Want more on Virginia’s population trends? We’ve collected all our demographic coverage in one place.

We also have a March 26 podcast about migration trends in Virginia. Find it on our podcast page.

Virginia lies over top of an earthquake zone, something we’re occasionally reminded of.

Some of us felt the 2011 earthquake near Mineral in Louisa County that shook even the Washington Monument and damaged two schools in Louisa so severely they were closed for the rest of the school year. Others felt the much smaller earthquake that originated near Dillwyn in Buckingham County.

The strongest Virginia quake in recorded times was in 1897 near Narrows in Giles County; that tremor brought down chimneys as far away as Bedford County and damaged others from Lexington down into North Carolina.

We are now living through another seismic event, except this one doesn’t involve geology; it involves demography.

The latest Census Bureau estimates confirm some previously reported trends — and provide some surprising new insights into them. Among the highlights:

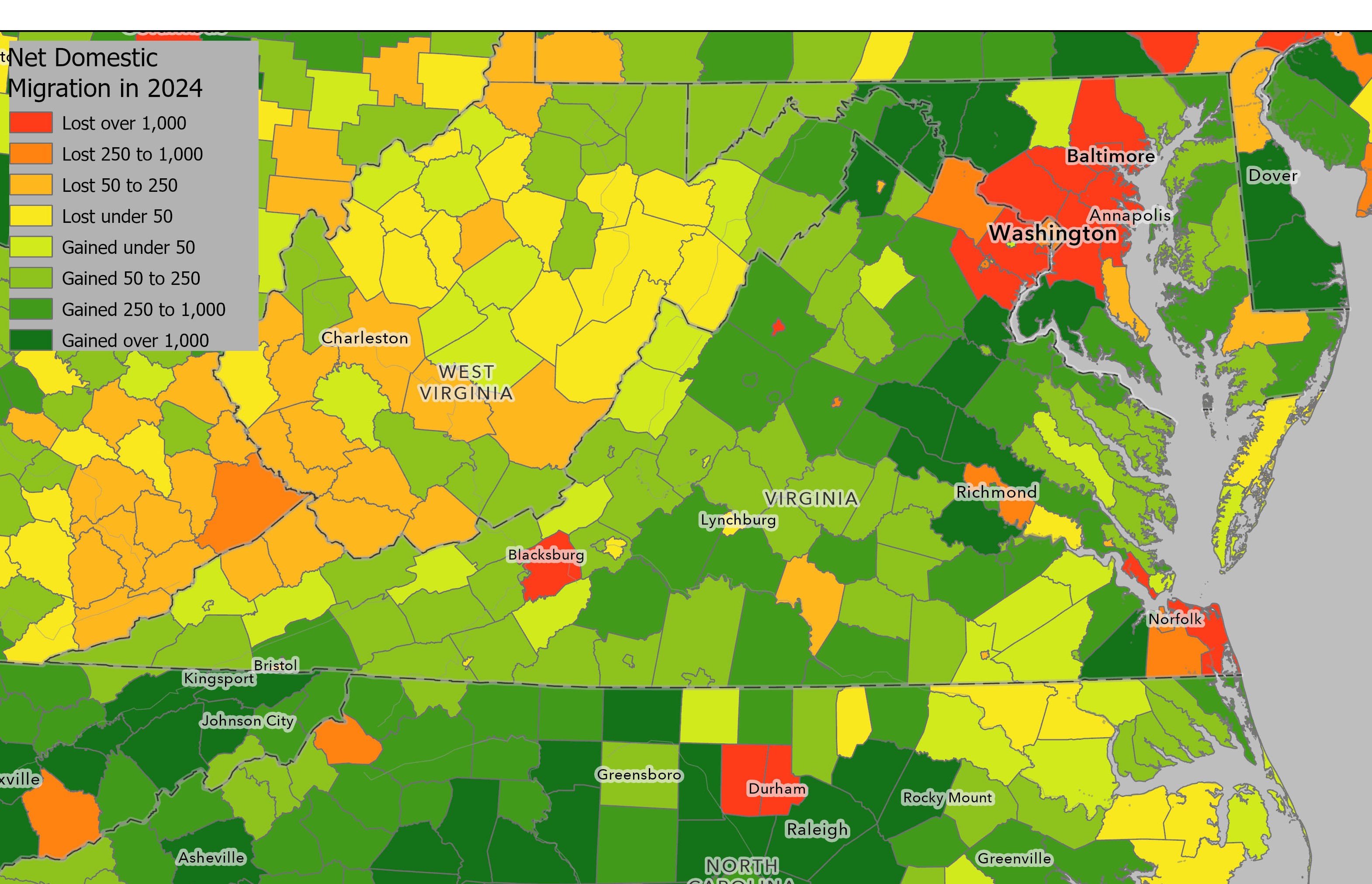

- It’s rural areas, not the state’s metro areas, that are responsible for Virginia becoming a net in-migration state for the first time in more than a decade.

- Almost every rural county in Virginia is now seeing more people move in than move out.

- This includes the coal-producing counties of Southwest Virginia, which are collectively now gaining people rather than losing them.

- In Roanoke, the exodus of residents has nearly ground to a halt.

- Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads continue to hemorrhage people, although the outflows are slowing.

Before we get into examining these trends, a few words (or maybe more than a few) about where they come from. Both the Census Bureau and the Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service at the University of Virginia produce annual population estimates for each county and city in the state (and, in the case of the Census Bureau, for every locality nationwide). Here’s the key thing: They use different methods to arrive at these numbers.

Broadly speaking, both entities arrive at the same general picture, although the precise numbers differ. The value for us is that one helps provide validation of the other, so if some of these trends sound familiar to you, that’s because Weldon Cooper has already highlighted them in its numbers, which came out in January. However, the Census Bureau also offers more detailed figures in some categories, which is what we’re going to mine today.

Rural Virginia is saving Virginia, demographically speaking

Population only changes four ways, and they are grouped into two categories: births vs. deaths and people moving in vs. people moving out. Both are important, but the latter is more so because it involves more choice. If more people are choosing to move away than to move here, they’re essentially “voting with their feet,” as Ronald Reagan used to say. Starting in 2014, Virginia saw net out-migration every year until this one. Glenn Youngkin made that part of his campaign for governor and has tracked these figures more closely than any governor I’m aware of. He attributed the state’s net out-migration to high taxes; Democrats blamed high housing costs and lack of transportation, especially in Northern Virginia, which has been the main source of that net out-migration. Feel free to debate all that. Today we’ll stick to the numbers.

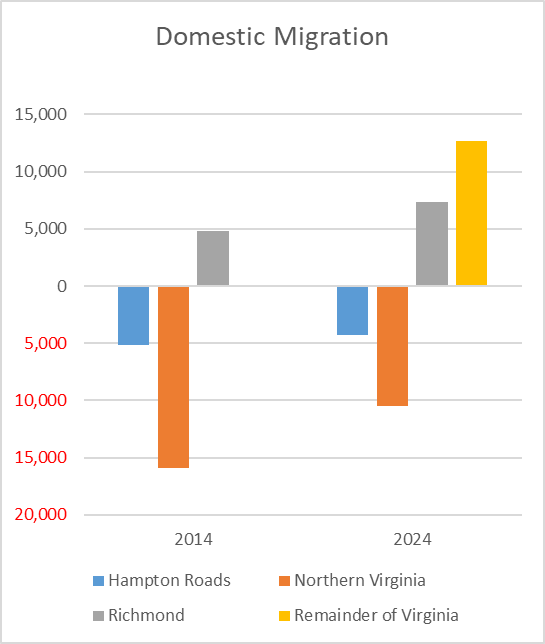

What these census estimates show is how, if you just look at the state’s metro areas, Virginia would still be seeing net out-migration. It’s a dramatic uptick in net in-migration in rural areas that is keeping Virginia in the black, population-wise. The state’s two biggest metros — Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads — are losing people through net out-migration. It’s rural Virginia and the Richmond area that are seeing net in-migration, and, of the two, rural Virginia is seeing more.

The specific numbers: The Census Bureau says that overall, Virginia saw net out-migration of -9,646 in the year ending July 1, 2023, but net in-migration of 5,284 for the year ending July 1, 2024. That’s the equivalent of losing Bath and Craig counties one year and gaining the city of Covington the next. Note that these figures are only for domestic migration — people moving from one place in the United States to another. If we count international migration — immigration — things get more complicated. The Census Bureau last year changed its methodology for estimating immigration, producing higher estimates than before, and there’s some dispute as to whether those estimates are correct. I’ll deal with that in more detail in a future column because that dispute makes a difference as to whether Fairfax County is gaining population slightly (the Census Bureau estimate) or losing slightly (the Weldon Cooper estimate). For our purposes today, that doesn’t matter because even with the higher Census Bureau estimates on immigration, the bureau shows immigration estimates in many rural areas to be in single digits and, in some places, at zero. Immigration is mostly still an urban phenomenon.

Almost every county is now seeing a ‘rural renaissance‘

This is the biggest demographic shift we’ve seen since the pandemic. Rural counties that once saw more people move out than move in are now seeing exactly the opposite. This has been going on for several years now; some counties saw this trend start before the pandemic, but the COVID shutdown accelerated these moves. However, we’re now seeing enough data to conclude that this is a real trend and not a one- or two-year aberration.

Hamilton Lombard, a demographer at the Weldon Cooper Center, provides this analysis of how broad-based this trend now is: “In 2014, only 48 of Virginia’s 95 counties were attracting more new residents than they were losing to other parts of the country, last year that number was 84. Outside the Urban Crescent only five counties had negative domestic migration in 2024, the lowest number in decades. Relative to their population size, the Coalfield counties have seen the biggest shift from losing over 2,300 residents in 2014 to attracting 377 last year. On the opposite side of Virginia, the Northern Neck shifted from attracting 131 new residents from other parts of the country to attracting 1,194 last year.”

Note: Montgomery County is one of the counties that shows up on the losing side, which sure doesn’t seem right given all the construction along Peppers Ferry Road. However, estimates in places with colleges are often skewed by the large number of college graduates who move out every year, so treat the numbers in any college community with caution.

Also, keep in mind that a locality that has net in-migration can still lose population — if deaths outnumber both births and net in-migration — and in most rural localities, deaths are the main population driver. That means, yes, most of rural Virginia is still losing population; it’s just not losing as much as it was.

Overall, the coal counties are now seeing net in-migration

The keyword here is “overall.” Two counties in the state’s westernmost corner — Buchanan and Dickenson — are still seeing net out-migration, but those numbers are topped by their neighbors. More importantly, Buchanan and Dickenson are seeing their out-migration slow. In 2022, Buchanan County saw net out-migration of -292 people; last year it was -117. Dickenson’s was -100 in 2021, but that fell to -4 in 2022 and -2 in 2023 before ticking back up to -61 last year. On the other hand, Wise County saw out-migration from 2000 to 2022 and has been on the plus side the past two years. Tazewell County’s net migration in 2022 was zero, but last year it saw 91 more people move in than move out. Russell County’s migration was also zero in 2022, but now is on the plus side by 203 in 2023 and 36 in 2024.

Roanoke’s out-migration has dropped to almost nothing

Roanoke was proud to see its population climb back above 100,000 in 2022, the first time since 1980 it had been in the six-digit range. Since then, though, population estimates have consistently shown the city losing population again.

The Census Bureau estimates have shown large population outflows every year since the last headcount — a net out-migration of -1,127 in 2021, -1,093 in 2022 and -586 in 2023. Now the Census Bureau shows that slowing to just -9 in 2024.

Of note: The Weldon Cooper Center shows net in-migration over those same years, so the two sets of estimates are in conflict. However, if the more dire estimates from the Census Bureau are correct, they may at least be coming to an end. Both entities agree that Roanoke has more deaths than births; Weldon Cooper just says that’s the only reason for population decline, and the Census Bureau says it’s both deaths and people moving out.

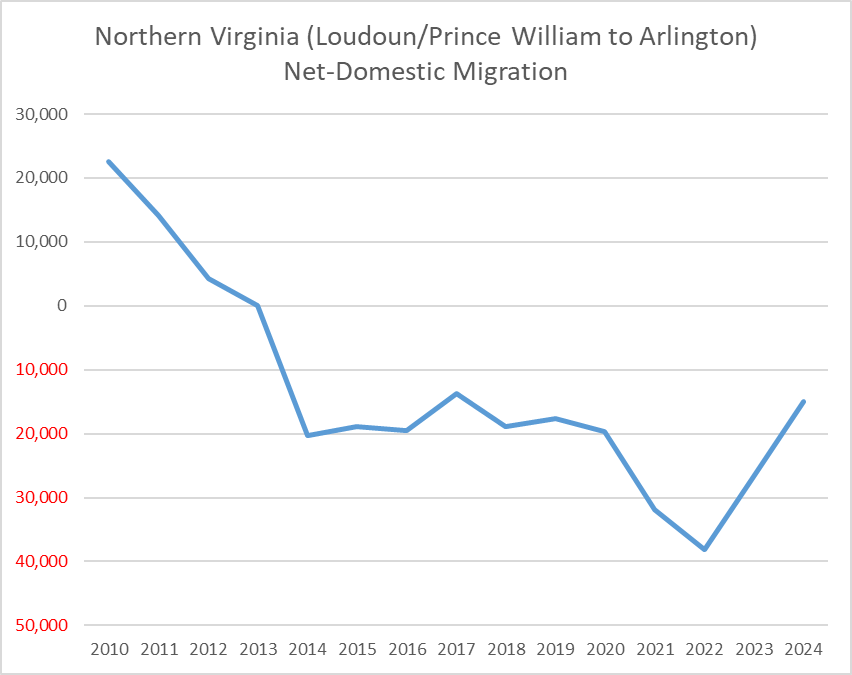

Out-migration from Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads is slowing down

Overall, one of the big population trends in Virginia has been that more people are moving out of the state’s two biggest metro areas than are moving in. Both the Census Bureau and Weldon Cooper agree on that.

Here’s an example of how those outflows are slowing down: The Census Bureau says that Fairfax County saw out-migration of -21,751 in 2022 and -13,847 in 2023, with “just” -8,323 in 2024. That’s still the equivalent of losing Scott County one year, losing Amelia County the next and then Mathews County last year. (Again, these numbers are just for domestic migration; we’ll delve deeper tomorrow.)

The Census Bureau says Virginia Beach has seen the same thing, with out-migration of -6,052 in 2022, -3,857 in 2023 and -2,284 last year.

While the “why” those people are leaving may be in dispute, the “where” is not. Many are moving out of state; we know this from Internal Revenue Service records. However, a growing number of people who are moving out of Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads are staying in Virginia and are moving instead to rural areas in-state. “Since 2020, Virginia has at least temporarily managed to divert more migration out of Northern Virginia to other parts of Virginia rather than out of state,” Lombard says. “IRS migration data points towards this as well with increased migration from Northern Virginia to the Richmond area and increased migration from the Richmond area to other parts of Virginia, including no doubt the Northern Neck.”

Separate data also shows that, over the past decade, Roanoke and Lynchburg have risen as preferred destinations for people moving out of the Washington metro area. I wrote a whole column on this last month.

That’s why I say that rural Virginia (and not just rural Virginia, since Roanoke and Lynchburg aren’t rural) is “saving” the state demographically. Without the net in-migration we’re now seeing broadly across rural Virginia, the state would be in a more challenging position, particularly as it grapples with the economic disruptions in Northern Virginia due to Trump’s government downsizing.

Coming tomorrow: Is Fairfax County gaining population or losing population? Here’s why two sets of population estimates differ and why the answer is a big deal for the entire state.

I write a weekly political newsletter, West of the Capital, that goes out Friday afternoons. You can sign up for any of our free newsletters below: