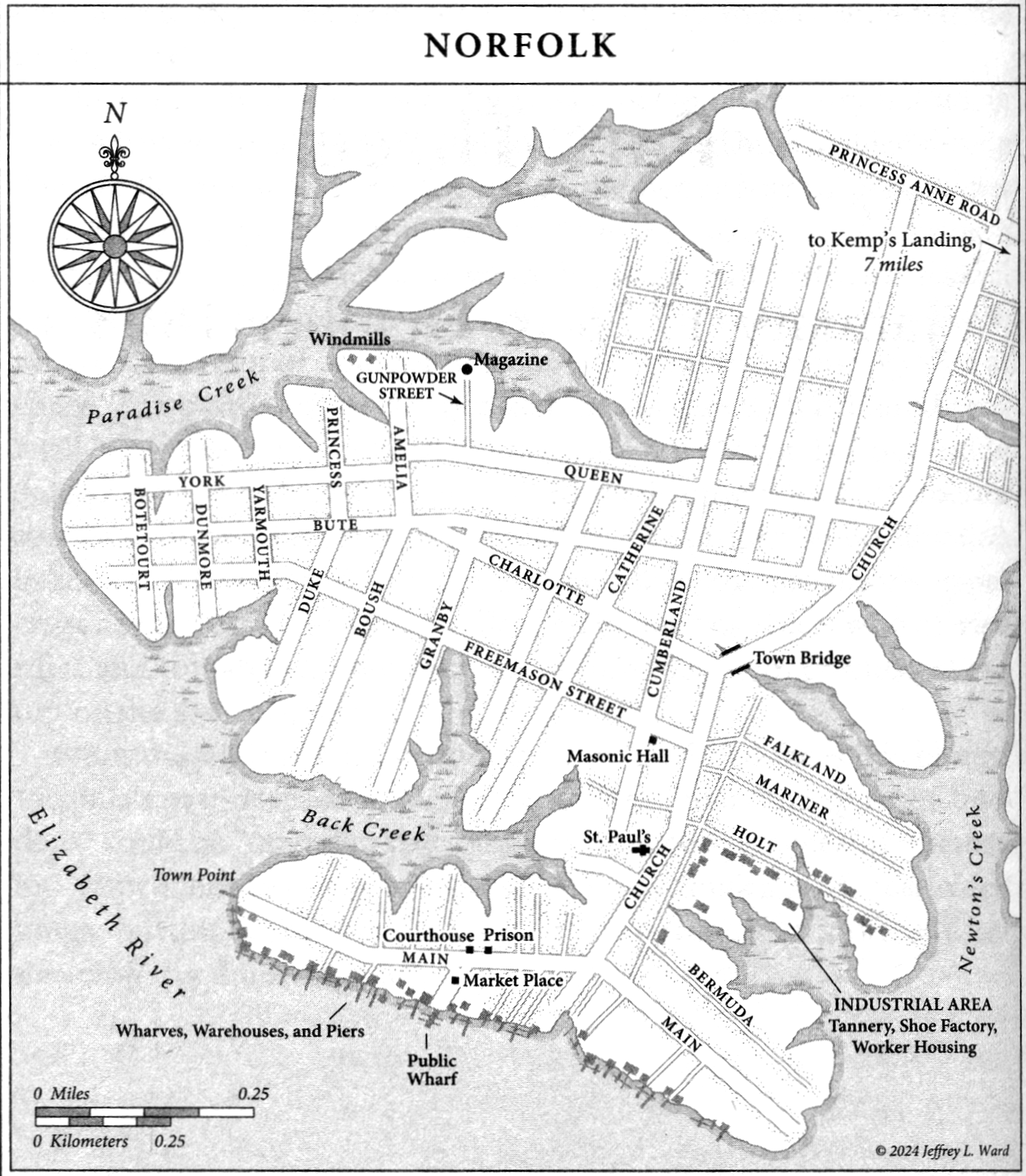

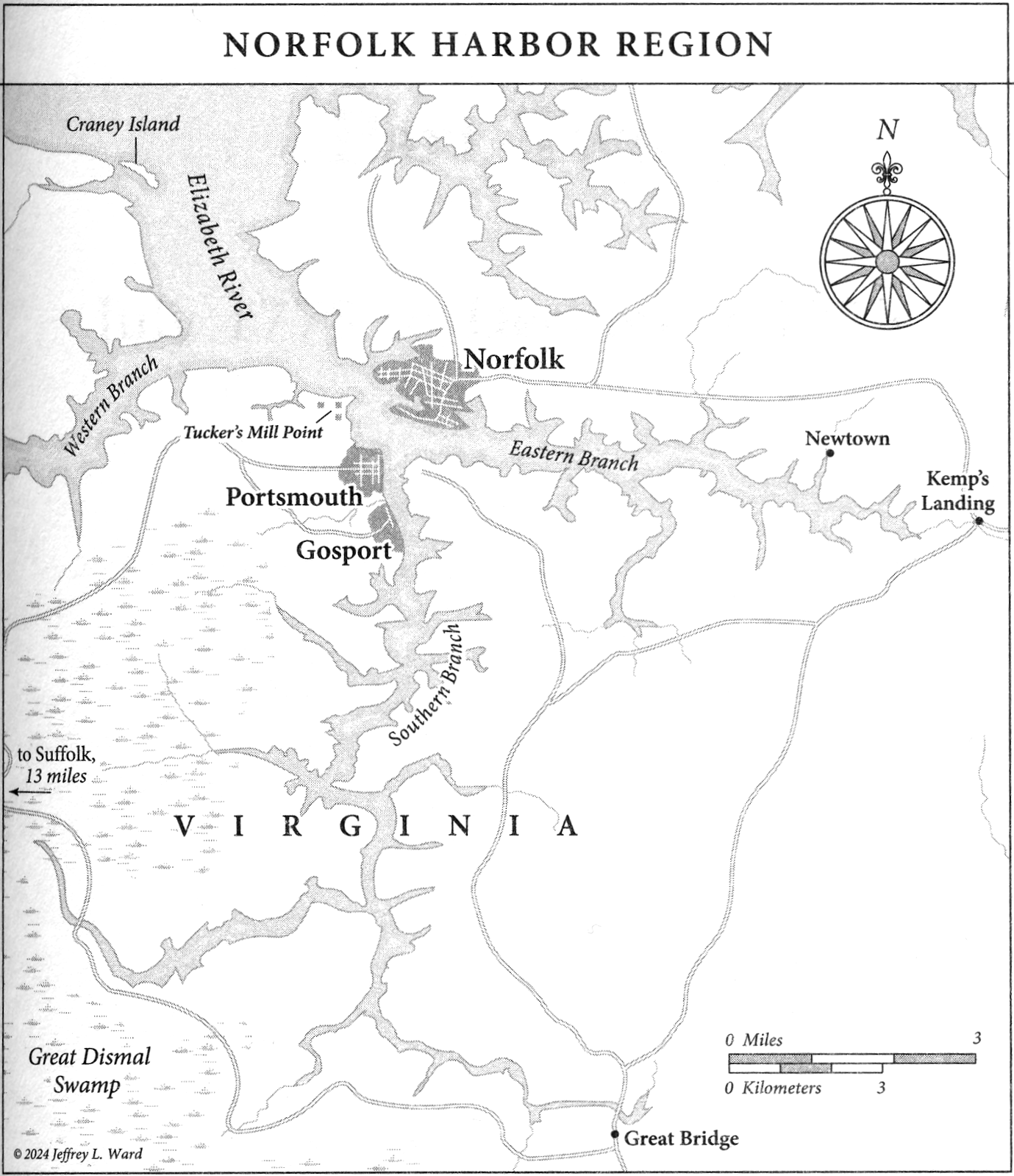

Norfolk was shaped by the water. The Elizabeth River offers a deep-water anchorage protected from Atlantic storms. On the river’s east bank, the town was founded in 1682. It became the headquarters of Scottish merchants who bought tobacco from the planters, sold them imported goods and enslaved persons, and loaned them money. By 1774, Norfolk had 1,300 buildings and 6,500 residents, three times as many as Williamsburg, Virginia’s capital.

Scottish profits from slave labor fueled an emergent capitalist/industrial society. Fifty enslaved people worked in a shoe factory. A tannery produced saddles, books, coach seats, and the whips used to compel obedience and punish wrong behavior in Virginia’s forced labor camps, also called plantations. Sailmakers supplied the Royal Navy. A distillery produced rum with molasses from the West Indies. Scotsman Andrew Sprowle ran a huge shipyard at nearby Gosport. The financial success of the Scottish businessmen created envy and resentment among the chronically cash-strapped planters.

The demand for labor gave enslaved people an opportunity to develop marketable skills, hire themselves out on their own time and bargain for a share of the profits. “Such arrangements were rare in the colony’s few other towns and unthinkable in the strictly policed tobacco fields, a reason the harbor became a magnet for unfree laborers,” Lawler wrote.

Tobacco planters considered Norfolk’s Blacks unruly and rebellious. “Women also thumbed their noses at white male authority … White females even competed in a footrace to win a fine piece of underclothing, a contest that would have scandalized Williamsburg’s far more staid society. Pirates, prostitutes, and prisoners on the lam haunted the dimly lit rum bars, and multiracial gangs bet, argued, and cheered together at bull-baiting contests.”

War came to this colorful urban mixing bowl in the pivotal year of 1775. On July 15, Lord Dunmore arrived on the naval sloop Otter, determined to make a stand against the Patriots. “He could count on the support of the area’s wealthy Scottish merchants, who were strongly attached to Great Britain,” Lawler wrote. “The enslaved Africans who labored in the warehouses, on the docks, and aboard ships as crew, pilots and watermen, also had ample reason to support the king’s cause. Many of the region’s white farmers, who mostly raised corn and hogs, also might prove sympathetic to his campaign against the tobacco gentry.”

In November 1775, more than 500 white men in Norfolk signed a pledge of loyalty to the king. Added to those in neighboring counties, the governor, on paper, had more than 3,000 Loyalists at his back.

But Dunmore needed more than paper support. With little help coming from the mother country, Dunmore offered freedom to people enslaved by Patriots — an existential threat to planters on edge against slave revolt and dependent on forced labor for their wealth and social position. The governor issued the proclamation on Nov. 15, 1775.

Meanwhile, Patriots debated Norfolk’s fate. The Virginia aristocrats looked to the classical world for models. For Thomas Jefferson, “the ancient fight between Rome and Carthage was a struggle pitting a republic led by noble and honest farmers against a gaudy and corrupt metropolis run by avaricious farmers,” Lawler wrote. “In 1775, Norfolk loomed in the planter’s mind as a colonial Carthage. Its dark and narrow alleys, squalid tenements, and grand mansions of wealthy merchants were at odds with his evolving vision of a republic of the soil … the very existence of fast-growing Norfolk, with its belching factories and crowded taverns where Blacks and whites mingled, might tug Virginia down the wrong path.”

On Oct. 31, 1775, Jefferson wrote to John Page, a member of Virginia’s Committee of Safety. A Latin phrase came to Jefferson’s mind: delenda est Carthago — Carthage must be destroyed. The ominous quote is attributed by historians to Roman hard-liner Cato the Elder. His words became reality in 146 B.C. when Roman general Scipio demolished the North African city, slaughtered most of the inhabitants, and sold the stunned survivors into slavery. The once-bustling site, mercantile center of the western Mediterranean lay in ruins for a hundred years.

At the bottom of his letter to Page, Jefferson wrote, in capital letters: “DELENDA EST NORFOLK.”

The sentence pronounced by Jefferson “alludes to Dunmore’s more or less effective use of the town and its vicinity as a base for his naval depredations,” in an annotation to the letter by Princeton University Press. Jefferson elsewhere made clear his contempt for urban agglomerations. “New York, for example, like London, seems to be a Cloacina of all the depravities of human nature,” he wrote in a 1823 letter. Again, he was alluding to Rome — Cloacina was the goddess of Rome’s great sewer, the Cloaca Maxima.

Page wrote to Jefferson on Nov. 11, “But at all Events rather than the Town should be garrisoned by our Enemies and a Trade opened for all the Scoundrels in the Country, we must be prepared to destroy it.”

As 1775 drew to a close, Patriot forces led by Cols. Robert Howe and William Woodford tightened the noose around Norfolk. On Dec. 14, they occupied the town. Dunmore’s sailors and marines took refuge aboard a floating city in the harbor along with Loyalist civilians and liberated Blacks. The Patriots ordered white men in Norfolk and Princess Anne counties to take a pledge of loyalty. Tensions rose as the Patriots blocked British attempts to gather food and fresh water. Howe and Woodford recommended to Edmund Pendleton, president of the Committee of Safety, that Norfolk be “totally destroyed” to deny its use to the British. It had little value to the Patriots, Howe said, and could not be held against a sea/land attack.

By Dec. 31, a thousand residents remained in the town. Dunmore warned them to flee, as he planned to destroy several waterfront warehouses used by Patriot snipers. On New Year’s Day, four warships with nearly 100 heavy guns opened up, filling the harbor with smoke. Dunmore also sent men in boats to ignite warehouses on the wharf. They also targeted a few buildings owned by known rebels. The solid, non-incendiary cannonballs did surprisingly little damage, although a ball lodged in the wall of St. Paul’s Church remains to impress visitors with Dunmore’s alleged barbarity.

As the sun set on New Year’s Day, observers in the harbor — many of whom had houses in town — noticed an ominous glow rising from neighborhoods away from the warehouses. It was the beginning of a rampage of arson and looting that lasted two full days and nights.

“‘The people in Norfolk were a foul nest of damned Tories,’ a resident heard a rebel soldier say, ‘and ought to have all their houses burnt and themselves burnt with them!’ … Not even privies were spared. Resident William Goodchild watched a shirtman [Patriot militiaman] set fire to his neighbor’s ‘necessary house.’ He encountered an officer who told him, ‘Yes, damn them, we will burn them all.'”

The Patriots did not spare the shipyard or the flour mills. When the orgy of destruction finally sputtered to a stop, Virginia’s commercial and industrial center was a smoking ruin.

Who was responsible for the annihilation of Norfolk? By the following year, tempers had cooled enough for the Patriots to assess the disaster. On Sept. 8, 1777, four committee members from the new General Assembly arrived to hear residents’ claims for damages.

Their devastating conclusion: “Very few of the houses were destroyed by the enemy, either from the cannonade or by the parties which landed on the wharves.” Troops from Virginia and North Carolina “most wantonly set fire to the greater part of the houses within the town … to burn all that came in their way.” In total, the Patriots destroyed 1,279 buildings, compared to Dunmore’s 54.

Patriot leaders, military and civilian, tried to distance themselves from the disaster. Commanders Howe and Woodford claimed the fire spread from the warehouses and that the Patriots had tried to douse them. Not a single eyewitness backed them up.

Pendleton, effective governor of revolutionary Virginia, claimed in a letter that he had initially opposed Norfolk’s burning. In fact, before hearing of the January 1 attack, he secretly ordered Howe to destroy Norfolk’s key industrial plants.

The report was hushed up, and in an era lacking investigative journalism, the Patriots succeeded in blaming the debacle on Dunmore. A perception of British barbarity nudged public opinion toward independence.

“Norfolk was destroyed not just because [its] people were thought to be insufficiently patriotic,” Lawler said in an interview from his home in Asheville. “It was destroyed really because it was an anomaly in Virginia, and people like Jefferson wanted to see a Virginia of small farms, and Norfolk didn’t fit into that … And the consequences in this case were dreadful, because Virginia became a backward place following the Revolution. People left, they went West, they went South, and the state never recovered from this kind of strange urbanicide, or kind of economic suicide, that was perpetrated by the tobacco elite. So it’s a great tragedy that even Thomas Jefferson later in his life regretted … all because they destroyed what could have been the economic engine for Virginia’s future.”

Free Black sailmaker Talbot Thompson bought the freedom of family members

Talbot Thompson was born in bondage. When his Scottish master, who owned the Raleigh Tavern in Williamsburg, went back to Scotland, “he was given the unique decision to decide which owner he wanted — and he chose himself,” Lawler said. “He was able to use his skills as a sailmaker, and at some point he moves to Norfolk where he began to make a good deal of money.

“Now, that was only the first step in colonial Virginia … in order to be officially free, to receive manumission documents, you had to get the full approval of the governor and his council. And as a result, very, very few people of African descent were able to go through these wickets. But Talbot Thompson did, partly because he was obviously a good diplomat, [and] he had some good contacts in the white community in Norfolk and Williamsburg.”

With profits from Royal Navy contracts, the sailmaker’s next goal was to purchase the freedom of his family. Jane, his wife, was enslaved by Robert Tucker, a former mayor of Norfolk.

On Sept. 16, 1768, Thompson attended the auction of his wife and children. He bid five pounds for Jane, and no one challenged him. But two sons, ship pilots with valuable skills, were sold to white owners.

Jane succeeded in winning freedom from the governor, and the Thompsons became the only officially free Black couple in Colonial Virginia. While free, they were not equal — Talbot could not vote, serve on juries or join the militia. Still, the Thompsons built a prosperous middle-class life. Their house on Cumberland Street had a dairy and an orchard. They even became investors, owning other homes — and at least one enslaved person.

“Very often apologists for slavery will say, ‘Well, Black people had slaves,'” Lawler said. “But in this case there’s really good circumstantial evidence that Talbot and Jane Thompson were purchasing their relatives, so that their father, their mothers, their brothers, their sister … were no longer being enslaved by white people. To own slaves as a Black person in colonial Virginia, almost invariably you were trying to protect your relatives. You were trying to bring them within your community.”

Talbot and Jane Thompson lost almost everything they had in the Revolution. By the start of 1776, Jane fled Virginia. She and Talbot made their home in New York, where he died in 1782. In 1783, Jane boarded a ship to Canada, where she joined a fledgling Black colony, fighting hunger, harsh weather and white hostility. Many family members gave up on Canada and sailed for a new colony in West Africa. The aging Jane stayed behind. At some unrecorded date, she died in poverty on the frigid coast of Nova Scotia.

Patrick Henry manipulated white farmers into allying with the tobacco elite

Early on the morning of April 21, 1775, under cover of darkness, Lord Dunmore had the gunpowder stores in Williamsburg’s magazine transferred to a navy ship, infuriating the Patriots.

Unlike his tobacco-planter friends, Patrick Henry was a trial lawyer who rode the circuit and interacted with small farmers who cared little about tea, taxes, tariffs and Intolerable Acts. “These things will not affect them,” Henry wrote. “But tell them of the robbery of the Magazine, and that the next step will be to disarm them.”

Why was this alarming? Many small farmers owned a few enslaved people, and “the only thing that kept them safe, in their minds, was owning a gun,” Lawler said. “At any moment, that field hand might slit your throat, you might be poisoned by the cook, you lived in constant fear of revenge. So Patrick Henry, very, very cleverly, was able to put out this idea that the British were going to disarm white Virginians, which has no basis in fact, and really inspire people to join up with Patriot militia, which until then was made up primarily of well-to-do people.”

Andrew Lawler’s “A Perfect Frenzy” ($30) can be purchased through independent booksellers and can also be ordered online: https://groveatlantic.com/book/a-perfect-frenzy/.