“I’m not good,” the man behind the wheel of the black Toyota Corolla repeatedly told Radford city police officer J.K. Caudell during a traffic stop last July.

Caudell found two empty vodka bottles under the passenger’s seat of the car and a mixed drink in the cupholder.

The man’s parents had called police after receiving texts from him saying he was planning on crashing his car.

Flock Safety cameras identified and located his vehicle based on information from the parents. Caudell pulled him over before he could harm himself or anyone else.

***

As part of its State of Surveillance project, Cardinal News asked law enforcement agencies to share how they have used license plate reading technology. We asked for the details behind apprehensions assisted by LPR tech. Reporters talked to police chiefs, sheriffs, commonwealth’s attorneys and a public defender, an anti-surveillance activist and a legislator.

Some police sent incident reports with information redacted. Others sent full, unredacted incident reports.

Some sent anecdotes describing cases in which the tech was used, but they would not provide corroborating documentation for a specific case. Some talked through such anecdotes over the phone.

Those stories included locating stolen vehicles and known suspects, apprehending a suspect in a breaking-and-entering and robbery case, and locating elderly persons reported missing.

The Halifax County Sheriff’s Office supplied Cardinal News with an audit of all Flock plate searches that went through their system for a 30-day period earlier this year. The audit provides insight into how the LPR search tool is used, but does not provide outcomes.

Augusta County, Boones Mill and Wise County responded, saying they could not list any examples of when their Flock technology has helped to solve a case.

The city of Lynchburg said that the technology was helpful, but did not provide any specifics or records.

The responses indicate the lack of any reporting standard when it comes to law enforcement explaining their use of public surveillance tech.

Still, even this piecemeal gathering starts to show how public surveillance is being used by police across Southwest and Southside Virginia.

***

When Daniel Nathan Janack was pulled over driving a homicide victim’s car in North Carolina, his legal troubles were just beginning. A wide-net search of thousands of Flock cameras had found the victim’s car hundreds of miles away in another state. After extradition to Virginia, Janack was charged in the death of a Pulaski man. His trial starts later this year.

Morgan Akers, the Freedom of Information Act officer for the Pulaski County Sheriff’s Office, noted that the LPR tech didn’t “solve” the case, but sped up Janack’s apprehension.

***

In Bristol, private video combined with public LPR tech to identify a suspect

Law enforcement agencies have evolved a way to enhance their existing public surveillance video when it comes to solving a crime: They’ve asked business owners and citizens for their store or home security video.

A string of front-door security videos might catch a glimpse of a vehicle passing by that can lead to a more detailed vehicle description in an LPR search, which can eventually lead to the plate number. Time and location data can be plotted to provide a more detailed view of the escape route of a wanted vehicle.

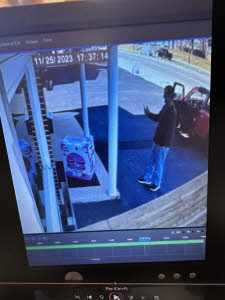

In November 2023, a cellphone was stolen at a gas station convenience store in Bristol.

The store’s private surveillance captured an image of the suspect’s vehicle. Unfortunately, the plate number wasn’t clear.

Using only a description of the vehicle, Bristol police ran a search through the Flock Safety network. When a vehicle matching that description was captured by a Flock camera, they were able to identify its plate number, leading to an arrest.

Bristol Police Sgt. Leonard Dorton calls the technology “a critical tool.” He remembers at least four cases in which it helped identify a suspect.

The same month the cellphone was stolen, Dorton said a delivered package was taken from a residence in Bristol. Again, a private camera, this time belonging to the resident, captured a photo of the vehicle, but again, no identification was visible — until a vehicle matching that description passed through a license plate reader.

Last September, a vehicle involved in a hit-and-run was identified using license plate readers. Also around that time, Dorton said license plate readers identified a stolen car as it drove past, which helped to pinpoint when the car was stolen.

He acknowledged that people can be wary of how much surveillance technology is used today.

“It’s a useful tool we’re able to utilize,” Dorton said. “It’s not used for any other purpose.”

***

In the still frame from a private video cam, the man stood a few feet away from the Minnie Mouse bumper car, delivered to someone’s porch and waiting for its new owner to unbox it, and appeared to take a photo of it.

Then he lifted the box and put it in his red car and drove off — maybe just enough information captured by the homeowner’s private video camera for police to query Flock and find some hits on red vehicles heading in that direction at that time of the day.

Except this one got away.

The man had in fact delivered the box, then decided to take it for himself and leave the state, according to Bristol police. The retailer refunded the buyer for the purchase; the buyer declined to press charges; the man was never arrested or charged. The Minnie Mouse bumper car was never recovered.

***

Public surveillance has its limits, even when combined with private security cameras owned by citizens and businesses.

What’s also missing from the study of public surveillance, besides whether there’s enough evidence to back up claims of it solving crimes and lowering certain crime rates, are the nuts-and-bolts details about exactly how it’s used on a daily basis by law enforcement.

Law enforcement agencies using Flock Safety can host their own Flock Transparency page. The Roanoke Police Department’s transparency page on Wednesday, May 21, shows that the agency’s 16 cameras had identified and photographed 293,455 vehicles in the past 30 days.

RPD initiated 605 searches using the Flock network in the same time period, an average of over 20 searches a day. The searchable data can go far beyond the cameras the Roanoke police have installed in the city.

The transparency page gives an overview of what that police department policy considers proper usage for Flock footage in its investigations. Roanoke also lists its prohibited uses: “Immigration enforcement, traffic enforcement, harassment or intimidation, usage based solely on a protected class (i.e., race, sex, religion), Personal use.”

Agencies can produce audits of their searches. The question is, what do those audits show? Cardinal News acquired one local agency’s 30-day audit in an effort to find out.

Auditing the audit

The Halifax County Sheriff’s Office makes strategic use of the search tool that connects thousands of law enforcement agencies and their public-facing Flock cameras. Or as Capt. Seth Bowen puts it: “We use the Flock system when we don’t have enough information.”

Bowen explains: “If somebody says, ‘I came home and found my home broken into, my neighbor said they saw a red F-150 with stickers in the back,’ that is enough information for us to put in the system.”

Bowen said that in such a scenario, Flock might be able to give 20 examples of cars that match that description, which would allow law enforcement to have the victim narrow the search.

The Halifax County Sheriff’s Office responded to Cardinal’s request for details about how it uses LPR tech, providing an audit of its Flock searches across March and part of April.

The audit offers an unprecedented look into how police use data searches of LPR cameras as part of their jobs.

Halifax deputies made 208 inquiries to the Flock database. A handful of officers represented the majority of those who made requests, including deputies Giles Jones, Thomas Moore and Bowen.

Around 5:49 a.m. on March 29, Moore searched the Halifax Flock network of two cameras for a “Virginia” vehicle three times in a minute.

Over a quarter of the total queries on the audit were searching a much wider network of 840 police agencies using a total of 13,924 public-facing cameras. Another dozen queries on the audit reached out to 926 agencies.

Because the agency could have redacted personal info like a license plate number from the version of the audit provided to Cardinal, those actions could reflect a couple of different approaches: Moore could have been searching for three unique vehicles over the same period of time, the last 24 hours. Or he could have been trying to track a single vehicle in real-time, and conducted the same search several times because he had confidence that the vehicle he was looking for would cross paths with one of Halifax’s cameras, perhaps on the way to work in the morning, or heading out of town, depending on the placement of those two cameras.

While Bowen spoke to Cardinal News, he did not make any other staff of the sheriff’s office available to talk about specific queries on the audit. We asked Bowen about one of the bigger searches.

“We only have two LPRs online at this time,” Bowen said.

Bowen says that a combination of searches could be part of a single investigation, such as a search for a stolen vehicle. Bowen said in one case a local search turned up nothing; since police did not know the direction of travel, they then performed the larger search “of all available devices.”

Most Flock transparency pages, including Roanoke’s, include a sentence to the effect of: “All system access requires a valid reason and is stored indefinitely.” On Halifax’s audit, the Reason column contains generic choices, nothing that approximates the probable cause that police would need to get a warrant. One “reason” is a sequence of digits. One reason is simply “Other.” That “Other” reason was chosen for 50 of the 207 searches:

- Larceny (80 searches)

- Other (50)

- Investigation (28)

- Stolen (22)

- Shots fired (9)

- Narcotics (8)

- Wanted (6)

- Suspicious vehicle (2)

- 25012857 (2)

Bowen said the decision to use the system isn’t arbitrary. If an investigation requires more information, Flock technologies might give officers information they otherwise wouldn’t have access to, like the color of a vehicle or the direction it was heading when captured on camera. Bowen said the license plate readers expand officers’ options.

“Ten minutes ago I used it to attempt to locate a vehicle on a wanted subject in another jurisdiction,” Bowen said. “They gave us very little information on the vehicle, the subject was in this area. They knew he was in this area. They gave us a vague vehicle description. I used what they gave me to try and search … for something that came through our area, in the past 24 hours, meeting that description.”

Bowen said the decision to use Flock or not is based largely on the amount of information available to them. In this regard, Flock becomes a way to fill in the proverbial blanks.

“If we don’t have enough information we’re going to use the resources that we have,” Bowen said. “Flock is one of those resources.”

In tech-loaded Martinsville, a prosecutor and public defender both entertain doubts, hopes

Among the communities making use of Flock surveillance technology, Martinsville was among the first to talk to Cardinal News about the new tech, while withholding any full-throated endorsement of its efficacy.

Last year, police Chief Mark Fincher oversaw the installation of dozens of license plate readers and gunshot listening devices. Fincher has described this period of time as a trial to gauge how useful they are to his department’s needs.

With dozens of pieces of functioning tech placed throughout the city, Flock’s presence is ubiquitous, even if its future is unknown. Beyond the tech and any arrests it may facilitate, the rest of the justice system awaits, with its courtrooms, judges and juries.

Commonwealth’s Attorney G. Andy Hall and Public Defender Sandra Haley have differing opinions on the technology.

Both have witnessed the evolution of law enforcement and the slow adoption of Flock-like technologies throughout the state.

“It’s been of some assistance to us,” said Hall, who said he believes the technology offered by Flock positively impacts public safety for communities that make use of it.

Haley said she believes the potential to exploit the technology is high. Specifically, she expressed concerns about privacy and data ownership.

“It’s very overbroad and very hit-or-miss, from one place to the next,” Haley said, referencing the disparate standards regulating surveillance technology from police department to police department.

The dueling opinions of the public defender and commonwealth’s attorney mirror the ongoing conversation about the technology.

While proponents maintain that the technologies can be useful, some, like Hall, acknowledge that departments should practice caution.

“You do have to be careful, in my estimation,” he said. “If you’re the police using such technology you have to be able to point to legitimate law enforcement reasons as to why you’re using it. I had a conversation about this the other day … if you run a license plate, if you run a criminal history, you better have a … legitimate law enforcement reason to have done so.”

“What would be useful is if we had some form of uniform adoption of standards where you wouldn’t have this patchwork series of rules, regulations and contracts,” Haley said.

While skeptical, Haley said she can imagine ways the technologies can be useful, if implemented properly.

“I suppose, one day, it’s going to be useful to somebody who is accused of a crime,” she said. “It can be used to establish an alibi, if we got a Flock screenshot of the client at the date and time a crime was alleged to have happened. That day has not come yet.”

Hall said that while there is room for compromise, he believes it will be some time before the courts, in Virginia and other states in which surveillance technology is a hot-button issue, establish precedent.

“It’s going to be a fluid situation and the courts are going to continue to look at it,” Hall said. “It’s not just readily identifiable information. I can go out to the parking lot and see 25 license plate numbers. I want the technology, when I look at those license plate numbers, to access the information a police officer can.”

Haley said she isn’t sure if there is a way to implement the technology in a way that doesn’t raise at least some concerns, but there is at least one best practice that departments can adhere to in order to foster goodwill among those who aren’t as trustful of the technology.

She believes that solution is in how departments handle the data.

“Not all law enforcement agencies have a transparency portal,” Haley said. “That’s where they keep the number of stops and the number of crimes solved by these things. I think the more available the data is and the less amount of time the data is stored that would alleviate, I think, some of the concerns.”

Walking towards a surveillance state

Brad Haywood is a criminal defense attorney with two decades of experience who started Justice Forward Virginia, an organization advocating for criminal justice reform in the commonwealth.

“It is Big Brother, that’s exactly what it is,” he said about Flock and its stated vision to end crime. “To me, that’s the cost. We’re just walking more towards a surveillance state where nobody has privacy.”

He said he can see Flock technology being helpful in cases of abduction or stolen vehicles, or locating someone who has a warrant out for their arrest. But he questions the effectiveness of the technology in solving serious crimes.

“If you have a license plate, I would think you probably know who did it,” he said. “You can find another way. It’s not like you’re cracking a case with a license plate reader.”

He also said there is so much technology already available to law enforcement, whether that be private surveillance technology or technology that officers are required to use.

Pulaski County Commonwealth’s Attorney Justin Griffith said he’s “caught off guard” by the amount of private surveillance there is now — from convenience store cameras to home Ring cameras.

But he said Flock specifically has been a “game changer” for Pulaski, not just for criminal investigations, but for missing adults, Amber alerts and welfare checks.

He said it’s one of the first things law enforcement looks at after doing eyewitness interviews, or even beforehand, to get a direction of where to take the interview.

“It provides more leads for cases than other technology has,” Griffith said. He added that the technology has increased the amount of collaboration between agencies and has become “an integral part of our daily operations.”

He said law enforcement has “no interest” in using Flock for any purposes besides what is listed above. “They should stay vigilant and make sure it’s not abused, and if it’s abused, that person that abused it should not have access and there should be consequences,” he said.

Haywood is supportive of further regulation on the tech. Meanwhile, a recently enacted law that takes effect July 1 will add regulation — while taking away public oversight or third-party guardrails to police’s use of the data.

Public surveillance is about to go out of the public’s reach

The new law will limit the use of LPR tech to investigations of a crime, investigations of missing persons or “a person associated with human trafficking,” or to receive notifications of endangered or missing persons, a person with an outstanding warrant, or a stolen vehicle or license plate.

It will set a limit of 21 days that law enforcement agencies and Flock can hold footage before deleting it, down from Flock’s standard 30 days.

Agencies will be required to publicly post their policies regarding LPR tech, as well as the annual report they submit to Virginia State Police. That report will include the total number of times the system was queried, including the specific purposes of the queries; the race, ethnicity, age and gender of the driver of any vehicle stopped as a result of a notification from the system; and the number of identified instances of unauthorized use of the system, among others.

As long as “Other” is a valid reason to query the system, finding unauthorized uses may be an exercise in futility for whoever is looking.

And that’s the tricky part of this new law.

Because if you’re the one looking for the original footage or audit, you’ll be out of luck after June 30, 2025. “System data and audit trail data shall not be subject to disclosure under the Virginia Freedom of Information Act.”

In other words, it leaves the policing of the system to the police.

Meanwhile, while local law enforcement agencies can state in their policies that they will not use Flock footage for immigration enforcement, they apparently can’t control other law enforcement agencies from using their shared footage for that purpose. A 404 Media story examined network audits collected via Freedom of Information Act from the Danville, Illinois, police and documented other law enforcement agencies’ searches of Danville data with reasons such as “ICE,” “illegal immigration” and other related terms.

Local law enforcement agencies may maintain strict policies for LPR usage that reflect the wishes of their community. The data’s use by other agencies may not have been contemplated deeply by such agencies. How localities may wish to control this use of their legal property is still to be determined.