To create narratives from historical sources isn’t an exact science, but there are certain rules of thumb. You must always be on the lookout for personal biases and other factors that can obscure the past. Few sources can provide more insight than testimony from an individual who lived through an historical event. Comparing multiple sources is an adequate substitute for living memory.

For local historian Holly Kozelsky, multiple sources helped her rediscover a time when the Ku Klux Klan established a presence in Martinsville via the local churches.

“I use various sources, pull them together and write it,” Kozelsky said about the method behind her work. “When I come across matters that have a theme to them…I pull it out and I research it more.”

Kozelsky is the director of the Martinsville-Henry County Historical Society where, among other tasks, she is responsible for a daily historical column. For the past five years, Kozelsky has made a name for herself writing about interesting historical tidbits about Martinsville’s past.

“Presently, this column is on the Historical Society’s website,” Kozelsky said. “It’s a long term project. It’s entertaining for people to read it. People like reading about history, and it’s an extremely valuable source for me to understand local history.”

Clippings shed light on a different time

The columns are based on information taken from documents, like newspaper clippings. She said that while each document is an important source of information, occasionally multiple documents can come together and tell a broader story.

She explained that for her column titled “KKK got its foothold here through churches,” a series of disparate newspaper clippings shed light on an interesting, and largely forgotten, time in Martinsville’s past. Linking these clippings was a simple keyword search item, “KKK.”

“The KKK was one of the themes that I noticed pop up,” Kozelsky said, later adding, “I came across a few entries of the Klan that I had not come across before, in our area.”

Kozelsky wasn’t cherry picking random stories about the Klan throughout Martinsville’s history. The proximity of the dates was what caught Kozelsky’s attention.

“When I was reading the November papers, I just kept on seeing Klan here, Klan there, everywhere you turn around they are making appearances,” Kozelsky said. This led her to believe this period of a few years was significant.

“It was exactly 100 years ago that the Ku Klux Klan entrenched itself into the fabric of Martinsville life,” Kozelsky wrote. KKK brass were allowed to proselytize their own version of the gospel, and they didn’t come empty-handed.

“Showy donations of money and flags to churches, civic organizations, school libraries and even the mayor in front of the courthouse paved the way for the Jim Bob Bondurant Ku Klux Klan No. 29, starting in the fall of 1924.”

The KKK No. 29 was one of several regional KKK chapters, alongside chapters in Danville and other places throughout the region. According to the Encyclopedia Virginia, the Klan was at its height around the 1870s when statewide membership numbered in the thousands. In the ensuing decades, their numbers dwindled, but they didn’t disappear entirely.

According to the Bill of Rights Institute, the 1920s was a decade of resurgence for the Klan. Writings from the likes of Marcus Garvey’s Declaration of the Rights of the Negro People of the World, published in 1920, contributed to a growing national sentiment at odds with what the Klan preached.

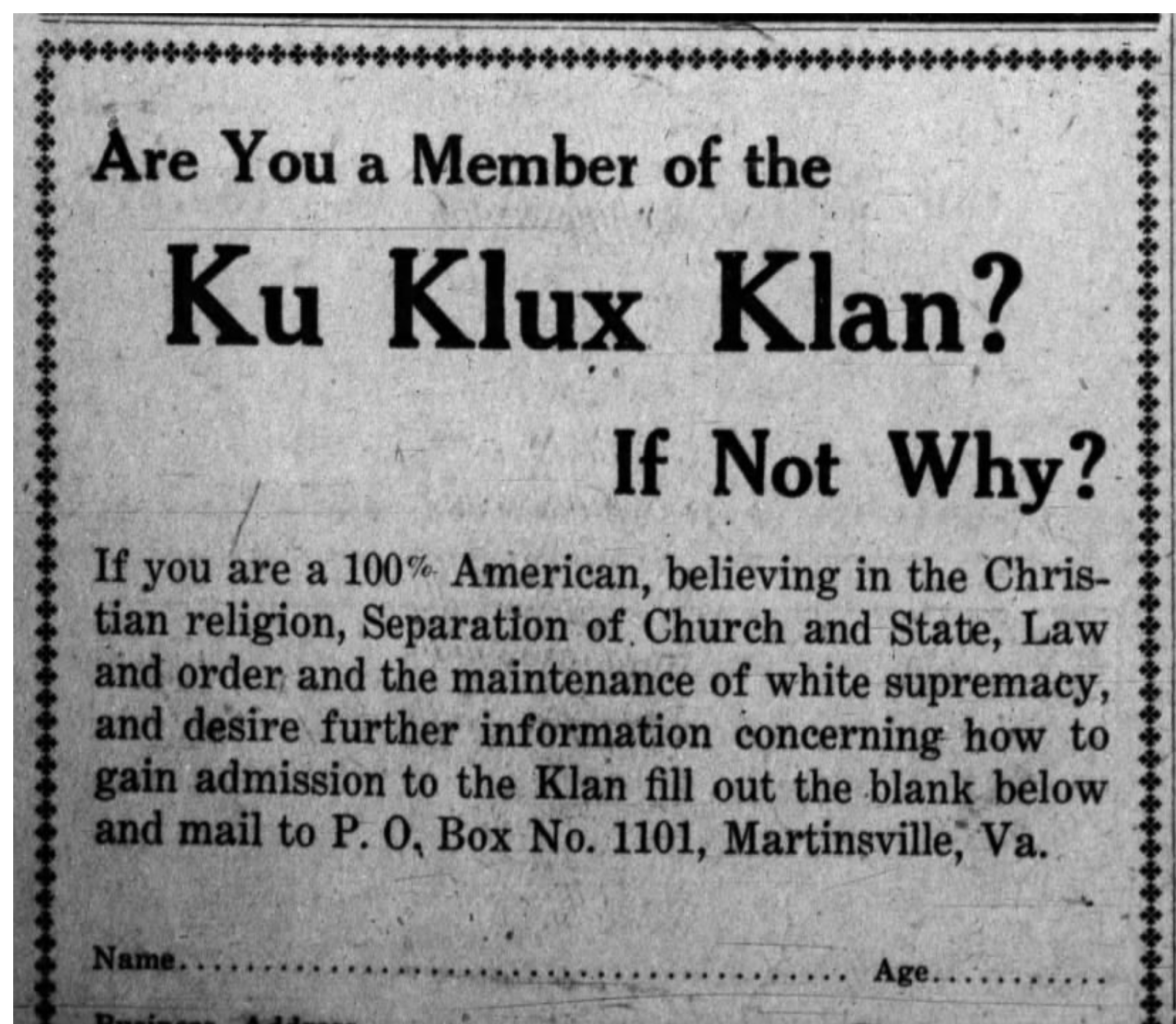

Some groups within the Klan sought to capitalize, according to the institute. Ads like the ones published in the Henry Bulletin on Nov. 7, 1924, spoke to the growing sentiment at the time.

“Are You a Member of the Ku Klux Klan?” asked the ad the Klan took out in the Bulletin. “If Not Why? If you are a 100% American, believing in the Christian religion, Separation of Church and State, Law and order and the maintenance of white supremacy, and desire further information concerning how to gain admission to the Klan, fill out the blank below and mail to…”

It wasn’t out of the ordinary for the chapters to send out emissaries to gathering places in the hopes of further bolstering their numbers.

“The Klan was in every Southern state, about every city in the South,” said Charisse Hairston, director of the FAHI African American Museum. “I wasn’t surprised that it was in Martinsville because we’re a rural community.”

Kozelsky notes that the Klan’s message almost reached complete saturation, as they ventured beyond Sunday pews and onto community soapboxes.

“A group of seven Klansmen presented a short ceremony while giving the gift of a silk American flag,” Kozelsky wrote. “The Henry Bulletin reported that all of the churches were full, some to the point that latecomers had to be denied entry.”

Kozelsky said descriptions like this are important to historians because they add important detail and color to historic events. Several things can be gleaned from the statement “latecomers had to be denied entry.”

“This says a couple of things,” Kozelsky said. “It says that a lot of people went to it. It immediately brings to mind that these days churches are largely…half-full. For a person who goes to church today, they can see that churches were so full back then, people couldn’t get in.”

“This is vitally important,” Kozelsky said, adding that finding these kinds of colorful quotes demands time and resources. “If this was your only project, a person might be able to dig up more resources.”

Kozelsky added that there can be such a thing as too much color.

“Sometimes you have to get straight to the point,” Kozelsky said. “Too much color that is extraneous, unnecessary, doesn’t fit, or is boring can be distracting.”

Tone is another important aspect, with Kozelsky emphasizing the importance of not matching a document’s tone, particularly on sensitive topics.

“Oh, they were joyful,” Kozelsky said about some of the newspaper clippings and offered an explanation. “We’re looking at it with the benefit of time. Our generation looks at a burning cross and it scares us. The KKK didn’t have the legacy behind it that it does now.”

Kozelsky and others speculated that this didn’t reflect the sentiment throughout the Martinsville community.

“Obviously these clips were written by white people who, in my opinion, had little to no thoughts on what Black people would feel like seeing the Klan,” Kozelsky said.

‘From robes to suits’

The omission of Black churches in the coverage at the time was little surprise to Tyler Millner and John Adams, pastors of the Morning Star Holy Church and First Galilee Missionary Baptist Church, respectively.

Millner and Adams said the Klan exploited an ideological rift with a throughline connecting past and present.

Adams said the sentiment that warmly invited the Klan into Martinsville, in some measure still exists, while the wardrobe has changed from robes to suits. The iconography, more than the ideology, contributes to the Klan’s downfall.

Still, Adams and Millner said the Klan’s reputation makes it difficult for them to cozy up to a community like they were once able to.

“Whenever I hear [KKK] I go into a defensive mode,” Adams said. “That is because I am a preacher of the gospel. My sole concern is promoting love, unity and fellowship. My impression of the Klan is they promoted the opposite…so right off the bat, when I hear the term my defense mechanism comes up.”

Adams, though hesitant to delve into the motivations of a klansman, said the church’ s general popularity at the time could have played a role in the strategy to introduce themselves to Martinsville.

“They understood that it was the church. Especially in the South, they understood that it was the church that they could have the biggest influence,” Adams said. “The church in the South was part of the culture; it still is in many ways. They chose the church because it was the easiest way to interject their beliefs.”

Even then, Kozelsky said there was at least some mention of pushback with some clips mentioning that some churches didn’t fall for the Klan’s overtures.

Adams said if Martinsville is a far cry from the city it once was, it is a transformation that took generations, with more work needed.

“Freedom is never won but every generation has an obstacle to win,” Adams said, quoting Martin Luther King. “It’s our job to win this generation.”