Emporia took a hard blow last week when the Georgia-Pacific plywood mill announced it’s closing, leaving 550 people out of work.

That follows another hard blow last year, when the Boar’s Head Provision Co. meat plant in nearby Jarratt in Greensville County closed.

No community wants to lose a major employer; between them, Emporia and Greensville County have now lost two in less than a year’s time.

These two plant closings are unrelated — Boar’s Head was linked to a listeria outbreak that led to 10 deaths across the country. That’s a tragedy, but it may not directly stem from a public policy choice. However, Georgia-Pacific cited national declines in homebuilding and homebuying, and those are very much connected to public policy.

That leads to this conclusion: Neither political party has a good solution yet to high housing prices — and workers in Emporia are now paying the price for that.

In its statement about the Emporia plant, Georgia-Pacific cited two trends: “Housing affordability challenges and a 30-year low in existing home sales are impacting our plywood business, as many of our plywood products are used in repair and remodel projects, which often occur when homes change ownership.”

Georgia-Pacific is right: Houses are becoming more unaffordable and home sales are dropping.

This is not a situation that has developed suddenly. It’s been developing for a long time, which means we can’t blame the problem on any one politician or party. Both parties, though, have been unable to devise a solution.

Let’s review the basic facts.

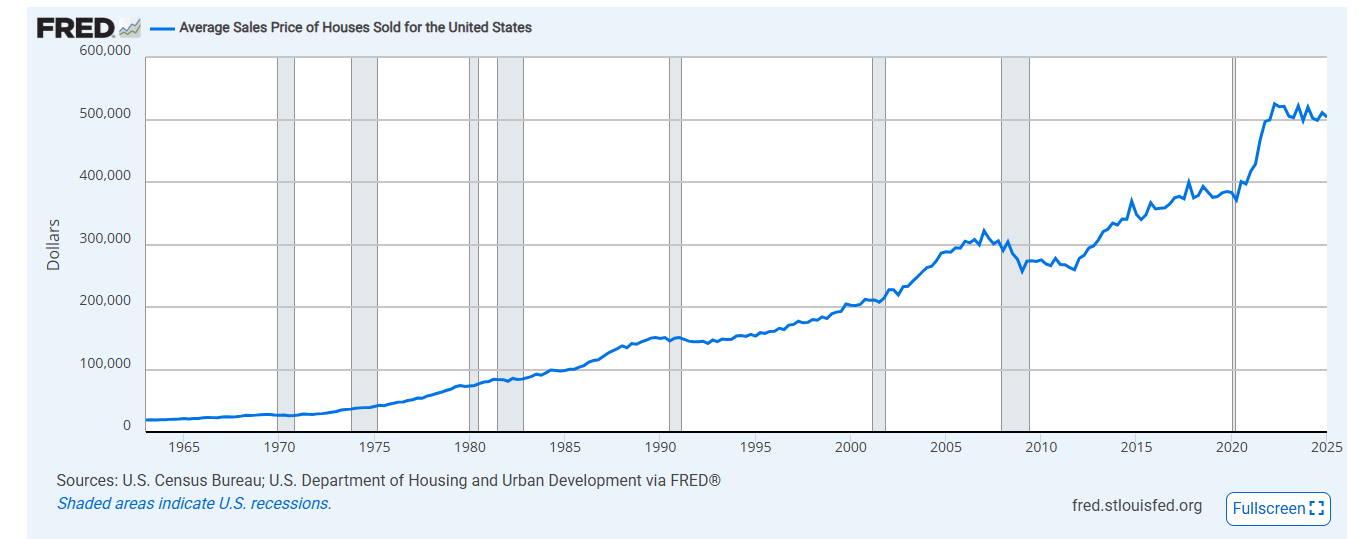

1. Housing prices are rising faster than income

From 2000 to 2023, home values increased by 162% while incomes increased by 78%, according to federal data compiled by the LBM Journal, a trade publication for lumberyards. Furthermore, that gap is increasing. “The divide between home prices and income has caused the house-price-to-income ratio to greatly exceed what many financial experts consider healthy,” LBM reports. “In other words, buying a home should cost about 2.6x what the average American makes in a year. In reality, it costs 5.8x the median household income — making homeownership an increasingly elusive dream for today’s home buyers.”

In March, the median price of a home in the United States rose above $400,000 for the first time, according to the National Association of Realtors. That’s good news for sellers, but not for buyers — and not for companies such as Georgia-Pacific that sell supplies that new homebuyers might need.

Why have housing prices gone up so much? There are lots of reasons, but ultimately it comes down to supply and demand. The demand has been higher than the supply. Low interest rates (which politicians often like because that means people can borrow money more easily) have made it easier to buy houses — which has then driven up the cost. Of course, we could also flip the question around and ask why incomes haven’t risen faster. For our purposes today, we’ll just stick to the basic problem: Housing prices are making it hard for many people to buy houses, be those new houses or older fixer-uppers, and the implications of that have now filtered down to Emporia.

2. Home sales are at their lowest point since 1995

Let’s deal with the sales of existing homes first, since they constitute 90% of the home sales market.

They’re declining. In 2024, home sales hit their lowest point since 1995. There are multiple reasons for this: The rising price of buying a house is certainly one of them. So are higher mortgage rates and the “lock-in” effect that happens when people who bought houses when mortgage rates were lower feel “locked in” and are reluctant to sell and buy another house because they know they’ll face higher rates. Broader uncertainty about the economy also depresses home buying. The National Association of Realtors reports that home sales in March fell 5.9% from February (even though March had three more days) and are now 2.4% below what they were a year ago.

The last time home sales were this low, Bill Clinton was president, “Gangsta’s Paradise” by Coolio was the top song of the year and nobody had a Facebook account because social media hadn’t been invented yet.

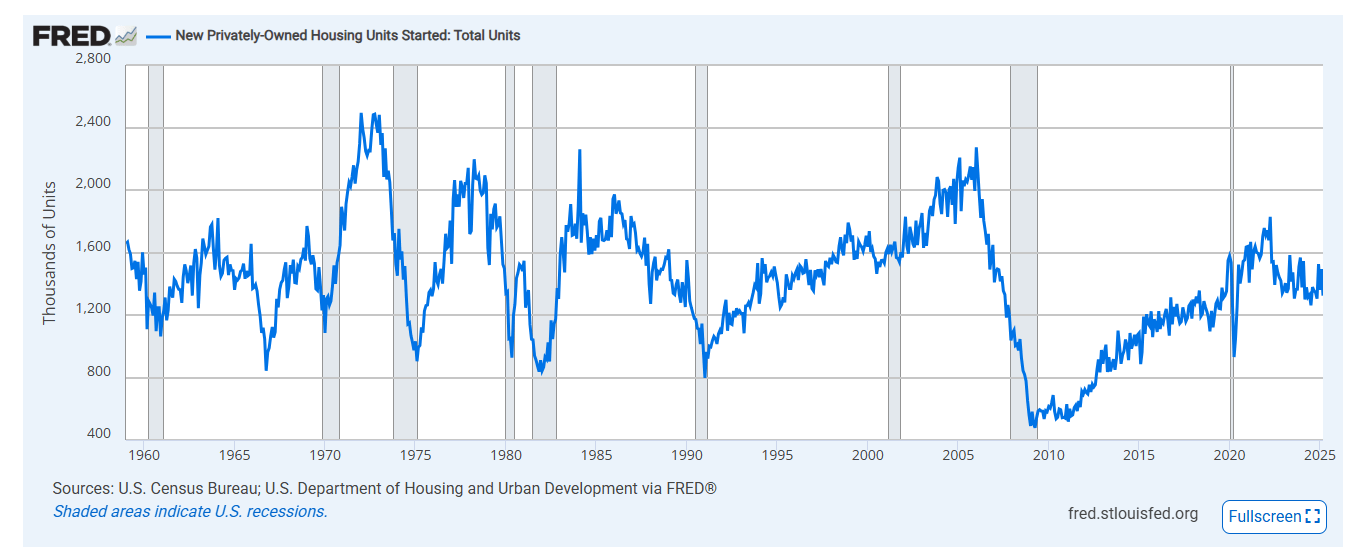

3. Housing starts are back to the same level as 1995

While the solution to the imbalance between the supply of housing and the demand for housing is to increase supply, that’s not really happening either. Housing starts are now back to the same level they were in 1995, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. They crashed during the Great Recession and have recovered some since then, but remain lower than they were in much of the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s. It may not seem that way in some places — I’ve seen lots of construction along Peppers Ferry Road in Montgomery County, for instance — but those are national aberrations.

Home sales and home starts typically go up and down, much like the stock market. However, it’s important to note here that these aren’t simply temporary layoffs in Emporia based on transitory economic ups and downs; this is a permanent plant closure, which suggests that Georgia-Pacific sees no end in sight to some of these trends.

4. Multiple trends are making it harder to build more housing

We’re now seeing both political parties start to grapple with housing prices, but solutions have been elusive. Gov. Glenn Youngkin, a Republican, says the solution is that we need to build more houses — on the theory that a greater supply will bring down prices. He’s not wrong. However, we often see localities immersed in controversy whenever a large housing project is proposed; we’ve seen this happen recently in both Democratic localities (Roanoke, with Evans Spring) and Republican ones (Pittsylvania County, with Axton Properties). In many cases, such as Salem with the HopeTree project and Lynchburg with the Wigginton Road development, the main objection has been over location. Still, the bottom line is the same: While there may be broad agreement that more housing is needed, the specifics of actual developments are often controversial.

To that extent, housing is much like energy: We all want the lights to come on, but few people want a power plant next door. Likewise, a president or a governor can declare that we need more housing, but that policy ultimately depends on local governments to approve rezoning requests, which they’re often not keen on doing because of neighborhood objections. In the most recent General Assembly session, state Sen. Schuyler VanValkenburg, D-Henrico County, introduced a bill to call on localities to meet certain housing targets, but it failed out of concerns that these would constitute state mandates.

A shortage of skilled trades workers also limits housing. This is part of the economy that could benefit from more immigration, yet President Donald Trump’s immigration policies discourage that. (One study found that 31% of the “undocumented” population works in construction.) Trump’s tariffs may drive up some construction costs, as well. Nearly one-third of construction supplies are imported. The biggest source of nails used in American construction? China. The price of those nails just went up. Even if the nail industry decided to build American plants, it might take years for that to happen, while the prices have gone up now. I discussed these and other political obstacles to creating more housing in a column last year. The reality is that neither party has a good solution yet to high housing prices. Democratic initiatives may run counter to no-growth or slow-growth policies in many Democratic-controlled suburbs; Republican initiatives run afoul of immigration and tariffs. In the meantime, 550 people in Emporia are out of work.

5. Emporia and Greensville County face bigger challenges than just these plant closings

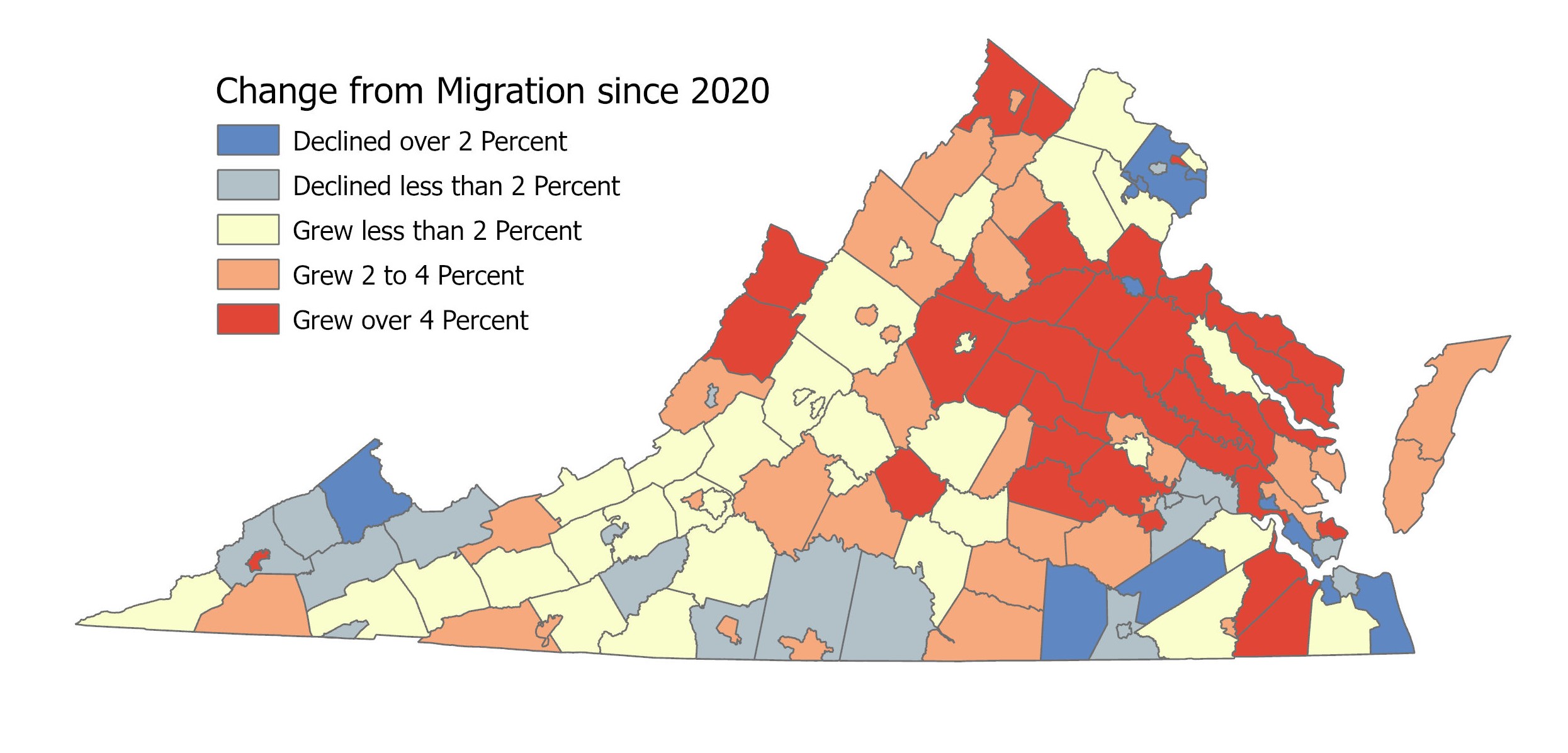

The big demographic story since the pandemic has been the large migration of people out of America’s urban areas and into rural areas — well, some rural areas. The portion of eastern Southside around Emporia is one of the few places that hasn’t seen that migration. On the contrary, Emporia and Greensville County, plus neighboring Brunswick and Sussex counties, continue to see more people moving out than moving in. Many rural counties continue to see their populations decline, but only because deaths outnumber both births and that net in-migration. In eastern Southside, though, we see localities that are losing population both ways, through the hearse and the moving van.

With that double whammy, eastern Southside has now surpassed the coal counties of Southwest Virginia as the most hard-luck part of the state. Three of the four localities with the biggest population declines are in eastern Southside. Since 2020, Sussex County has lost a bigger share of its population than any other place in Virginia — it’s down 8.6%. Buchanan County in Southwest Virginia is second at -6.4%, Brunswick County third at -6.2%, Greensville County fourth at -4.7%.

At a time when the workplace prizes education, Emporia ranks as the least-educated locality in Virginia — 24.3% of its adult population 25 and over doesn’t have a high school diploma, according to the National Institutes of Health. In Greensville County, the figure is 20.9%; in Brunswick, 20.6%, ranking them fifth and sixth lowest in the state. The statewide average is 8.7%.

Whatever the short-term fix for Emporia and Greensville County might be, the long-term solution seems to be to upgrade the educational level of its workforce, especially since the number of available workers has now been suddenly expanded. However, if Emporia wants a plywood mill, it needs the entire country to figure out a way to create more housing.

Early voting is now underway in June 17 primaries

Democrats are holding statewide primaries for lieutenant governor and attorney general. Both parties are also holding scattered primaries for House of Delegates and local offices. We have a list of who’s running for what on our Voter Guide. I’ll look at the early voting trends in Friday’s edition of West of the Capital, our weekly political newsletter. You can sign up for that or any of our other free newsletters here: